-

全球气候变化带来的一系列生态、经济、社会问题日益严重,引发了国际社会的高度重视。导致全球气候变暖的重要原因是二氧化碳(CO2)年排放量不断增加。目前除工业减排CO2外,植物固碳已成为解决这一问题的重要途径[1]。陆地碳汇是全球碳循环的基础,并正在被用来抵消人为CO2排放量的增加,其中森林生态系统作为陆地生态系统中最大的碳库,存储着整个陆地生态系统80%的地上碳和70%的土壤碳[2−3]。植硅体是植物根系吸收土壤溶液中的单硅酸[Si(OH)4],在蒸腾拉力的作用下沉积于细胞壁、细胞腔或细胞间隙内的非晶质二氧化硅颗粒物[4-6]。植硅体形成过程中会包裹一定量的有机碳,称为植硅体封存有机碳(phytolith-occluded organic carbon, PhytOC)[7−8],这部分被包裹的有机碳由于受到植硅体的保护而具有耐高温和高度抗氧化等特性,如果没有大的地质变迁,便能够在土壤以及沉积物中保存长达数千年甚至数万年之久,从而成为陆地土壤的长期固碳机制之一[9-11]。因此,植硅体封存的有机碳在减少大气CO2含量、缓解温室效应等方面具有重要的意义[12−14]。已有研究主要集中于植硅体碳含量较高的富硅植物,例如水稻Oryza sativa[15]、黍Panicum miliaceum、粟Setaria italica[9]、小麦Triticum aestivum[2]、甘蔗Saccharum officinarum[3]等农作物、草地和湿地植物[16-17]、竹类[18-20]。马尾松Pinus massoniana是分布面积较广的一种森林类型,也是中国松科Pinaceae植物中用途最广的先锋树种。近年来,有学者研究发现:马尾松生态系统有着可观的植硅体碳储量,其叶片中植硅体封存有机碳含量高于同为针叶林的杉木Cunninghamia lanceolata甚至高于禾本科Poaceae植物[21-22]。植物生物量对植硅体碳储量也有着很大的影响[20, 23]。张振等[24]研究发现:马尾松树干生物量占到总生物量的77.2%,由此可知马尾松树干植硅体碳汇潜力不可忽视。同一植物不同器官植硅体封存有机碳含量不同[25],同一树种不同种源由于适应性和生理生态差异,植硅体封存有机碳储量也会产生差异。关于马尾松不同种源植硅体碳汇差异的研究鲜见报道,本研究对来自全国的20个马尾松种源树干进行采样分析,研究不同马尾松种源树干植硅体碳储量的差异,并聚类分析,筛选出马尾松树干植硅体碳封存潜力较强的种源,为中国马尾松林生态系统植硅体碳封存研究提供依据。

HTML

-

研究区位于浙江省淳安县千岛湖东南湖区的姥山林场马尾松种源试验林(29°33′30″N,119°02′55″E),地处中亚热带地区,雨量充沛,四季分明,年平均气温为17.0 ℃,≥10 ℃的年积温为 5 410 ℃,年平均日照时数1 951 h,年降水量1 430 mm,无霜期263 d。姥山林场设置的试验地海拔150 m,坡度20°~30°,土壤为红壤土类的黄红壤亚类,土壤厚度80 cm以上,土壤有机质15.80 g·kg−1,碱解氮53.50 mg·kg−1,速效钾18.50 mg·kg−1,有效磷0.99 mg·kg−1,交换性钙128.00 mg·kg−1,交换性镁9.24 mg·kg−1。

-

1984年春,在姥山林场栽植了来自14个省区的49个马尾松种源1年生裸根苗,采用双列小区完全随机排列,重复8次(8株),株行距2 m×2 m,管理措施一致,用以筛选速生、优质的马尾松种源[26]。2017年12月对保存完好的20个马尾松种源植株进行调查、采样,通过每木测定,得到每个种源的平均木,随机选取3个小区,每个种源选取胸径与平均木相近的3株植株作为标准株,人工摘取标准株新鲜叶片于样品袋中,新鲜叶片带回实验室后用去离子水洗净,105 ℃杀青25 min,75 ℃下烘干48 h,再磨碎后于塑封袋保存。至2018年4月,再次砍伐20个种源胸径与平均木相近的3株标准株对马尾松进行树干取样,取得的树干圆盘带回实验室进行烘干磨碎处理,分析测定。

-

所有植物样品的碳和氮采用Elementar Vario MAX CN碳氮元素分析仪测定;植物植硅体的提取采用微波消解法[27],为了大量提取植硅体而在此方法上有所改进,用浓硝酸和双氧水大量消煮前处理,再进行微波消解;而植硅体封存有机碳的测定同植物碳和氮的测定方法。土壤有机质采用重铬酸钾外加热法测定;碱解氮采用碱解法测定;有效磷采用Bray法测定;速效钾采用乙酸铵浸提,火焰光度法测定;交换性钙、镁采用EDTA滴定法测定[28]。

-

w植硅体=m植硅体/m样品,其中:w植硅体为植硅体质量分数(g·kg−1),m植硅体为植硅体质量(g),m样品为样品干质量(kg)。w有机碳=m有机碳/m植硅体,其中:w有机碳为植硅体封存有机碳质量分数(g·kg−1),m有机碳为植硅体有机碳质量(g),m植硅体为植硅体质量(kg)。所以,w植硅体碳=m有机碳/m样品,其中:w植硅体碳为植硅体碳质量分数(g·kg−1)。C植硅体碳=B树干×w植硅体碳,其中:C植硅体碳为标准株树干植硅体碳储量(g·株−1),B树干为树干生物量(kg·株−1)。3次重复,取平均值。数据处理用SPSS 18.0完成,用Duncan新复极差法检验不同处理的差异显著性,并用植硅体质量分数、植硅体封存有机碳质量分数等碳储指标对所有参试种源进行Q型聚类分析。

1.1. 研究区域概况

1.2. 实验设计

1.3. 样品分析

1.4. 数据的计算和统计

-

表1显示:20个马尾松种源树干的总有机碳质量分数无显著差异,其变化范围为467.6~489.6 g·kg−1,而在不同种源中树干植硅体质量分数存在显著差异,表现为安徽太平32(0.845 g·kg−1)、贵州黄平122(0.702 g·kg−1)显著高于湖北通山84(0.465 g·kg−1)(P<0.05),而后者又显著高于广东乳源102(0.305 g·kg−1)(P<0.05)。不同马尾松种源树干植硅体封存有机碳质量分数的变化范围为126.8~210.2 g·kg−1,存在显著差异(P<0.05),树干植硅体封存有机碳质量分数以江西吉安63(210.2 g·kg−1)最高,显著高于福建邵武91(172.4 g·kg−1)(P<0.05),后者又显著高于浙江庆元54(126.8 g·kg−1)(P<0.05)。20个马尾松种源树干植硅体碳质量分数变化范围为0.049~0.128 g·kg−1,也存在显著差异(P<0.05)。树干植硅体碳质量分数以安徽太平32(0.128 g·kg−1)最高,显著高于贵州黎平124(0.076 g·kg−1)(P<0.05),后者又显著高于广东乳源102(0.049 g·kg−1)(P<0.05)。

种源号 总有机碳/(g·kg−1) 植硅体/(g·kg−1) 植硅体封存有机碳/(g·kg−1) 植硅体碳/(g·kg−1) 河南桐柏21 489.6±22.6 a 0.421±0.049 cdef 188.9±16.8 abc 0.073±0.020 cdef 安徽太平32 485.9±5.4 a 0.845±0.033 a 148.0±15.9 de 0.128±0.008 a 安徽屯溪33 478.5±13.9 a 0.368±0.075 def 167.5±16.8 cd 0.059±0.013 def 浙江庆元54 484.0±14.3 a 0.519±0.057 c 126.8±11.8 e 0.070±0.016 cdef 浙江淳安56 474.1±9.9 a 0.437±0.062 cdef 148.4±14.2 de 0.064±0.004 def 江西吉安63 483.5±14.5 a 0.380±0.094 cdef 210.2±26.7 a 0.070±0.009 cdef 湖南安化72 488.7±4.8 a 0.330±0.026 ef 177.2±21.6 abcd 0.058±0.006 def 湖南资兴74 478.3±10.8 a 0.405±0.075 cdef 167.2±24.7 cd 0.066±0.003 def 湖北远安81 477.5±14.0 a 0.388±0.079 cdef 183.4±16.4 abcd 0.067±0.006 cdef 湖北通山84 475.5±3.4 a 0.465±0.119 cde 204.5±11.8 ab 0.091±0.026 bc 福建邵武91 475.8±13.6 a 0.410±0.082 cdef 172.4±10.0 bcd 0.069±0.021 cdef 福建永定95 467.6±8.2 a 0.395±0.094 cdef 147.6±22.1 de 0.051±0.002 ef 广东乳源102 479.9±10.9 a 0.305±0.074 f 162.2±18.3 cd 0.049±0.013 f 广东信宜105 476.5±10.2 a 0.481±0.069 cd 194.1±19.3 abc 0.111±0.024 ab 广西恭城111 474.7±10.5 a 0.396±0.036 cdef 205.1±15.5 ab 0.081±0.008 cd 广西岑溪115 472.9±5.0 a 0.519±0.033 c 205.7±5.5 ab 0.107±0.010 ab 贵州黄平122 476.5±11.6 a 0.702±0.103 b 187.6±33.7 abc 0.121±0.009 a 贵州都匀123 476.6±8.2 a 0.364±0.002 def 148.5±5.5 de 0.054±0.002 ef 贵州黎平124 469.1±2.8 a 0.465±0.119 cde 187.0±27.6 abc 0.076±0.001 cde 四川南江131 477.1±12.9 a 0.335±0.043 ef 190.3±19.2 abc 0.059±0.010 def 说明:表内的数据为平均值±标准差;同列不同字母表示不同种源间差异显著(P<0.05) Table 1. Comparison of the contents of total organic carbon(TOC), phytoliths, OC in phytoliths, and phytolith in dry matter in trunk of masson pine from different provenances

-

表2可知:20个马尾松种源平均胸径和株高变化范围为分别17.1~32.3 cm和16.3~19.5 m。马尾松标准株树干生物量最高的是广西岑溪115(295.39 kg·株−1),最低为河南桐柏21(76.48 kg·株−1);马尾松标准株树干植硅体碳储量最高的是广西岑溪115(31.58 g·株−1),最低的是湖南安化72(4.83 g·株−1),前者是后者的6.54倍。

种源号 胸径/

cm株高/

m树干生物量/

(kg·株−1)标准株植硅体

碳储量/(g·株−1)河南桐柏21 17.1 17.0 76.48 5.61 安徽太平32 21.8 17.0 124.85 16.03 安徽屯溪33 22.5 19.0 143.76 8.54 浙江庆元54 26.1 19.1 195.11 13.64 浙江淳安56 21.1 18.3 122.59 7.88 江西吉安63 20.8 17.4 114.65 8.08 湖南安化72 18.0 16.5 82.77 4.83 湖南资兴74 26.7 18.2 197.10 13.01 湖北远安81 21.5 18.8 129.52 8.70 湖北通山84 22.5 18.5 141.33 12.93 福建邵武91 27.2 19.2 212.87 14.60 福建永定95 28.4 18.9 229.44 11.79 广东乳源102 28.8 19.5 241.78 11.94 广东信宜105 25.1 19.3 182.05 20.23 广西恭城111 29.3 19.3 247.94 20.08 广西岑溪115 32.3 18.6 295.39 31.58 贵州黄平122 22.3 18.4 137.86 16.68 贵州都匀123 19.6 17.2 100.83 5.45 贵州黎平124 24.1 19.0 164.73 12.55 四川南江131 20.2 16.3 103.33 6.12 说明:树干生物量根据模型计算得到[29] Table 2. Comparison of PhytOC stock in trunk of masson pine plant from different provenances

-

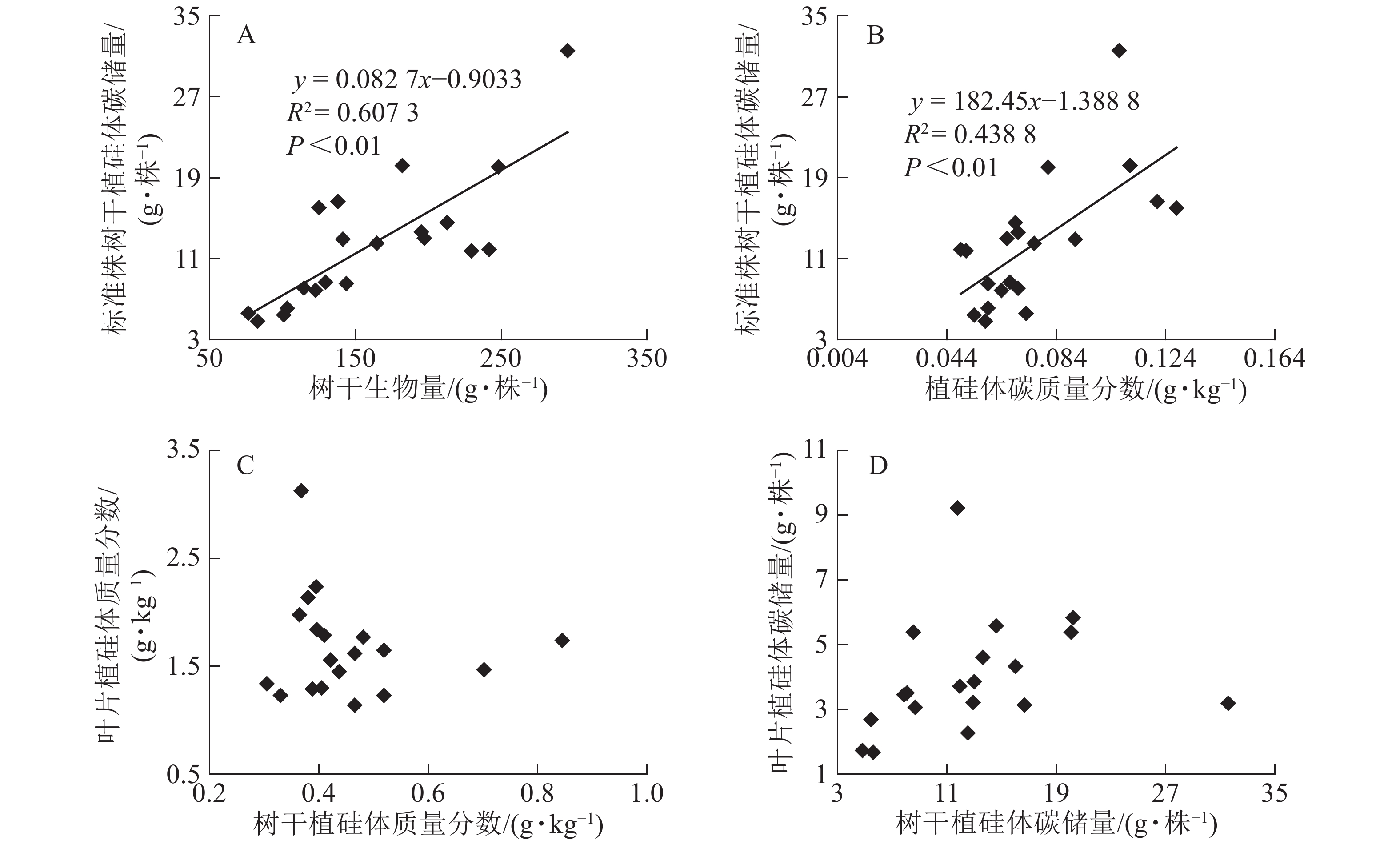

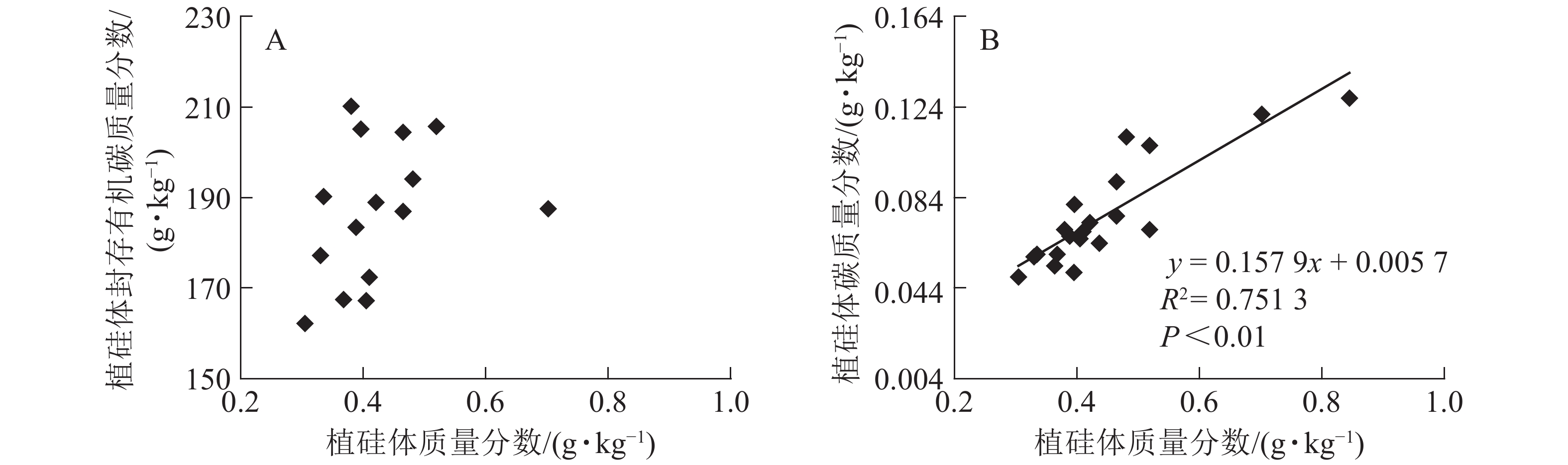

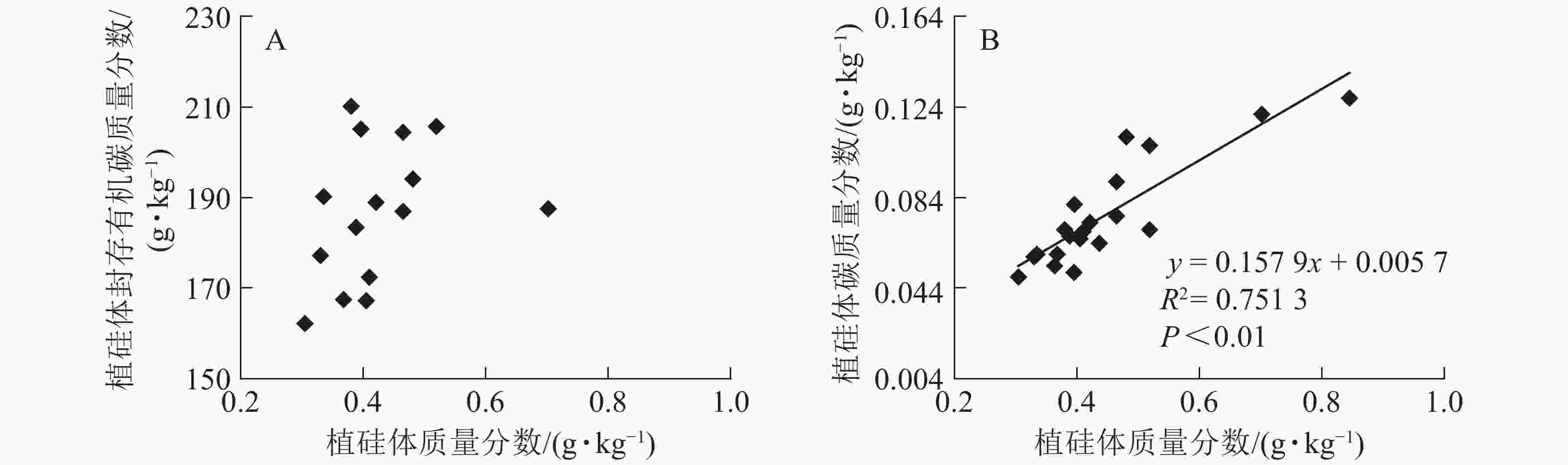

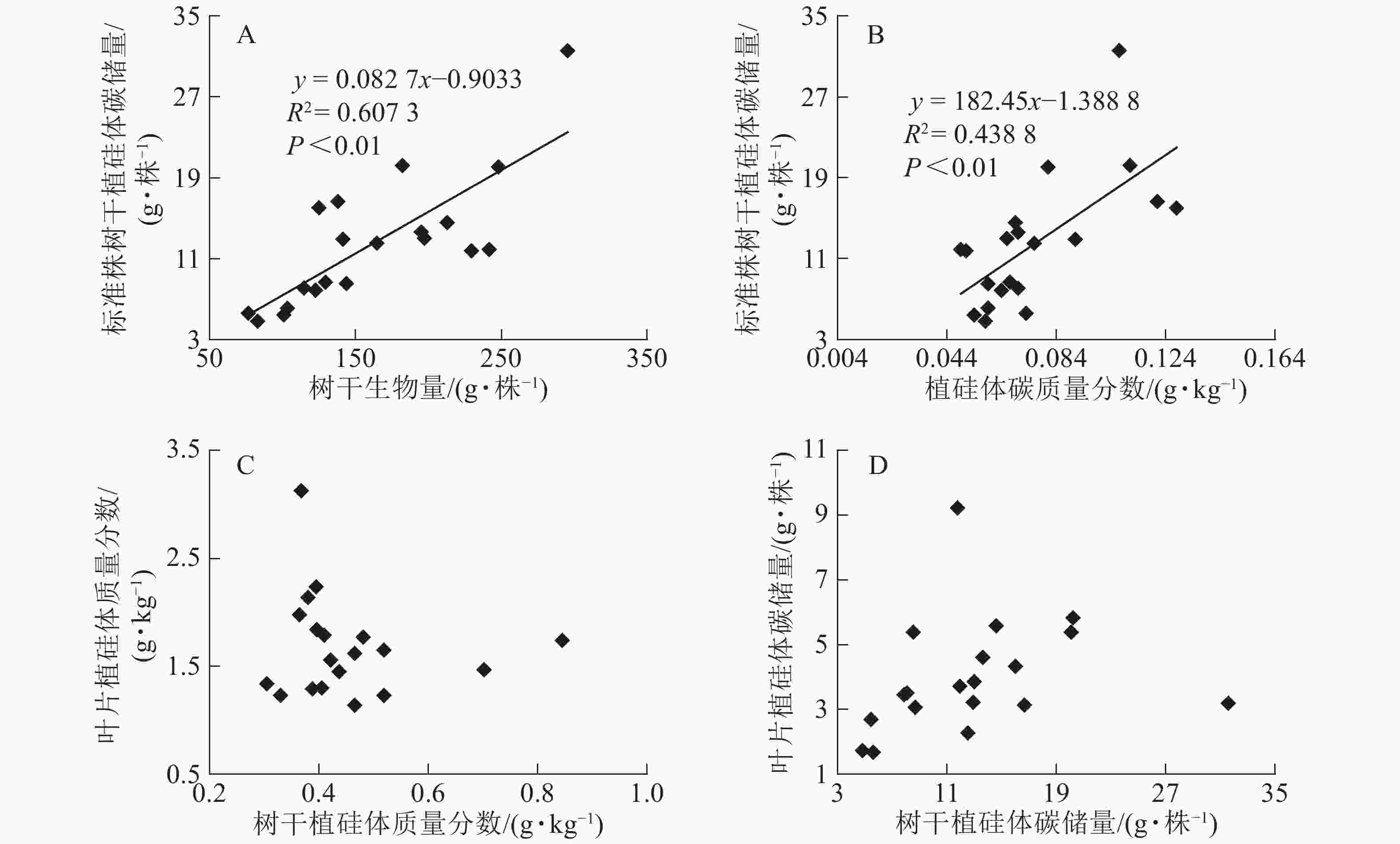

图1相关性分析发现:不同马尾松种源树干植硅体质量分数与植硅体封存有机碳质量分数无相关关系,而植硅体质量分数与植硅体碳质量分数呈极显著的正相(R2=0.751 3,P<0.01)。20个马尾松种源的标准株树干植硅体碳储量与其树干生物量(R2=0.607 3,P<0.01)或树干植硅体碳质量分数(R2=0.438 8,P<0.01)之间均呈极显著正相关,而马尾松标准株的叶片与树干植硅体质量分数、植硅体碳储量无相关关系(图2)。

-

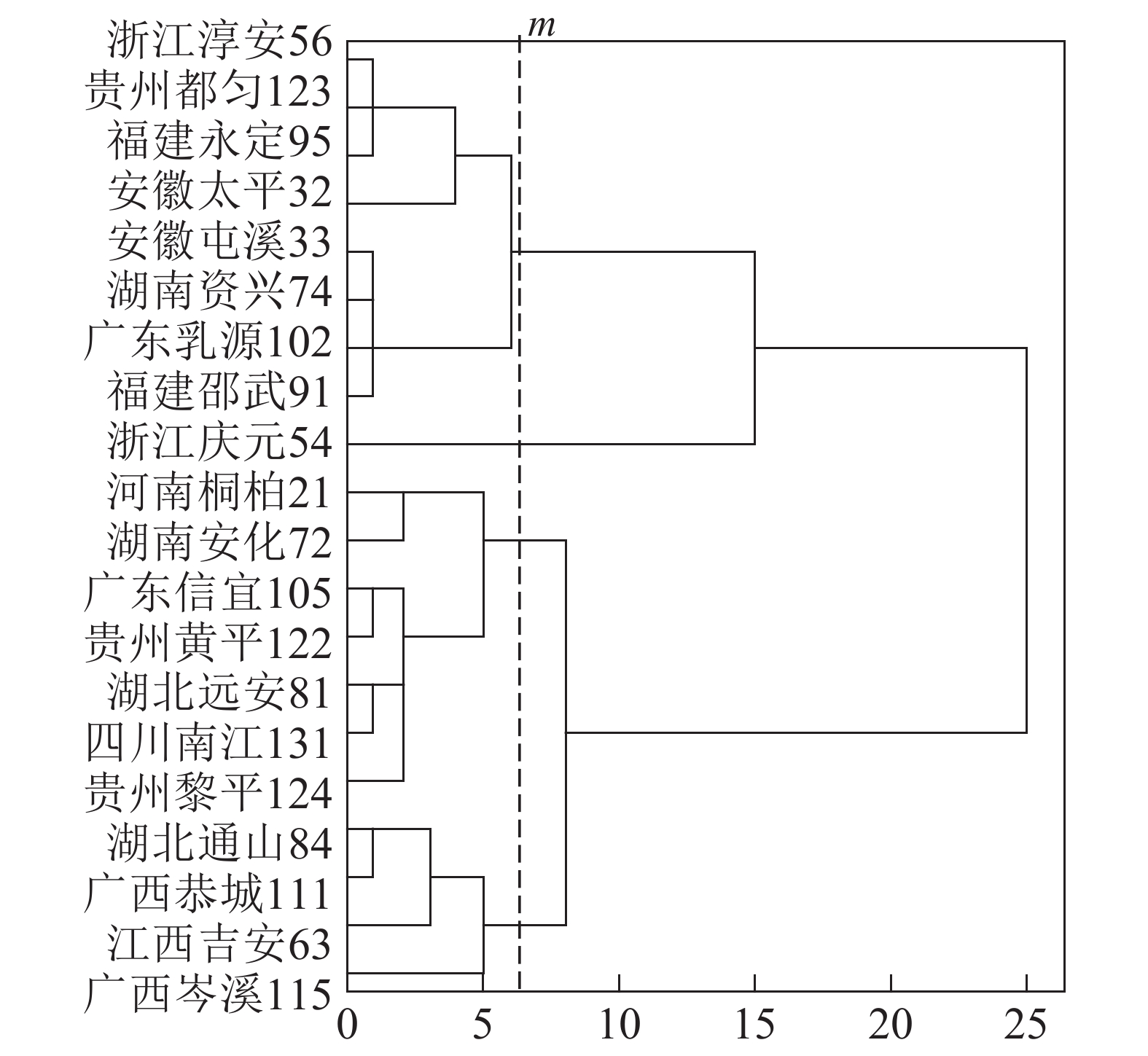

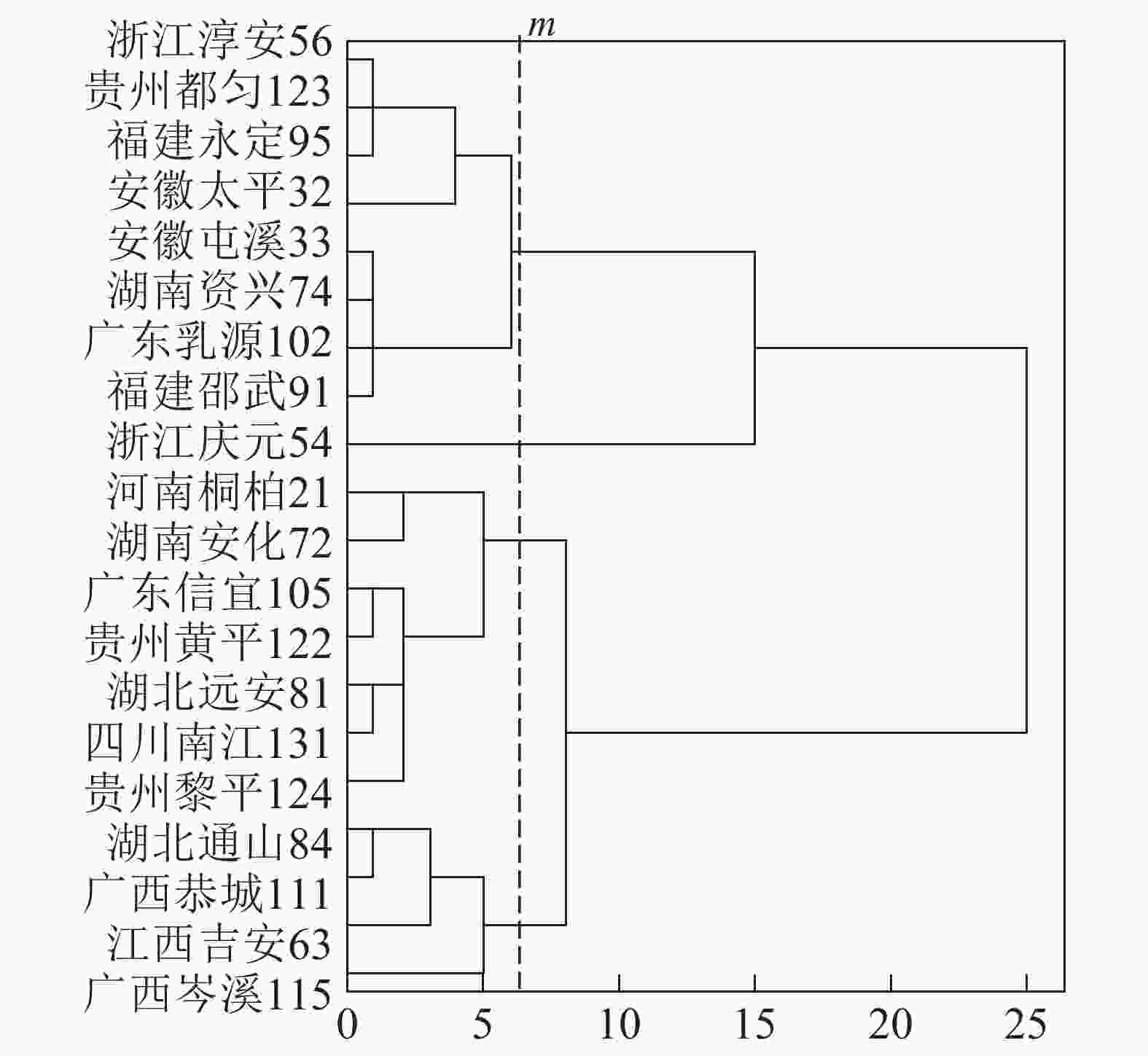

基于上述结果,利用马尾松总有机碳质量分数、树干植硅体质量分数、植硅体封存有机碳质量分数等指标的均值对20个马尾松种源进行Q聚类分析(图3)。以图中m线为阈值可以将20个种源划分为4类,第1类为湖北通山84、广西恭城111、江西吉安63以及广西岑溪115,此类马尾松种源总有机碳质量分数为472.9~483.5 g·kg−1,植硅体封存有机碳质量分数最高,为204.5~210.2 g·kg−1,植硅体碳质量分数也整体相对较高,为0.070~0.107 g·kg−1,标准株马尾松树干植硅体碳储量为8.08~31.58 g·株−1,其中广西岑溪115(31.58 g·株−1)标准株树干植硅体碳储量最高;第2类马尾松种源包括河南桐柏21、湖南安化72、广东信宜105等7个种源,此类马尾松种源总有机碳质量分数为469.1~489.6 g·kg−1,树干植硅体封存有机碳质量分数为177.2~194.1 g·kg−1,植硅体碳质量分数为0.058~0.121 g·kg−1,标准株马尾松树干植硅体碳储量为4.83~20.23 g·株−1;第3类为浙江淳安56、贵州都匀123、福建永定95、安徽太平32等8个种源,这类马尾松种源总有机碳质量分数为467.6~485.9 g·kg−1,树干植硅体封存有机碳质量分数为147.6~172.4 g·kg−1,植硅体碳质量分数为0.049~0.128 g·kg−1,标准株树干植硅体碳储量变动为5.45~16.03 g·株−1;浙江庆元54为第4类马尾松种源,树干植硅体碳封存能力最差,总有机碳质量分数为484.0 g·kg−1,植硅体封存有机碳质量分数为126.8 g·kg−1,植硅体碳质量分数为0.070 g·kg−1,标准株树干植硅体碳储量为13.64 g·株−1。

2.1. 不同马尾松种源树干总有机碳、植硅体、植硅体封存有机碳以及植硅体碳质量分数的比较

2.2. 不同马尾松种源单株树干植硅体碳储量的比较

2.3. 不同马尾松种源碳储指标相关性分析

2.4. 不同马尾松种源划分和优良种源选择

-

植硅体的形成与植物富集硅的能力有关,因此关于植硅体的研究大多集中于高富集硅植物叶片(禾本科)以及林下土壤中;植硅体的形成还与植物体自身蒸腾作用有关,而植物蒸腾作用主要发生在植物叶片表面[6,30-31],对地上部分其他器官的植硅体碳汇研究相对较少。以马尾松(非禾本科)为代表的针叶林,自身植硅体的形成受到叶片(针叶)蒸腾作用和植物自身富硅能力的限制,植物植硅体质量分数相对较少。

分析发现:马尾松树干植硅体质量分数与植硅体封存有机碳质量分数之间无相关性,与前人研究结果一致[2, 9, 20, 32],说明植硅体封存有机碳质量分数并不是由植硅体质量分数决定的,而可能与植硅体自身固碳能力和固碳效率有关;马尾松树干的植硅体质量分数和植硅体碳质量分数呈极显著的正相关(R2=0.751 3,P<0.01),这与中国亚热带重要树种植硅体碳研究结果[21]和苦竹Pleioblastus amarus林碳汇的研究结果[25]一致。植硅体碳质量分数还受到其他多种因素的影响,SONG等[23]对不同森林类型植硅体碳封存研究发现:植物植硅体碳质量分数与硅质量分数存在相关性;LI等[33]研究发现:植物植硅体碳质量分数还与植物吸收利用二氧化碳的速率相关。

-

标准株马尾松树干植硅体碳储量是由树干生物量和植硅体碳质量分数相乘得到的,20个马尾松种源的标准株树干植硅体碳储量与其树干生物量(R2=0.607 3,P<0.01)或植硅体碳质量分数(R2=0.438 8,P<0.01)之间均存在极显著正相关,说明标准株马尾松树干植硅体碳储量在一定程度上有随自身树干生物量和植硅体碳质量分数的增加而呈增加的趋势。而马尾松标准株的叶片与树干植硅体质量分数、植硅体碳储量无相关关系,这可能是植硅体自身固碳能力和固碳效率不同导致的。

本研究20个马尾松种源叶片植硅体碳质量分数范围为0.165~0.520 g·kg−1,明显高于马尾松树干植硅体碳质量分数(0.049~0.128 g·kg−1),叶片生物量范围为7.53~18.90 kg·株−1,树干生物量范围为76.48~295.39 kg·株−1,计算结果显示标准株叶片植硅体碳储量范围为1.67~9.22 g·株−1,标准株树干植硅体碳储量范围为4.83~31.58 g·株−1,可见树干巨大的生物量对植硅体碳储量的影响较大。

-

植硅体碳储量是评价植物生态系统现存植硅体碳封存潜力的一个重要指标,其大小不仅与植物种类有关,而且还与植物的种源有关。5种林分的凋落物植硅体碳储量比较发现:最大的毛竹Phyllostachys edulis林植硅体碳储量是最小的杉木林植硅体碳储量的6.8倍[34];8种散生竹地上部分植硅体碳储量研究发现:不同竹种间差异显著,最大的淡竹Phyllostachys glauca植硅体碳储量是最小的高节竹Phyllostachys prominens植硅体碳储量的10.8倍[35];本研究马尾松标准株树干植硅体碳储量最高的是广西岑溪115,最低的是湖南安化72,前者是后者的6.5倍。上述结果说明:植硅体碳储量在不同树种和种源之间存在着巨大差异,因而对同一种源森林生态系统来说,有可能通过选择高植硅体碳储量的林木来大大增加其植硅体碳的封存量。

3.1. 马尾松树干的植硅体、植硅体封存有机碳与植硅体碳质量分数

3.2. 马尾松生态系统植硅体碳储量的影响因素

3.3. 植硅体碳储量的不同树种和种源之间的差异

-

20个马尾松种源树干的植硅体质量分数、植硅体封存有机碳质量分数以及植硅体碳质量分数都有着显著的差异(P<0.05),其中树干植硅体质量分数最高的是安徽太平32(0.845 g·kg−1),最低的是广东乳源102(0.305 g·kg-1);树干植硅体封存有机碳质量分数最高的是江西吉安63(210.2 g·kg−1),最低的是浙江庆元54(126.8 g·kg−1);而植硅体碳质量分数最高的是安徽太平32(0.128 g·kg−1),最低的是广东乳源(0.049 g·kg−1)。由于生物量的差异,标准株树干植硅体碳储量最高的是广西岑溪115(31.58 g·株−1)。综合聚类分析,湖北通山84、广西恭城111、江西吉安63以及广西岑溪115为植硅体碳汇能力较强的种源,浙江庆元54植硅体碳汇能力最差。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: