-

研究木质纤维原料化学成分的含量及在细胞壁中的分布有助于对木质纤维原料进行综合高效的利用,是制订生产工艺的基本依据,也是实现木纤维生物质增值利用和循环经济的关键[1-2]。木质纤维原料由木质素、纤维素和半纤维素组成,纤维素构成纤维细胞壁的主要框架结构,半纤维素和木质素填充在纤维以及微细纤维之间,其中,木质素又以三维网状结构镶嵌在木质纤维原料中。纤维素、半纤维素和木质素彼此通过物理的或化学的链接方式构建成一个立体、致密、复杂的网络结构,该结构具有抵抗外力以及抵抗微生物侵蚀的能力[3-4]。这种多组分的存在以及彼此之间复杂的化学或物理的链接,导致木质纤维中各组分不易被分离出来。尤其对于复杂组分的木质纤维,需要借助木质纤维原料的全溶体系,通过不破坏各组分结构、没有衍生反应,最终将各组分以高得率、高纯度分离出来。木质素是研究比较多的纤维原料的化学成分,对木质素的认知一直基于降解后的结构已破坏的木质素,一般也是用分离后的木质素进行诸如核磁共振(NMR)的波谱分析来获取木质素的结构相关信息,即使固相的木质素NMR也不能给出足够的结构信息[5-6]。有关木质纤维原料的溶剂近年研究较多[7-10],氯化锂/二甲基乙酰胺(LiCl/DMAc)可以溶解纤维素,但不能溶解含有一定木质素的浆料[11-12],木质素经过衍生反应后却可以溶解在LiCl/DMAc体系中[13]。在木质纤维原料的溶解方面,木质素是重要的影响因素[14]。氯化锂/二甲基咪唑(LiCl/DMI)毒性低、热稳定性好,可用于纤维素的均相反应体系的溶解[15-16],纤维素的添加量可以高达10%[17-18],但若换成硫酸盐针叶材浆料,且浆料中木质素添加量低至2.0%,至少需要2周溶液才能完全澄清[19]。氯化锂/二甲亚砜(LiCl/DMSO)溶剂体系为高聚物的反应溶剂介质[20-21],WANG等[22]将LiCl/DMSO用于木质纤维原料的溶解,得到了木质纤维素全溶体系,经水再生后纤维素的结晶度会下降,但木质素的含量及其结构没有受到影响。LiCl/DMSO既可以用于全面分析木质素组分,也为分离细胞壁中纤维素、半纤维素、木质素提供了一个可能的溶剂体系[23-24]。本研究以非木材稻草(水稻Oryza sativa秸秆)为原料探讨稻草在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系的溶解行为及再生特点,为全面解析稻草原本木质素结构信息提供一个理想可行的全溶溶剂体系,实现对原本木质素的高得率、高纯度的分离。

HTML

-

稻草取自日本某农场,原料风干后,选取不带节的秆、带节的秆、叶及全秆,手工剪成30~50 mm的草片。草片原料再用Wiley微型粉碎机粉碎,收集40~80目组分,用苯-乙醇溶液(体积比为2∶1)进行脱脂抽提8.0 h,真空干燥后,储存于广口瓶中,供分析使用。

-

采用Pulverisette 7微型行星式高能球磨机(Fritsch)进行球磨。在45 mL氧化锆制的罐子里称取4.0 g干燥后的脱脂草粉,内装18只内径1 cm的氧化锆圆球,在600 r·min−1条件下进行0.5,1.0 h不同时间的球磨,每运行5 min,休停10 min,以避免设备过热。球磨草粉经真空干燥后,装瓶备用。

-

配制LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系,其中LiCl质量分数分别为2%、4%、6%、8%。称取不同球磨时间获得的草粉,在室温下按照质量分数为8%添加量在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中进行磁力搅拌48.0 h。

-

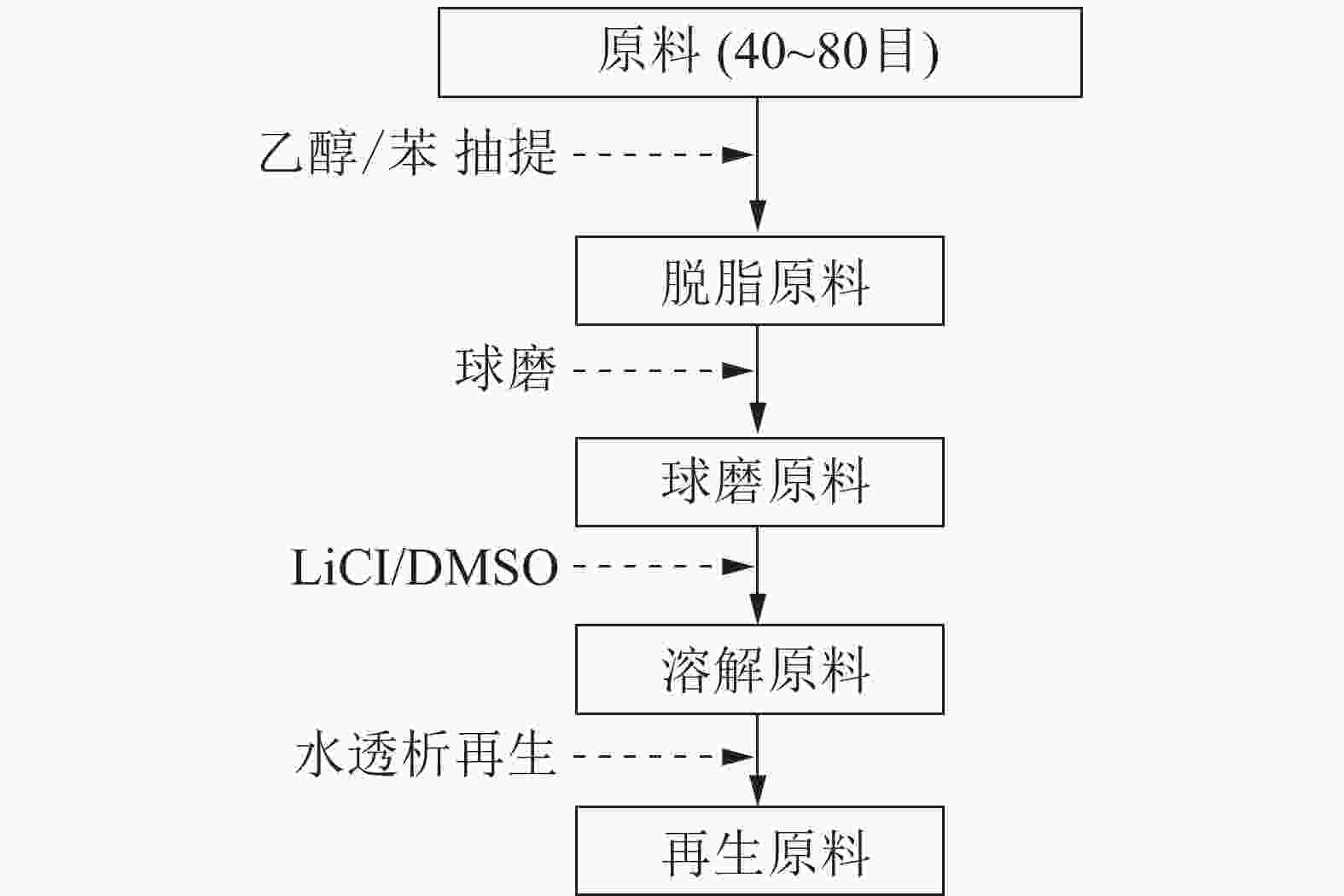

LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理脱脂原料的流程如图1所示。球磨稻草粉用质量分数为6% LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理,完全溶解后,整个混合体系移入透析袋(孔径50 Å、直径28 mm、透过分子量为14 000),将透析袋浸入去离子水中进行透析,隔4 h换1次水,每次用硝酸银(AgNO3)溶液检测透析液中有无氯离子(Cl¯),直至完全置换出LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系。透析后的物料经冷冻干燥、真空干燥后,得到球磨的再生原料,装瓶备用。

-

木质素的结构单元通过硝基苯氧化结果来分析[27]。

-

纤维结晶指数分析在日本理学Ultima IV组合型多功能水平X射线衍射仪上进行,采用粉末法。结晶指数计算参考文献[28]。

1.1. 原料

1.2. 球磨

1.3. LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系的溶解

1.4. LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系的再生

1.5. 分析方法

1.5.1. 化学成分测定

1.5.2. 硝基苯氧化

1.5.3. X射线衍射

-

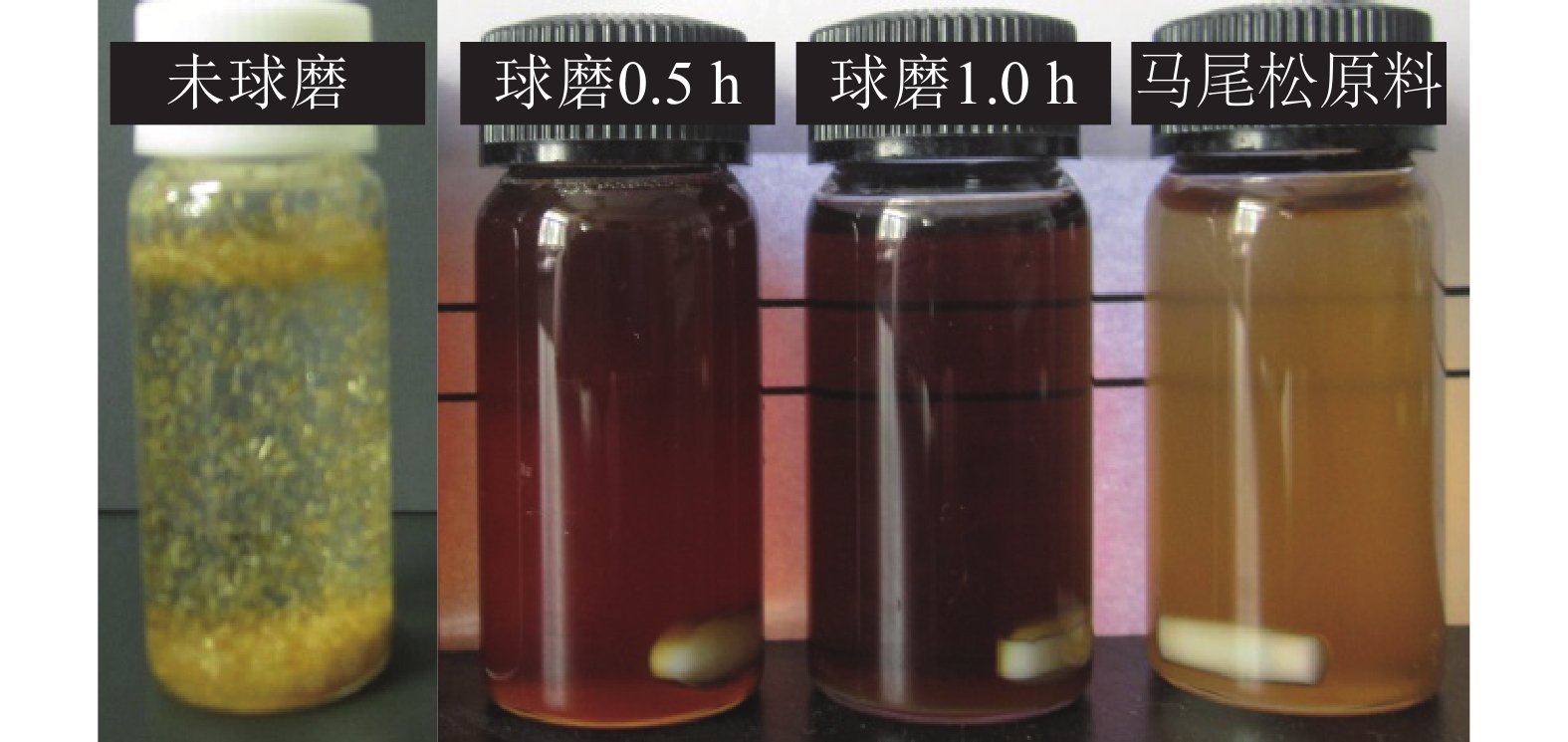

由图2和图3所示:随球磨时间的不同,稻草各部位在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中呈现不同的溶解性能。球磨0.5 h时,稻草叶和秆在质量分数为6%LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中有明显的混浊,随着球磨时间的增加,稻草叶、秆在溶剂中溶解得更为透彻,球磨1.0 h时能得到澄清透亮的溶液。木质纤维原料的比表面积大小及化学成分组成对溶解的难易程度影响很大,木质纤维原料的粒径越小其溶解越容易。相较于球磨,未球磨的40~80目的草粉在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中呈混浊状,静置片刻会有明显的固液分层。木质材料纤维细胞的细胞壁结构十分复杂,纤维素、半纤维素和木质素都会阻碍有机离子液体向木质纤维素内部扩散。其中纤维素的结晶区、木质素的三维网络结构特点、各组分之间的复杂链接等使得木质纤维原料不能溶于一般的溶剂中。另外,稻草中灰分含量较高。当球磨时间为1.0 h时,稻草的叶、秆组分可完全溶解在质量分数为6% LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中。而球磨1.0 h的马尾松Pinus massoniana原料在质量分数为6% LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中并不能完全溶解。即使同样的溶剂体系,山毛榉Fagus crenata、云杉Picea abies脱脂木粉需要经过球磨处理2.0 h后才能全部溶解[22]。稻草和木材化学成分不同,稻草的木质素含量相对较低,灰分含量相对较高,质地结构相对于木材较为疏松[29],因此可以在球磨处理较轻的条件下被溶解。稻草各部位都很容易溶于LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系,化学组成的差异性会影响稻草在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中的溶解量,稻草叶、秆在质量分数为6% LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中可溶解的质量百分数达8%。

-

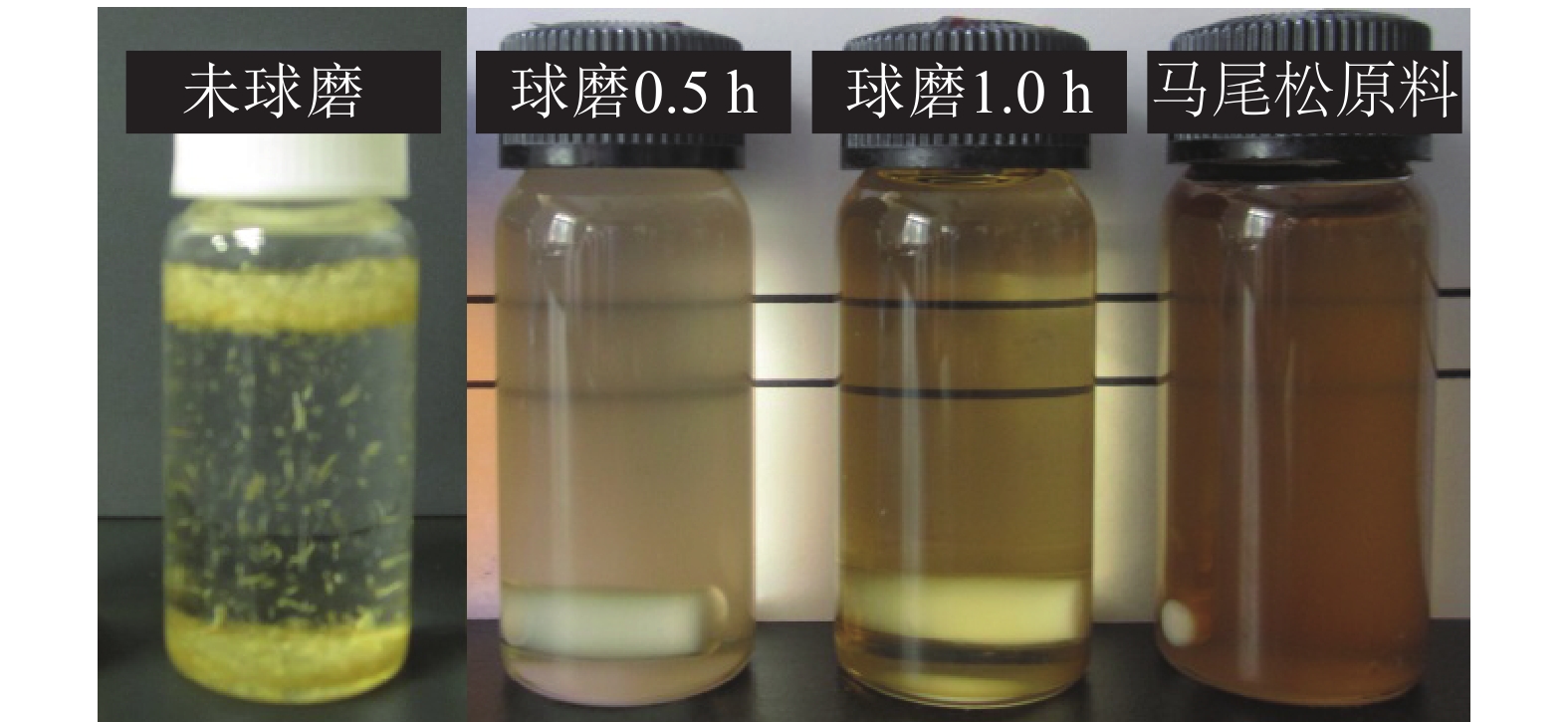

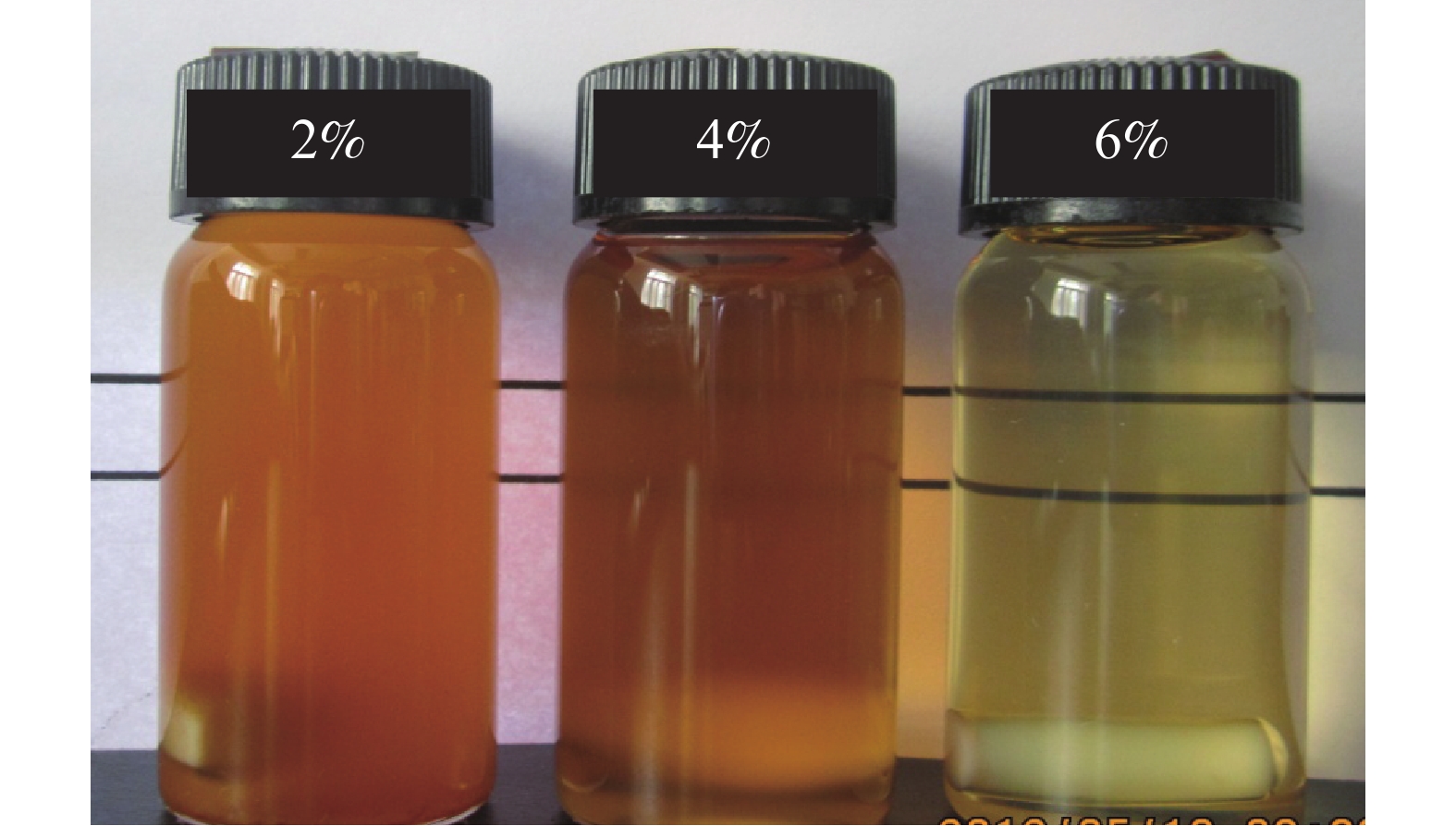

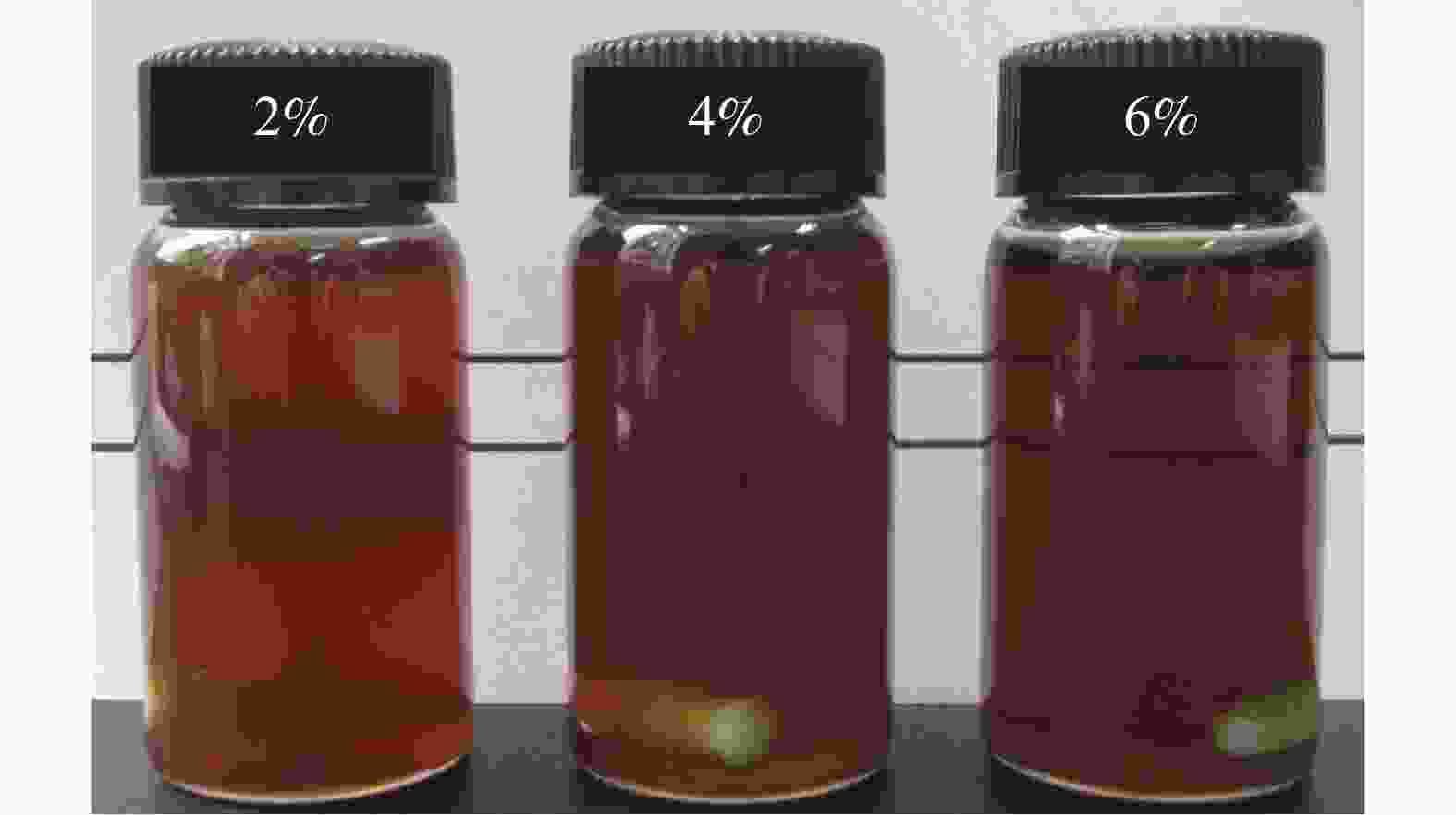

图4和图5为球磨1.0 h的稻草叶、秆在不同质量分数LiCl/DMSO中搅拌48.0 h的溶解性能。木质纤维原料的溶解能力可认为是溶剂对碳水化合物和木质素之间形成的这些错综复杂的网络结构的有效突破。LiCl/DMSO作为复合溶剂,每个溶剂成分在溶解过程发挥各自作用,且又通过协同作用最终溶解目标物。随着LiCl质量分数的逐步增加,稻草叶、秆溶于LiCl/DMSO溶剂中的溶液透明度越来越高,说明稻草溶解越充分。当LiCl在DMSO中的质量分数达到6%时,稻草叶、秆的溶液已完全透明。在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中,Cl−与纤维素分子中羟基上的氢结合,形成氢键并破坏纤维素晶格中原有氢键网络[20],DMSO通过破坏分子间和分子内的氢键使微纤丝发生润胀,随着LiCl质量分数的逐步增加,Cl−增多,更多的纤维素原有氢键被打开,并被阻止重建。球磨1.0 h稻草叶和秆都能溶于质量分数6.0%的LiCl/DMSO溶剂中。在更高的LiCl质量分数下,能溶解的物质的量也高,在质量分数8.0%的LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中球磨1.0 h稻草叶粉和秆粉的溶解量可达到10%。

-

由表1可知:与木材的化学组成相比,稻草中半纤维素含量较多,灰分含量高,木质素含量少。稻草的不同部位在化学成分上也有很大的差异,稻草叶中灰分高达212.1 mg·g−1,高于稻草秆,而秆中的高聚糖质量分数要高于叶。木质素在稻草中的分布也不均一,在叶中为168.7 mg·g−1,在秆中146.5 mg·g−1。带节的茎秆与不带节茎秆在化学成分上相近;稻草叶在稻草中所占的比例最大,因此,稻草全秆在化学成分上更接近于稻草叶。

稻草原料 木质素/(mg·g−1) 高聚糖/(mg·g−1) 灰分/(mg·g−1) 酸不溶 酸溶 总木质素 葡聚糖 木聚糖 其他 总糖 带节的秆 110.1 36.4 146.5 428.2 153.5 35.4 617.1 165.6 不带节的秆 111.1 35.4 146.5 408.0 168.7 40.4 617.1 168.7 叶 120.2 48.5 168.7 348.5 149.5 39.4 547.4 212.1 全秆 124.2 37.4 161.6 359.6 164.6 47.5 570.7 190.9 Table 1. Chemical compositions of extractive free straw samples

-

稻草经球磨1.0 h,用质量分数为6%LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理,并在水中通过透析再生,得到再生稻草样品。由表2可知:球磨稻草再生原料中的木质素在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理过程中有一定程度的下降,其中,稻草不带节茎秆和带节茎秆的木质素和高聚糖的再生能力强于稻草叶和全秆。稻草不同部位对LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系的再生响应不同,酸溶木质素质量分数在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系溶解再生过程中几乎没变化。球磨时间和LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中LiCl的质量分数对再生原料中木质素质量分数有一定影响。

再生原料 木质素/(mg·g−1) 高聚糖/(mg·g−1) 灰分/(mg·g−1) 留着率/% 酸不溶 酸溶 总木质素 留着率a/% 葡聚糖 木聚糖 总糖 留着率b/ % 带节的秆 104.0 22.2 126.3 86.3 395.9 124.2 552.5 89.5 53.5 89.0 不带节的秆 105.0 22.2 128.3 87.5 364.6 139.4 540.4 87.7 55.6 89.9 叶 109.1 23.2 132.3 80.5 313.1 127.3 456.5 83.5 101.0 80.5 全秆 109.1 23.2 131.3 81.0 332.3 135.3 486.8 85.4 92.9 86.5 说明:球磨2.0 h的稻草再生原料。a基于原料中木质素;b基于原料中高聚糖 Table 2. Chemical compositions of regenerated straw samples with ball milling

从表2可以看出:水再生处理后,稻草4个不同部位木质素留着率为81.0%~86.3%,这个结果与经过相同处理的木粉木质素的留着率是一致的[22]。球磨2.0 h的木粉完全溶于质量分数为6%LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中,经水再生后,木质素的留着率约85.8%。稻草中更多木质素的溶出可能由于LiCl在DMSO中的溶解度偏大(8%)。另外,木材与非木材的化学组成、化学结构、紧致程度也有所不同。球磨样品经LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理后,高聚糖质量分数没有明显变化。稻草不同部位对LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理的响应不同,稻草叶中的化学成分溶出相对较多,可能由于稻草秆的结构比较紧密,稻草叶质地疏松,因此稻草叶更易溶解在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中。秆和叶中的灰分在溶剂体系中的处理效果也有所不同,经溶剂体系处理后,秆中的灰分为55.6 mg·g−1,溶出约70%,而叶中的灰分为101.0 mg·g−1,几乎保留了原料中一半的灰分。可见经过LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理后,稻草叶中的灰分更易保留。

-

球磨时间的长短会影响木质素的结构,一般球磨时间越长,木质素结构被破坏越严重[30−31]。木质素是由3种苯丙烷结构的先体通过醚键和碳碳键联接而成的具有三维立体结构的天然高分子聚合物。根据芳香核的不同,3种苯丙烷结构分别为愈创木基丙烷、紫丁香基丙烷、对-羟基苯丙烷。针叶材的木质素主要有愈创木基丙烷单元构成,阔叶材木质素主要由愈创木基丙烷和紫丁香基丙烷的结构单元构成,草本植物木质素的结构则包括愈创木基、对羟基苯基及紫丁香基丙烷单元。碱性硝基苯氧化反应一般用于木质素的结构单元分析,未缩合的对羟基苯基、愈创木基和紫丁香基单元在高温碱性条件下分别氧化为对羟基苯甲醛或酸(H)、香草醛或酸(V)和紫丁香醛或酸(S)。木质素结构中未缩合单元含量越高,意味着木质素的缩合程度就越低。由表3可知:稻草叶中木质素结构未缩合单元的得率为1.0~1.4 mmol·g−1,稻草秆为1.3~1.6 mmol·g−1,稻草秆的未缩合单元得率要高于稻草叶,稻草中不同部位的木质素化学结构上有一定差异,其中叶中的木质素缩合程度最高,这与MIN等[32]对玉米Zea mays秸秆木质素结构的研究结果一致。球磨1.0和0.5 h草粉的未缩合单元的氧化结果差异不大,但球磨1.0 h的稻草各部位未缩合单元产物的得率高于未球磨的脱脂原料,经过溶剂体系再生处理后,得率又有所下降。这种再生特征与木粉不同,球磨1.0 h的稻草,机械作用对木质素的结构有一定的影响,机械处理改善了硝基苯氧化的均相性。随球磨时间的延长,木质素的未缩合单元产物的得率稍有增加,球磨的机械处理会释放出一定量的愈创木基、对羟基苯基及紫丁香基基本结构单元,导致硝基苯氧化产物的得率在稻草叶中提高了32%,稻草秆中提高了19%。另外球磨也会引起一些高聚物解聚反应[33],不同于木材原料,稻草原料的木质素结构中还有对-香豆酸和阿魏酸,并通过—O—键和酯键方式与碳水化合物的结构相链接,这是稻草木质素区别于木材的重要特征[34]。因此,相较于紫丁香基单元,在球磨秆中的对羟基苯基、愈创木基就更易于释放出来,导致球磨原料中S/(V+H)比未球磨脱脂原料要低。球磨1.0 h样品经LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理,再生后,木质素未缩合单元的得率下降不到20%,球磨过程中释放出来木质素结构单元,会溶于LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系并在再生过程中流失,导致S/(V+H)增加。相比较于稻草秆,稻草叶中的木质素未缩合结构单元更容易在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系的再生处理过程中流失。

样品 得率/(mmol·g−1) S/(V+H) 带节秆 不带节秆 叶 全秆 带节秆 不带节秆 叶 全秆 脱脂原料 1.30 1.30 1.01 1.22 0.67 0.67 0.43 0.43 球磨0.5 h 1.60 1.62 1.39 1.51 0.67 0.67 0.43 0.43 球磨1.0 h 1.60 1.59 1.42 1.43 0.43 0.43 0.43 0.43 球磨再生原料 1.42 1.50 1.03 1.21 0.67 0.67 0.67 0.67 说明:S表示紫丁香醛或酸得率;H表示对羟基苯甲醛或酸得率;V表示香草醛或酸得率 Table 3. Nitrobenzene oxidation products yields and S/(V+H) molar ratio of rice straw samples

-

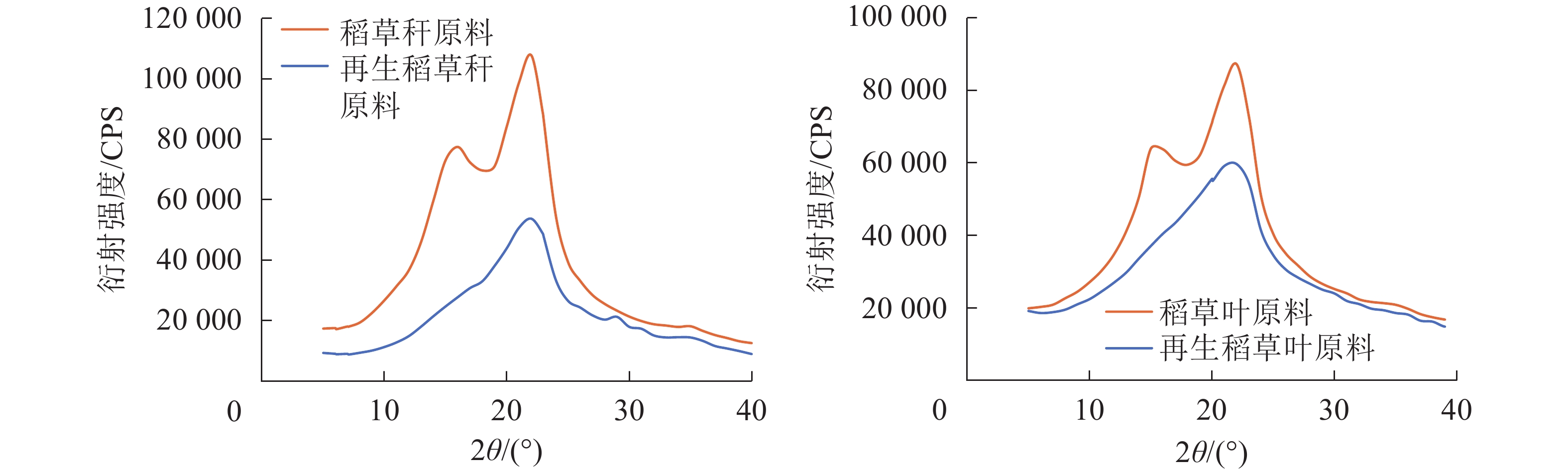

由图6可知:相较于未经处理的原料稻草,球磨1.0 h、经LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系处理再生后原料的衍射曲线其峰形均趋于平坦。由表4可见:叶中纤维素的结晶度由原来的37.8%,经球磨、再生后降低至27.5%,秆则由43.1%降低至26.5%,说明球磨再生处理破坏了原料中纤维素的结晶区,纤维素的聚集态结构遭受了破坏。研究发现:这样的溶解再生处理可以提高木质纤维原料的酶解效率,与未经处理的原料相比,再生处理使纤维素结晶区遭到破坏,促使酶解过程中有更多的高聚糖降解[35-36]。

样品 结晶度/% 稻草叶原料 37.8 再生稻草叶原料 27.5 稻草秆原料 43.1 再生稻草秆原料 26.5 Table 4. Crystallinity of original and regenerated rice straw samples with ball milling

2.1. 稻草在LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中的溶解性能

2.1.1. 不同球磨时间对稻草的溶解性能的影响

2.1.2. LiCl的质量分数对稻草溶解性能的影响

2.2. 稻草LiCl/DMSO溶解体系在水中的再生性能

2.2.1. 稻草原料化学成分

2.2.2. 球磨稻草再生后的化学成分

2.2.3. 稻草再生木质素结构单元的变化

2.2.4. 再生处理对纤维素结晶度的影响

-

稻草中秆和叶经球磨1.0 h后均可完全溶解在质量分数为6%的LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中,溶解的质量分数均达到8%;随着LiCl质量分数的提高,稻草球磨粉在溶剂体系中的溶解度也随之提高,球磨的叶和秆在8%LiCl/DMSO溶剂体系中溶解的质量分数都能达到10%。经水再生后,原料中超过80%的木质素得以保留,秆中木质素保留率可达到87.5%;高聚糖的再生能力要稍高于木质素。在所有化学成分中,叶中纤维素、木质素的再生能力最低;叶、秆中灰分的分布、沉积不同,叶中的灰分再生后约50%保留,且再生能力高于稻草秆。

稻草叶中木质素的缩合程度最高,秆中木质素缩合程度最低;叶和秆经球磨后,木质素的缩合程度均降低,机械处理导致更多的对羟基苯基、愈创木基和紫丁香基单元的木质素结构单元被释放,且秆中以愈创木基和对羟基苯基增加为主。球磨改进了硝基苯氧化环境,反应均相性得到了提高。再生后,各组分缩合程度降低。球磨再生后纤维素结晶区受到一定程度的破坏,结晶度下降。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: