-

在自然界中,植物易受到各种病原物的侵害,植物与病原物协同进化,形成了一系列复杂的防御体系。组成型抗性和诱导型抗性是植物应对病原菌侵害和植食者取食的2种典型的防御机制,植物通过协调不同防御机制实现其最佳防御效果[1]。角质蜡质是植物表皮中由超长链脂肪酸(VLCFAs)及其衍生物构成的一类次生代谢产物。角质蜡质组成的角质层是植物在长期的生态适应过程中,为抵御恶劣生态环境、生物/非生物胁迫而形成的重要保护屏障,广泛参与植物逆境抵御、病虫害防卫等诸多抗性生理过程,在抗病、抗虫、耐盐、抗旱等方面具有重要的生态学功能[2]。近年来,角质蜡质的研究受到各国研究者的持续关注,取得了诸多新进展[3-4]。本研究以植物组成型、诱导型抗性防御反应为主线,归纳总结目前有关角质蜡质代谢及其抗病作用机制的研究进展,以期为植物抗病机理的阐明及相关病害的防治提供研究思路。

-

角质层是植物地上部分一层重要的疏水性保护膜,对植物适应复杂多变的环境具有重要意义[5]。最新研究证实:植物根冠和胚胎中也存在角质层结构,其中根冠角质层在植物应对渗透胁迫和侧根形成中发挥了重要作用,而胚胎角质层则在成熟种子中起着扩散屏障以及调控种子萌发的作用[6-7]。角质层结构可分为三部分:第1部分是由嵌入细胞壁多糖的角质以及蜡质组成的角质层基层;第2部分是由角质和镶嵌在角质内部的蜡质共同组成的真角质层;第3部分是由蜡质膜/蜡质晶体沉积在植物表面形成的蜡质层[8]。

角质层由角质和蜡质组成,其中蜡质又分为表层蜡质和内部蜡质。角质层蜡质由超过20个碳原子的超长链脂肪酸(VLCFAs)及其衍生物组成,包括醛、烷烃、支链烷烃、烯烃、伯醇、仲醇、不饱和脂肪醇、酮和蜡酯,以及萜类和甾醇类的环状化合物等[9]。利用正向和反向的遗传学手段对拟南芥Arabidopsis thaliana等模式植物开展研究,目前蜡质的生物合成途径已经基本弄清。对拟南芥中大量蜡质合成缺陷突变体ECERIFERUM(CER)的研究,已经分离鉴定出了一大批涉及蜡质生物合成的蜡质突变体基因(CER)。质体合成的C16、C18脂肪酸是蜡质合成的重要前体物,在长链脂酰辅酶A合成酶(LACS)的作用下以脂酰-COA的形式运输到内质网,通过内质网上的脂肪酸延长酶复合体以及BAHD酰基转移酶CER2及其同系物CER2-LIKE1/ CER26和CER2-LIKE2在内的一些辅助因子的协同作用进行碳链延伸[10],生成C20以上的超长链脂酰-COA;随后通过烷烃合成途径形成醛、烷烃、次级醇和酮等蜡质组分,或通过内质网的醇合成途径形成初级醇和蜡酯等蜡质组分[11]。拟南芥烷烃合成酶CER1和WAX2/CER3基因突变体,其醛、烷烃、次级醇和酮的含量降低,这与烷烃合成通路的代谢产物一致;而CER1、WAX2/CER3和CYTB5共表达引起来自超长链脂酰-CoA的超长链烷烃的氧化还原依赖性合成,表明其可能编码烷烃合成途径中烷烃的合成[12]。作为拟南芥中编码醛脱羧酶的CER1基因家族成员之一的CER1-like1也通过与CER1相同的机制在烷烃的生物合成中起着至关重要的作用,但CER1-like1更偏向于催化短链烷烃的合成[13]。烷烃合成途径的最终反应被认为是由属于细胞色素P450家族的中链烷烃羟化酶1(MAH1/CYP96A15)催化烷烃氧化产生次级醇,并进一步催化次级醇氧化生成酮类[14]。研究表明:在醇合成途径中,编码脂酰辅酶A还原酶的CER4基因负责地上部分组织表皮细胞和根中初级醇的合成,而编码蜡酯合成酶基因的WSD1基因其拟南芥突变体表现出比野生型更低的蜡酯含量,表明WSD1可能负责蜡酯的合成[15-17]。

-

成熟角质层中还含有角质,角质是一种主要由ω端和中链羟基化的C16和C18的氧化脂肪酸以及甘油以酯键交联而成的聚合物[18]。角质单体的合成在内质网上进行,内质网对质体产生的C16和C18脂肪酸进一步修饰合成各种以单酰基甘油酯形式存在的角质单体。角质单体的合成涉及许多氧化反应,由细胞色素P450酶催化,其中末端碳链氧化反应涉及细胞色素P450末端羟化酶(CYP86A)家族成员,而中链氧化反应涉及细胞色素P450中链羟化酶(CYP77A)家族成员。拟南芥CYP86A2、CYP86A4、CYP86A7和CYP86A8突变体表现出角质层结构异常和角质组分改变,表明这几个基因与角质生物合成中ω链的羟基化密切相关[19]。ω-羟基脂肪酸则进一步经过脱氢反应生成脂肪醛,脂肪醛再经氧化反应最终生成二羧酸;虽然催化该过程的酶尚不清楚,但是由于CYP86A2和HTH(hothead)这2个基因的拟南芥突变体中缺少二羧酸,因此认为其可能涉及ω-OH脂肪酸氧化生成二羧酸的反应[20-21]。CYP77A6是目前唯一被鉴定为能够进行中链羟化的酶,CYP77A基因在花瓣中强烈表达,但在其拟南芥突变体的花瓣中却完全丢失了二羟基角质单体;其异源表达结果表明:该基因特异性催化ω-OH脂肪酸的中链羟基化,这也表明角质合成的中链羟基化反应发生在末端羟基化之后[22]。此外,CYP77A4异源表达催化环氧化羟基脂肪酸的合成,表明其可能参与环氧化脂肪酸的合成,但目前尚未完全证实。角质单体合成的最终反应由甘油-3-磷酸酰基转移酶(GPAT)催化完成,脂酰-COA在甘油-3-磷酸酰基转移酶(GPAT)催化下,酰基转移至甘油-3-磷酸生产单酰基甘油角质单体。拟南芥GPAT1-8基因被报道在细胞外脂质聚酯的合成中起着重要作用,其中GPAT4-8已经被证明有助于角质的合成,并且这几种酶相较于未被取代的脂肪酸表现出对末端羟基或羧基脂肪酸具有更强的催化效率,表明他们在氧化反应之后发挥作用[23]。

质膜ATP结合盒转运蛋白(ABCG)已经被证明可能与角质和蜡质向质外体的转运有关;而脂质转移蛋白(LTPs)被证明很可能有助于角质单体通过细胞壁向角质层的转运[24]。随着番茄Solanum lycopersicum中CD1/GDSL1这第1个角质合酶的发现,长久以来存疑的脂肪酶(GDSL)家族的酶在角质组装中的作用也得到了确证[25-27],而拟南芥α/β水解酶蛋白基因BODYGUARD (BDG)的发现证明了植物中可能存在一些其他的角质合酶[28]。尽管目前的研究已经在角质蜡质的合成、运输、组装方面取得了一定的进展,但角质层的形成机制仍然未知。

-

组成型抗性是植物的固有特性,是植物在遭受侵害前就己存在的抗性,包含植物固有的层和细胞壁的角质、蜡质、木质素等成分。其中,化学抗性主要包括酚类、皂苷、不饱和内酯及有机硫化合物等植保素(phytoalexins)[29]。组成型抗性是植物在长期的系统发育中产生和发展起来的[30],由植物基因型决定,但其抗性强弱也会受到环境因素的影响。

-

诱导型抗性是指植物经病原物刺激后诱导产生的抗性成分或抗性反应,包括物理抗性和化学抗性2类。物理抗性包括细胞壁及角质层加固和修复、乳突的形成、木质化作用及侵填体的形成等[31]。化学抗性则包括过敏性反应的诱导、植保素的产生、水解酶的激活及病程相关蛋白的表达等。诱导型抗性类似于免疫反应,只有在遇到外界因子,如物理损伤、植食者取食和病原菌侵染时才得以表现[32]。因此,诱导型抗性具有“开-关效应”,也称作“兼性抗性”。物理抗性与化学抗性通常协同发挥作用,一些物理屏障和化学因子不仅属于组成型抗性,也会在诱导型抗性中起重要作用,典型的如角质蜡质。

诱导型抗性并非植物的原始性状,而是一种衍生性状。植物长期处于复杂的环境中,容易受到各种病原物的侵害,组成型抗性是一种被动的防御机制,并不能确保植物对病原物的完全防御。为了更好地抵御病原菌的入侵,植物进化出了一系列诱导防御反应,植物的这种抵抗外界病原物刺激所形成的防御反应又被称为植物的先天免疫。植物先天免疫由微生物、病原体和/或损伤相关的分子模式(分别为MAMP,PAMP和/或DAMP)识别相应的化学分子所触发[33],这些化学分子在植物与微生物相互作用过程中释放,并被模式识别受体(pattern recognition receptors, PRRs)识别。

植物的先天免疫包括两大类,病原物相关分子模式触发型免疫(PAMP-triggered immunity,PTI)和效应因子触发型免疫(effector-triggered immunity,ETI)[34]。植物-病原体互作中植物启动先天免疫的第1步是植物模式识别受体(PRRs)识别病原相关分子模式(PAMPs)的化学分子,引发病原相关分子模式触发的免疫反应(PTI),激活植物体中促丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPK)信号通路,从而使植物产生早期应答反应[35]。然而,病原体为了抑制植物的诱导型防御反应便于自身的入侵反应,往往会产生大量抑制PTI激活的效应因子,而植物此时会启动先天免疫的第2步反应,通过特异性的抗性蛋白(R蛋白)识别效应因子,在侵染位点启动快速剧烈的防御反应,这种防御反应即为ETI[36]。ETI诱导的抗性通常表现为入侵位点的细胞凋亡,即过敏反应[37]。

MAMPs/PAMPs或DAMPs都可以诱导PTI[38],并且相较于特异性的ETI具有更加广谱的抗性反应,如活性氧(ROS)积累,激活MAPK依赖性信号级联反应,植物抗毒素的生物合成,水杨酸(SA)、茉莉酸(JA)和乙烯(ET)等防御相关激素以及相关抗性基因的诱导表达[33, 39]。植物的这2种免疫反应机制通过启动防御反应诱导植物产生局部和系统抗性,两者协同作用进而抵御病原菌的入侵[40]。植物在侵染位点启动超敏反应特异性抵御病原菌侵染的这种反应被称为植物的局部抗性,而与之相对的,植物活化抗性基因使植物在整株水平上产生抗性或者产生抵御病原菌再次入侵的抗性,这种非专化性的抗性则被称为系统抗性[41]。通常植物的系统抗性包括诱导系统抗性(ISR)和获得性系统抗性(SAR),ISR主要由非致病菌诱导产生,而SAR则是由植物响应病原菌侵染产生的[42]。这2种系统抗性依赖于SA,JA和ET信号途径的协同效应。SA和JA作为植物中十分重要的2条信号途径,在抗病化学信号的转导中的作用尤为重要。现在也有越来越多的证据表明,角质和蜡质在植物的诱导防御反应中也扮演着重要的角色[43]。

-

角质蜡质组成的角质层作为植物地上部分共有的一层保护性屏障,在植物组成型抗性中扮演着重要角色。角质蜡质组成型抗性作用也可分为物理抗性和化学抗性2类[44]。角质层及其组分角质蜡质维持着植物正常生长必需的机械强度,与植物对真菌的物理抗性密切相关;许多真菌需要通过附着胞的物理穿刺刺破植物角质层进而侵染内部细胞[45],因此,完整的具有一定机械强度的角质层会阻碍真菌对植物的侵染,如许多果腐病病原体只能通过角质层缺陷的方式侵染果实[46]。

植物角质蜡质组成对病原菌的物理抗性,不仅影响植物表皮机械强度,还会影响植物表面的疏水性(不渗透性)[44]。真菌孢子的萌发和细菌的繁殖需要高湿环境,疏水的角质层表面则不利于病原菌的停滞,能有效减少病原菌的侵染[47]。拟南芥和番茄角质蜡质合成缺陷的突变体具有强渗透性的角质层,表现出病原体感染的易感性。如拟南芥酰基载体蛋白4(ACP4)和GL1(GLABROUS 1)突变体的角质蜡质含量更低,增加了其表皮渗透性,叶片则表现出对2种病原体的高易感性[48-49]。研究表明:角质蜡质相关SHINE转录因子的突变导致角质层缺陷,进而导致了对灰霉病菌Botrytis cinerea易感性[50]。这些结果也进一步验证了角质蜡质代谢可通过调控角质层的渗透性进而影响植物的抗病性。

此外,角质蜡质组分也具有化学抗性功能。角质蜡质的某些组分可以抑制或者刺激孢子的萌发,如去蜡质处理的大麦Hordeum vulgare叶片有更多的附着胞生成,增加了其对锈菌的敏感性[51];水稻Oryza sativa叶片角质组分十六烷二醇,可以诱导稻瘟菌Pyricularia oryzae的产生和附着胞的分化形成,并促进灰霉病真菌孢子的萌发和角质酶的表达[52-53]。此外,角质和蜡质的某些组分对某些病原体还具有直接的抑制作用,如C16和C18羟基脂肪酸对丁香假单胞菌Pseudomonas syringae有直接的抑制作用[54],这些角质蜡质成分对病原菌的抑制作用构成了角质蜡质组成型抗性中的化学抗性。

综上所述,角质蜡质一方面能够通过影响角质层的物理性质(机械强度和疏水性),实现对病原菌的物理屏蔽作用;另一方面也能通过羟基脂肪酸等抑菌成分直接调控病原菌的增殖分化来实现其化学防御功能。

-

传统观点认为,角质层及其角质蜡质组分主要通过组成型抗性发挥其保护性屏障功能。现在更多研究证实:角质蜡质在植物的诱导防御反应中也发挥着重要作用[55]。与组成型抗性类似,角质蜡质的诱导型抗性也可分为物理抗性和化学抗性2类。在病原菌侵染植物的过程中,角质蜡质组分均会对病原菌的刺激作出响应。角质蜡质诱导型物理抗性功能的发挥,一般是响应病原菌的刺激,上调角质蜡质的合成,增强角质层的保护性屏障作用。如受到炭疽病菌Colletotrichum gloeosporioides感染的番茄果实,其角质蜡质的生物合成会显著上调[56]。柑橘Citrus sinensis花瓣感染炭疽病后,其表皮细胞脂质合成上调,角质蜡质相关代谢物沉积,并引起角质层结构的改变进而增强其物理抗性[57]。此外,大麦感染由禾谷镰刀菌Fusarium graminearum引起的赤霉病后,抗性品种小穗会上调角质层的生物合成进而增强其对病原菌的物理抗性[58]。上述这些都表明角质蜡质在植物的诱导防御反应中发挥了重要的物理屏障作用。

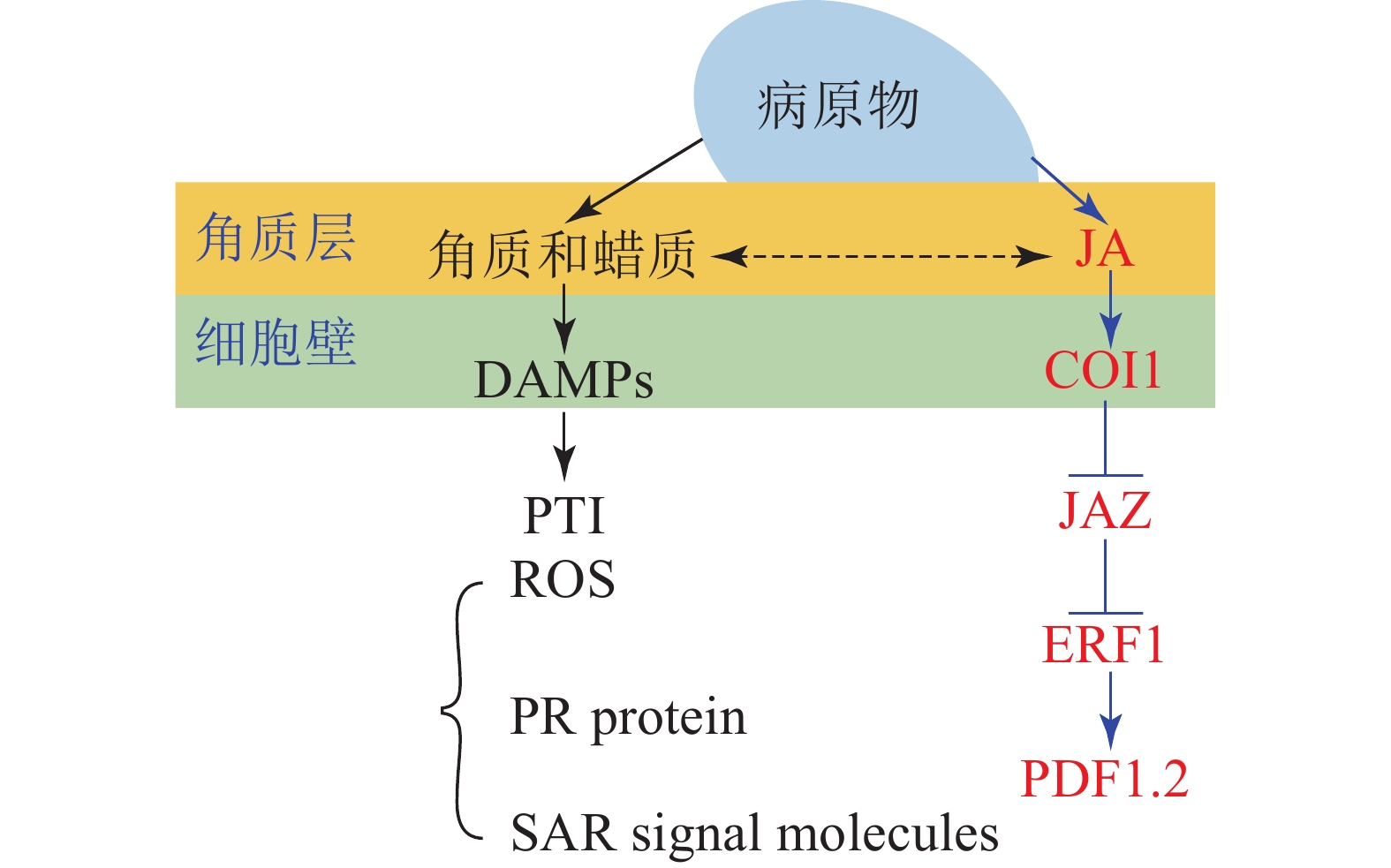

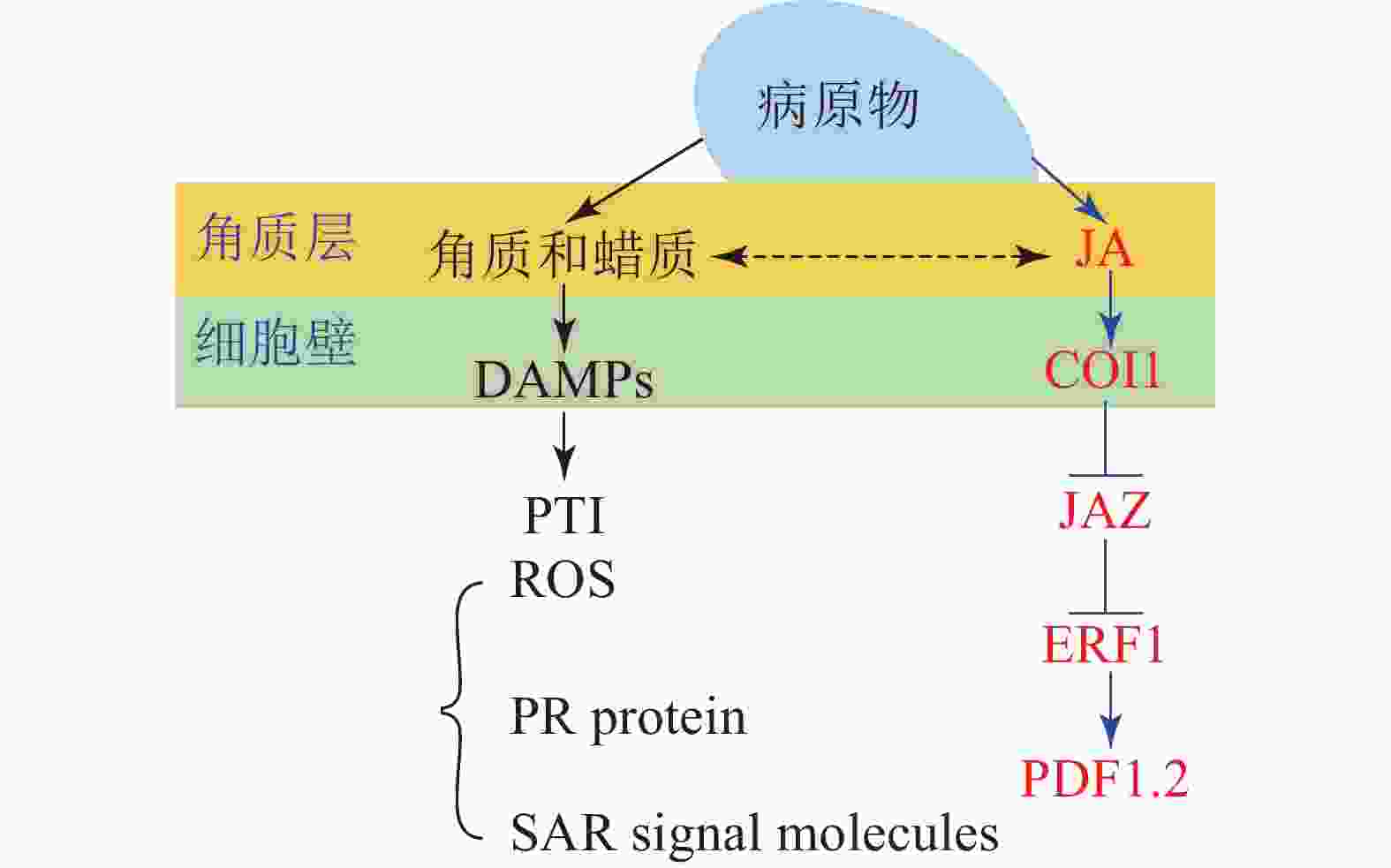

角质蜡质也可作为诱导型抗性成分在病原菌侵染过程中发挥化学抗性功能。病原体侵染植物后,植物产生的降解产物和释放的内生肽可作为植物损伤相关分子模式的诱导子(DAMPs)被植物模式识别受体(PRRs)所识别,继而启动下游的免疫反应(PTI)[33]。目前的研究表明:角质层被真菌角质酶降解的产物也可作为DAMPs被损伤相关模式的受体所识别[17, 59]。由此认为角质蜡质可以通过作为诱导子激活下游的诱导防御反应进而实现其化学抗性的功能(图1)。这一观点也得到了许多外施角质单体研究结果的支持,如外施无抑菌活性的角质单体增加了大麦对白粉病菌Erysiphe graminis f.sp. hordei的抗性[60];组织培养的马铃薯Solanum tuberosum细胞外施角质单体后乙烯的合成积累和相关防御基因的表达均上调[61];外源施加角质单体增加了番茄病程相关基因的表达水平[62];水稻叶片外源施加角质单体16-羟基棕榈酸,脂质转运蛋白基因OsLTP5和病程相关基因PR-10的表达也上调[63]。这些都在一定程度上表明角质蜡质可能是通过调控下游抗性基因的表达进而实现其化学抗性(图1)。

进一步的研究表明:除了作为诱导子调控下游抗性相关基因,某些角质蜡质组分也可以作为活性氧的诱导子诱导活性氧的积累。如黄瓜Cucumis sativus下胚轴外施角质蜡质组分的研究表明:某些角质蜡质成分具有良好的活性氧诱导活性[64-65],而活性氧介导了植物包括超敏反应在内的一系列防御反应。基于这些研究,目前也有一些观点认为:角质蜡质可能通过作为活性氧的诱导子来激活下游的诱导防御反应进而实现其抗性功能[43,66]。除此之外,角质蜡质被认为可能作为信号分子影响植物的系统获得性抗性(SAR)[67]。基于上述研究,可得出角质蜡质作为诱导子激活下游的诱导防御反应时,可能主要是通过调控病原物相关分子模式触发型免疫(PTI)中的包括活性氧爆发,抗病基因表达,系统获得性抗性在内的一系列的抗性反应进而实现其抗性功能(图1)。

大量研究证实:激素信号在植物-病原体互作中发挥了重要作用[68];激素作为重要的抗病信号可能涉及了植物角质蜡质介导的抗性反应。某些激素被证明可以调控角质蜡质的合成和相关抗性,如JA处理豌豆Vicia sativa幼苗,诱导其角质单体羟基脂肪酸的合成[69],而羟基脂肪酸作为植物的内源信号分子发挥了重要的抗性作用,这表明JA可以调控角质的生物合成进而介导其抗病性。JA和角质蜡质同属于脂肪酸代谢通路,具有共同的合成前体,因此,也有观点认为JA不仅能够直接调控角质蜡质的生物合成介导其抗病性,还和角质蜡质存在着代谢流的重定向;基于角质蜡质生物合成缺陷突变体的研究也在一定程度上支持了这一观点。如拟南芥突变体RST1角质蜡质生物合成缺陷,JA及其相关抗病基因PDF1.2上调表达,表现出对白粉病的抗性[70];柑橘自发突变体蜡质合成缺陷,JA和相关抗病基因PDF1.2上调表达,增加了对病原菌的抗性[71]。这些结果均表明:JA和角质蜡质之间可以通过代谢流的重定向进而调控植物的抗病性(图1)。

-

角质层作为植物抵御病原菌侵染的第1道防线,在植物-病原互作中具有重要作用。角质蜡质是角质层主要成分,一方面可以作为组成型抗性成分发挥物理抗性(物理屏障)和化学抗性(抑菌)作用;另一方面,也可作为诱导型抗性成分发挥作用,诱导产生的角质蜡质组分可作为信号分子或者诱导子激活下游的抗性反应进而发挥其化学抗性功能。目前,角质蜡质介导的诱导抗性研究受到广泛关注,但其作用机理尚未完全阐明;哪些角质蜡质组分参与了植物的诱导型防御反应,其作为诱导子激活下游抗性反应的具体机制如何?激素信号介导的角质蜡质抗性机制如何?诸多问题均有待深入探讨,角质蜡质抗性机理的阐释为作物抗性育种提供了新的思路。此外,虽然已有相关研究表明角质蜡质具有抑菌活性和植物免疫反应诱导子的作用,但目前尚无角质蜡质类生物农药(植物免疫诱导剂)的报道。因此,角质蜡质作为生物农药(植物免疫诱导剂)具有广阔的开发前景,同时角质蜡质类生物农药(植物免疫诱导剂)的开发也将为病害防控提供新的思路。

Metabolism of the cutin and wax of plants and their disease resistance mechanisms

-

摘要: 角质蜡质是植物在长期的生态适应过程中进化形成的一类次生代谢产物,广泛参与了植物抗逆、抵御病虫害侵染等诸多抗性生理过程。角质蜡质在植物-病原互作中发挥了重要作用,是植物抗病机制的重要组成部分。随着分子生物学的发展,人们对植物角质蜡质代谢及其抗病机理的认知不断深入。本研究综述了植物角质蜡质生物合成与其抗病机理的最新研究进展并对未来研究提出展望。目前,植物角质蜡质的抗性机理研究主要集中于组成型抗性和诱导型抗性2类。角质蜡质作为角质层主要成分,一方面可作为组成型抗性成分发挥物理抗性(物理屏障)和化学抗性(抑菌)作用;另一方面,也可作为诱导型抗性成分发挥作用,诱导产生的角质蜡质单体除了作为角质层主要成分发挥物理抗性外,也可作为信号分子或者诱导子激活下游的抗性反应进而发挥其化学抗性功能。未来可侧重于对角质蜡质诱导抗性机理的深入阐释,进一步丰富植物化学生态学研究理论体系。此外,基于角质蜡质的诱导抗性作用,可开发角质蜡质类生物农药(植物免疫诱导剂),为植物病害防控提供新思路。图1参71Abstract: As a type of secondary metabolites produced by plants during long-term ecological adaptation, cutin and wax are widely involved in many resistance physiological processes including stress defense and resistance to pests and diseases, playing critical roles in the plant-pathogen interaction, thus becoming an important part of plant disease resistance mechanism. With the development of molecular biology, there is an increasing understanding on the cutin and wax metabolism and their mechanisms against fungal disease in plant. With prior researches mainly focused on the constitutive resistance and inducible resistance of plant cutin and wax, the present study, with a review of the research progress achieved on the plant cutin and wax biosynthesis and its disease resistance mechanism, is aimed to put forward prospects for future research. It was concluded that (1) as the main components of the cuticle, the first line of defense for plants against pathogen infection, cutin and wax play a critical role in physical resistance (physical barrier) and chemical resistance (bacteriostasis) as constitutive resistance components, (2) They can also play the role of inducible resistance components and (3) in addition to being the main component of the cuticle to exert physical resistance, the inducible cutin and wax component can also act as a signal molecule or inducer to activate downstream resistance reactions and exert its chemical resistance function. In the future, the research concerning cutin and wax can be focused on an in-depth explanation of the mechanism of cutin and wax inducible resistance, so as to further enrich the theoretical system of plant chemical ecology. In addition, cutin and wax biopesticides (plant immunity inducers) can be developed based on the inducible resistance of cutin and wax to provide new insight for the plant diseases control. [Ch, 1 fig. 71 ref.]

-

Key words:

- cutin /

- wax /

- constitutive resistance /

- inducible resistance /

- review

-

[1] FRANCESCHI V R, PAAL K, ERIK C, et al. Anatomical and chemical defenses of conifer bark against bark beetles and other pests [J]. New Phytol, 2010, 167(2): 353 − 376. [2] RIEDERER M, MÜLLER C. Annual Plant Reviews Volume 23: Biology of the Plant Cuticle[M]. [s.l.]: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006: 1 − 10. [3] ARAG N W, REINA-PINTO J J, SERRANO M. The intimate talk between plants and microorganisms at the leaf surface [J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(19): 5339 − 5350. [4] ZIV C, ZHAO Zhenzhen, GAO Yug, et al. Multifunctional roles of plant cuticle during plant-pathogen interactions [J]. Front Plant Sci, 2018, 9(1): 1088. [5] LEE S B, SUH M C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species [J]. Plant Cell Rep, 2015, 34(4): 557 − 572. [6] BERHIN A, DE BELLIS D, FRANKE R B, et al. The root cap cuticle: a cell wall structure for seedling establishment and lateral root formation [J]. Cell, 2019, 176(6): 1367 − 1378. [7] INGRAM G, NAWRATH C. The roles of the cuticle in plant development: organ adhesions and beyond [J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(19): 5307 − 5321. [8] COHEN H, SZYMANSKI J, AHARONI A. Assimilation of ‘omics’ strategies to study the cuticle layer and suberin lamellae in plants [J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(19): 5389 − 5400. [9] JETTER R, KUNST L, SAMUELS A L. Composition of Plant Cuticular Waxes[M]. [s.l.]: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006: 145﹣181. [10] WANG Tianya, XING Jiewen, LIU Xinye, et al. GCN5 contributes to stem cuticular wax biosynthesis by histone acetylation of CER3 in Arabidopsis [J]. J Exp Bot, 2018, 69(12): 2911 − 2922. [11] KUNST L, SAMUELS L. Plant cuticles shine: advances in wax biosynthesis and export [J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2009, 12(6): 721 − 727. [12] BERNARD A, DOMERGUE F, PASCAL S, et al. Reconstitution of plant alkane biosynthesis in yeast demonstrates that Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 and ECERIFERUM3 are core components of a very-long-chain alkane synthesis complex [J]. Plant Cell, 2012, 24(7): 3106 − 3118. [13] PASCAL S, BERNARD A, DESLOUS P, et al. Arabidopsis CER1-LIKE1 functions in a cuticular very-long-chain Alkane-forming complex [J]. Plant Physiol, 2019, 179(2): 415 − 432. [14] GREER S, WEN Miao, BIRD D, et al. The cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP96A15 is the midchain alkane hydroxylase responsible for formation of secondary alcohols and ketones in stem cuticular wax of Arabidopsis [J]. Plant Physiol, 2007, 145(3): 653 − 667. [15] ROWLAND O, ZHENG H, HEPWORTH S R, et al. CER4 encodes an alcohol-forming fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase involved in cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis [J]. Plant Physiol, 2006, 142(3): 866 − 877. [16] LI Fengling, WU Xuemin, LAM P, et al. Identification of the wax ester synthase/acyl-coenzyme A: diacylglycerol acyltransferase WSD1 required for stem wax ester biosynthesis in Arabidopsis [J]. Plant Physiol, 2008, 148(1): 97 − 107. [17] YEATS T H, ROSE J K C. The formation and function of plant cuticles [J]. Plant Physiol, 2013, 163(1): 5 − 20. [18] SAMUELS L, KUNST L, JETTER R. Sealing plant surfaces: cuticular wax formation by epidermal cells [J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2008, 59(1): 683 − 707. [19] FICH E A, SEGERSON N A, ROSE J K C. The plant polyester cutin: biosynthesis, structure, and biological roles [J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2016, 67(1): 207 − 233. [20] KURDYUKOV S, FAUST A, TRENKAMP S, et al. Genetic and biochemical evidence for involvement of HOTHEAD in the biosynthesis of long-chain α-,ω-dicarboxylic fatty acids and formation of extracellular matrix [J]. Planta, 2006, 224(2): 315 − 329. [21] MOLINA I, B OHLROGGE J, POLLARD M. Deposition and localization of lipid polyester in developing seeds of Brassica napus and Arabidopsis thaliana [J]. Plant J, 2008, 53(1): 437 − 449. [22] LIBEISSON Y, POLLARD M, SAUVEPLANE V, et al. Nanoridges that characterize the surface morphology of flowers require the synthesis of cutin polyester [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(51): 22008 − 22013. [23] SINGER S D, CHEN G, MIETKIEWSKA E, et al. Arabidopsis GPAT9 contributes to synthesis of intracellular glycerolipids but not surface lipids[J]. J Exp Bot, 67(15): 4627 − 4638. [24] LI Nannan, XU Changcheng, LI-BEISSON Yonghua, et al. Fatty acid and lipid transport in plant cells [J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2016, 21(2): 145 − 158. [25] YEATS T H., HUANG Wenlin, CHATTERJEE S, et al. Tomato cutin deficient 1 (CD1) and putative orthologs comprise an ancient family of cutin synthase-like (CUS) proteins that are conserved among land plants [J]. Plant J Cell Mol Biol, 2014, 77(5): 667 − 675. [26] YEATS T H, MARTIN L B B, VIART H M-F, et al. The identification of cutin synthase: formation of the plant polyester cutin [J]. Nat Chem Biol, 2012, 8(7): 609 − 611. [27] GIRARD A L, MOUNET F, LEMAIRE-CLEMAIRE M, et al. Tomato GDSL1 is required for cutin deposition in the fruit cuticle [J]. Plant Cell, 2012, 24(7): 3119 − 3134. [28] GIRARD A L, MOUNET F, LEMAIRE-CHAMLEY M L J, et al. BODYGUARD is required for the biosynthesis of cutin in Arabidopsis [J]. New Phytol, 2016, 211(2): 614 − 626. [29] 宗兆峰, 康振生. 植物病理学原理[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2002. [30] ANNE K, MARTIN S D, THOMAS C, et al. Tradeoffs associated with constitutive and induced plant resistance against herbivory [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2011, 108(14): 5685 − 5689. [31] ALIETA E, PIERLUIGI B, REBECCA G, et al. Induced resistance to pests and pathogens in trees [J]. New Phytol, 2010, 185(4): 893 − 908. [32] AGRAWAL A A. Induced responses to herbivory and increased plant performance [J]. Science, 1998, 279(5354): 1201 − 1202. [33] BOLLER T, FELIX G. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors [J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2009, 60(1): 379 − 406. [34] ZIPFEL C. Plant pattern-recognition receptors [J]. Trends Immunol, 2014, 35(7): 345 − 351. [35] CONRATH U, BECKERS G J, LANGENBACH C J, et al. Priming for enhanced defense [J]. Annu Rev Phytopathol, 2015, 53(1): 97 − 119. [36] SPOEL S H, DONG Xinnian. How do plants achieve immunity? defence without specialized immune cells [J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2012, 12(2): 89 − 100. [37] GRAY W M. Plant defence: a new weapon in the arsenal [J]. Curr Biol, 2002, 12(10): R352 − R354. [38] YU Xiao, FENG Baomin, HE Ping, et al. From chaos to harmony: responses and signaling upon microbial pattern recognition [J]. Annu Rev Phytopathol, 2017, 55(1): 109 − 137. [39] HETMANN A, KOWALCZYK S. Membrane receptors recognizing MAMP/PAMP and DAMP molecules that activate first line of defence in plant immune system [J]. Postepy Biochem, 2018, 64(1): 29 − 45. [40] TSUDA K, SOMSSICH I E. Transcriptional networks in plant immunity [J]. New Phytol, 2015, 206(3): 932 − 947. [41] DURRANT W E, X D. Systemic acquired resistance [J]. Annu Rev Phytopathol, 2006, 1(4): 179 − 184. [42] KACHROO A, ROBIN G P. Systemic signaling during plant defense [J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2013, 16(4): 527 − 533. [43] REINA-PINTO J J, YEPHREMOV A. Surface lipids and plant defenses [J]. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2009, 47(6): 540 − 549. [44] KHANAL B P, KNOCHE M. Mechanical properties of cuticles and their primary determinants [J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(19): 5351 − 5367. [45] RYDER L S, TALBOT N J. Regulation of appressorium development in pathogenic fungi [J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2015, 26(1): 8 − 13. [46] GUAN Yeqing, CHANG Ruifeng, LIU Guojian. Role of lenticels and microcracks on susceptibility of apple fruit to Botryosphaeria dothidea [J]. Eur J Plant Pathol, 2015, 143(2): 317 − 330. [47] 李婧婧, 黄俊华, 谢树成. 植物蜡质及其与环境的关系[J]. 生态学报, 2011, 31(2): 565 − 574. LI Jingjing, HUANG Junhua, XIE Shucheng. Plant wax and its response to environmental conditions: an overview [J]. Acta Ecol Sin, 2011, 31(2): 565 − 574. [48] YE Xia, YU Keshun, GAO Qingming, et al. Acyl CoA binding proteins are required for cuticle formation and plant responses to microbes [J]. Front Plant Sci, 2012, 3: 224. [49] YE Xia, YU Keshun, NAVARRE D, et al. The glabra1 mutation affects cuticle formation and plant responses to microbes [J]. Plant Physiol, 2010, 154(2): 833 − 846. [50] SELA D, BUXDORF K, SHI J X, et al. Overexpression of AtSHN1/WIN1 provokes unique defense responses[J]. Plos One, 2013, 8(7): e70146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070146. [51] RUBIALES D, NIKS R E. Avoidance of rust infection by some genotypes of Hordeum chilense due to their relative inability to induce the formation of appressoria [J]. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol, 1996, 49(2): 89 − 101. [52] GILBERT R D, JOHNSON A M, DEAN R A. Chemical signals responsible for appressorium formation in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea [J]. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol, 1996, 48(5): 335 − 346. [53] LEROCH M, KLEBER A, SILVA E, et al. Transcriptome profiling of Botrytis cinerea conidial germination reveals upregulation of infection-related genes during the prepenetration stage [J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2013, 12(4): 614 − 626. [54] XIAO Fangming, GOODWIN S M, XIAO Yanmei, et al. Arabidopsis CYP86A2 represses Pseudomonas syringae type Ⅲgenes and is required for cuticle development [J]. Embo J, 2014, 23(14): 2903 − 2913. [55] KACHROO A, KACHROO P. Fatty acid-derived signals in plant defense [J]. Annu Rev Phytopathol, 2009, 47: 153 − 176. [56] NOAM A, GILGI F, DANA M, et al. Simultaneous transcriptome analysis of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and tomato fruit pathosystem reveals novel fungal pathogenicity and fruit defense strategies [J]. New Phytol, 2015, 205(2): 801 − 815. [57] MARQUES J P R, AMORIM L, SP SITO M B, et al. Ultrastructural changes in the epidermis of petals of the sweet orange infected by Colletotrichum acutatum [J]. Protoplasma, 2015, 253(5): 1 − 10. [58] KUMAR A, YOGENDRA K N, KARRE S, et al. WAX INDUCER1 (HvWIN1) transcription factor regulates free fatty acid biosynthetic genes to reinforce cuticle to resist Fusarium head blight in barley spikelets [J]. J Exp Bot, 2016, 67(14): 4127 − 4139. [59] ZHAO Chunzhao, NIE Haozhen, SHEN Qiujing, et al. EDR1 physically interacts with MKK4/MKK5 and negatively regulates a MAP kinase cascade to modulate plant innate immunity [J]. PLoS Genet, 2014, 10(5): e1004389. [60] SCHWEIZER P, JEANGUENAT A, WHITACRE D, et al. Induction of resistance in barley against Erysiphe graminis f.sp. hordei by free cutin monomers [J]. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol, 1996, 49(2): 103 − 120. [61] SCHWEIZER P, FELIX G, BUCHALA A, et al. Perception of free cutin monomers by plant cells [J]. Plant J, 2010, 10(2): 331 − 341. [62] BUXDORF K, RUBINSKY G, BARDA O, et al. The transcription factor SlSHINE3 modulates defense responses in tomato plants [J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2014, 84(1/2): 37 − 47. [63] KIM T H, PARK J H, KIM M C, et al. Cutin monomer induces expression of the rice OsLTP5 lipid transfer protein gene [J]. J Plant Physiol, 2008, 165(3): 345 − 349. [64] KAUSS H, FAUTH M, JEBLICK M W. Cucumber hypocotyls respond to cutin monomers via both an inducible and a constitutive H2O2-generating system [J]. Plant Physiol, 1999, 120(4): 1175 − 1182. [65] FAUTH M, SCHWEIZER P, BUCHALA A, et al. Cutin monomers and surface wax constituents elicit H2O2 in conditioned cucumber hypocotyl segments and enhance the activity of other H2O2 elicitors [J]. Plant Physiol, 1998, 117(4): 1373 − 1380. [66] SERRANO M, COLUCCIA F, TORRES M, et al. The cuticle and plant defense to pathogens [J]. Front Plant Sci, 2014, 5: 274. [67] XIA Ye, GAO Qingming, YU Keshun, et al. An intact cuticle in distal tissues is essential for the induction of systemic acquired resistance in plants [J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2009, 5(2): 151 − 165. [68] DENANC N S, NCHEZ-VALLET A, GOFFNER D, et al. Disease resistance or growth: the role of plant hormones in balancing immune responses and fitness costs [J]. Front Plant Sci, 2013, 4: 155. [69] PINOT F, BENVENISTE I, SALAN J P, et al. Methyl jasmonate induces lauric acid omega-hydroxylase activity and accumulation of CYP94A1 transcripts but does not affect epoxide hydrolase activities in Vicia sativa seedlings [J]. Plant Physiol, 1998, 118(4): 1481 − 1486. [70] MANG H G, LALUK K A, PARSONS E P, et al. The Arabidopsis RESURRECTION1 gene regulates a novel antagonistic interaction in plant defense to biotrophs and necrotrophs [J]. Plant Physiol, 2009, 151(1): 290 − 305. [71] HE Yizhong, HAN Jingwen, LIU Runsheng, et al. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of a wax deficient citrus mutant exhibiting jasmonic acid-mediated defense against fungal pathogens [J]. Hortic Res, 2018, 5(1): 43 − 43. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20190745

下载:

下载: