-

植物挥发性有机化合物(VOCs)是植物体通过次生代谢途径合成的低沸点、小分子一类化合物[1],在植物与环境因子、微生物和动物互作中起着重要作用[2],特别对改善空气质量和提高人类身体健康有积极意义[3]。植物在生长过程中,会产生大量的空气负离子。植物进行光合作用利用二氧化碳(CO2)产生氧气(O2)过程中会形成空气负离子[4];树叶和树木尖端放电也能产生空气负离子,针叶树比阔叶树更容易产生负离子[5]。空气负离子既能降低PM2.5浓度,也能有效抑制细菌和真菌的生长[6];同时也是治疗多种慢性疾病的良药[7],不仅可以缓解人体心血管的舒张压和提高内分泌的稳定性,还能有效降低情绪和血清素含量[8]。FATEMI等[9]在研究植物VOCs对猕猴桃Actinidia chinensis防腐作用时发现:黑香芹Petroselinum crispum和茴香Foeniculum vulgare精油能够完全抑制猕猴桃果实灰霉病Botrytis cinerea的生长;ZHENG等[10]研究发现:反式肉桂醛对水稻Oryza sativa稻曲病病菌Ustilaginoidea virens感染具有较强的抑制作用。受害植物经(E)-2-己烯醛和(Z)-3-乙酸己酯处理后能释放更多的萜烯类化合物[11];萜烯类物质不仅具有增强植物的抗病能力[12],还能够抑制真菌生长[13]。同时萜烯类化合物具有重要的药用价值,如紫杉醇具有抗肿瘤效果,青蒿素具有抗疟疾特效[14]。植物释放的挥发物不仅是天然的“防腐剂”“保健品”,也是天然的空气“清洁剂”。林富平等[15]研究金桂Osmanthus fragrans ‘Thunbergii’挥发物对空气微生物的作用时发现:金桂对空气中细菌、真菌和放线菌具有较强的抑制作用;谢慧玲等[16]研究发现:皂荚Gleditsia sinensis和五角枫Acer truncatum等8种植物挥发物单体对细菌和放线菌有明显的抑制效果。目前,已有研究者在植物VOCs的抑菌活性[17]和林分空气负离子[18]的研究等方面取得了较大进展。但关于杨梅Myrica rubra、青梅Vatica mangachapoi、茶Camellia sinensis植物VOCs对环境的研究尚未见报道。本研究以杨梅、青梅和茶为对象,测定了3种植物VOCs组分和含量、园内空气负离子和微生物含量,探讨植物VOCs的抑菌和净化空气作用,为选择良好的经济林环境提供理论依据。

HTML

-

样地设在杭州市临安区浙江农林大学东湖校区杨梅园、青梅园和茶园(纯园无其他树种)教学实习基地(30°15′25″N,119°43′39″E),该研究区属中亚热带季风气候,温暖湿润,四季分明,雨热同期,有梅雨季节,空气湿润,年日照时数为1 939.0 h。年均气温为16.4 ℃,1月最低,平均为−0.4~5.5 ℃,极端最低为−13.1 ℃;7月最高,平均为24.4~30.8 ℃,极端最高为41.2 ℃。全年降水量为1 628.6 mm,年平均相对湿度在70%以上。空旷地为园外环境(无树木的影响);杨梅树高约6.0 m,胸径15.0 cm;青梅树高约5.0 m,胸径10.0 cm;茶树长势均匀,高约0.5 m。无病虫害,树木生长健康。2018年5月选择晴朗无风的天气,气温约30 ℃的条件下开展实验。

-

采用QC-2型大气采样仪(北京市劳动保护科学研究所),在距地面1.5 m(人正常呼吸的平均身高)处,对空旷地(对照)、杨梅、青梅、茶的树木VOCs以及园内空气VOCs进行采集,采集时间为9:00−11:00。气体循环流量为100 mL·min−1,采气时间为1 h,采样重复5次,采集后采摘3种树木叶片称量。3种树木及空气VOCs分析参照GAO等[19]的方法,采用动态顶空气体循环热脱附/气相色谱/质谱联用分析技术(TDS-GC-MS)。通过TDS-GC-MS技术分析,获得VOCs的总离子流量色谱图,利用NIST2008谱库查询,色谱峰面积进行定量分析,并计算相对含量。

-

采用ITC-201A 型(Andes公司生产,日本)空气负离子测定仪,在高度为1.5 m处测定空旷地(对照)、杨梅、青梅和茶园内的空气负离子数。选择5个采样点,采样点的距离为2棵树之间距离取平均值,采样时间为7:00、10:00、13:00、16:00和19:00。

-

按照周德庆[20]的方法配制细菌培养基(牛肉膏蛋白胨培养基)、真菌培养基(马丁式培养基)和放线菌培养基(高式1号培养基)。按照GAO等[19]方法分别配制了体积分数为0.1%、0.5%、1.0% 的罗勒烯、柠檬烯、壬醛和癸醛4种单体的培养基。

-

采用自然沉降法[16],在空旷地(对照)、杨梅、青梅和茶园内均设5个采样点,采集微生物。将3种不同培养基的培养皿分别置于离地面1.5 m高的平板支架上,距树干水平距离1.0 m,采集空气中自然漂浮的微生物(细菌、真菌和放线菌)。采样时间为7:00、10:00、13:00、16:00和19:00,培养基在空气中暴露10 min后,用保鲜膜包好后带回实验室置于25 ℃恒温培养箱中培养。接菌的培养皿在25 ℃培养箱培养24 h后进行细菌菌落统计,培养72 h后进行真菌菌落统计,培养96 h后进行放线菌菌落统计。根据微生物计算公式处理微生物数[15],计算公式为:菌数(个·m−3)=50 000N/(AT)。其中:N为培养皿中菌落平均数(个);A为培养皿的面积(cm2);T为打开培养皿皿盖的时间(min)。抑菌率=(对照菌数−处理菌数)/对照菌数×100%。

-

所有数据均为5次重复的平均值±标准差,利用Origin 9.0进行统计分析和作图。统计方法采用One-Way ANOVA,进行Tukey多重比较(P<0.05)。

1.1. 样地和供试树种

1.2. 研究方法

1.2.1. VOCs的采集分析

1.2.2. 空气负离子测定

1.2.3. 培养基的制备

1.2.4. 微生物采集

1.3. 数据处理

-

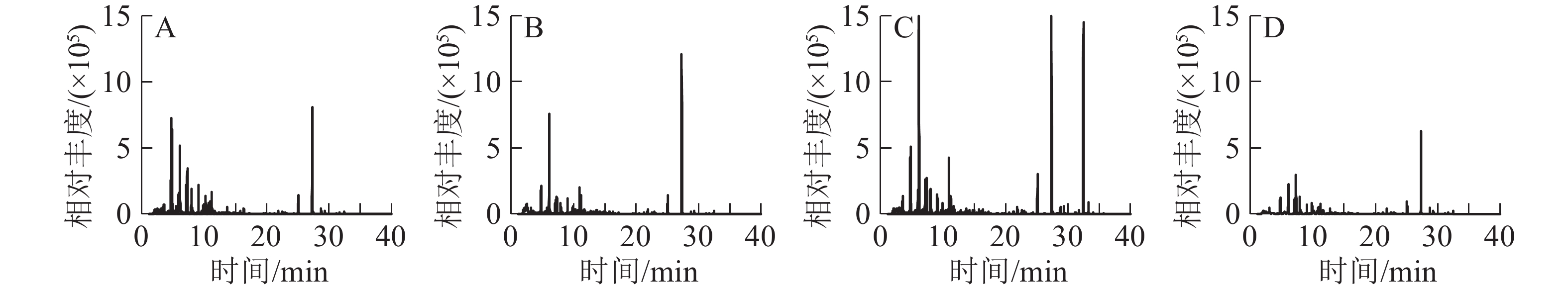

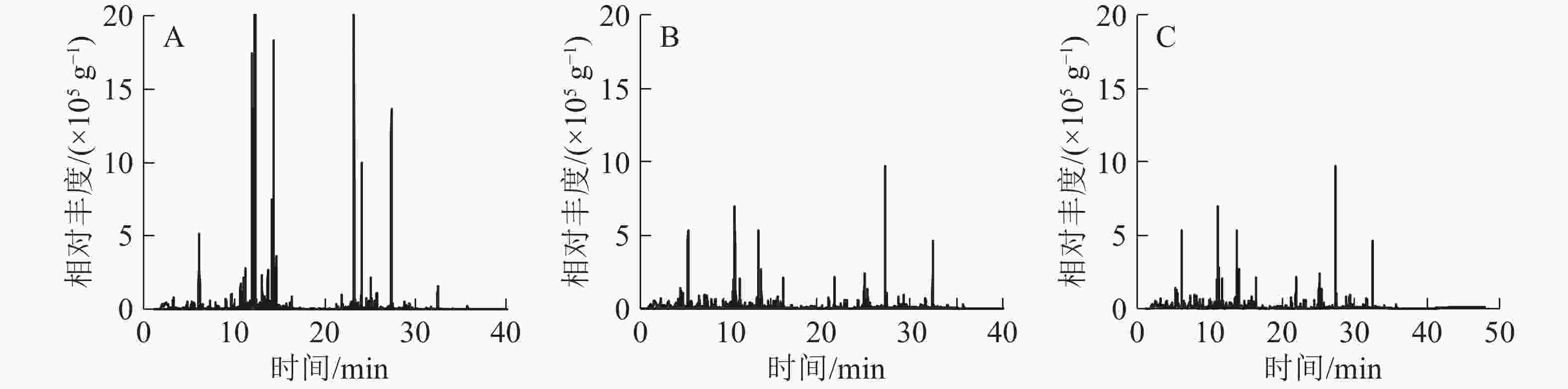

3种常绿树VOCs总离子流图共有41种化合物(图1和表1),主要有萜烯类、酯类、醛类、醇类、酮类和苯类。杨梅检测到22种化合物,其中:萜类有15种,占总量的78.5%,主要有α-草烯、香芹醇、罗勒烯、柠檬烯、石竹烯;4种醇类占总量的19.7%;1种醛类占总量的1.2%。青梅共检测到17种化合物,其中:3种酯类占总量的54.1%,主要有乙酸叶醇酯、丁酸辛酯;萜烯类有5种,占总量的11.1%;4种醛类占总量的12.9%;2种醇类占总量的8.6%。茶检测到26种化合物,其中:5种酯类占总量的40.8%,主要有乙酸叶醇酯、丁酸辛酯、丁酸庚酯;萜类有8种,占总量的17.9%;4种醛类占总量的13.0%;3种醇类占总量的5.2%;2种酮类占总量的5.1%。

序号 保留时间/min 挥发性有机物 化学式 峰面积/(×105 g−1) 杨梅 青梅 茶 1 6.941 己烯醛2-hexenal C6H10O − 2.24±0.52 − 2 7.113 顺式-3-己烯醇cis-hex-3-en-1-ol C6H10O − 14.03±3.02 − 3 7.913 壬烯nonene C9H18 − − 5.57±0.76 4 8.232 庚醛heptanal C7H14O − − 2.68±0.45 5 8.652 苯甲醚anisole C7H8O − − 21.64±3.38 6 8.655 茴香醚anisole C7H8O − 1.66±0.34 − 7 9.070 α-蒎烯α-pinene C10H16 4.57±1.56 4.32±0.26 2.10±0.73 8 9.711 1,4-环己二烯1,4-cyclohexadiene C10H14 0.47±0.07 − 5.96±0.66 9 10.708 月桂烯myrcene C10H16 5.99±3.59 3.34±0.31 − 10 11.023 辛醛octyl aldehyde C8H16O − 3.39±0.88 5.76±0.37 11 11.150 乙酸叶醇酯cis-3-hexenyl acetate C8H14O2 − 90.40±8.80 59.16±4.67 12 11.230 对二氯苯para-dichlorobenzene C6H4Cl2 0.49±0.01 13.98±1.44 9.94±0.55 13 11.586 邻伞花烃0-cymene C10H14 − − 2.15±0.76 14 11.693 柠檬烯limonene C10H16 38.07±2.00 3.34±0.97 5.64±0.26 15 12.228 罗勒烯ocimene C10H16 43.46±1.54 4.65±3.77 6.70±0.22 16 13.478 紫苏烯perillene C10H14O 2.86±0.86 − 2.07±0.24 17 13.596 里哪醇linalool C10H18O 7.07±2.04 − 2.69±4.00 18 13.695 壬醛nonanal C9H18O 4.02±0.89 12.90±4.36 11.34±0.18 19 13.999 松香芹酮pinocarvone C10H14O 1.64±0.36 8.97±2.46 8.70±1.19 20 14.144 杜烯durene C10H14O 7.90±0.90 − − 21 14.357 香芹醇(-)-carveol C10H16O 55.35±4.55 1.70±0.37 − 22 14.652 别罗勒烯allo-ocimene C10H16 4.01±1.49 − − 23 14.754 莰酮cmaphenone C10H16O − − 1.50±0.39 24 15.467 薄荷醇menthol C10H20O − − 2.17±0.57 25 15.744 甘氨酰肌氨酸glycinosinine C5H10N2O3 − − 4.39±0.80 26 16.083 水杨酸甲酯methyl salicylate C8H8O3 − 2.82±0.28 6.17±1.02 27 16.353 癸醛decanal C10H20O − 5.09±1.58 6.18±1.03 28 21.249 丁酸庚酯heptyl butyrate C11H22O2 − − 4.36±0.40 29 21.878 丁酸辛酯octyl butyrate C12H24O2 − 5.73±0.68 8.56±1.47 30 22.983 α-柏木烯α-cedrene C15H24 − 4.64±0.34 2.35±1.35 31 23.183 石竹烯caryophyllene C15H24 17.83±2.17 − 3.35±0.65 32 23.458 别香橙烯allo-aromadendrene C15H24 5.73±0.23 − − 33 24.085 α-草烯α-humulene C15H24 98.08±1.92 − − 34 25.074 花柏烯chamigrene C15H24 13.86±1.14 − − 35 25.093 β-瑟林烯β-selinene C15H24 6.63±1.13 − − 36 25.265 蛇床烯selinene C15H24 11.57±1.64 − − 37 26.515 桉叶醇eudesmol C15H26O 1.22±0.11 − − 38 27.497 雪松醇cedar camphor C15H26O − − 5.48±1.11 39 28.263 斯巴醇spathulenol C15H24O 4.35±0.72 − − 40 28.675 石竹烯氧化物caryophyllene oxide C15H24O 9.72±0.33 − − 41 31.655 肉豆蔻酸异丙酯isopropyl myristate C17H34O2 − − 3.28±1.79 说明:“−”表示未测到化合物 Table 1. VOCs components of 3 evergreen plants

比较3种常绿树释放的VOCs成分,杨梅释放VOCs总量最大,其次为茶、青梅。杨梅释放的VOCs主要是α-草烯;青梅和茶释放VOCs均以乙酸叶醇酯为主,但是茶特有的醛类VOCs是庚醛,而青梅特有的醛类是己烯醛。

-

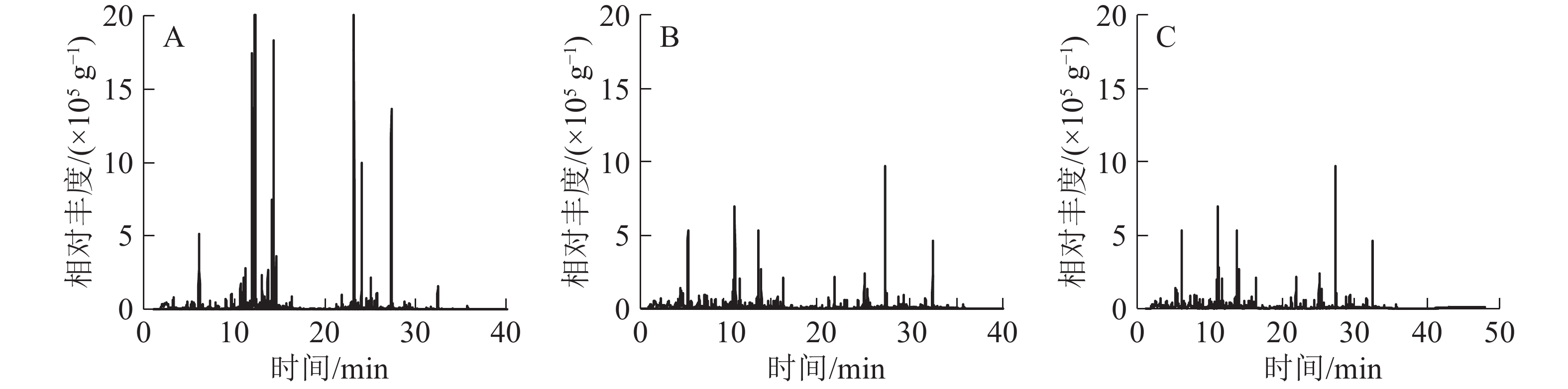

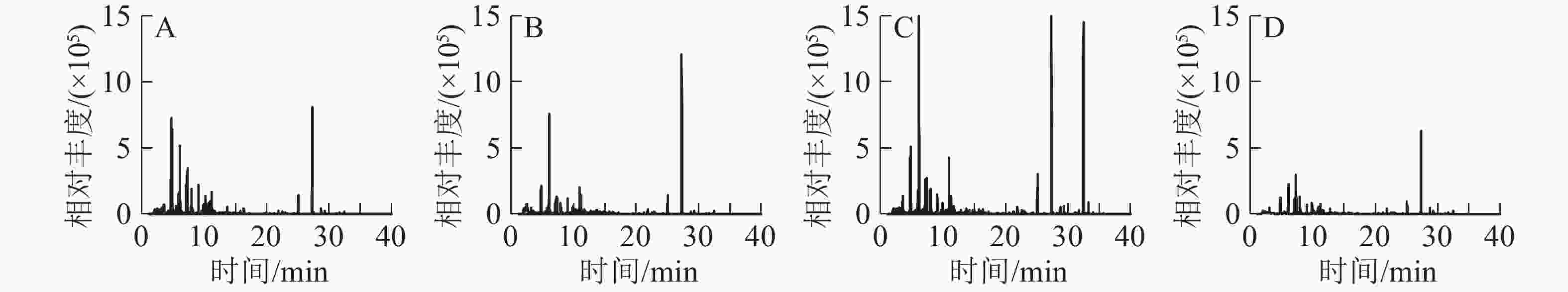

从图2和表2可以看出:空气中的VOCs总量从高到低分别为青梅园、茶园、杨梅园、空旷地。空气中主要是以苯类为主,也有少量的萜烯类,这些萜烯类化合物在植物中也存在。空旷地检测出12种物质,其中:5种苯类占总量的74.2%,2种萜烯类占总量的10.3%,3种烷烃类占总量的11.9%,2种醛类占总量的3.6%。杨梅园空气中VOCs共检测出10种物质,4种苯类占总量的54.8%,3种萜烯类占总量的35.6%。青梅园空气中VOCs共检测出9种物质,3种苯类占总量的35.4%,4种萜烯类占总量的52.2%,1种醛类占总量的3.1%。茶园空气中检测出13种化合物,包括4种苯类占总量的50.1%,5种萜烯类占总量的36.5%。

序号 保留时间/min 有机挥发物 化学式 峰面积/(×105 g−1) 空旷地 杨梅园 青梅园 茶园 1 7.116 乙苯ethylbenzene C8H10 13.98±5.26 59.43±7.27 − 57.85±1.59 2 7.326 对二甲苯p-xylene C8H10 21.01±7.82 107.81±8.90 131.51±6.62 98.27±2.25 3 7.914 苯乙烯styrene C8H8 11.32±6.19 125.71±4.70 58.61±2.11 128.58±2.48 4 8.125 壬烷nonane C9H20 1.83±0.77 − − − 5 9.080 α-蒎烯pinene C10H16 4.64±1.36 190.60±4.80 245.10±12.45 143.96±5.53 6 9.484 莰烯camphene C10H16 − 19.33±6.35 25.54±8.06 18.48±2.82 7 9.875 3-乙基甲苯3-ethyltoluene C9H12 4.68±1.32 − − − 8 9.916 枯烯cumene C9H12 − − − 34.70±4.54 9 10.254 蒈烯3-carene C10H16 − − 48.49±4.29 − 10 10.265 桧烯sabinene C10H16 3.11±2.20 − − 17.35±3.25 11 10.625 2,6-二甲基辛烷dimethyloctane C10H22 2.64±0.57 19.15±1.80 − 21.86±4.05 12 11.246 对二氯苯para-dichlorobenzene C6H4Cl2 4.90±1.08 47.35±1.06 40.95±5.09 30.52±0.93 13 11.580 间伞花烃m-cymene C10H14 − 22.59±2.85 − 25.55±3.43 14 11.703 柠檬烯limonene C10H16 − 11.00±7.78 21.68±1.07 15.11±2.16 15 13.695 壬醛nonanal C9H18O 1.58±0.37 − 19.98±4.13 − 16 16.339 癸醛decanal C10H20O 1.17±0.83 − − − 17 21.886 丁酸辛酯butyric acid, octyl ester C12H24O2 − − − 22.61±1.12 18 25.089 十五烷pentadecane C15H32 4.49±2.62 17.66±3.33 61.14±3.69 14.03±9.92 说明:“−”表示未测到化合物 Table 2. Air VOCs composition in three evergreen plants gardens

比较3种常绿树园和空旷地空气的VOCs发现:青梅园VOCs总量最高,其次为茶园、杨梅园。杨梅园、青梅园和茶园萜烯类化合物均高于35%。从萜烯类化合物总量从高到低依次为青梅园、茶园、杨梅园,苯类化合物总量从高到低依次为空旷地、杨梅园、茶园、青梅园。

-

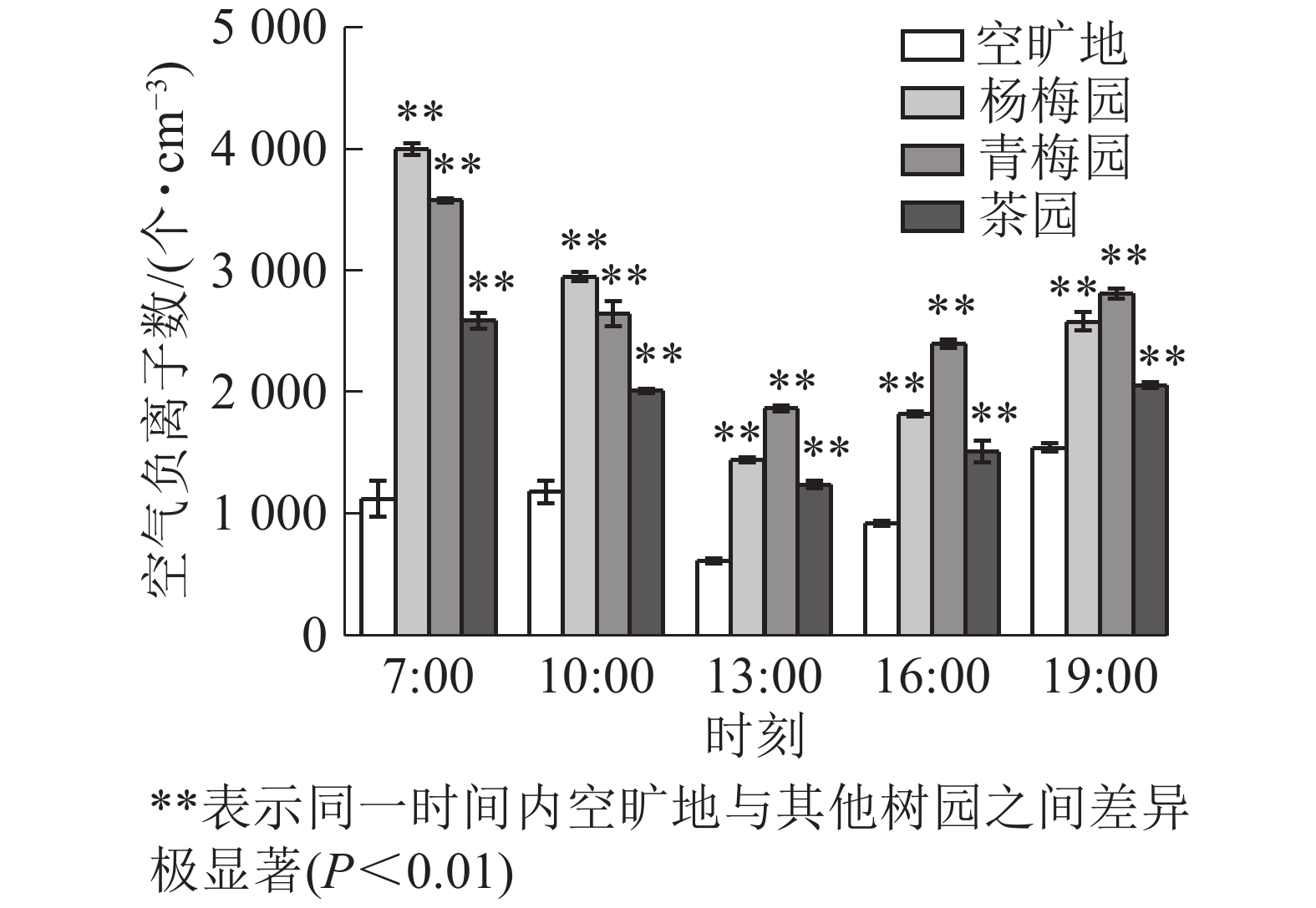

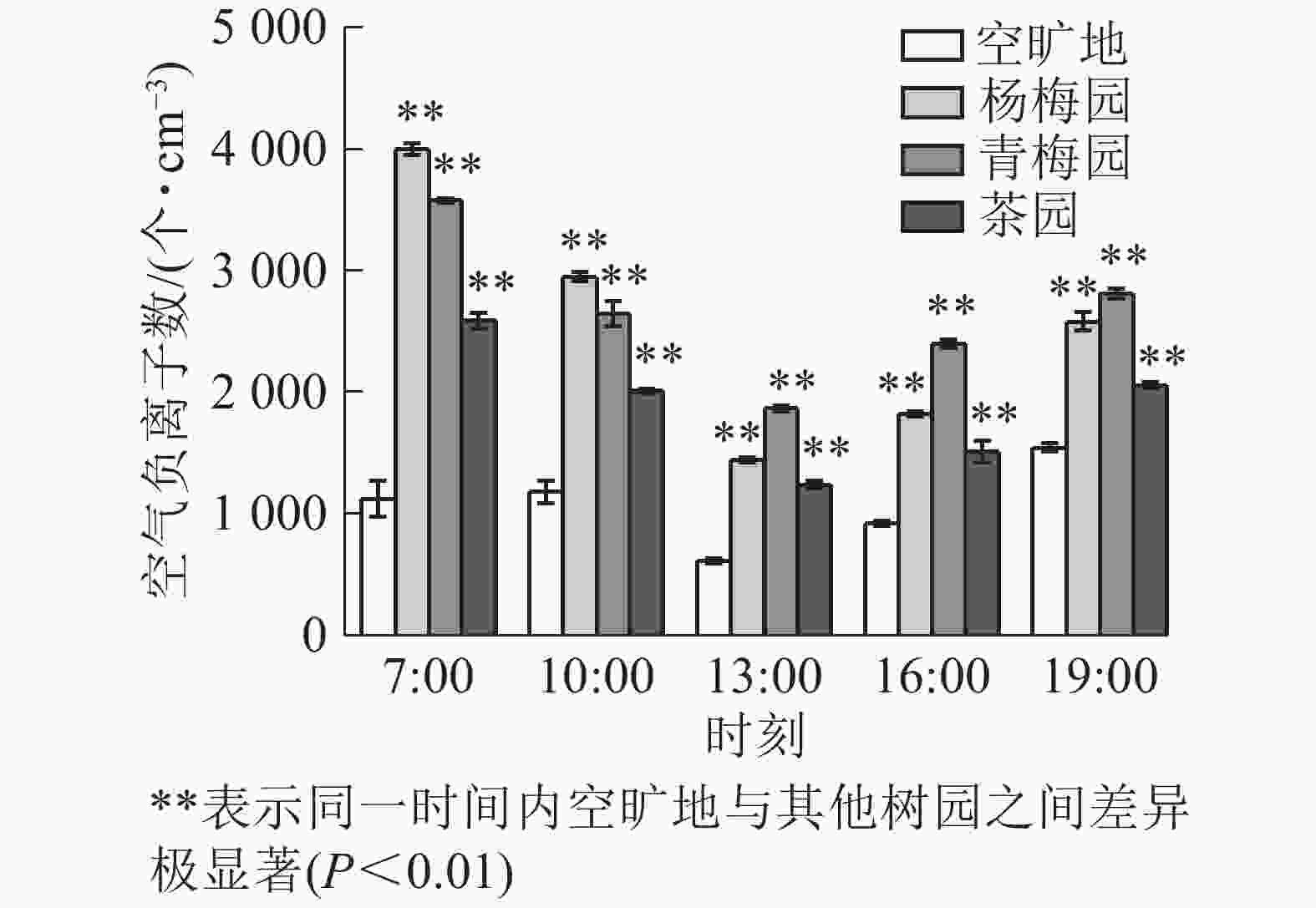

由图3可知:空气负离子数在13:00最低,在7:00和19:00最高。杨梅、青梅、茶园内、空旷地日平均值分别为2 559.2、2 660.0、1 878.4、1 078.8个·cm−3。杨梅园中在7:00空气负离子数最高,13:00比7:00减少了63.9%,19:00比13:00增加了44.0%;青梅园中的负离子数,13:00比7:00减少了47.8%,19:00比7:00减少了21.4%;茶园中的负离子数7:00比13:00多51.6%,比19:00多19.9%。

-

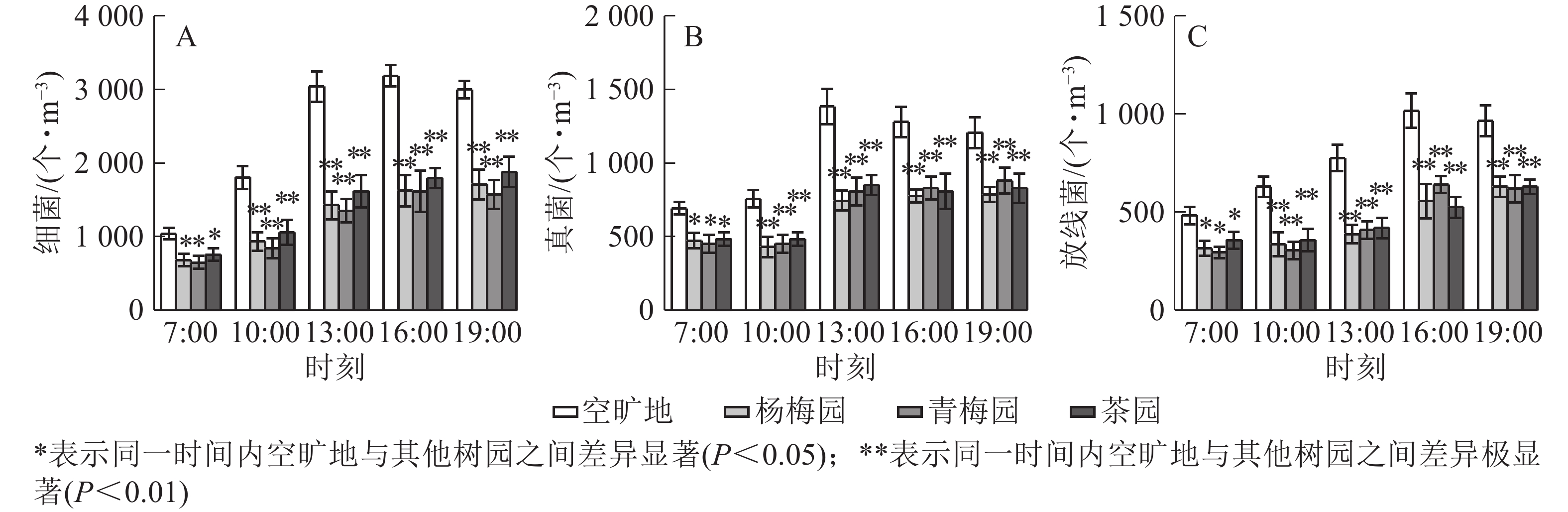

从图4A可以看出:空旷地细菌数量明显高于杨梅园、青梅园和茶园。杨梅园、青梅园和茶园均在13:00降幅最大,分别比空旷地降低了53.1%、55.5%和46.9%。茶园细菌数量高于杨梅园和青梅园。在7:00、10:00、13:00、16:00、19:00,茶园细菌数量比空旷地明显下降,分别下降了27.3%、41.3%、46.9%、43.8%和37.4%(P<0.01),表明不同园子内随着时间的变化,细菌数量明显不同。从图4B可以看出:杨梅园、青梅园和茶园真菌的数量低于空旷地。各园真菌数量在13:00降幅最大,杨梅园、青梅园和茶园比空旷地分别降低了46.2%、41.7%、38.6%。13:00−19:00空气中的微生物数量明显高于7:00−13:00。从图4C可以看出:空旷地放线菌数量高于杨梅园、青梅园和茶园。杨梅园在13:00抑制率最大,青梅园在10:00降幅最大,茶园在16:00降幅最大,分别降低了50.0%、51.7%、48.5%。各园放线菌降幅程度在16:00−19:00明显高于7:00−13:00。

-

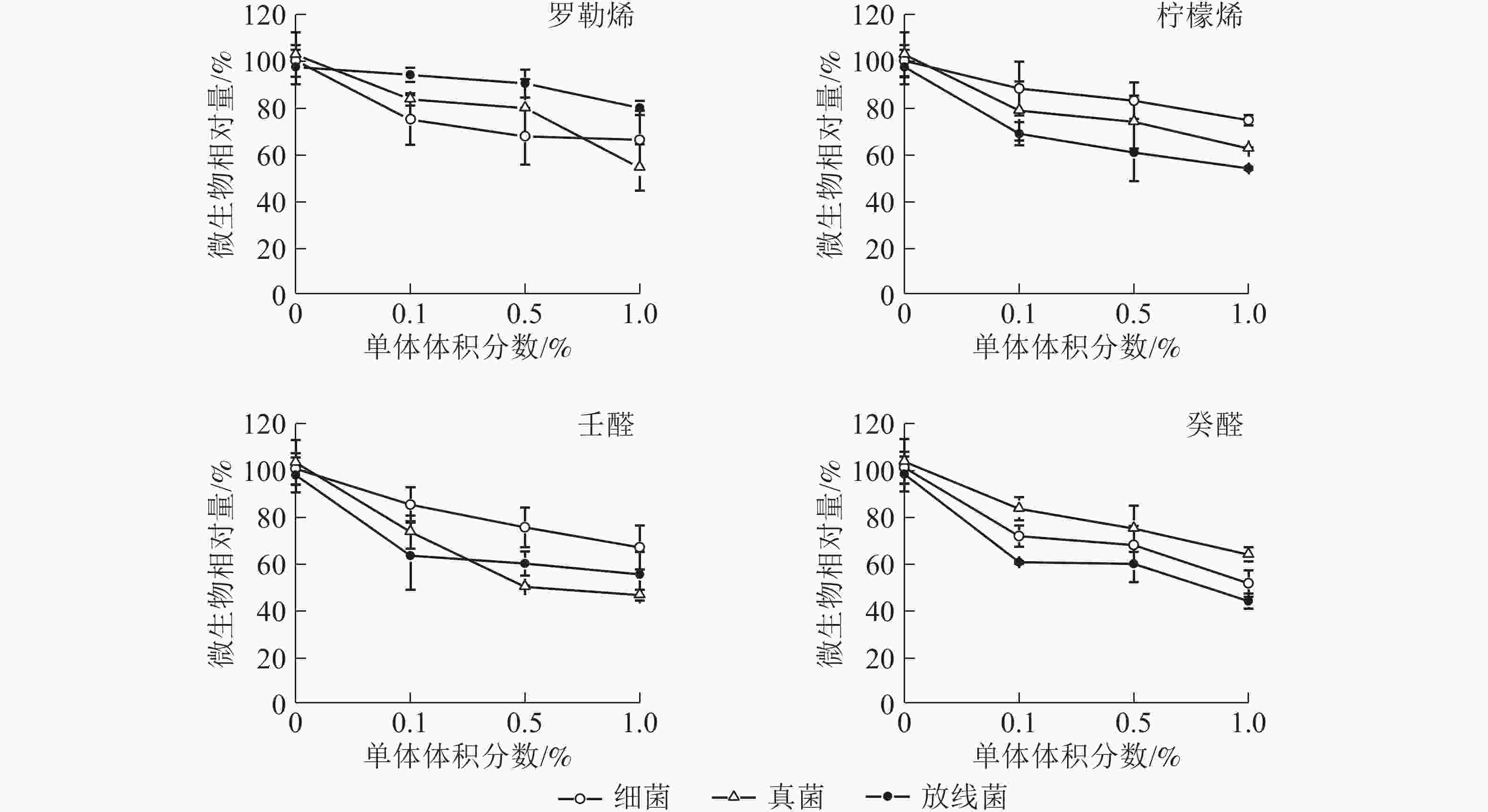

在单体体积分数为0.1%~0.5%的水平下,罗勒烯抑制细菌的生长效果比柠檬烯明显,在体积百分比为1.0%的水平下,罗勒烯抑制真菌生长的效果比柠檬烯更有效,而柠檬烯抑制放线菌的作用比罗勒烯更强(图5)。2种单体醛对空气微生物具有明显的抑制作用,体积分数为1.0%的壬醛对细菌、真菌和放线菌的抑制率分别为33.1%、43.4%和54.5%;体积分数为1.0%的癸醛对细菌、真菌和放线菌的抑制率分别为48.6%、37.4%和56.1%。在4种单体中,醛类比萜烯类抑制速率更大,醛对细菌、真菌和放线菌生长有明显的抑制作用。

2.1. 3种常绿树VOCs成分分析

2.2. 3种常绿树园空气VOCs分析

2.3. 3种常绿树园空气负离子的比较

2.4. 空气微生物分析

2.5. 单体对空气微生物的影响

-

植物基因型是决定VOCs种类和含量的重要因素,植物种属间的差异导致释放出的VOCs物质种类与比例具有明显的差异[21]。吴章文等[22]研究发现:8种柏科Cupressaceae(崖柏Thuja sutchuenensis、日本扁柏Chamaecyparis obtusa、干香柏Cupressus duclouxiana、柏木Cupressus funebris、西藏柏木Cupressus torulosa、侧柏Platycladus orientalis、圆柏Sabina chinensis、叉子圆柏Sabina vulgaris)植物释放的VOCs以萜烯类物质为主;迷迭香Rosmarinus officinalis[23]和雪松Cedrus deodara[24]释放的VOCs虽然都是萜烯类物质,但是种类和含量各不相同。本研究显示:茶叶片VOCs是以乙酸叶醇酯为主,与乔如颖等[25]的研究一致,因为白茶叶片富有茸毛,而茸毛是储存、合成VOCs的场所,叶表面附着大量的己烯醛和己烯醇,它们都是合成乙酸叶醇酯的前体,所以乙酸叶醇酯最高。MIYAZAWA等[26]研究发现:青梅果实在未成熟时以醛类物质为主,而成熟期时以酯类物质为主,这与本研究结果相同。杨梅叶片VOCs以萜烯类物质为主,主要是α-草烯,与尹洁等[27]发现杨梅叶中的VOCs主要是α-葎草烯的研究结果一致。

植物能够产生大量的空气负离子是由于存在植物叶片“尖端放电”[28]和“光电效应”[9]的现象。白保勋等[29]研究发现:年均空气负离子数量从高到低依次为森林、果园、农田、绿地;王洪俊[30]发现:乔灌草复层结构、灌草结构、草坪空气负离子数量依次递减。本研究表明:杨梅园、茶园和青梅园的空气负离子日平均数量明显高于空旷地。植物VOCs能够促进空气电离,有助于形成空气负离子,从而增加空气负离子的数量,萜烯类化合物有重要促进作用。3种树园中的空气负离子数量日变化呈早晚较高,中午低的趋势,可能原因是早晚湿度大、温度低影响了空气负离子数量,中午温度和光照强度逐渐增高,植物为了减少蒸腾作用,关闭气孔,植物VOCs释放的速率下降,从而空气负离子数量减少。

植物释放的VOCs具有重要的生态学功能,参与植物直接与间接防御反应,同时防止病菌及微生物的感染。SALEM等[31]和BEHBAHANI等[32]分别研究发现:桉树Eucalyptus robusta油和橄榄Canarium album精油对细菌具有较强的抑菌作用。GAO等[19]研究发现:醛类物质也具有抑菌作用。本研究显示:杨梅园、青梅园和茶园中都有α-蒎烯、莰烯、柠檬烯和壬醛,且细菌、真菌和放线菌的相对含量明显低于空旷地,说明植物VOCs对微生物的生长有抑制作用。同时采用植物VOCs较高的罗勒烯、柠檬烯、壬醛和癸醛对空气微生物的抑制作用发现:随着单体体积分数的增加,抑制效果也逐渐增强,在高体积分数时抑菌效果最明显;醛类物质抑制细菌、真菌和放线菌的效果比萜烯类更明显。杨梅园、青梅园、茶园的空气微生物相对含量低于空旷地,说明罗勒烯、柠檬烯、壬醛和癸醛在植物中可能是抑菌的主要物质[19, 33]。

植物VOCs和空气负离子是森林康养的重要组成部分,森林康养是依托植物释放对人有益的VOCs和杀菌素,能够增加空气负离子[34]和提高人的免疫力[35],是改善人类身心健康的一种疗养方式[36]。同时能够降低促炎细胞因子和应激激素的水平[36],无论是生理上还是心理上都能得到放松[37]。空气负离子能够调节人的内循环系统,对气管炎、冠心病、脑血管等疾病具有一定的疗效[38]。杨梅园中存在对人有益的VOCs,如α-草烯、罗勒烯、柠檬烯、花柏烯和石竹烯;茶园存在对人有益的VOCs有α-派烯、罗勒烯、柠檬烯,还有抑制微生物生长的庚醛、苯甲醛、辛醛、壬醛;青梅园中有对人有益的VOCs有α-柏木烯、罗勒烯、柠檬烯,也存在壬醛、癸醛和辛醛。总的来说,3种常绿树园在早晚时空气负离子达到最高状态,微生物的抑制效果亦是最强的。

综上所述,杨梅释放的VOCs主要以萜烯类为主,青梅和茶均以酯类为主;3种常绿树园都能释放出对人体有益的VOCs组分,它能够抑制空气微生物的生长,同时具有促进空气负离子形成和改善空气质量的作用。青梅园内的空气负离子比其他园林高,3种常绿树园内的空气质量在7:00和19:00较好,中午最差;园内微生物中细菌相对含量最高,真菌次之,放线菌最少。茶园的微生物(细菌、真菌、放线菌)相对含量居首位,从7:00−19:00呈逐渐增加的趋势。细菌抑制率最高的是青梅园,真菌和放线菌抑制率最高的是杨梅园。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: