-

氧化亚氮(N2O)是一种长效温室气体,其增温潜势约为二氧化碳(CO2)的298倍[1-2],对全球气候变暖具有较大的推动作用[3-4]。同时,大气中N2O浓度的上升对臭氧层造成显著的破坏,并且对生态环境也产生一系列的负面影响[5]。土壤是N2O的主要排放源,其排放量约占总排放量的70%[6]。因此,在土壤N2O排放日趋严重的背景下,研发土壤N2O减排技术是当前亟待解决的热点问题[7-8]。

生物质炭(biochar)是生物质在限氧或无氧环境中通过高温裂解而成的一类具有强吸附性,化学结构稳定且富含碳素的芳香态化合物[9]。生物质炭施用可以显著改善土壤性质,并在土壤N2O减排方面具有巨大潜力[10-11]。然而,生物质炭所含的矿质养分数量和类型较为匮乏,难以满足植物生长所需的营养需求。传统化肥的施用,可为植物生长提供养分,但却增加了土壤N2O的排放[12]。生物质炭基肥是一种新型肥料,可在改善土壤理化性质的同时,提供充足的养分,有效地弥补生物质炭速效养分不足的问题[11,13]。然而,与传统化肥相比,施用生物质炭基肥到底是促进还是抑制土壤N2O排放,尚不明确。此外,生物质炭基肥的施用会显著影响土壤的理化和微生物学性质,而上述性质的改变对土壤N2O排放的影响机制未有定论。

毛竹Phyllostachys edulis是中国亚热带地区重要的森林资源,其种植面积已超过400万hm2,约占竹类面积的72%[14]。毛竹能在短期内快速增加植被碳储量,因此,在碳汇功能方面具有独特的优势[15-18]。毛竹的生长对氮素养分的需求量较大。尿素的施用,一方面可以促进毛竹的生长,从而增加毛竹林的固碳量,但另一方面却增加了毛竹林土壤的N2O排放[19-22]。生物质炭基肥具有提供有效养分与减少温室气体排放的双重功效,但生物质炭基肥对毛竹林土壤N2O通量的影响机制尚不明确。基于此,本试验以亚热带地区毛竹林为研究对象,比较研究了生物质炭基尿素(以下称炭基尿素)和普通尿素(以下称尿素)施用对毛竹林土壤N2O通量、土壤温度、含水量、不同氮组分以及脲酶活性和蛋白酶活性的影响,分析土壤N2O通量与上述土壤环境因子之间的关系,旨在为研发森林土壤N2O减排的施肥技术提供参考。

-

试验样地位于杭州市临安区青山镇亚热带典型毛竹林示范样地(30°13′N, 119°47′E)。该区域的年均气温为15.9 ℃,年均降水量为1420 mm。试验区的土壤类型为红壤,基本理化性质如下:土壤容重为1.14 g·cm−3,砂粒为48.7%,粉粒为33.1%,黏粒为18.2%,pH 为4.87,有机碳为18.2 g·kg−1,全氮为1.76 g·kg−1,碱解氮为106.9 mg·kg−1,有效磷为7.64 mg·kg−1,速效钾为90.5 mg·kg−1。

-

试验地毛竹林由常绿阔叶林于2006年转化而来,其平均胸径9.8 cm,密度3 000株·hm−2。在该区域布置试验处理小区。试验包含5个处理:①对照(不施肥,ck);②低水平尿素(100 kg·hm−2,LU);③高水平尿素(300 kg·hm−2,HU);④低水平炭基尿素(100 kg·hm−2,LBU);⑤高水平炭基尿素(300 kg·hm−2,HBU)。随机区组设计(小区面积为120 m2),重复3次。本试验中,炭基尿素制备流程为:将水稻Oryza sativa秸秆生物质炭(<2 mm)以一定比例与尿素进行粉碎处理,放置造粒机中完成造粒,最后烘干至恒量。炭基尿素肥料中氮和碳的质量分数分别为32%和10%;用于制备炭基尿素的生物质炭的碳和氮的质量分数分别为5.8和569 g·kg−2。每个小区中心放置1个静态箱底座,分别在试验处理后的第1、7、28天采样气体和土壤样品,之后每月采样1次。采集的土壤样品用来测定土壤含水量、铵态氮(NH4 +-N)、硝态氮(NO3 –-N)、水溶性有机氮(WSON)、微生物量氮(MBN)、脲酶活性和蛋白酶活性。

-

本试验采用静态箱-气相色谱法测定土壤N2O排放通量[23]。采集气体时间为9:00—11:00。使用注射器在0、10、20和30 min进行气体采集,随后注入真空气袋。在采集气体的同时,测定静态箱内温度和土壤表层5 cm处温度。气袋中N2O体积分数使用岛津GC-2014气相色谱仪测定。土壤N2O通量的计算如下[23-24]:

式(1)中:F为N2O(μg·m−2·h−1)的排放通量;ρ为标准状况下N2O气体的密度(mg·m−3);V为静态箱体积(m3);A为静态箱底部区域面积(m2);T0和P0分别为标准状态下的绝对温度和气压;

$\dfrac{\mathrm{d} C_{t}}{\mathrm{~d} t}$ 为单位时间内取样箱内N2O气体体积分数的变化(m3·m−3·h−1),t为取样时静态箱密闭时间(h),Ct为该段时间内N2O气体体积分数变化值(m3·m−3);T和P分别表示测定箱内的绝对温度(K)和大气压(Pa)。土壤N2O累积排放通量的计算公式如下:式(2)中:Mg为N2O累积排放通量(kg·hm−2·a−1),R为土壤N2O通量(μg·m−2·h−1),i为采样次数,t为采样时间,n为总测定次数,ti+1−ti为2次采样的间隔天数[23-24]。

-

在试验处理前,对样地表层土壤(0~20 cm)进行取样并测定相关指标。土壤含水量采用烘干法测定,有机碳和全氮质量分数使用元素分析仪测定,有效磷质量分数采用钼锑抗显色法[25]测定,速效钾质量分数采用火焰光度法测定[26],碱解氮质量分数采用碱解扩散法测定[27]。在气体采样结束后立即采集土壤样品并进行分析测定。土壤WSON质量分数测定采用LI等[28]的方法测定,土壤MBN采用氯仿熏蒸-硫酸钾浸提法测定[29],NH4 +-N和NO3 –-N质量分数测定参照ZHOU等[30]的方法测定。土壤脲酶活性用靛酚蓝比色法[31]测定,蛋白酶活性的分析参照GREENFIELD等[32]的方法。

-

数据处理与统计分析应用SPSS 23.0软件进行。应用重复测量方差分析确定试验处理、时间以及试验处理与时间的交互作用对土壤N2O通量的影响,应用单因素方差分析结合最小显著性差异法,分析试验处理对土壤N2O年均排放速率、年累积排放量以及其他土壤环境因子年均值的影响。应用一元线性回归方程,分析土壤N2O通量与土壤温度、含水量、氮组分、脲酶活性和蛋白酶活性之间的相关性。

-

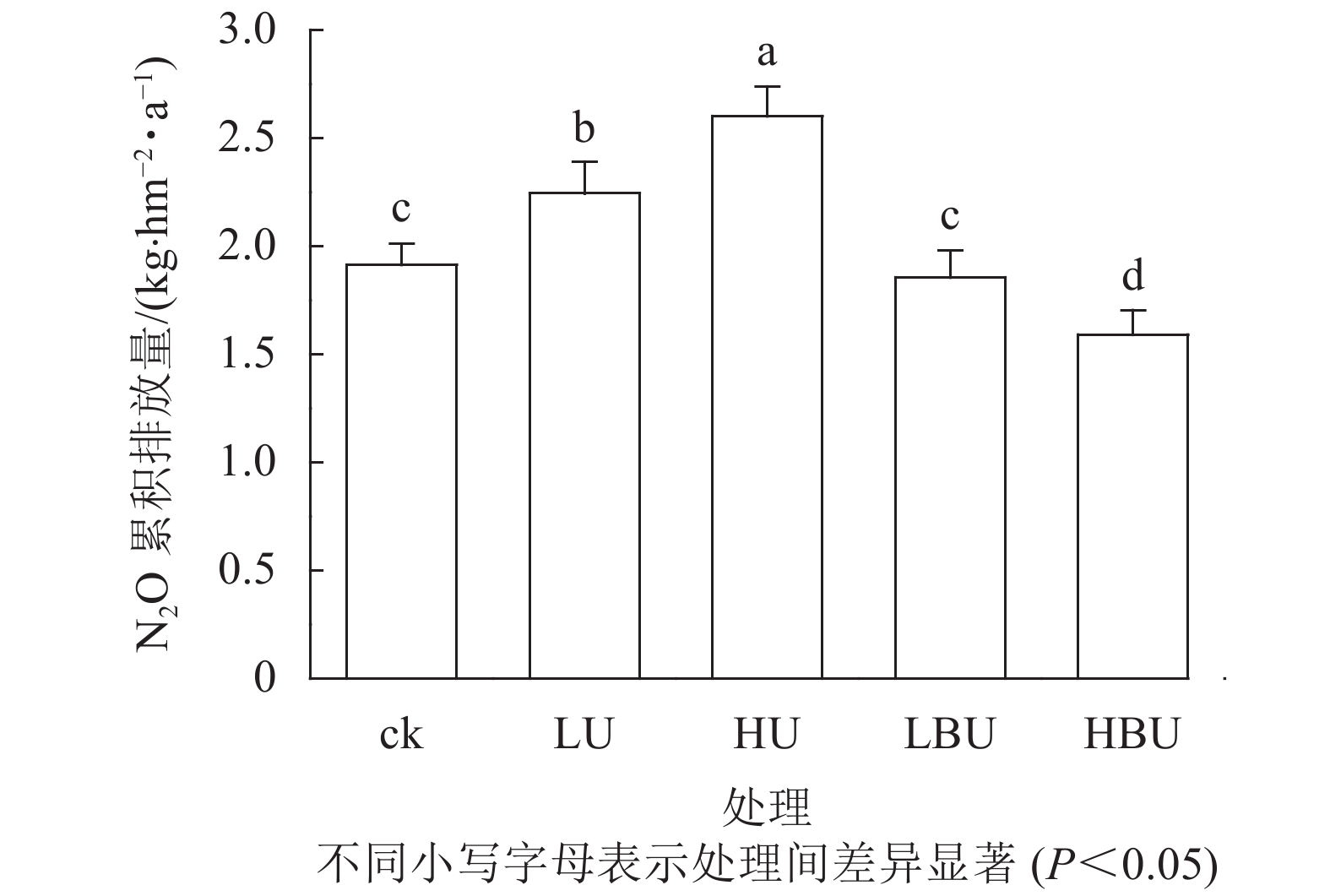

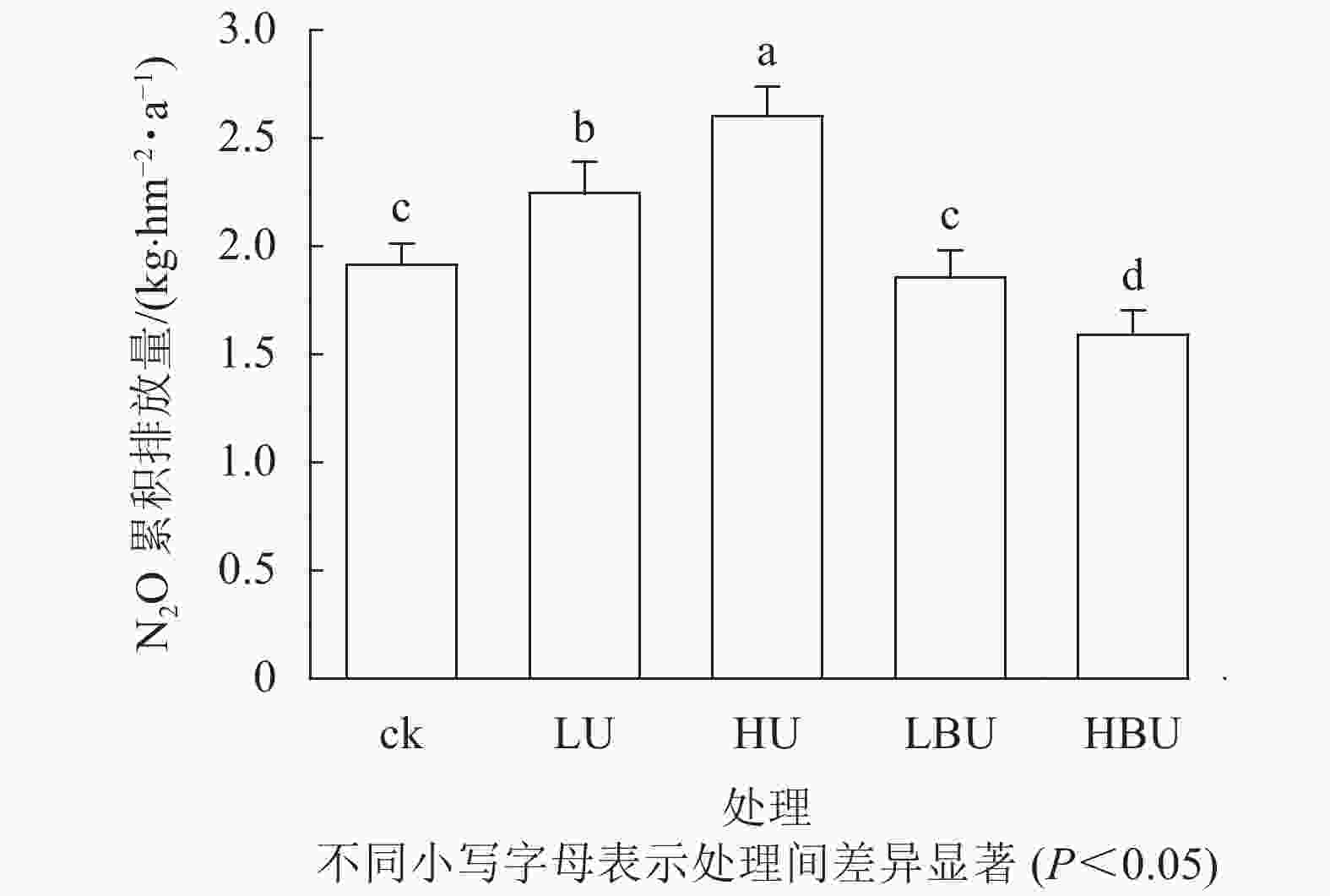

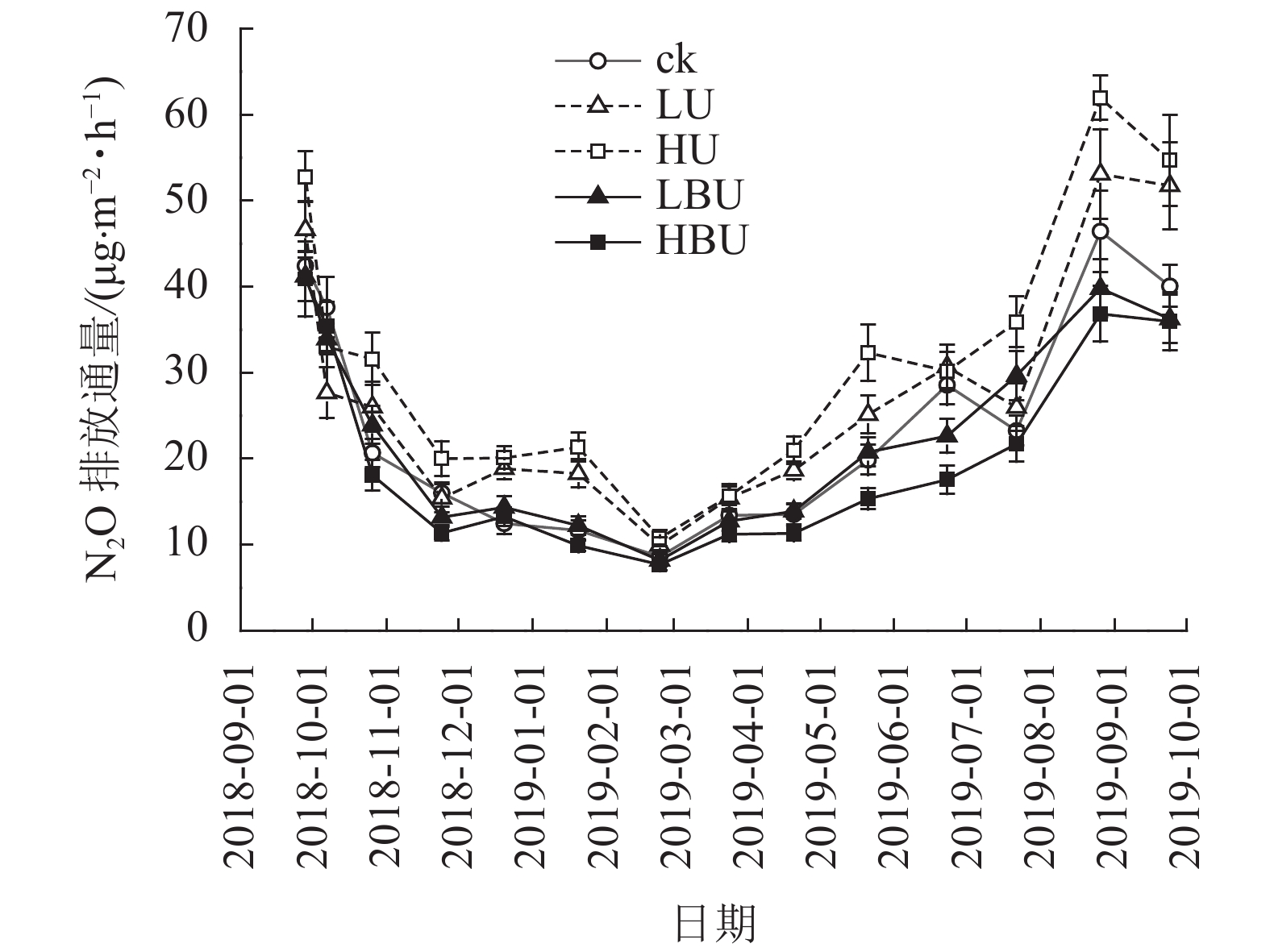

由表1可知:试验处理、处理后时间及两者交互作用对N2O具有极显著影响(P<0.01)。在ck、LU、HU、LBU、HBU处理下,土壤N2O通量具有相似的季节变化规律(图1)。总体来看,土壤N2O排放通量在7—9月最大,在1—2月最小。毛竹林土壤N2O排放通量在尿素处理下显著增加,且随尿素用量增加而增加。然而,炭基尿素处理使毛竹林土壤N2O排放通量显著降低,其降低幅度随炭基尿素用量增加而增强。与ck相比,LU、HU处理使毛竹林土壤N2O的年均排放通量增加14.6%和31.9%;而LBU、HBU处理使毛竹林土壤N2O的年均排放通量降低了3.51%和14.4%(图2)。

项目 土壤温度 土壤含水量 NH4 +-N NO3 −-N WSON MBN 脲酶 蛋白酶 N2O 处理 ns ns ** ** ** ns ** ** ** 处理后时间 ** ** ** ** ** ** ** ** ** 处理×处理后时间 ** * ** ** ** ** ** ** ** 说明:ns表示影响不显著; *表示影响显著(P<0.05); **表示影响极显著(P<0.01) Table 1. Repeated measures ANOVA for the effects of different fertilization treatments on nine response variables

Figure 2. Biochar-based urea and common urea effects on annual cumulative soil N2O effluxes in a Ph. edulis forest

如图2所示:毛竹林土壤N2O年累积排放量在尿素处理下显著增加,且随尿素用量增加而增加。然而,炭基尿素处理降低了毛竹林土壤N2O年累积排放量。相比于ck,低水平和高水平尿素处理导致土壤N2O年累积排放通量分别提高了17.3%和36.0%,低水平和高水平炭基尿素处理导致土壤N2O年累积排放通量分别减少了3.1%和16.9%。

-

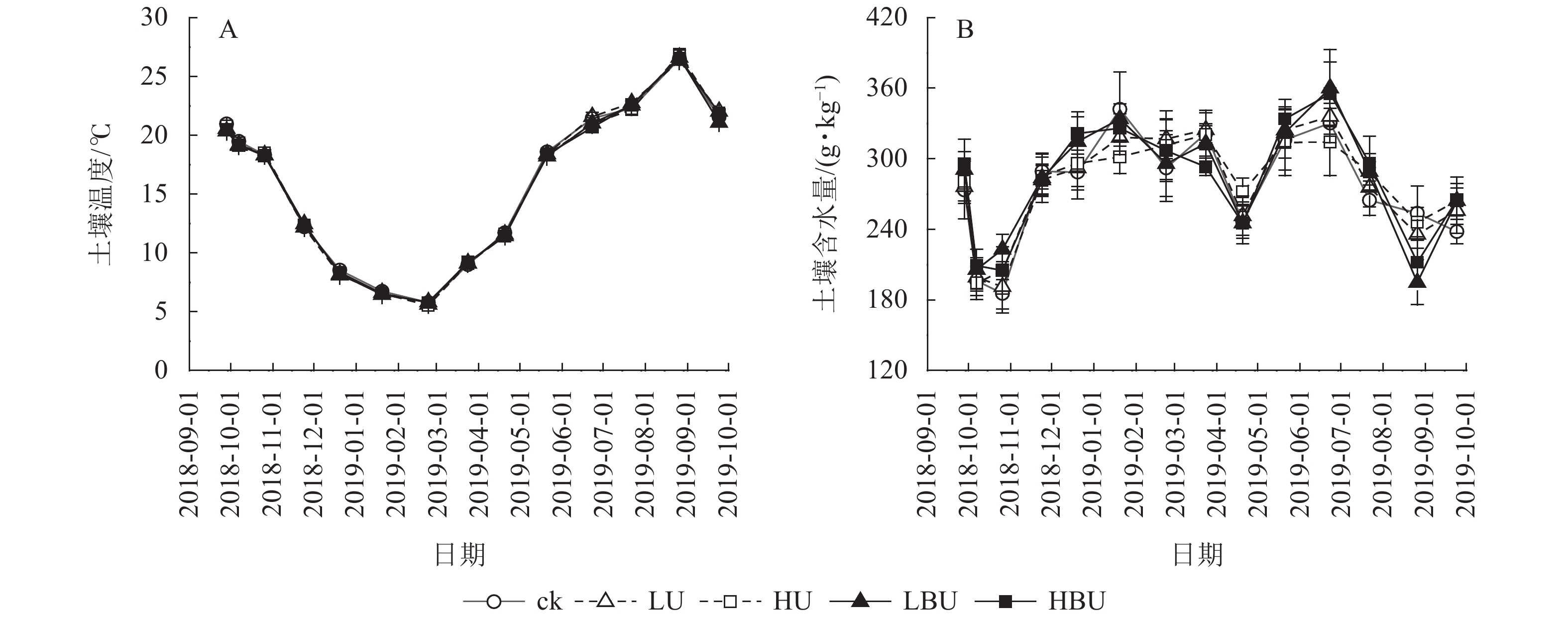

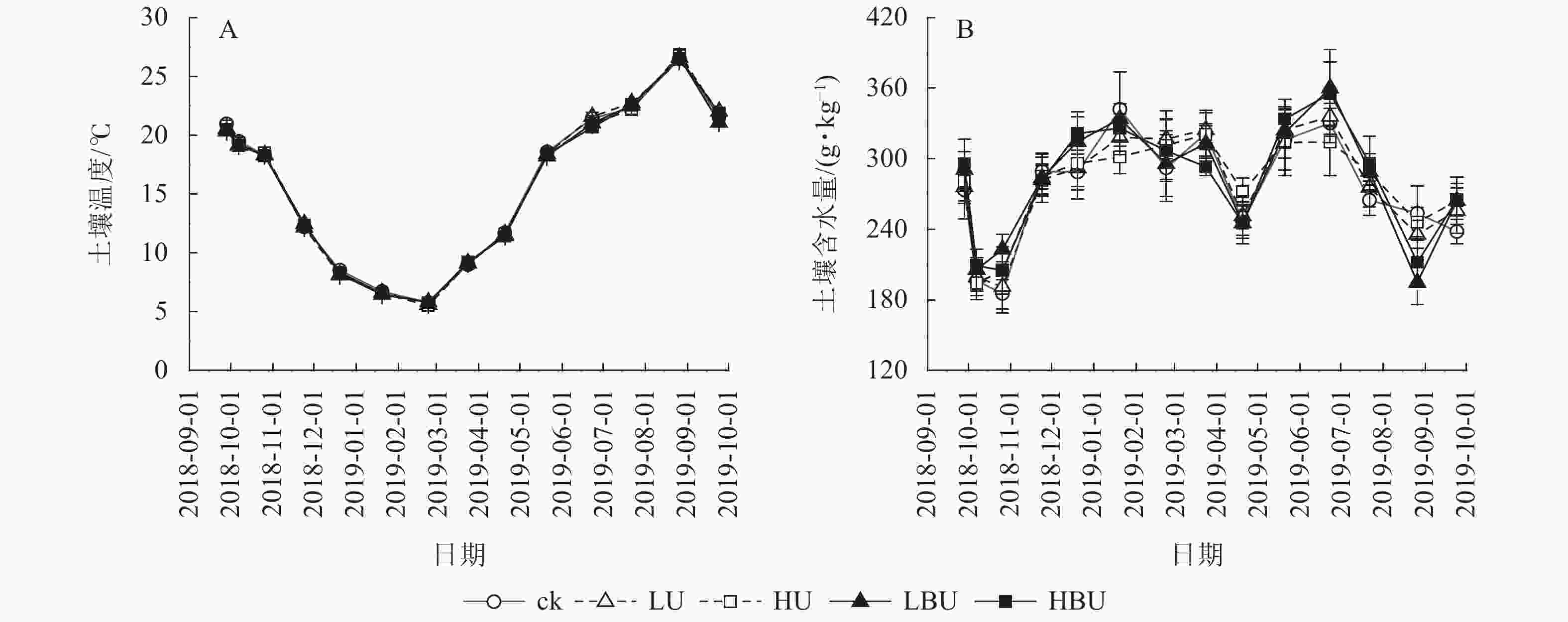

由表1可知:试验处理与处理后时间的交互作用对土壤含水量有显著影响(P<0.05),对土壤温度和MBN均具有极显著影响(P<0.01);试验处理、处理后时间及两者交互作用对土壤NH4 +-N、NO3 –-N和WSON质量分数以及脲酶和蛋白酶活性的影响达到极显著水平(P<0.01)。在本试验5种处理下,毛竹林土壤温度均具有显著的季节性变化特征(图3A)。7—9月土壤温度最高,1—2月最低,但不同处理间土壤温度无显著性差异。由图3B可见:在ck、LU、HU、LBU、HBU处理下,土壤含水量年均值分别为282.2、284.7、286.9、289.9和287.4 g·kg−1。与ck相比,施肥处理对土壤含水量年均值无显著影响(表1)。

Figure 3. Biochar-based urea and common urea effects on soil temperature and moisture content in a Ph. edulis forest

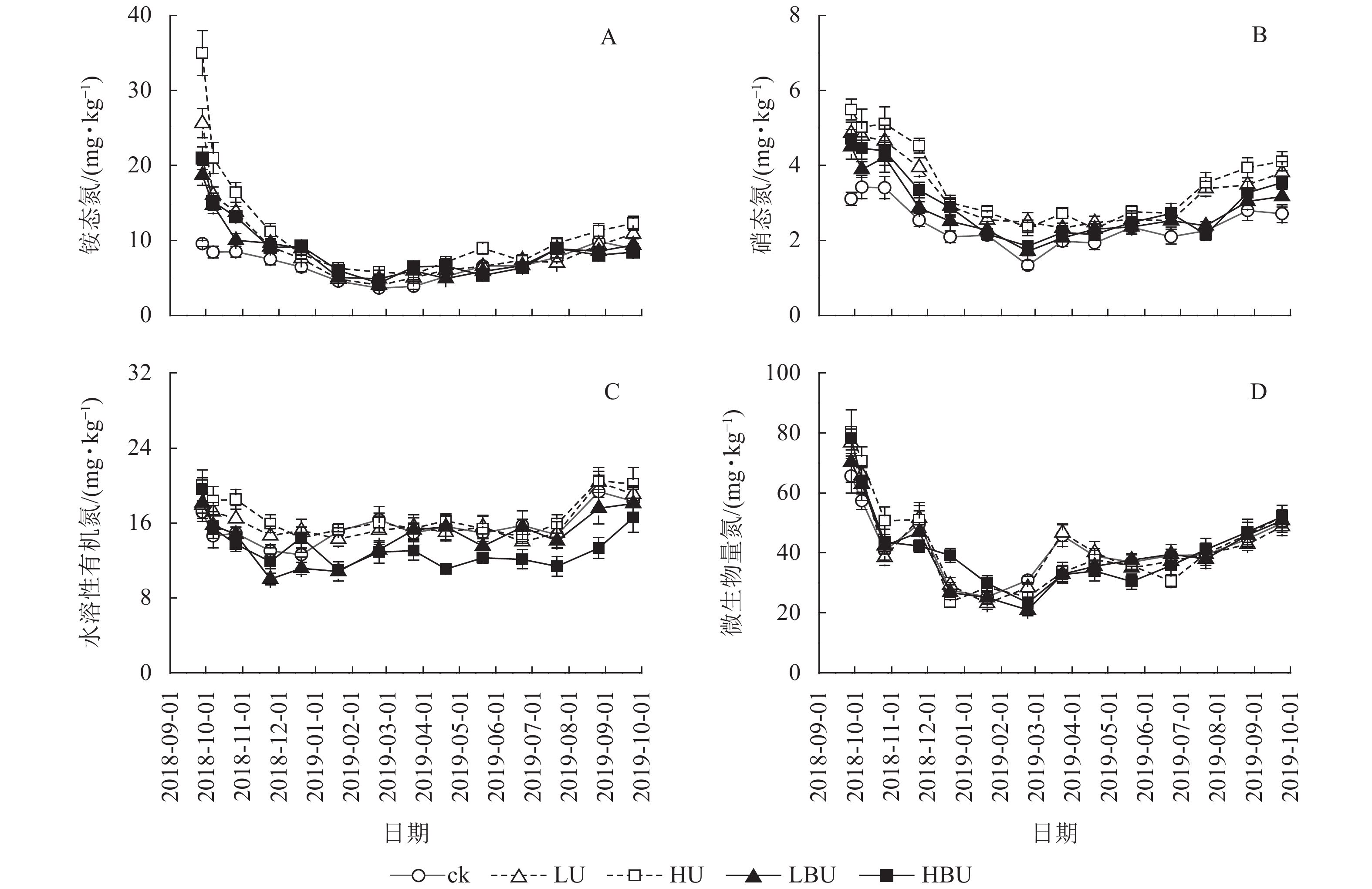

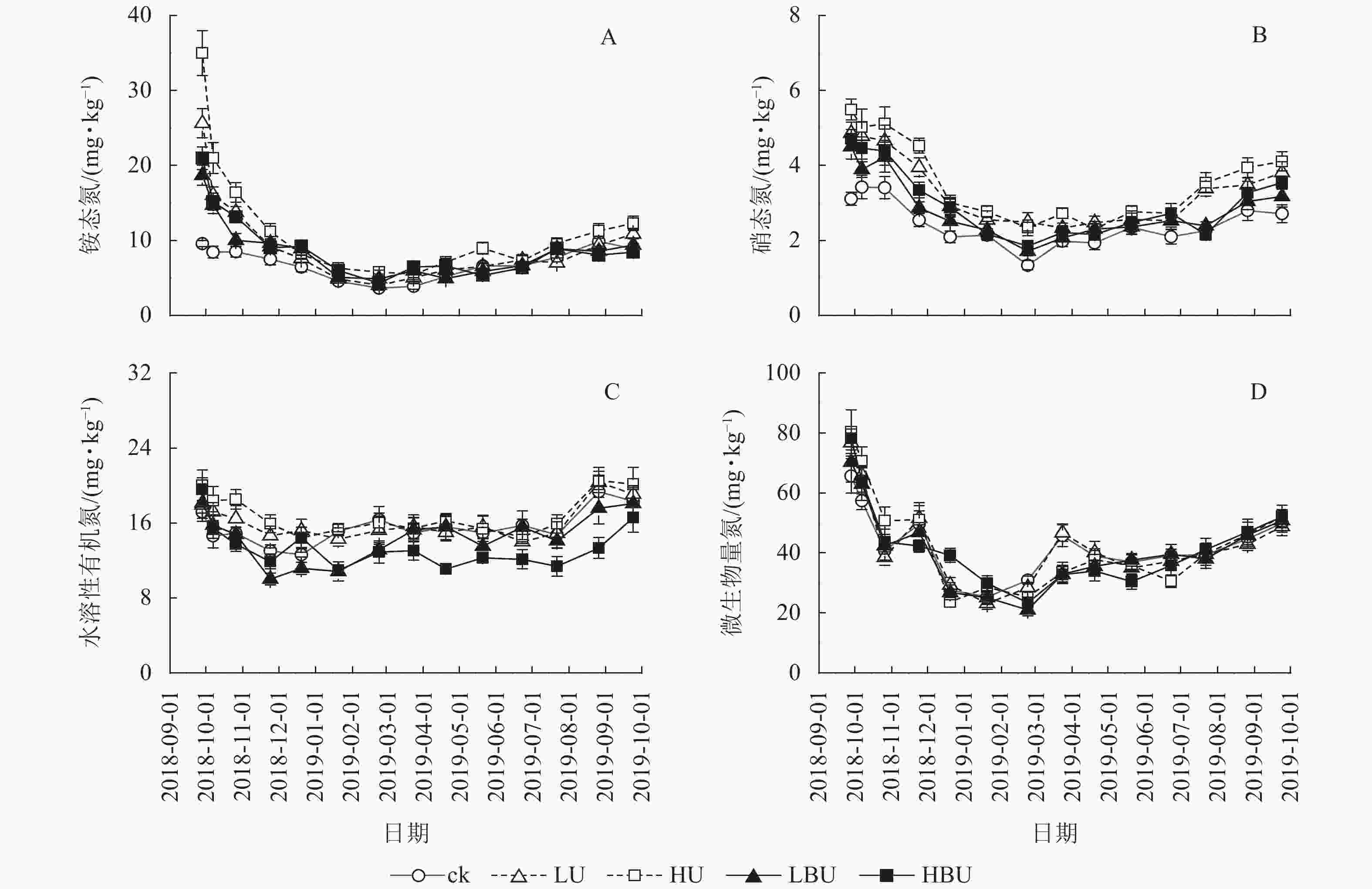

与ck相比,LU、HU、LBU和HBU处理下毛竹林土壤NH4 +-N质量分数年均值分别增加了36.9%、70.2%、18.5%和27.3%;使土壤NO3 –-N质量分数年均值分别增加了44.3%、53.6%、26.4%和17.6%(图4,表2)。与ck相比,LU、HU处理使毛竹林土壤WSON质量分数分别增加了3.3%和15.2%,而LBU、HBU处理使毛竹林土壤WSON含量分别降低了6.4%和13.2%(表2)。另外,炭基尿素和尿素处理均对土壤MBN质量分数无显著影响(表2)。

Figure 4. Biochar-based urea and common urea effects on different soil N fractions in a Ph. edulis forest

处理 NH4 +-N/

(mg·kg−1)NO3 −-N/

(mg·kg−1)WSON/

(mg·kg−1)MBN/

(mg·kg−1)脲酶/

(μmol·g−1·h−1)蛋白酶/

(μmol·g−1·h−1)ck 6.96 d 2.44 e 15.5 b 42.3 ab 1.15 b 0.88 c LU 9.52 b 3.34 b 16.1 b 43.1 a 1.28 a 0.97 b HU 11.84 a 3.60 a 16.9 a 43.3 a 1.33 a 1.03 a LBU 8.72 c 2.85 d 14.5 c 41.1 b 1.11 b 0.86 d HBU 9.14 bc 3.02 c 13.5 d 42.4 ab 1.00 c 0.77 e 说明:不同小写字母表示处理间差异显著(P<0.05) Table 2. Biochar-based urea and common urea effects on annual mean value of soil environmental factors in a Ph. edulis forest

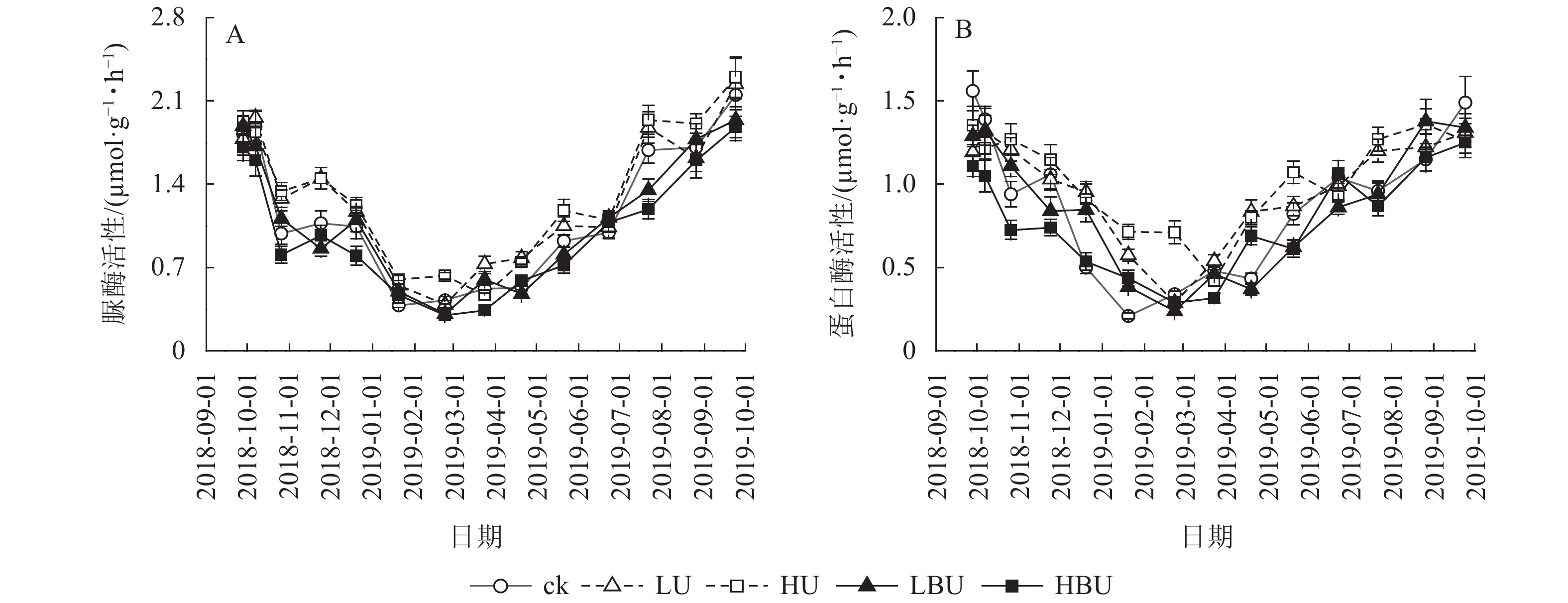

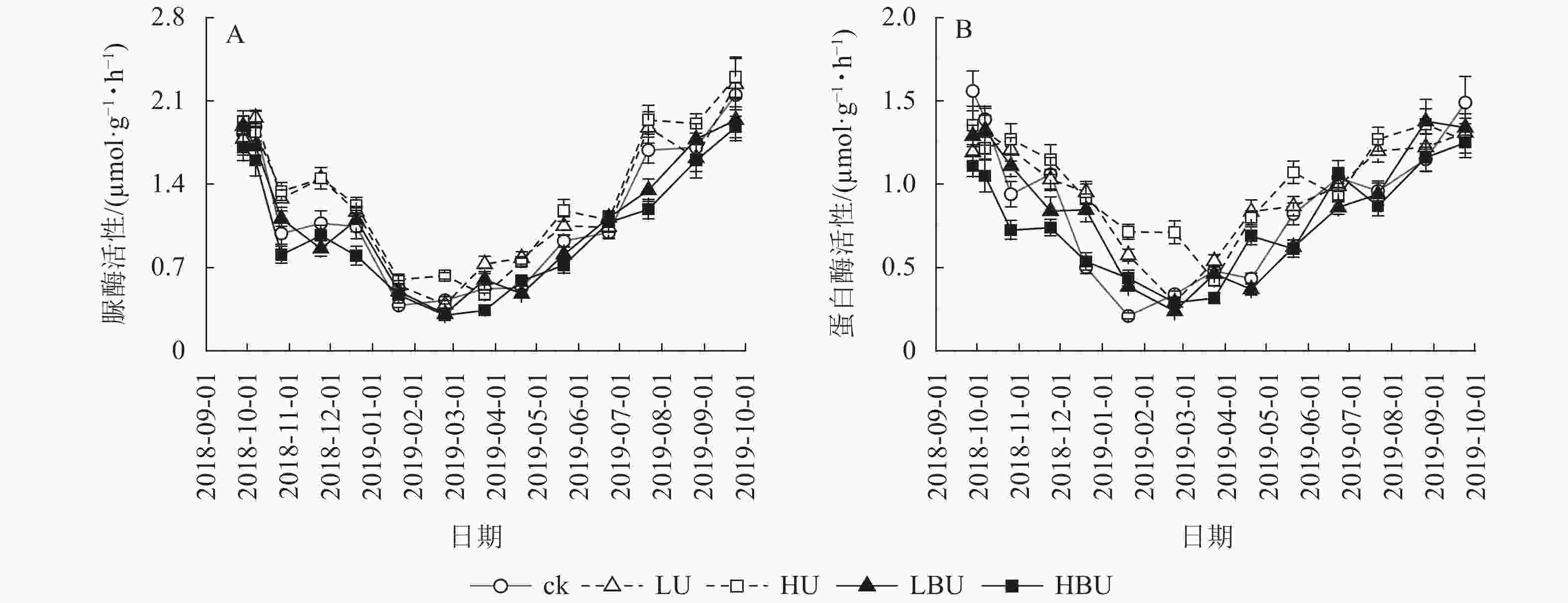

由图5可见:脲酶与蛋白酶活性随季节变化呈现夏季高、冬季低的规律特征。相比于ck,LU和HU处理导致脲酶活性年均值分别提高了11.1%和15.6%;LBU和HBU处理使毛竹林土壤脲酶活性年均值分别降低了3.5%和12.9%(表2)。相比于ck,LU和HU处理均导致蛋白酶活性年均值显著增加,增幅分别为10.2%和17.0%;LBU和HBU处理则降低了土壤蛋白酶活性年均值,降幅为2.3%和12.5% (表2)。

-

由表3可见:在所有处理下,土壤N2O通量与土壤温度、WSON、脲酶和蛋白酶活性均呈极显著相关(P<0.01);与NH4 +-N质量分数呈现显著相关性(P<0.05);但与土壤含水量均无显著相关性。在ck、HU、LBU和HBU处理下,毛竹林土壤N2O排放通量与土壤NO3 −-N和MBN质量分数均呈显著相关(P<0.05),在LU处理下毛竹林土壤N2O排放通量与土壤NO3 −-N和MBN质量分数无显著相关性。

土壤因子 各处理土壤N2O与土壤因子的相关性 ck LU HU LBU HBU R2 P R2 P R2 P R2 P R2 P 土壤温度 0.75 <0.01 0.68 <0.01 0.77 <0.01 0.78 <0.01 0.62 <0.01 土壤含水量 0.18 >0.05 0.13 >0.05 0.16 >0.05 0.24 >0.05 0.20 >0.05 土壤NH4 +-N 0.73 <0.01 0.32 <0.05 0.30 <0.05 0.51 <0.01 0.46 <0.01 土壤NO3 −-N 0.47 <0.01 0.23 >0.05 0.31 <0.05 0.51 <0.01 0.52 <0.01 土壤WSON 0.46 <0.01 0.71 <0.01 0.68 <0.01 0.59 <0.01 0.48 <0.01 土壤MBN 0.51 <0.01 0.23 >0.05 0.35 <0.05 0.66 <0.01 0.76 <0.01 土壤脲酶 0.77 <0.01 0.52 <0.01 0.69 <0.01 0.90 <0.01 0.89 <0.01 土壤蛋白酶 0.78 <0.01 0.50 <0.01 0.62 <0.01 0.82 <0.01 0.75 <0.01 Table 3. Relationships between soil N2O efflux and environmental factors in a Ph. edulis forest

-

本研究发现,不同水平尿素处理均显著提高了毛竹林土壤N2O年累积排放量;高水平炭基尿素处理显著减少了土壤N2O年累积排放量。CORRÊA等[33]研究发现:尿素施用显著增加了暖季牧场土壤N2O的排放,李正东等[34]对小麦Triticum aestivum田土壤添加不同类型的炭基肥,发现与常规施肥相比,炭基复合肥显著降低了土壤N2O的排放通量,减排幅度为56.0%~65.4%,这与本研究结果相似。施用炭基尿素减少土壤N2O排放的原因可能是炭基尿素中的生物质炭增加了土壤孔隙结构,改善了土壤通气性,吸附了大量活性氮组分,从而显著降低了土壤反硝化速率,在一定程度上降低了N2O的排放速率[35-36]。

-

本研究中,在ck、LU、HU、LBU和HBU处理下,土壤温度与毛竹林土壤N2O通量均呈现极显著相关性。该结果与DENG等[37]的研究结果相一致。DUAN等[38]研究温室菜地土壤发现:土壤N2O排放通量与土壤温度也具有十分密切的关系。因此,土壤温度是驱动土壤N2O排放变化的重要环境因子。但是,本研究结果发现不同处理之间的土壤温度没有显著差异,说明炭基尿素和尿素并不是通过改变土壤温度来影响土壤N2O排放。这一发现与BAYER等[39]的结果一致,其研究表明土壤N2O排放受不同管理措施影响,但这种影响不是通过改变土壤温度所致。

另外,本研究中,在ck、LU、HU、LBU和HBU处理下,土壤N2O通量与含水量之间的相关性均未达到显著水平。以往的研究结果也表明:人为管理的草甸草原土壤N2O排放与土壤含水量之间也无相关性[40];而ADELEKUN等[41]的研究结果表明:尿素处理下,土壤水分与N2O通量存在显著相关性。不同研究结果的差异可能是由土壤类型、植被类型、集约管理措施和气候条件的差异所致[42-43]。在本研究中,土壤N2O排放与含水量之间无相关性可能是因为在亚热带地区降雨量充足,大部分季节土壤含水量均较高[44-45],因此,土壤含水量可能不是驱动土壤N2O排放变化的关键因子。

-

本研究发现,相比于ck,炭基尿素和尿素处理下的土壤NH4 +-N和NO3 –-N质量分数均显著增加,其原因可能是炭基尿素和尿素中的氮素成分可以显著增加土壤有机氮库[46]。另外,本研究结果表明:在ck、HU、LBU和HBU处理中,土壤NH4 +-N和NO3 –-N质量分数与N2O通量存在显著相关;在LU处理中,土壤NH4 +-N质量分数与N2O通量也存在显著相关。但尿素处理增加了N2O通量,炭基尿素处理降低了N2O通量。上述结果表明:尿素处理通过增加NH4 +-N和NO3 –-N质量分数来增加土壤N2O排放[43];而炭基尿素处理并不是通过影响NH4 +-N和NO3 –-N质量分数来降低土壤N2O排放。

与ck相比,HU处理显著增加了土壤WSON质量分数,而炭基尿素处理显著降低了土壤WSON质量分数,并且土壤N2O通量与WSON质量分数极显著相关。WSON质量分数降低的可能原因可能是:①炭基尿素减少了土壤中有机氮化合物的降解[47];②炭基尿素中生物质炭成分具有很高的比表面积,可以吸附可溶性的有机氮,从而降低WSON质量分数[28]。这些结果表明:炭基尿素处理可能是通过减少土壤WSON质量分数从而降低土壤N2O通量。

-

本研究发现:炭基尿素处理显著降低了蛋白酶活性,HBU处理显著降低了土壤脲酶活性。这与ZHOU等[43]的结果相一致。炭基尿素处理下脲酶和蛋白酶活性降低的原因可能是:①炭基尿素处理中生物质炭成分具有较高的比表面积和阳离子交换量,可以吸附活性有机碳和有机氮,从而降低其对土壤微生物的生物有效性[48-50];②炭基尿素处理中生物质炭成分对有机物的吸附作用,降低了参与氮循环过程中的土壤酶活性[50-53]。另外,本研究发现:在炭基尿素处理中土壤N2O通量与脲酶和蛋白酶活性极显著相关。这表明炭基尿素处理抑制脲酶和蛋白酶活性可能是其减少土壤N2O通量的机制之一。

尿素处理显著增加了土壤蛋白酶和脲酶活性,这与LIU等[54]的结果相一致。LIU等[54]的研究表明:化肥处理显著提高了玉米Zea mays土壤脲酶活性。SAHA等[55]也发现:在旱作大豆Glycine max-小麦轮作体系中,施用化肥显著提高了土壤蛋白酶活性。尿素处理下土壤脲酶和蛋白酶活性升高的机制可能是由于尿素施入提高了土壤氮素的有效性,从而增加了氮循环过程中相关酶的底物,提高了酶的活性[5,10]。此外,尿素处理下,土壤N2O通量与脲酶和蛋白酶活性极显著相关。上述结果说明:尿素处理刺激脲酶和蛋白酶活性可能是其提高土壤N2O通量的机制之一。

-

尿素处理显著增加了毛竹林土壤N2O的年累积排放量,而炭基尿素处理显著降低了毛竹林土壤N2O的年累积排放量。这表明:相比于尿素,施用炭基尿素可以减缓毛竹林土壤N2O的排放。此外,本研究结果表明:炭基尿素减少土壤WSON质量分数以及抑制脲酶和蛋白酶活性可能是其降低土壤N2O排放的重要机制;尿素处理增加土壤N2O排放的重要机制是其提高了土壤WSON和NH4 +-N质量分数以及脲酶和蛋白酶活性。综上所述,在人工林经营管理实践中,采取施用炭基尿素来代替施用尿素的措施,在给植物提供充足氮素养分并改善土壤理化性质的同时,可以减少土壤温室气体的排放。

Effects of biochar-based urea and common urea on soil N2O flux in Phyllostachys edulis forest soil

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220254

- Received Date: 2022-03-28

- Accepted Date: 2022-08-06

- Rev Recd Date: 2022-08-06

- Available Online: 2023-01-18

- Publish Date: 2023-01-17

-

Key words:

- Phyllostachys edulis forest /

- N2O /

- biochar-based urea /

- N form /

- fertilization

Abstract:

| Citation: | CAO Shanzhi, ZHOU Jiashu, ZHANG Shaobo, et al. Effects of biochar-based urea and common urea on soil N2O flux in Phyllostachys edulis forest soil[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2023, 40(1): 135-144. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220254 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: