-

植物挥发性有机化合物(volatile organic compounds, VOCs)是一类经植物次生代谢合成并排放到空气中的小分子化合物,其年排放量占全球挥发性有机化合物年排放总量的90%以上[1]。VOCs的成分大约有3万多种[2],其中以异戊二烯和单萜为主[3],分别约占50%和15%[4]。已有研究表明:VOCs有助于提高人体免疫力,并对一些慢性疾病有预防作用[5−6],尤其是萜烯类物质对人体健康方面具有积极影响[7],如柠檬烯和蒎烯具有减轻炎症、缓解睡眠和心理压力的作用[8],芳樟醇具有抗抑郁和抗焦虑的效果[6, 9]。然而,随着城市化加速发展,大气、水、光、噪声等环境污染问题、城市热岛效应和现代快节奏生活造成的城市病严重威胁人类身心健康[10],慢性疾病患病率和致死率上升[11],因此,以森林环境作为康养手段来促进人体健康的需求逐渐增长[12],而森林分为不同的森林类型,通过对不同林分开展VOCs研究是森林康养开展的重要依据和前提,具有重要的现实意义[13]。

VOCs主要由植物叶片释放[2]。不同树种释放的VOCs种类具有高度特异性[14−15],并随森林光照度、温度和湿度等环境因子的日变化和季节变化产生差异[16],而且VOCs在大气中极易发生光化学反应,这就造成了森林环境中VOCs存在状态的不确定性。目前,关于VOCs的研究主要集中在叶片或单一树种[17−20],但基于不同林分类型VOCs释放特点及其与环境因子的关系研究较少[21],需要进一步研究探索。浙江省丽水白云国家森林公园拥有华东地区保存最完好的次生阔叶林,是开展森林旅游的重要场所。本研究以5种不同典型林分[杉木Cunninghamia lanceolata林、柳杉Cryptomeria fortunei林、阔叶混交林(青冈Cyclobalanopsis glauca和白栎Quercus fabri)、杉阔混交林(杉木和樟树Cinnamomum camphora)、毛竹Phyllosachys edulis林]为研究对象,比较分析不同典型林分类型VOCs的释放特点、释放日动态、空间分布特点及其与环境因子相关性,以期为森林康养活动的开展提供依据,同时为进一步构建森林挥发性有机化合物排放模型提供数据支持。

-

丽水白云国家森林公园位于丽水市城区北部(28°28′49′′~ 28°33′37′′N, 119°52′06′′~119°58′28′′E),森林面积为2 552.13 hm2,覆盖率达97.38%。地貌以低山丘陵为主,地势为西北向东南倾斜,地形复杂,海拔为51.2~1 073.2 m。该森林公园属中亚热带季风气候,四季分明,雨量充沛,年平均气温为18.1 ℃,年平均降水量为1 392.8 mm,降雨主要分布在4—10月,其中4—6月占全年降雨量46.2%。

研究选取杉木林(SM)、柳杉林(LS)、阔叶混交林(KY)、杉阔混交林(SK)、毛竹林(MZ)等5种典型林分为研究对象,每种林分设置20 m×20 m样地,并进行每木检尺,每个样地用5点采样法进行采样[22]。样地土壤均为黄壤。样地概况见表1。

林分类型 海拔/

m坡向/

(°)坡位 树高/

m林分密度/

(株·hm−2)杉木林(SM) 940 100 阳坡 11.83 23 000 柳杉林(LS) 900 300 阴坡 22.23 10 000 阔叶混交林(KY) 920 145 阳坡 9.50 15 000 杉阔混交林(SK) 920 266 阴坡 12.90 20 000 毛竹林(MZ) 660 200 阴坡 17.82 3 700 Table 1. Sample site overview

-

不同林分VOCs组分及摩尔分数采用吸附管富集离线测定:于2021年9月25—29日9:00—16:00进行采样。每块样地设置2个采样点,每种林分连续测定5 d,每个林分采集10个样品,5个林分共获得样品50个。采样设备使用便携式采样仪(Mini Pump,北京市劳动保护科学研究所),设置流速75 mL·min−1,每个样品采集空气31.5 L。吸附管为不锈钢管(通用型5266,MARKES),用于吸附VOCs。采样后使用便携式气相色谱-质谱联用仪(GC-MS,EXPEC 3500)吸附管模块进行二次热解吸并分析测试,获得各林分5 d VOCs平均摩尔分数。

-

不同林分VOCs日变化采用探头直接采样测定:于2021年9月25—29日分别在各林分环境中进行采样。仪器配备1.5 m采样探头和10.0 m特氟龙管,能够分别采集林冠层(8.0~12.0 m)和人体呼吸层(1.5 m)空气。测定时段为9:00—16:00,每次采样时长为20 min,采样间隔1 min,共获得110个样品。

-

使用质谱仪数据分析软件,结合保留时间、峰面积、标准质谱图和美国国家标准与技术研究所(NIST)的标准参考数据库判断组分种类,使用面积归一化外标法计算摩尔分数。多点外部标准曲线使用物质标准品(坛墨质检)配置各摩尔分数梯度标准溶液(5、20、50、80、100 nmol·mol−1)后,以便携式气相色谱-质谱联用仪进行定量。根据实测结果和文献研究[23−24],选取包括2-蒎烯、β-蒎烯在内的12种萜类物质作为林分树木释放的目标物质,分析其摩尔分数变化。萜烯类物质标样有:叶醇、萜烯醇、3-蒈烯、2-蒎烯、崁烯,其他物质使用臭氧前体混合物(PAMS)气体标样定量。标样之外的单萜摩尔分数使用2-蒎烯的标准曲线公式计算,含氧萜烯衍生物摩尔分数使用萜烯醇的公式计算,芳香类化合物使用甲苯的标准曲线代替,脂肪酸衍生物和其他物质使用叶醇的标准曲线代替。每个目标化合物的绝对摩尔分数根据标准曲线计算,目标化合物的峰面积和已知标准摩尔分数间的拟合度R2>0.99。

-

森林环境因子使用浙江农林大学自主研发的环境气象监测站测定。气象站距地面高度2.0 m,布设于样地中心。测量指标包括气温(T)、湿度(RH)、光照度(E)、臭氧(O3)、细颗粒物(PM2.5)、可吸入颗粒物(PM10)、风向、风速、二氧化碳(CO2)。数据采集频率为1 min,测量数据自动实时上传到网络平台。

-

对各林分VOCs摩尔分数日均值和各时段均值进行单因素方差分析(P<0.05);使用皮尔逊相关分析确定环境因子与单萜摩尔分数日变化的相关性,显著性水平为0.05,采用Excel 2016和R 4.1.2对数据进行统计并作图。

-

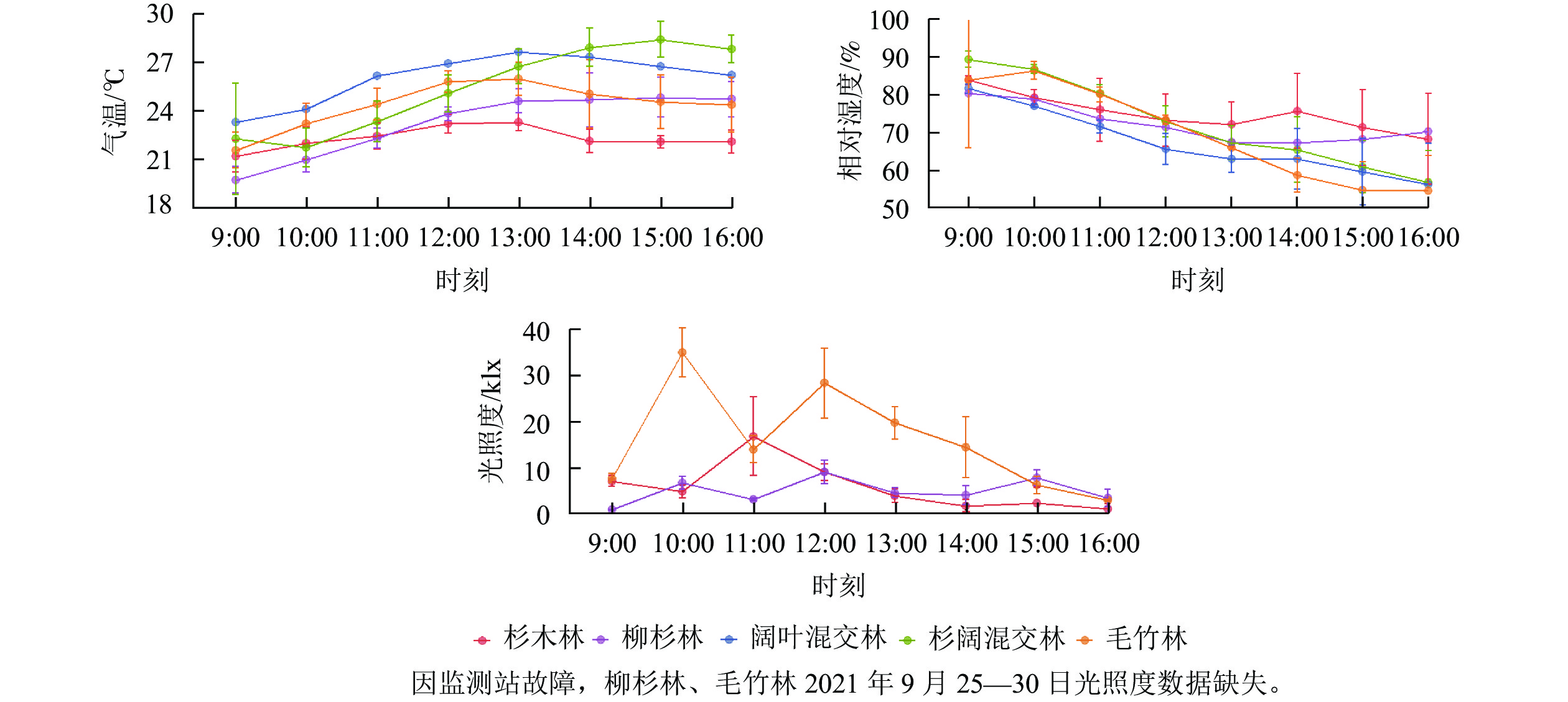

由图1可见:柳杉林气温最高,为26.0 ℃,杉木林最低,为22.0 ℃,且全天气温变化幅度不大,各林分全天气温呈逐渐上升趋势;相对湿度均呈下降趋势,杉木林平均相对湿度最高,为76.2%,阔叶混交林最低,为69.0%,各林分相对湿度波动范围相近,仅毛竹林在9:00和16:00相对湿度变化差异大;林内光照度不仅受天气的影响,还与坡向、郁闭度等相关,各林分光照度日变化各不相同。杉木林内平均光照度变化呈单峰型,在11:00出现最高值,为16.87 klx;阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林呈双峰型,在10:00和12:00别达到35.02、28.43 klx和9.10、6.78 klx。相较而言,阔叶混交林光照度波动范围最大,变化最为剧烈,杉阔混交林波动最为平缓,杉木林在光照度峰值时波动剧烈。

-

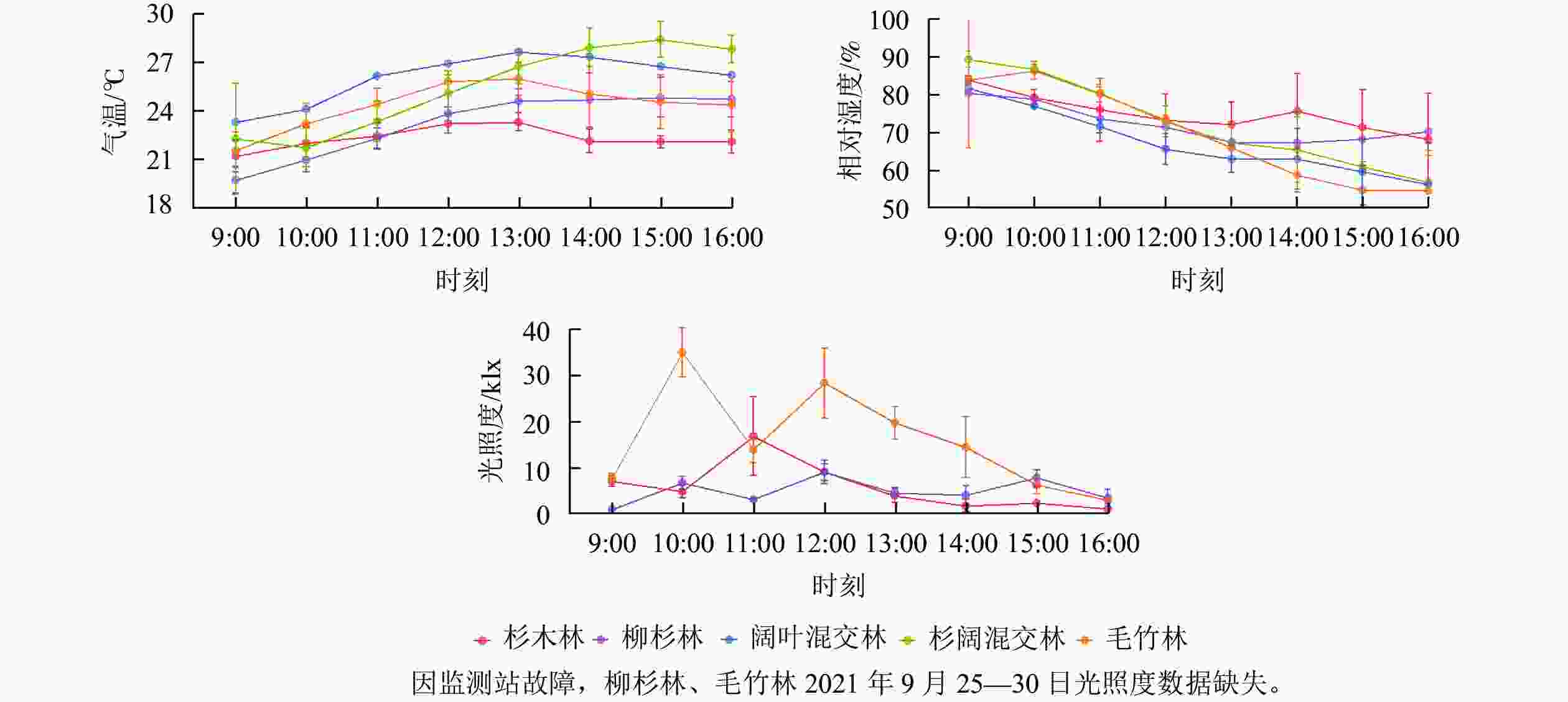

5种林分VOCs摩尔分数及组分如图2所示。杉木林、柳杉林、阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林的主要组分为单萜,而毛竹林的主要组分是异戊二烯,单萜次之。柳杉林的单萜物质占比最大,达58.9%,毛竹林最少,为16.9%。除单萜和异戊二烯外,各林分其他VOCs组分排序为:芳香类化合物占比最高,占20%左右;其次为醇类、醛类等其他物质,最少的是脂肪酸衍生物。

5种林分的VOCs摩尔分数从高到低依次为毛竹林(7.35 nmol·mol−1)、柳杉林(5.36 nmol·mol−1)、杉阔混交林(4.20 nmol·mol−1)、阔叶混交林(4.04 nmol·mol−1)、杉木林(3.57 nmol·mol−1)。5种林分单萜摩尔分数从高到低依次为柳杉林(3.15 nmol·mol−1)、阔叶混交林(1.89 nmol·mol−1)、杉木林(1.69 nmol·mol−1)、杉阔混交林(1.47 nmol·mol−1)、毛竹林(1.24 nmol·mol−1),柳杉林的单萜摩尔分数与其他林分存在显著差异(P<0.05)。

由表2可见:毛竹林释放的单萜种类最多,为9种,其次为阔叶混交林,释放了8种,杉木林和柳杉林释放了6种,杉阔混交林释放了5种。杉木林和柳杉林释放2-蒎烯和β-蒎烯最多,杉阔混交林释放左旋-β-蒎烯最多,5种林分都释放的单萜有2-蒎烯、左旋-β-蒎烯、β-蒎烯和薄荷脑,其中柳杉林和毛竹林释放的薄荷脑是其他林分的10倍以上。异戊二烯主要在毛竹林、阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林中释放,其中毛竹林释放最多,且释放量远高于其他林分。

林分类型 VOCs各组分摩尔分数/(nmol·mol−1) 异戊二烯(C5H8) 单萜 2-蒎烯(C10H16) 左旋-β-蒎烯(C10H16) 月桂烯(C10H16) β-蒎烯(C10H16) 莰烯(C10H16) 杉木林 0.004±0.000 1.100±0.420 0.130±0.040 0.900±0.000 0.140±0.040 − 柳杉林 0.070±0.000 0.100±0.440 0.170±0.080 0.130±0.020 0.190±0.050 − 杉阔混交林 0.400±0.120 0.750±0.180 1.570±1.030 − 0.100±0.040 − 阔叶混交林 0.740±0.330 0.760±0.470 0.130±0.010 0.080±0.060 0.166±0.050 0.120±0.003 毛竹林 4.800±1.560 0.770±0.200 0.090±0.010 0.090±0.050 0.200±0.040 0.370±0.000 林分类型 VOCs各组分摩尔分数/(nmol·mol−1) 单萜 芳樟醇(C10H18O) 薄荷脑(C10H20O) 柠檬烯(C10H16) 3-蒈烯(C10H16) 罗勒烯(C10H16) 萜烯醇(C10H18O) 杉木林 0.002±0.000 0.003±0.000 − − − − 柳杉林 − 0.030±0.000 0.050±0.004 − − − 杉阔混交林 − 0.003±0.001 − 0.010±0.004 − − 阔叶混交林 − 0.003±0.000 0.070±0.000 − 0.100±0.000 − 毛竹林 − 0.010±0.005 0.200±0.000 0.001±0.000 − 0.004±0.001 说明:−表示未检出。 Table 2. Average daily isoprene and monoterpene content of 5 forest stands

-

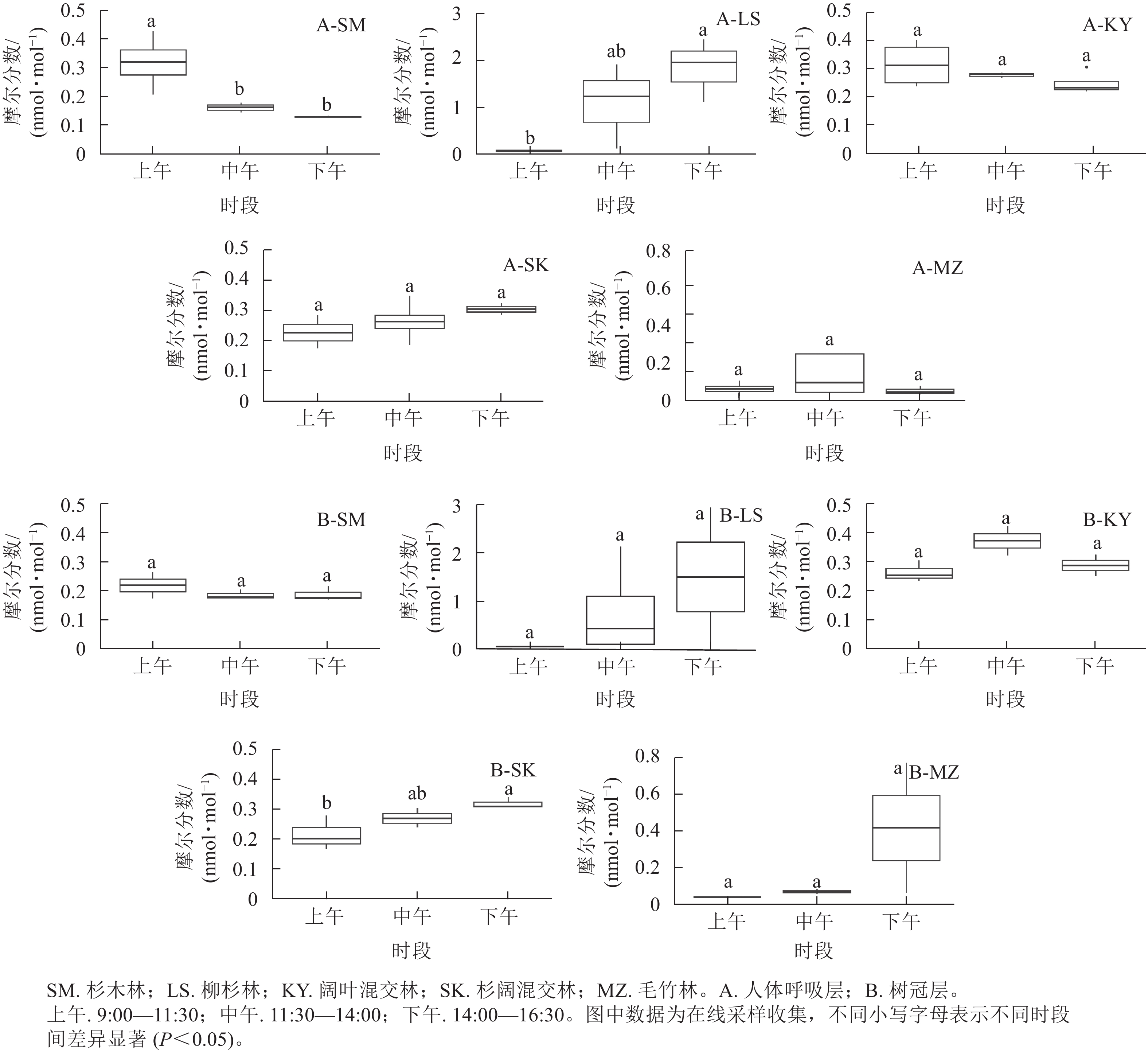

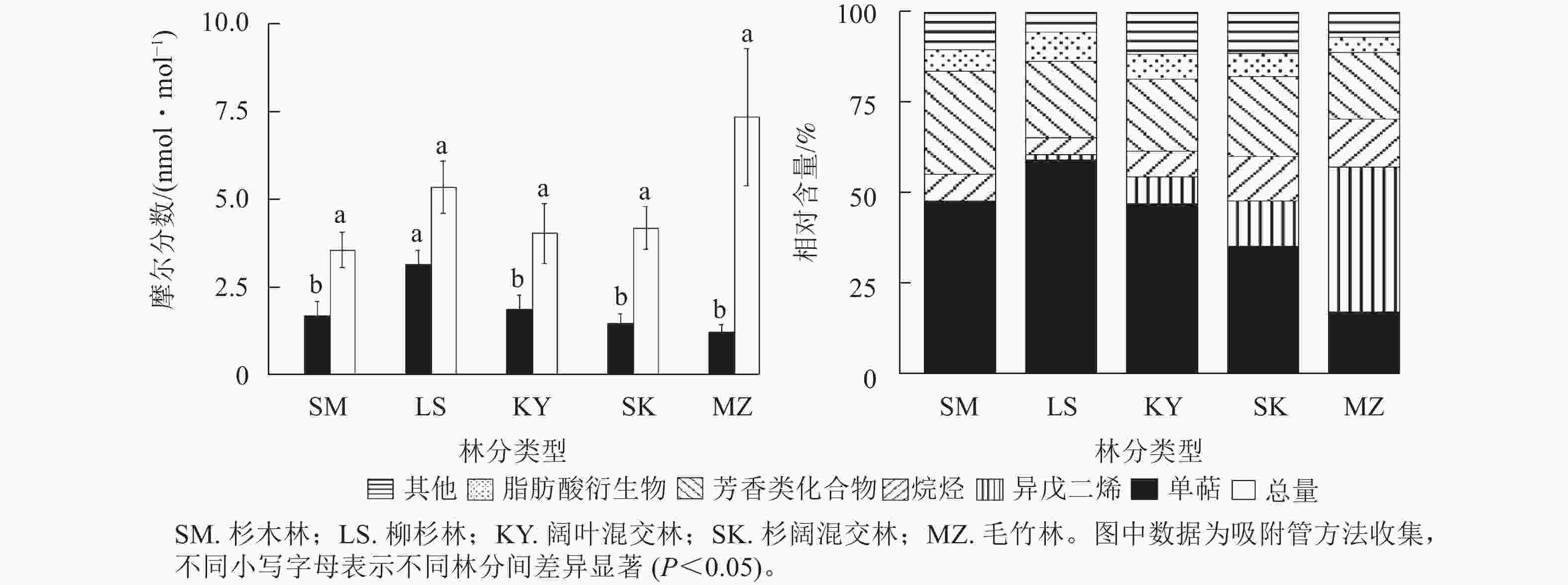

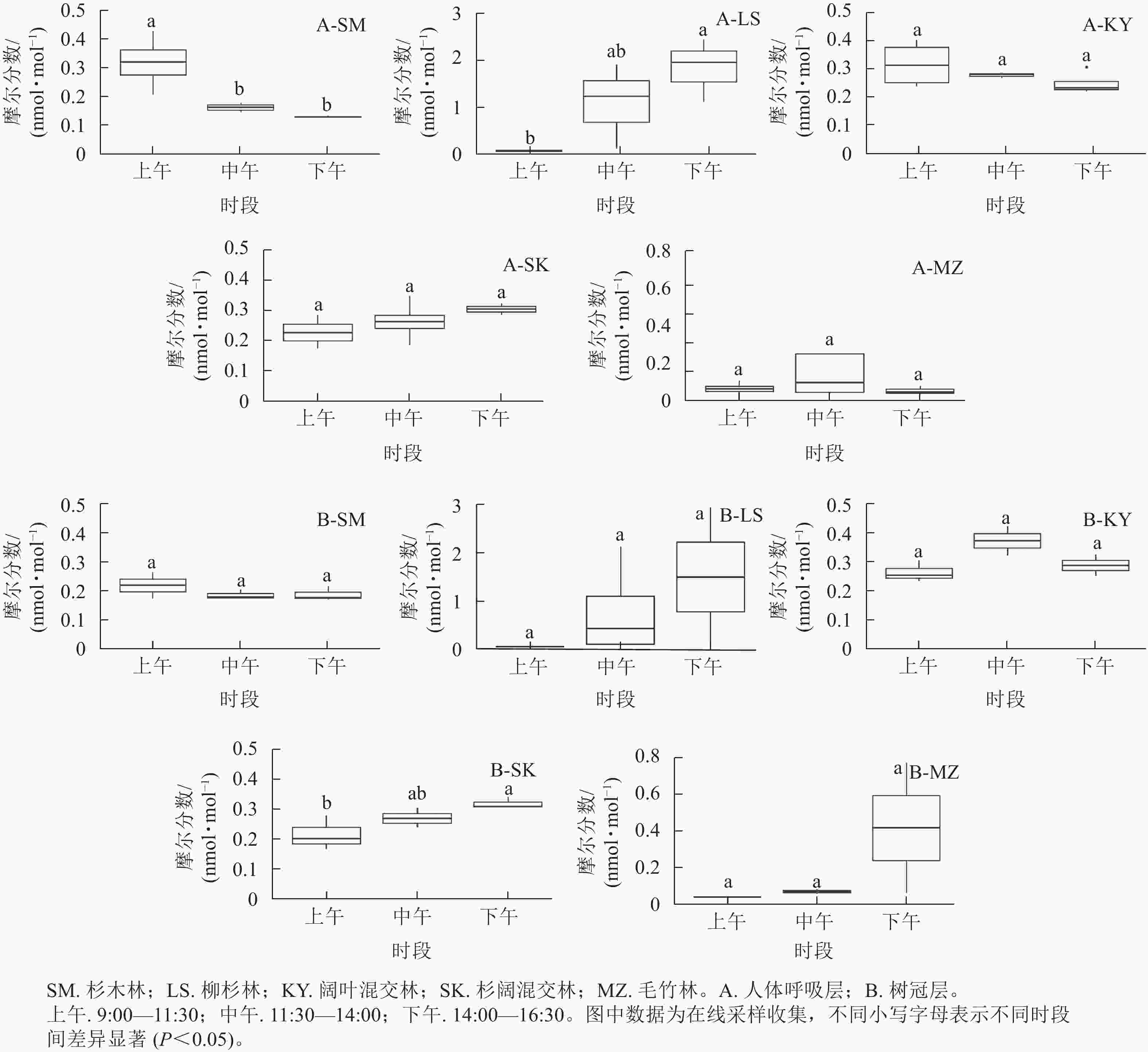

5种不同典型林分单萜摩尔分数日变化见图3。由图3可知:各林分单萜摩尔分数在不同高度上的日变化动态不同,但同一林分树冠层和人体呼吸层日变化趋势基本一致。在树冠层,柳杉林、杉阔混交林和毛竹林的单萜摩尔分数全天呈上升趋势,杉木林呈下降趋势,阔叶混交林呈先上升后下降趋势。柳杉林下午的单萜摩尔分数最高,为3.12 nmol·mol−1,其次是毛竹林下午的单萜摩尔分数,为0.77 nmol·mol−1,而杉木林、阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林全天单萜摩尔分数波动区间相近,为0.20~0.40 nmol·mol−1。在人体呼吸层,柳杉林和杉阔混交林呈全天上升趋势,杉木林和阔叶混交林呈下降趋势,毛竹林呈先上升后下降趋势。下午时段的柳杉林单萜摩尔分数达各林分全天峰值,为2.44 nmol·mol−1,其次为中午时段的毛竹林,达0.56 nmol·mol−1,阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林的单萜摩尔分数波动范围也为0.20~0.40 nmol·mol−1,杉木林则为0.10~0.40 nmol·mol−1。总体而言,在树冠层和人体呼吸层单萜摩尔分数最高的林分是柳杉林,其他林分的单萜摩尔分数量级较为相近,均未超过1.00 nmol·mol−1。在树冠层,杉阔混交林下午的单萜摩尔分数显著高于上午(P<0.05),在人体呼吸层,杉木林单萜摩尔分数在上午显著高于中午和下午(P<0.05),柳杉林则是在下午显著高于上午(P<0.05)。

-

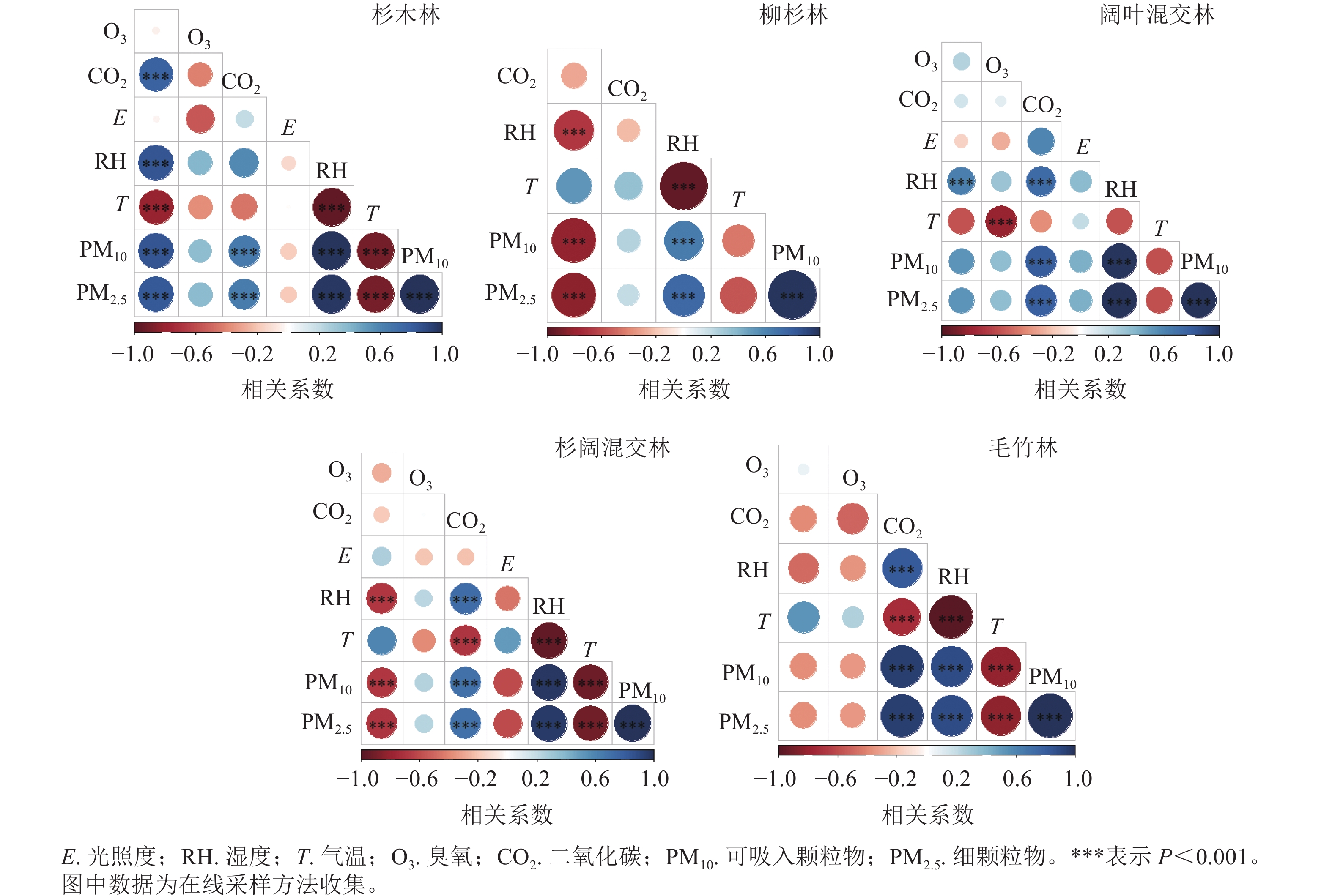

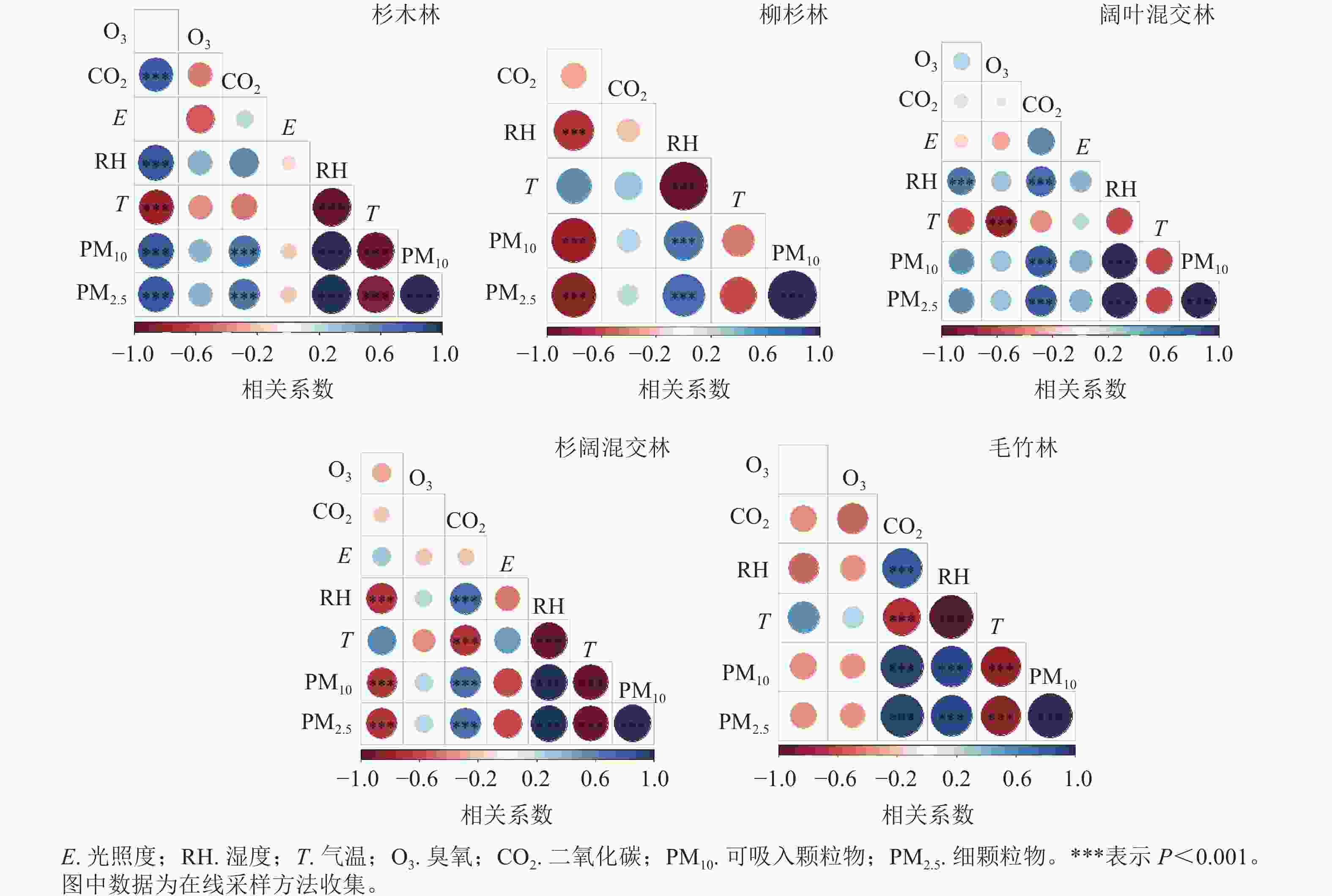

空气中单萜受环境影响容易通过光化学反应转化成为臭氧、二次有机气溶胶等二次污染物[25]。5种林分人体呼吸层单萜摩尔分数与环境因子相关性见图4。由图4可知:整体而言,杉木林单萜摩尔分数与湿度、CO2、PM2.5和PM10等呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),相关系数分别为0.77、0.84、0.84、0.82,与气温呈极显著负相关(P<0.01),相关系数为−0.81,与臭氧、光照度无显著相关性。柳杉林单萜摩尔分数与湿度、PM2.5和PM10呈极显著负相关(P<0.001),相关系数分别为−0.68、−0.81和−0.83,与CO2和气温无显著相关。阔叶混交林单萜摩尔分数与湿度呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),相关系数为0.63,与其他环境因子无显著相关;杉阔混交林单萜摩尔分数与湿度、PM2.5和PM10都呈极显著负相关(P<0.001),相关系数分别为−0.68、−0.68和−0.69,与臭氧、CO2、光照和气温无显著相关性;毛竹林单萜摩尔分数与各环境因子没有显著相关性。

Figure 4. Stratified correlation between monoterpene content and environmental factors of 5 forest stands

各环境因子的相关性比较中,5种林分的PM2.5和PM10均与湿度呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),同时PM2.5和PM10之间也呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),杉木林、杉阔混交林和毛竹林的PM2.5和PM10都与气温呈极显著负相关(P<0.001)。杉阔混交林、阔叶混交林和毛竹林的CO2与湿度、PM2.5和PM10都呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),杉木林的CO2只与PM2.5和PM10呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),柳杉林的CO2与其他环境因子无显著相关。

-

本研究中杉木林、柳杉林、杉阔混交林和阔叶混交林释放VOCs均以单萜为主,毛竹林以异戊二烯为主。杉木林、柳杉林和杉阔混交林的VOCs释放结果与VALERIE等[26]和LUN等[27]的结果一致。LUN等[27]发现:油松Pinus tabulaeformis、侧柏Platycladus orientalis等常绿针叶树种主要释放的组分为2-蒎烯、柠檬烯等。同时阔叶树种中的栓皮栎Quercus variabilis主要释放异戊二烯。尽管栎属Quercus树种被认为是释放异戊二烯较多的树种,但也能释放单萜[28]。本研究中,得出阔叶混交林VOCs组分仍以单萜为主的结论,印证了前人研究结果[29],也表明阔叶树种VOCs种类的释放相对复杂。毛竹林VOCs释放则以异戊二烯为主,与OKUMURA等[30]的研究结果一致。前人研究表明:除异戊二烯外最常见的VOCs是单萜[31−32],芳香族化合物也是VOCs的重要组成部分[14],这也与本研究各林分VOCs组分结果相符。

已有研究报道以针叶树为主的林分空气中单萜浓度更高[33],但本研究发现杉木林单萜摩尔分数低于阔叶混交林,可能是因为阔叶混交林的温度和光照度高于杉木林,促进了其冠层单萜的合成与释放[34−36]。另外,本研究还发现柳杉林的单萜摩尔分数最高,可能与以下几个因素有关:一是柳杉的单萜释放能力强,是高释放植物[35],因此单位时间内叶片的单萜释放量大;二是柳杉林冠层高度更大,郁闭度高,空气对流相对较低,造成单萜在林内的沉降与富集;三是柳杉林气温高于其他林分,气温越高,释放量越大[37]。

-

森林环境中,温湿度等环境因子存在日变化,且因森林结构不同其变化情况各异。林分释放单萜水平受到温度在内的多种环境因素影响[6, 36],因此单萜摩尔分数日变化形式也存在林分上的差异。除阔叶混交林和毛竹林外,其余各林分不同层单萜摩尔分数的数量级、日变化趋势和变化幅度基本一致。这与前人研究中单萜在森林地面附近浓度最高的结果不同[38]。这可能是因为本研究中林分的平均高度较低,单萜沉降速度快,空气流通频繁造成的。光照度、湿度和温度影响冠层叶片单萜的释放[39]。本研究中杉木林与阔叶混交林、柳杉林与杉阔混交林分别呈现全天下降趋势和上升趋势,可能是因为前者位于阳坡,后者位于阴坡,其受光面和日照时间不同,导致林分单萜释放趋势不同。杉木林的单萜摩尔分数与气温显著相关,与陈静等[40]的研究结果相同,湿度在杉木林、杉阔混交林和阔叶混交林中都与单萜摩尔分数显著相关,这与KIM等[20]得出的结论相同。

叶片释放到空气中的萜烯类物质易发生光化学反应生成不同化合物[25, 41],进而影响大气中臭氧和二次有机气溶胶(secondary organic aerosols, SOA)的含量,两者对空气质量、大气辐射水平等至关重要,同时单萜是二次有机气溶胶的前体物[25]。研究表明:萜烯类物质发生光化学反应时产生的二次有机气溶胶具有良好的吸湿性和水溶性[42−44],且是PM2.5的重要组成部分[42],其形成不仅受到单萜浓度影响,还与空气湿度和大气成分有关。本研究发现:各林分PM2.5和PM10与湿度极显著正相关,与气温极显著负相关,同时PM2.5和PM10之间极显著正相关,与刘旭辉等[45]对林带内PM2.5和PM10与温湿度的关系研究结果一致。另外,对于单萜摩尔分数与环境因子的相关性,本研究结果表明:单萜摩尔分数与光照、气温、CO2、O3等因子的相关性不强,与部分前人研究结果相同[34, 46]。原因可能是本研究的环境监测站主要监测的是林下小气候环境,而前人研究中多为林冠上方大气环境,两者环境条件存在差异。如:林下的光照度可能受到林分冠层的遮蔽,温度和湿度受植物呼吸作用调控,单萜在林内的停留时间受林分郁闭度和空气湍流等的影响,因此,具体原因还需进一步深入研究。

-

通过对丽水白云国家森林公园5种不同典型林分的VOCs释放情况进行研究,结果表明:杉木林、柳杉林、阔叶混交林和杉阔混交林主要释放单萜,都可以作为森林康养选择的林分类型,其中,柳杉林的单萜摩尔分数和占比最高,因此,优先推荐选择柳杉林开展森林康养活动;康养时间的选择可参考人体呼吸层的单萜日变化规律,如杉木林的单萜摩尔分数上午显著高于中午和下午,如果选择此林分作为康养场所,上午时段最佳;柳杉林下午显著高于中午和上午,下午时段更好。

VOCs release characteristics of 5 typical stands in Baiyun National Forest Park and their relationship with environmental factors

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220676

- Received Date: 2022-10-31

- Accepted Date: 2023-03-29

- Rev Recd Date: 2023-03-11

- Available Online: 2023-09-26

- Publish Date: 2023-09-26

-

Key words:

- volatile organic compounds (VOCs) /

- monoterpenes /

- forest therapy /

- environmental factors /

- release characteristics

Abstract:

| Citation: | WU Qinjiao, SONG Yandong, TAO Shijie, et al. VOCs release characteristics of 5 typical stands in Baiyun National Forest Park and their relationship with environmental factors[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2023, 40(5): 930-939. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220676 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: