-

滇杨Populus yunnanensis为杨柳科Salicaceae杨属Populus青杨派树种,主要分布于云南中北部和南部、贵州西部及四川西南部等地区[1]。因速生性强、易无性繁殖和适应性强等优良特性[2],滇杨在中国西南地区具有重要的经济、生态和社会效益[3]。但传统的滇杨遗传育种面临易感染黑斑病以及易遭蛀干虫害等问题[1]。相比之下,转基因育种能够将所需基因引入植物基因组培育新品种以及创制新种质[4]。然而,有效遗传转化体系的缺乏严重制约了滇杨转基因育种和功能基因组研究。

目前,有关滇杨再生体系的建立鲜有报道,仅有张春霞等[5]、辛培尧等[6]以滇杨叶片、叶柄和茎段为外植体进行不定芽的诱导,但均难以形成愈伤组织,不利于滇杨的高效再生和遗传转化研究。而关于滇杨遗传转化的研究尚未开展。据此,本研究以滇杨叶片为外植体,探讨植物生长调节剂对叶片愈伤组织、不定芽及生根的影响,从而建立高效的滇杨再生体系。在此基础上,利用农杆菌Agrobacterium tumefaciens介导法对滇杨进行遗传转化研究,进而解析影响滇杨转化效率的各种因素,以期为滇杨的快速繁殖、定向育种及种质资源保存提供科学依据。

-

以西南林业大学苗木基地栽培的10年生滇杨优株为母株,采集1年生枝条,剪切为45 cm长度的枝段,于室温条件下水培,取嫩叶作为试验材料。

-

根癌农杆菌为GV3101,含β-D-葡萄糖苷酸酶(GUS)报告基因及卡那霉素(Kan)筛选标记的质粒载体pBI121 (pBI121-GUS),菌株和质粒均由实验室保存。

-

以嫩叶作为外植体,将叶片冲洗干净后置于体积分数为2%的次氯酸钠(NaClO)消毒150 s,用体积分数为75%的乙醇浸泡10 s,无菌水清洗3次,用无菌滤纸吸干叶片表面水分。将叶片剪切成1.0 cm2小方块(叶盘),叶背向下接种于分化培养基上。

-

将叶盘接种于含有噻苯隆(TDZ,质量浓度分别为0.001、0.002、0.005 mg·L−1)、萘乙酸(NAA,质量浓度分别为0.010和0.050 mg·L−1)的MS和1/2 MS培养基上进行诱导分化。每瓶接种4个外植体,每个处理接种10瓶,置于暗条件下培养,30 d后统计愈伤组织诱导率。

将获得的愈伤组织继续接种于上述培养基中进行不定芽诱导,置于光条件下培养, 30 d后统计不定芽诱导率。

-

以1/2 MS为基本培养基,添加不同质量浓度组合的NAA (0、0.010、0.050、0.100 mg·L−1)和吲哚乙酸(IBA,0、0.010、0.050、0.100 mg·L−1)。待不定芽生长至2~3 cm时转接于生根培养基中,每瓶接种3个不定芽,每个处理接种10瓶,置于光条件下培养,30 d后统计生根率和单株生根数。

以上培养基均添加20.0 g·L−1蔗糖和4.5 g·L−1琼脂,在光照强度为2 000~2 500 lx、光照时间为12 h(光)/12 h(暗)、温度为(25±2) ℃条件下培养。

-

采用液氮速冻法将pBI121-GUS质粒转化至农杆菌中,加入LB培养液,置于28 ℃恒温振荡培养箱(200 r·min−1)培养,待菌液吸光度D(600)达0.6~0.8时,吸取菌液,涂布于添加不同质量浓度头孢霉素(0、100、200、300和400 mg·L−1)的LB固体培养基上,28 ℃倒置培养48 h,观察农杆菌生长情况。同时,将叶盘接种于添加不同质量浓度头孢霉素(0、100、200、300和400 mg·L−1)的分化培养基上进行筛选,每瓶接种3个叶盘,每个处理接种10瓶。30 d后统计分化率。

-

将叶盘接种于添加不同质量浓度卡那霉素(0、10、20、30和40 mg·L−1)的分化培养基中进行筛选。每瓶接种3个叶盘,每个处理接种10瓶,置于暗条件下培养,30 d后观察统计不定芽生长情况。

-

取1.2.3获得的滇杨组培苗,将叶片剪切为1.0 cm2叶盘,采用吸光度D(600)为0.2、0.6和1.0的农杆菌菌液对其侵染,每种浓度侵染时间分别为5、10和15 min,侵染后分别进行共培养0、2和4 d。将共培养后的叶盘接种于含有头孢霉素和卡那霉素筛选培养基进行筛选。40 d后统计产生抗性芽的叶盘数,并统计转化率,转化率=产生抗性芽的叶盘数/叶盘总数×100%。当抗性芽高度达2~3 cm时,接种至生根培养基中培养约20 d。

-

取1.2.6中的抗性植株及野生型再生苗的叶片置入GUS染色液(体积比为X-Gluc Solution∶GUS Buffer=1∶50)中,抽真空30 min,37 ℃保育24 h,体积分数为75%的乙醇脱色3 h,观察叶片着色情况。进一步将GUS染色为蓝色的植株提取基因组DNA,以野生型再生苗为阴性对照,PCR扩增GUS基因,引物序列为GUS-F:5′-TCTCAGAAGACCAAAGGGCAA-3′;GUS-R:5′-TGCGCCAGGAGAGTTGTTG-3′,片段大小为2 239 bp。PCR扩增体系:12.5 µL Taq PCR Master Mix,1.0 µL DNA模板,GUS-F和GUS-R (10.0 µmol·L−1)各1.0 µL,ddH2O补足至20.0 µL。扩增条件:94 ℃预变性5 min;94 ℃变性30 s,55 ℃退火30 s,72 ℃延伸1 min,30个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。

-

所有数据采用Excel 2016进行记录处理,利用SPSS 26.0进行单因素方差分析(ANOVA),采用Duncan’s法进行差异显著性分析。

-

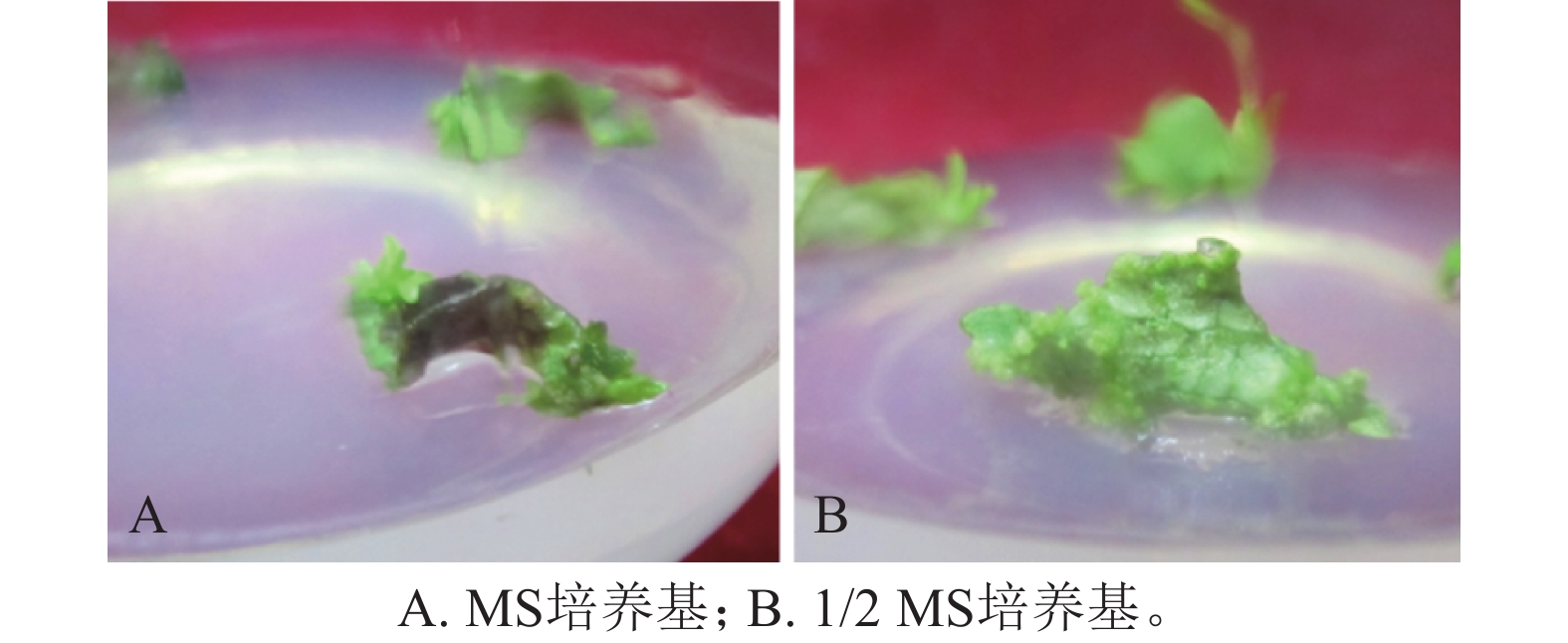

将滇杨叶盘接种于含TDZ和NAA的MS和1/2 MS培养基上,20 d后叶盘切口处形成淡绿色瘤状组织且出现芽点。接种于MS培养基的叶盘在30 d后仅于切口处长出少量愈伤组织(图1A),而接种于1/2 MS培养基的叶盘均分化出紧密的淡绿色愈伤组织(图1B)。因此,选取1/2 MS作为基本培养基进行愈伤组织和不定芽的诱导。

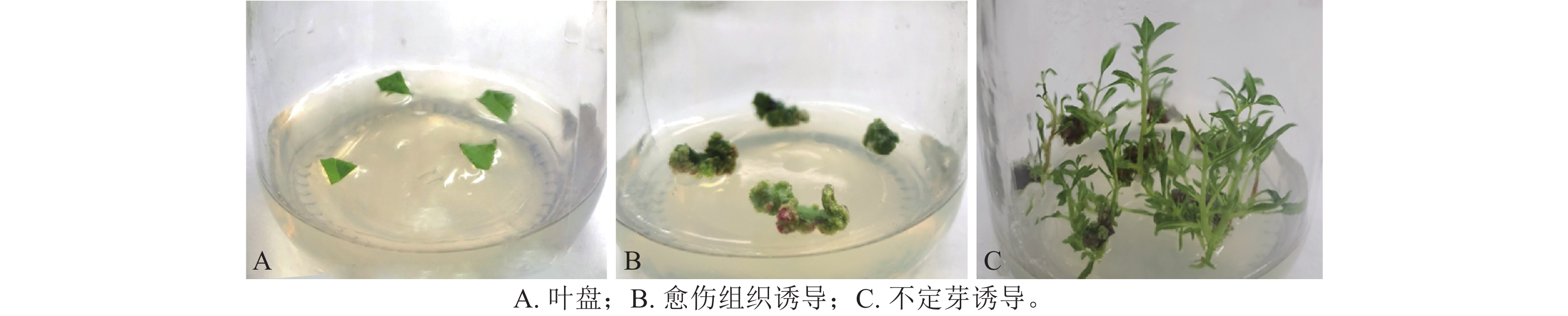

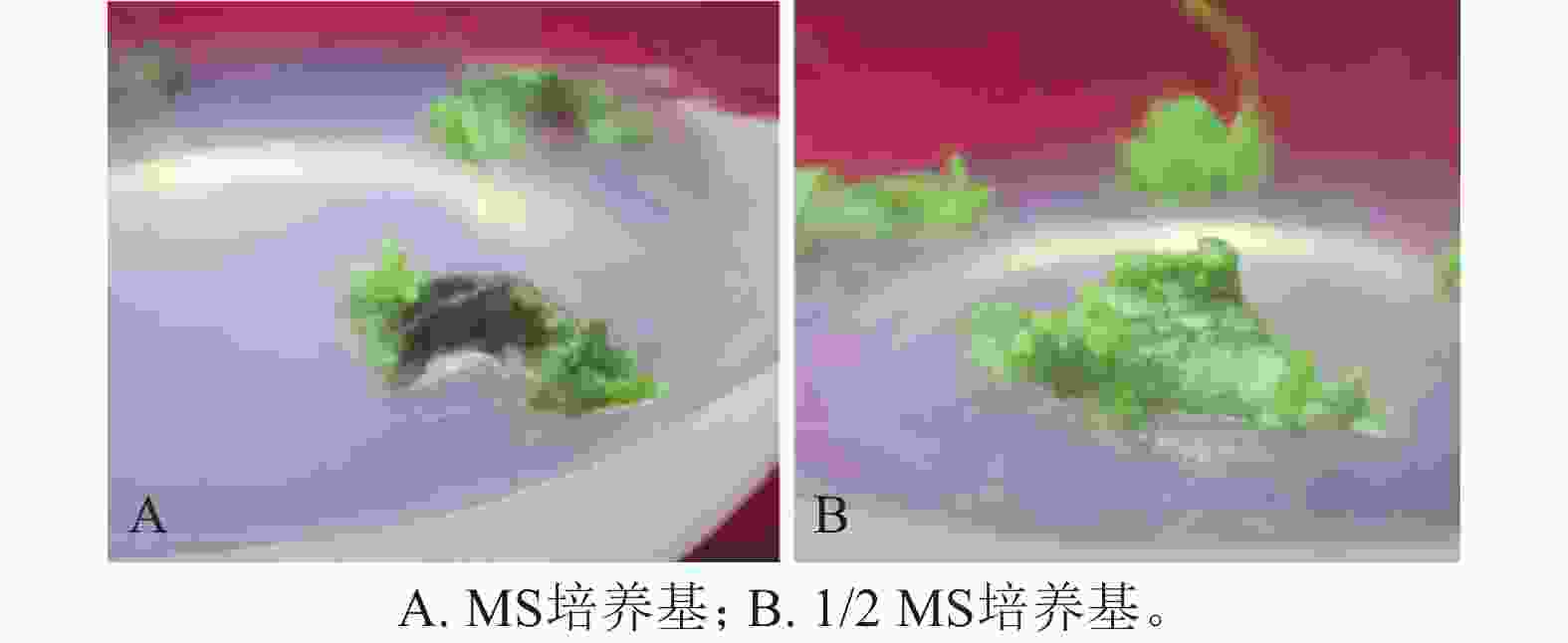

此外,将叶盘(图2A)置于含有TDZ和NAA不同质量浓度组合的1/2MS培养基上,30 d后统计愈伤组织诱导率及生长情况。结果表明(表1):组合0.005 mg·L−1TDZ和0.010 mg·L−1 NAA培养基中的诱导效果最好,愈伤组织紧实,呈浅绿色(图2B),且诱导率达91.70%。

植物生长调节剂组合 愈伤组织

诱导率/%愈伤组织状况 TDZ/

(mg·L−1)NAA/

(mg·L−1)0.001 0.010 36.00±12.73 e 浅黄色,疏松,长势较差 0.001 0.050 55.60±12.72 d 浅黄色,疏松,长势较差 0.002 0.010 63.90±9.64 cd 浅绿色,疏松,长势一般 0.002 0.050 83.30±8.35 abc 浅绿色,紧实,长势一般 0.005 0.010 91.70±8.35 ab 浅绿色,紧实,长势较好 0.005 0.050 77.80±4.79 bc 浅绿色,紧实,长势一般 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。同列不同小写字母表示不同组合间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 1. Effects of TDZ and NAA on callus induction

将上述愈伤组织转接入含有TDZ和NAA不同质量浓度组合的分化培养基中,30 d后统计不定芽诱导率及芽生长状况。由表2可知:在分化培养基中,组合0.002 mg·L−1TDZ 和0.010 mg·L−1NAA培养基诱导不定芽的效果最佳,诱导率达75.00%,与其余组合的差异均达到显著水平(P<0.05),且不定芽健壮、生长旺盛(图2C)。

植物生长调节剂组合 不定芽

诱导率/%不定芽生长状况 TDZ/

(mg·L−1)NAA/

(mg·L−1)0.001 0.010 8.30±14.43 cd 苗矮小,生长较差 0.001 0.050 5.50±4.79 cd 苗矮小,生长较差 0.002 0.010 75.00±14.43 a 苗健壮,生长旺盛 0.002 0.050 19.50±4.79 bc 苗细弱,生长一般 0.005 0.010 27.80±12.73 b 苗细弱,生长一般 0.005 0.050 16.60±14.43 bcd 苗细弱,生长一般 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。同列不同小写字母表示不同组合间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 2. Effects of TDZ and NAA on adventitious bud induction

-

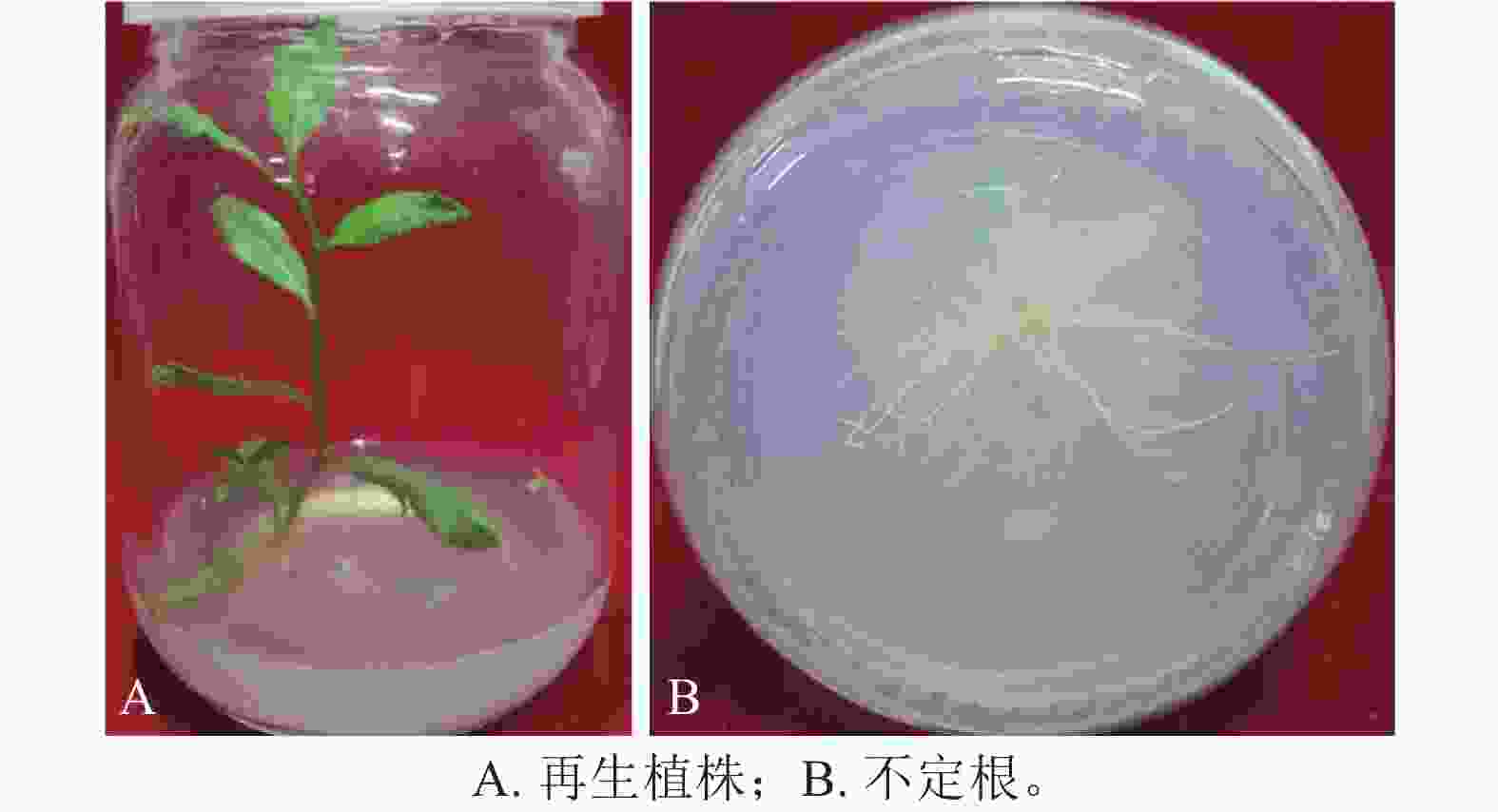

从表3可见:在组合为0.010 mg·L−1NAA和0.100 mg·L−1IBA的培养基中,植株生长旺盛(图3A),生根率高达96.70%,平均生根数为2.57条,均有较多的侧根及根毛(图3B);其次为组合0.010 mg·L−1NAA和0.050 mg·L−1IBA培养基,苗木长势较好,生根率为83.30%,平均生根数为1.93条。此外,当NAA为0.010 mg·L−1时,随着IBA质量浓度的增加,生根率逐渐升高,平均生根数也逐渐增多,同时不定根和组培苗的长势逐渐增强。而IBA为0.010 mg·L−1时,随着NAA质量浓度的增加,生根率逐渐降低,平均生根数逐渐减少,不定根和组培苗的长势减弱。因此,组合1/2 MS、0.010 mg·L−1NAA、0.100 mg·L−1 IBA培养基适合不定芽的生根诱导。

植物生长调节剂组合 生根率/% 平均生根数/条 生长状态 NAA/(mg·L−1) IBA/(mg·L−1) 0.000 0.000 63.30±5.77 bc 1.33±0.49 bc 主根细长、无侧根苗长势较好 0.010 0.000 56.70±15.28 c 0.97±0.51 c 主根短少、侧根少、苗长势一般 0.010 0.100 96.70±5.77 a 2.57±0.25 a 主根粗壮、侧根发达、苗健壮 0.010 0.050 83.30±5.77 ab 1.93±0.57 ab 主根较粗、侧根较多、苗长势较好 0.010 0.010 66.70±15.28 bc 1.10±0.44 c 主根粗壮、侧根较少、苗长势一般 0.000 0.010 70.00±10.00 bc 1.23±0.30 bc 主根短少、侧根少、苗长势一般 0.050 0.010 63.30±5.77 bc 0.77±0.15 c 茎部有短根、苗长势一般 0.100 0.010 60.00±26.46 bc 0.70±0.40 c 主根短少、侧根少、苗长势一般 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。同列不同小写字母表示不同组合间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 3. Effects of NAA and IBA on the rooting of adventitious bud

-

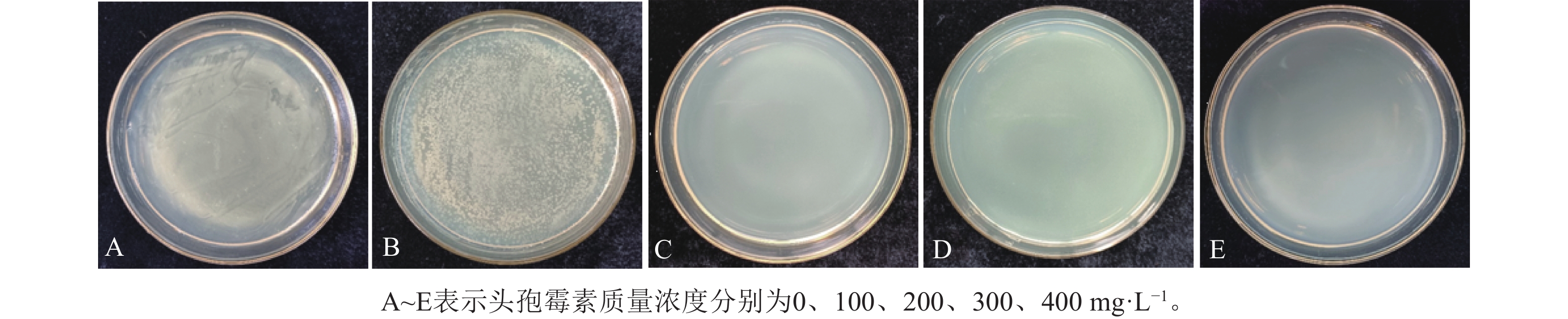

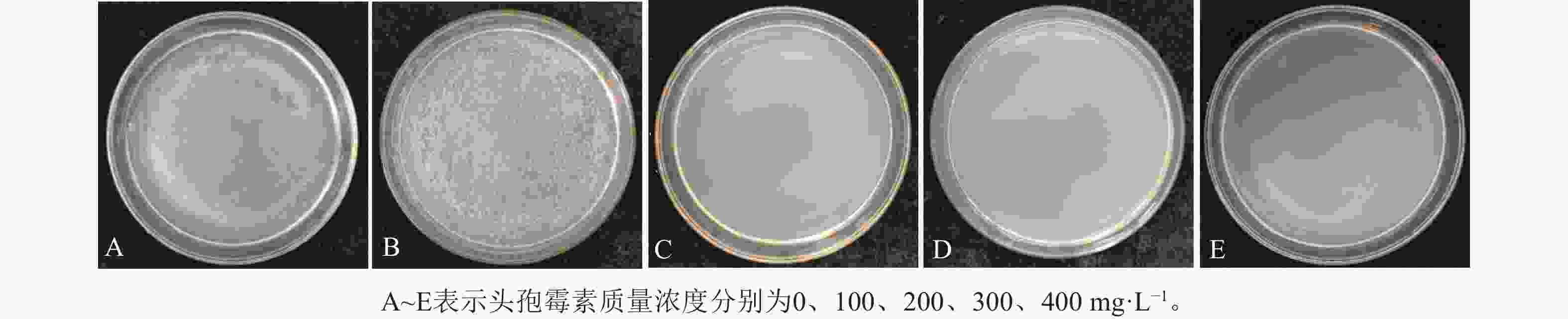

图4可见:当头孢霉素质量浓度为0时,农杆菌生长迅速,但随着头孢霉素质量浓度的增加,农杆菌的数量逐渐减少,当头孢霉素质量浓度≥200 mg·L−1时,可较好地抑制农杆菌的生长,此时,农杆菌数量为0 (图4)。此外,将叶盘接种至含有不同质量浓度头孢霉素(0、100、200、300和400 mg·L−1)培养基中进行培养,结果表明头孢霉素质量浓度为0时,叶盘分化率为97.20%,随着头孢霉素质量浓度的增加,叶盘的分化率无显著差异(表4)。因此,选取200 mg·L−1头孢霉素作为后续抑制农杆菌生长的最佳质量浓度。

头孢霉素质量

浓度/(mg·L−1)诱导率/% 生长状况 0 97.20±4.79 a 不定芽多,生长正常 100 88.90±12.73 a 不定芽较多,生长正常 200 83.30±8.35 a 不定芽较多,生长正常 300 83.30±8.35 a 不定芽较多,生长正常 400 83.30±8.35 a 不定芽较多,生长正常 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。同列不同小写字母表示不同组合间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 4. Effect of cefotaxime on regeneration of the adventitious buds of P. yunnanensis

-

由表5可知:当卡那霉素质量浓度为0时,叶盘分化率为88.90%。随着卡那霉素质量浓度的增加,叶盘分化率急剧下降。当卡那霉素质量浓度≥20 mg·L−1时,叶盘生长速度缓慢,叶盘开始变黄甚至褐化,且分化率均为0。因此,选取20 mg·L−1卡那霉素对滇杨转化植株进行抗性筛选。

卡那霉素质量

浓度/(mg·L−1)诱导率/% 生长状况 0 88.90±12.73 a 产生大量不定芽 10 38.90±12.73 b 产生少量不定芽 20 0.00±0.00 c 生长速度缓慢,无不定芽的形成 30 0.00±0.00 c 叶盘变黄 40 0.00±0.00 c 叶盘变黑死亡 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。同列不同小写字母表示不同组合间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 5. Effects of different concentrations of kanamycin on leaf disc differentiation

-

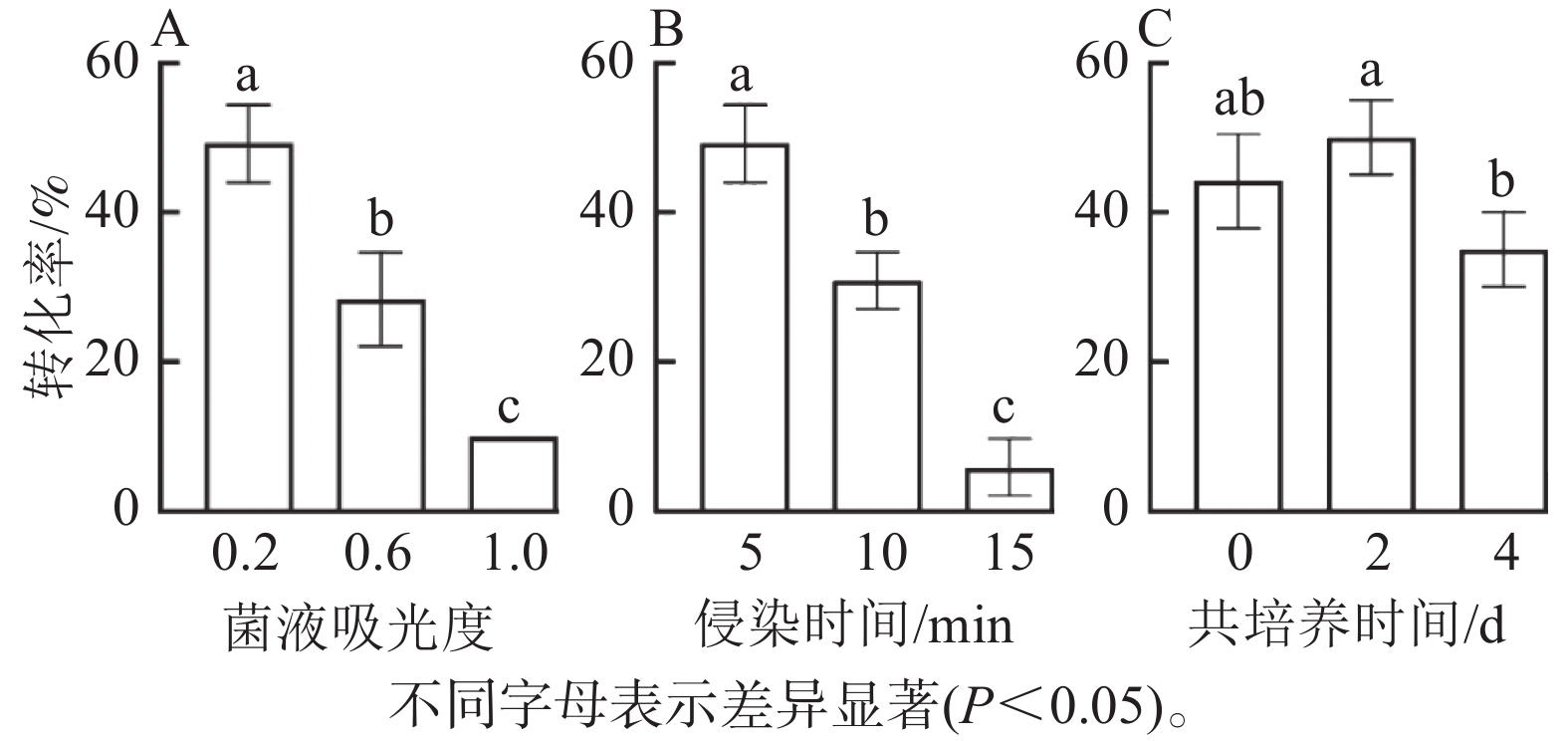

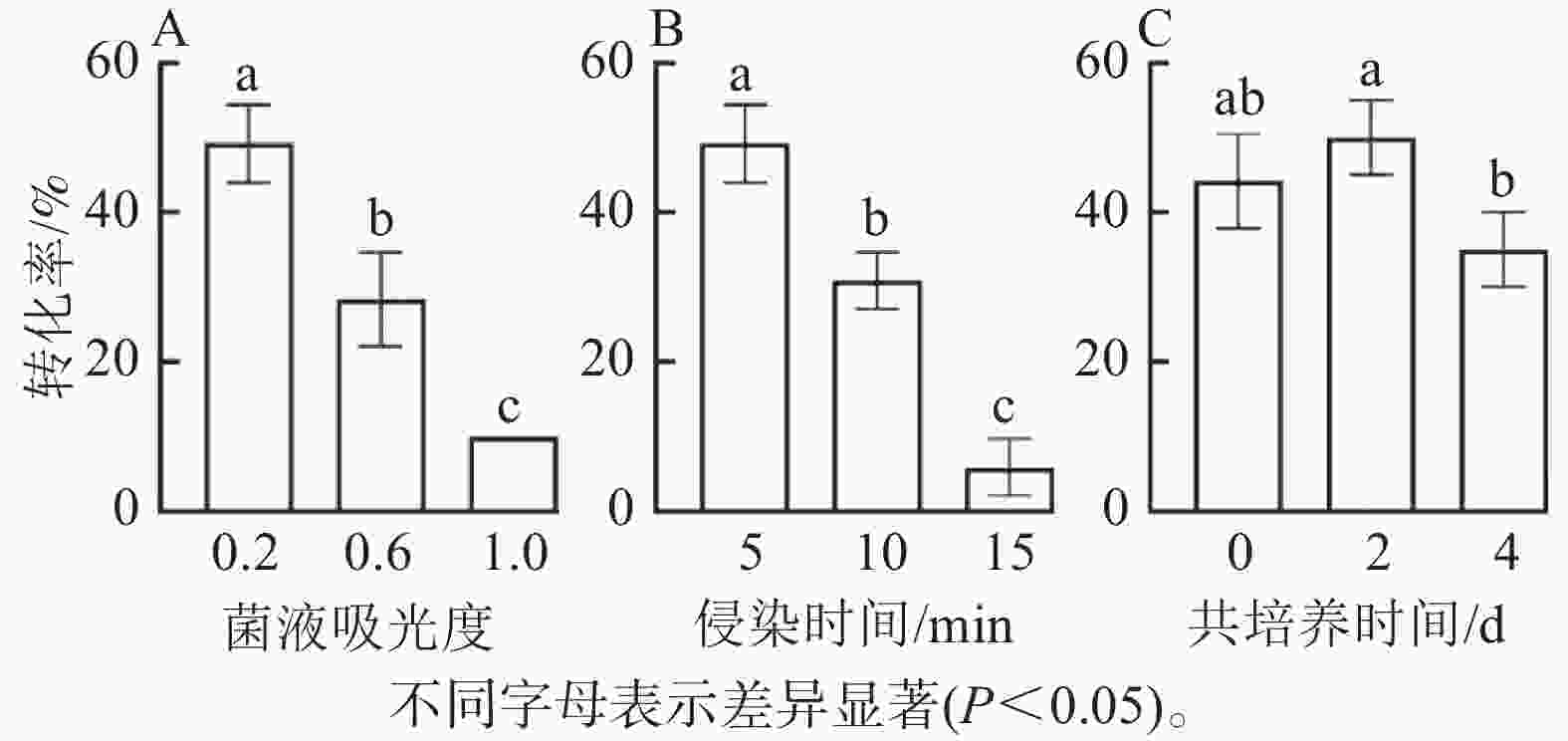

由图5可知:菌液D(600)=0.2时的转化率显著高于0.6和1.0时 (P<0.05),此时转化率最高(50%),随着D(600)的增加,转化率明显降低,可能由于较高的D(600)对叶盘产生了毒害作用(图5A);侵染时间为5 min时,转化率显著高于10和15 min,随着侵染时间的增加,转化率呈下降趋势(图5B);共培养2 d时,转化率最高,而较短的共培养时间和较长的共培养时间均导致转化效率降低,这是由于时间较短不利于基因与外植体整合,而时间较长会对叶盘造成伤害(图5C)。因此,菌液D(600)为0.2,侵染时间为5 min,共培养时间为2 d时,转化效率最高。

-

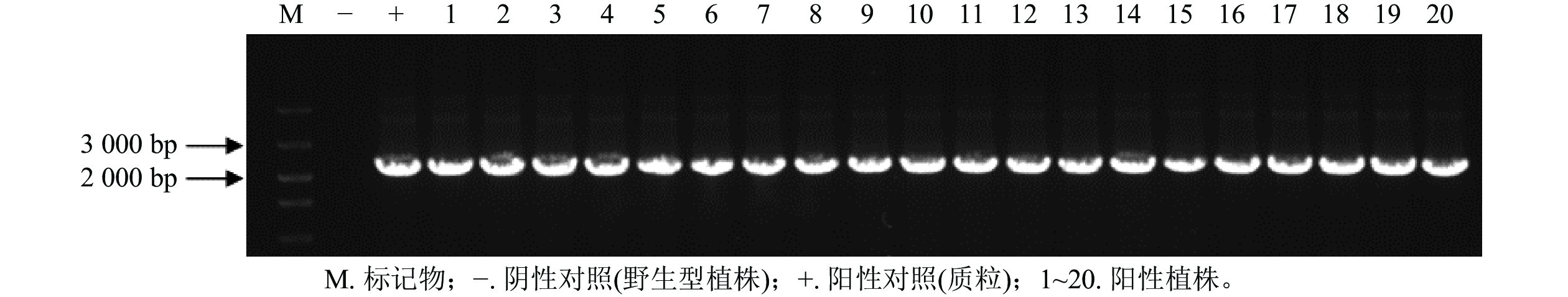

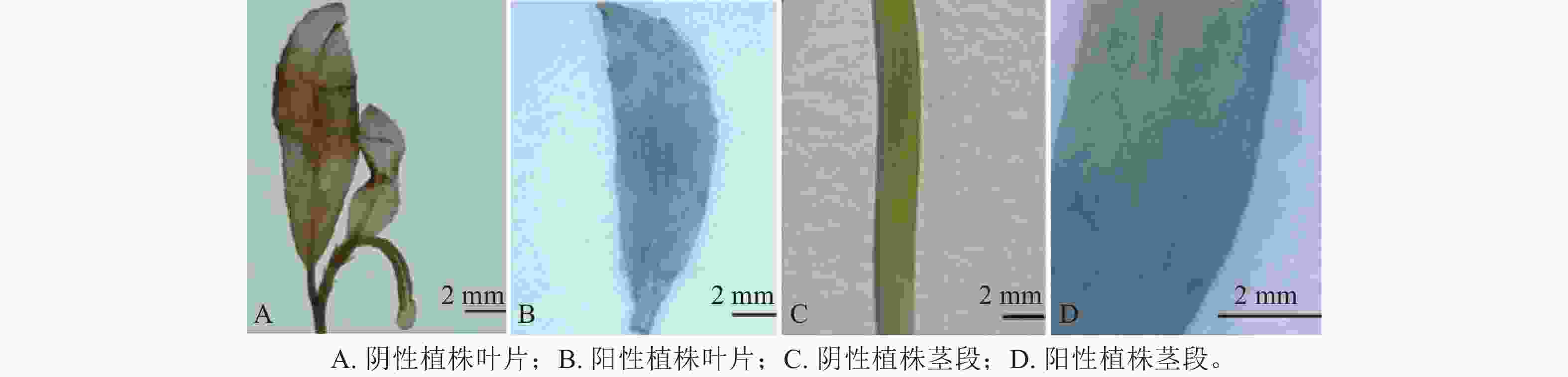

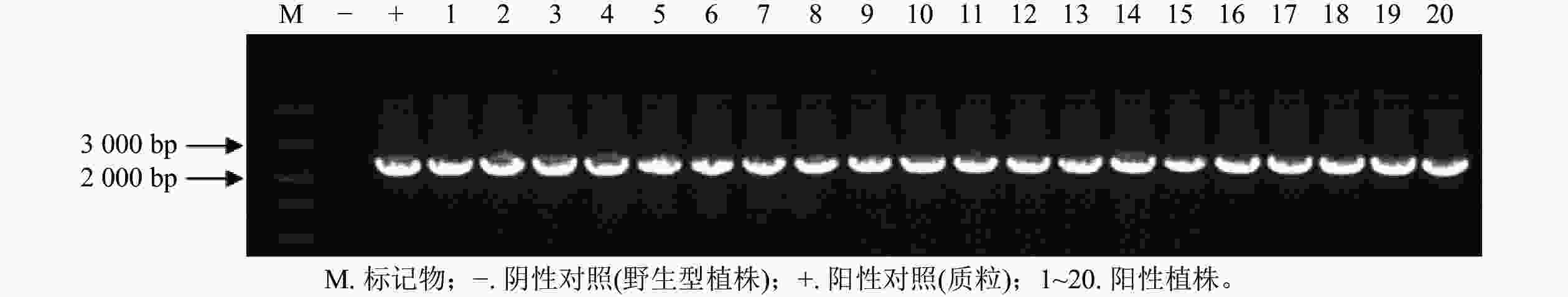

通过农杆菌转化共获得44株抗性植株,分别取抗性植株叶片和茎段进行GUS染色。图6表明:有20株的叶片和茎段均显蓝色,说明GUS基因已成功转入滇杨并且能顺利表达。进一步提取经GUS染色鉴定的基因组DNA,进行GUS基因(预期2 239 bp)的PCR扩增,结果显示:经染色鉴定为阳性的植株均可扩增出清晰的GUS基因条带(图7)。最终获得阳性植株20株,阳性率为45.45%。

-

杨树Populus作为乔木树种的模式植物,一些种的再生体系已得到广泛研究,其中辽宁杨P.×liaoningensis和河北杨P. hopeiensis在以叶片为外植体进行愈伤组织诱导和不定芽分化时,均以MS为最佳培养基[7−8],而大青杨P. ussuriensis和毛果杨P. trichocarpa则以WPM培养基较为适宜[9−10]。本研究采用MS为基本培养基时,滇杨叶片外植体褐化较严重,而1/2 MS基本培养基中的外植体呈嫩绿色,说明1/2 MS培养基适合滇杨叶片外植体的培养,该结果也与张春霞等[5]的研究结果一致。表明不同杨树种的外植体愈伤组织和不定芽生长所需要的无机元素和营养物质具有差异性[11−13]。

植物生长调节剂的种类和质量浓度对植物愈伤组织和不定芽的诱导至关重要[14−15]。本研究选取了不同质量浓度的TDZ和NAA进行组合添加至愈伤组织及不定芽诱导培养基中,发现TDZ质量浓度为0.005 mg·L−1时,叶盘的愈伤组织诱导率较高,而当TDZ质量浓度为0.001 mg·L−1时,愈伤组织诱导率较低。同时,适宜质量浓度的NAA (0.010 mg·L−1)与低质量浓度的TDZ (0.002 mg·L−1)对不定芽的诱导有明显的促进作用。该结果与乌日罕等[8]对河北杨的研究结果一致。此外,杨树不定芽的生根是其再生的关键步骤[16],青海青杨P. cathayana var. qinghai、胡杨P. euphratica和金叶杨P. nigra ‘Jinye’的最佳生根培养基为1/2 MS + IBA,生根率可达90%以上[17−19],而彭言劼等[20]筛选出大叶杨P. lasiocarpa的最适生根培养基为1/2 MS + NAA。辛培尧等[21]研究发现:滇杨不定芽在1/2 MS + 0.020 mg·L−1NAA生根培养基中进行培养,10 d开始生根。本研究在1/2 MS + 0.010 mg·L−1 NAA + 0.100 mg·L−1 IBA培养基中,不定芽提前至5 d开始生根,且根系粗壮,须根多,生根率高达96.7%。说明采用IBA与NAA的组合更有利于滇杨不定芽的生根诱导。

-

在卡那霉素抗性筛选中,发现当卡那霉素质量浓度为20 mg·L−1时,滇杨叶盘的生长受到严重抑制,而李春利等[22]研究表明:当卡那霉素质量浓度为30 mg·L−1时,毛白杨P. tomentosa愈伤组织不能分化形成不定芽。说明不同树种的不同受体材料对筛选剂的敏感度不同,因此选择合适的筛选剂质量浓度对获得转化植株至关重要[23]。此外,LI等[24]选用250 mg·L−1头孢霉素作为毛果杨的抑菌浓度。而本研究发现:200 mg·L−1头孢霉素就能完全抑制农杆菌生长,且对滇杨不定芽的生长影响较小。农杆菌质量浓度、侵染时间及共培养时间对植物的遗传转化效率起到重要作用[25−27]。本研究对这3个因素分析发现:当菌液吸光度为0.2,侵染时间为5 min,共培养为2 d时,最有利于滇杨的遗传转化,这与LI等[24]在毛果杨中的研究结果相似。

本研究以滇杨叶片为外植体,探讨了植物生长调节剂对叶片愈伤组织、不定芽诱导及其生根的影响,成功建立了滇杨离体叶片再生体系,并在此基础上,通过卡那霉素抗性筛选,利用农杆菌介导法从菌液吸光度、侵染时间和共培养时间开展了较为系统的研究,构建了滇杨的遗传转化体系。

Regeneration system and genetic transformation of Populus yunnanensis

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20230304

- Received Date: 2023-05-15

- Accepted Date: 2023-12-21

- Rev Recd Date: 2023-12-13

- Available Online: 2024-03-21

- Publish Date: 2024-04-01

-

Key words:

- Populus yunnanensis /

- leaf /

- callus /

- regeneration system /

- genetic transformation

Abstract:

| Citation: | ZHANG Xiaolin, ZONG Dan, LI Jiaqi, et al. Regeneration system and genetic transformation of Populus yunnanensis[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2024, 41(2): 314-321. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20230304 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: