-

紫杉醇(taxol)由美国化学家WANI等[1]于1971年在太平洋红豆杉Taxus brevifolia中发现。美国食品药品管理局(FDA)分别于1992、1994年批准了天然紫杉醇和基于10-去乙酰基巴卡亭Ⅲ(10-DAB Ⅲ)的半合成紫杉醇用于临床[2−3]。1998、2010年基于10-DAB Ⅲ半合成的多烯紫衫醇、卡巴他赛等抗癌药物用于临床[4]。这些药物的抗癌机制是选择性破坏微管、抑制有丝分裂等使癌细胞死亡,已被用于乳腺癌、卵巢癌、宫颈癌和前列腺癌等癌症的治疗[5−8]。红豆杉植物枝叶和树皮是天然紫杉醇和10-DAB Ⅲ的主要来源,但红豆杉植物中紫杉醇质量分数及提取率均极低。太平洋红豆杉树皮中紫杉醇质量分数为0.010 0%~0.080 0%,平均分离得率仅为0.014%~0.017%[9]。紫杉醇在云南红豆杉T. yunnanensis和东北红豆杉T. cuspidata树皮中质量分数为0.005 0%~0.030 0%,枝叶中质量分数0.001 3%~0.013 7%[10]。随着紫杉醇及其他半合成紫杉烷类药物如多烯紫衫醇、卡巴他赛等的广泛应用,仅从红豆杉植物中提取的紫杉醇已经不能满足日益增长的医药市场需求,而合成其他紫杉烷类药物需要大量的10-DAB Ⅲ。虽然已经对从生物催化合成和从红豆杉植物的内生菌中发现紫杉烷类化合物及从内生菌中的分离10-DAB有所研究,但离产业化需要仍有距离[11−12]。以紫杉醇质量分数为红豆杉中3~10倍的10-DAB Ⅲ 作为原料进行半合成是目前生产紫杉醇及其他紫杉烷类药物的主要途径。1988年DENIS等[13]报道了有效获取天然紫杉醇的方法。半合成、全合成方法由OJIMA等[14]和HOLTON等[15]在1992年和1994年进行报道。从红豆杉植物中提取10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇对后续采用10-DAB Ⅲ半合成紫杉醇及其他紫杉烷类药物具有重要意义。

植物活性物质提取是指应用溶剂浸提法将植物中的可溶性组分提取出来的过程,常采用静态和搅拌提取2种方式。以往的植物成分提取多集中于从工艺角度进行比较研究,确定最佳工艺,很少涉及从传质及动力学角度进行深入探讨。粒径较小时搅拌提取优于微波辅助提取,具有操作简便省时、高效、节能的特点[16]。机械搅拌辅助提取因其方便快速、提取率高等优点被广泛应用在天然产物的提取。机械搅拌辅助提取可以结合罐组式逆流提取,具有溶媒和能源用量少,药材受热均匀、受热时间短,有效成分转移率高,可不间断连续生产,可更好地保留热敏性有效成分等优点[17−18]。对于这种基于搅拌辅助提取连续工业化的提取设计,传质规律研究更具有现实意义。

随着提取工艺的不断优化,红豆杉植物中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取过程动力学研究对紫杉烷类化合物工业化生产具有重要意义,目前尚未见关于云南红豆杉10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇提取动力学相关报道。本研究通过分析机械搅拌辅助和水浴加热提取紫杉烷类化合物过程中的动力学、菲克第二扩散定律和热力学,估算提取过程中的活化能、热力学参数、扩散系数、传质系数和毕奥数,并使用标准差和相关系数表示动力学模型与实验动力学数据的拟合状况,进一步阐述植物成分提取的传质机制,为相关植物功能成分的提取研究和工业化生产提供理论基础。

-

仪器包括AC Chrom S6000型高效液相色谱分析仪(北京华谱新创科技有限公司)、600Y型多功能粉碎机(广州旭朗机械设备有限公司)、W2S型升降恒温水浴锅(巩义市英裕高科仪器厂)、JJ-1型精密增力电动机械搅拌器(常州国华电器有限公司)、BS223S型电子天平(北京赛多利斯仪器系统有限公司)、KQ-500B型超声波清洗器(巩义市英裕高科仪器厂)。

材料分别为10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇标准品(纯度≥99%)购于西安天丰生物科技有限公司;乙腈(色谱纯)、甲醇(纯度≥98%)购于天津康科德科技有限公司;乙腈(分析纯)、甲醇(分析纯)购于天津市科密欧化学试剂有限公司;云南红豆杉枝叶采自云南保山市。

-

将云南红豆杉枝叶在粉碎机中粉碎和筛分,原料粒度为150~250 μm。过筛后的原料在50 ℃烘箱中干燥至恒量并保存于玻璃干燥器中。

-

采用C18色谱柱(4.6 mm×250 mm,5 μm)进行分析,流动相A为乙腈,流动相B为超纯水。梯度洗脱程序如下:0~20 min:15%~50%A;20~50 min:50%~100%A;50~65 min:100%A;65~67 min:100%~15%A;67~80 min:15%A。百分数均为体积分数,流动相流速为0.8 mL·min−1,检测波长为227 nm,柱温为30 ℃,进样量为10 μL。

-

称取适量10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇标准品溶于甲醇,配制不同质量浓度梯度的标准溶液,用0.22 μm微孔滤膜过滤,采用高效液相色谱-二极管阵列检测器(HPLC-DAD)测定并得到10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇标准曲线。10-DAB Ⅲ标准曲线的回归方程为:y=1.798×107x+2.353×105,R2=0.998 9;紫杉醇标准曲线的回归方程为:y=2.707×107x+1.649×103,R2=0.999 8。其中:x为标准品质量浓度(mg·mL−1);y为采用HPLC-DAD测得的峰面积(mV·s),分别用于后续液体提取物中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇质量浓度的测定。

云南红豆杉枝叶中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的质量浓度经液相分析和标准曲线方程计算。公式如下:

式(1)~(2)中:C1为样品质量浓度(mg·mL−1);C2为标准品质量浓度(mg·mL−1);A1为样品峰面积(mV·s);A2为标准品峰面积(mV·s);M为样品总量(mg);V为样品体积(mL)。

-

称取50 g云南红豆杉原料加入250 mL甲醇,设定电动搅拌器转速为136 r·min−1,以1∶5料液比进行机械搅拌辅助提取,在搅拌提取时间为2~120 min,提取溶剂甲醇沸点为64.7 ℃,提取温度分别为15、35、55 ℃。提取液中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇质量浓度通过标准曲线计算得到。

-

称取5 g云南红豆杉于250 mL锥形烧瓶中,以云南红豆杉滞液量1.7 mL·g−1甲醇浸润,以1∶10料液比进行水浴提取,并控制提取时间为5~240 min,提取溶剂甲醇沸点为64.7 ℃,提取温度分别为35、45、55 ℃。提取液中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇质量浓度通过标准曲线计算得到。

-

参照文献[19−20],基于一阶动力学模型和二阶动力学模型分别对2种云南红豆杉枝叶中紫杉烷类物质的提取动力学进行研究。一阶提取模型公式(3)可写成公式(4);二阶提取模型公式(5)可以写成公式(6),也可以写成如公式(7)所示线性形式。具体公式如下:

式(3)~(7)中:Ct为时间t (s)云南红豆杉提取物溶液中紫杉烷类物质的质量浓度(mg·mL−1);$ {C}_{0} $为云南红豆杉提取物溶液中紫杉烷类物质的初始质量浓度(mg·mL−1); C∞、$ {C}_{\mathrm{e}} $为一阶提取模型和二阶提取模型紫杉烷类物质的平衡质量浓度(mg·mL−1);t为时间(s);k1为一级速率常数(s−1);k2为二级速率常数(mL·mg−1·s−1),提取速率常数受温度的影响。

根据Arrhenius方程可以推导出热量与提取速率常数之间的关系,利用公式(8)计算活化能[21]。

式(8)中:k为提取速率常数(mL·mg−1·min−1);Ea为活化能(kJ·mol−1);T为温度(K);R为通用气体常数(8.314 J·mol−1·K−1);$ {k}_{0} $为指前因子,也称为频率因子。

-

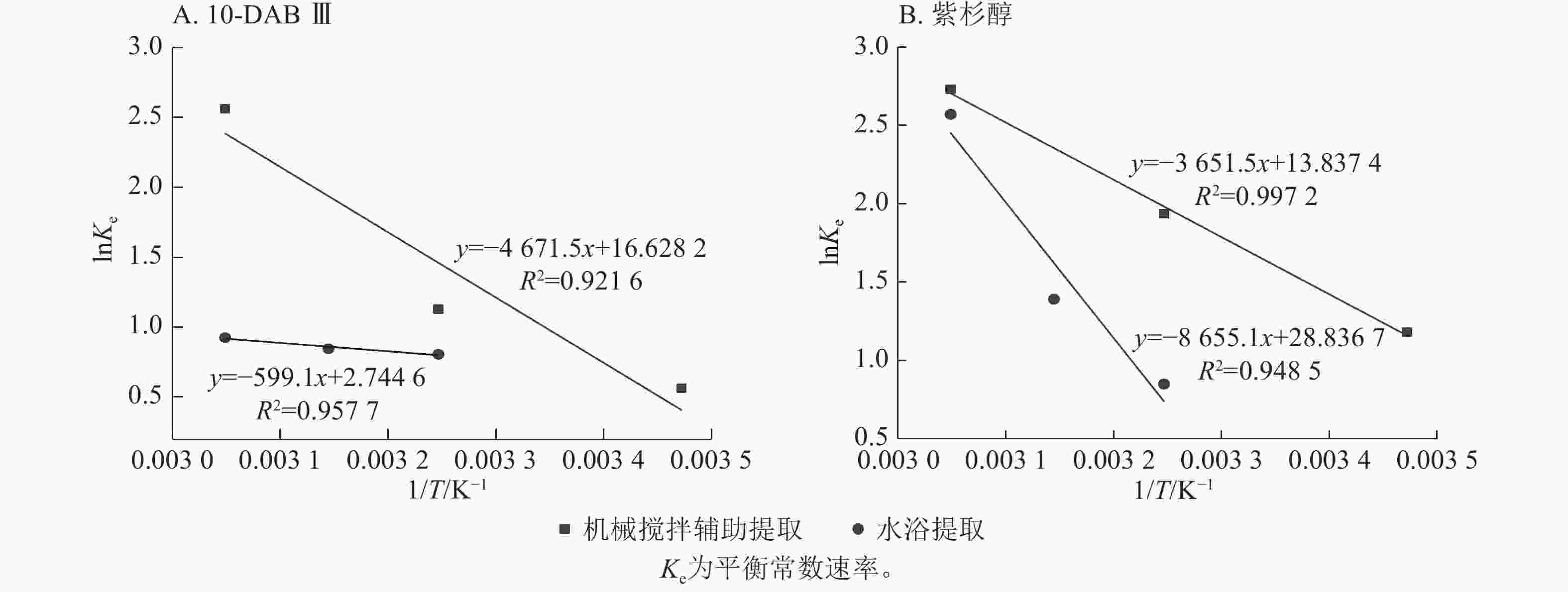

热力学参数对于确定反应发生的能量变化至关重要。应用Van’t Hoff方程计算化合物的标准焓和标准熵,确定化学提取过程,在恒温恒压的热力学系统中计算基本组分所得吉布斯自由能。焓(ΔH,kJ·mol−1)和熵(ΔS,kJ·mol−1·K−1)的由公式(9)通过绘制平衡常数速率(lnKe)与温度(1/$ T $)之间的曲线计算得到。吉布斯自由能(ΔG)由公式(10)计算[21]:

式(9)~(10)中:Ke是平衡常数速率,即已提取的紫杉烷类物质质量浓度与未提取的残留紫杉烷类物质质量浓度的关系[21]:

式(11)中:Ys为饱和10-DAB Ⅲ或紫杉醇产量(mg·g−1);Ymax为最大10-DAB Ⅲ或紫杉醇产量(mg·g−1)。

-

基于以下假设[22]和Fick第二定律扩散模型研究10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的有效扩散系数。①10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取被认为是由细胞壁中10-DAB Ⅲ、紫杉醇的快速溶解和溶质从固体颗粒缓慢扩散到提取液中的2步过程。②10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇最初均匀地包含在对称的球体固体中,粒子平均直径为200 μm。③10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇分子的转运是一种扩散现象。它由恒定的且与时间无关的扩散系数(D)描述。10-DAB Ⅲ、紫杉醇和其他化合物的扩散是同时发生且没有相互作用的。④在机械搅拌器的帮助下溶液是完全紊流和混合的。忽略液相中传质阻力,10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的质量浓度仅取决于时间。⑤在界面处,假设孔隙中液体与外部溶液的溶质平衡质量浓度相等。⑥水浴提取实验的平衡质量浓度是用时间为240 min来计算的。机械搅拌提取的10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇化合物无降解现象。

固体和液体提取过程中的毕奥数(Biot)是确定和验证传质内外部阻力相对量的主要方法[23]。球形颗粒提取化合物根据Fick第二定律。

式(12)中:M为云南红豆杉颗粒中紫杉烷类化合物的质量浓度(kg·m−3);r为云南红豆杉颗粒与球形红豆杉颗粒中心的距离(m);De为紫杉烷类化合物的有效扩散系数;t为时间(s)。

参考文献[24],公式(12)在初始条件和边界条件下的解分别见公式(13)和(14):

式(13)~(14)中:Ys为饱和目标化合物产量(mg·g−1);Yt为t时刻的目标化合物产量(mg·g−1);rp为颗粒半径(m);De为扩散系数(m2·s−1)。

Biot根据公式(15)计算。传质系数根据各温度值下ln[C∞/(C∞-Ct)]与时间的关系应用公式(16)计算[25]:

式(15)~(16)中:KT为传质系数(m·s−1);A为粒子总表面面积(m2);Vs为溶液体积(m3)。

-

使用WPS 2021处理数据,采用SPSS 22进行单因素分析(one-way ANOVA)和多重比较(邓肯法),显著性水平为0.05,使用Origin 2017作图。

-

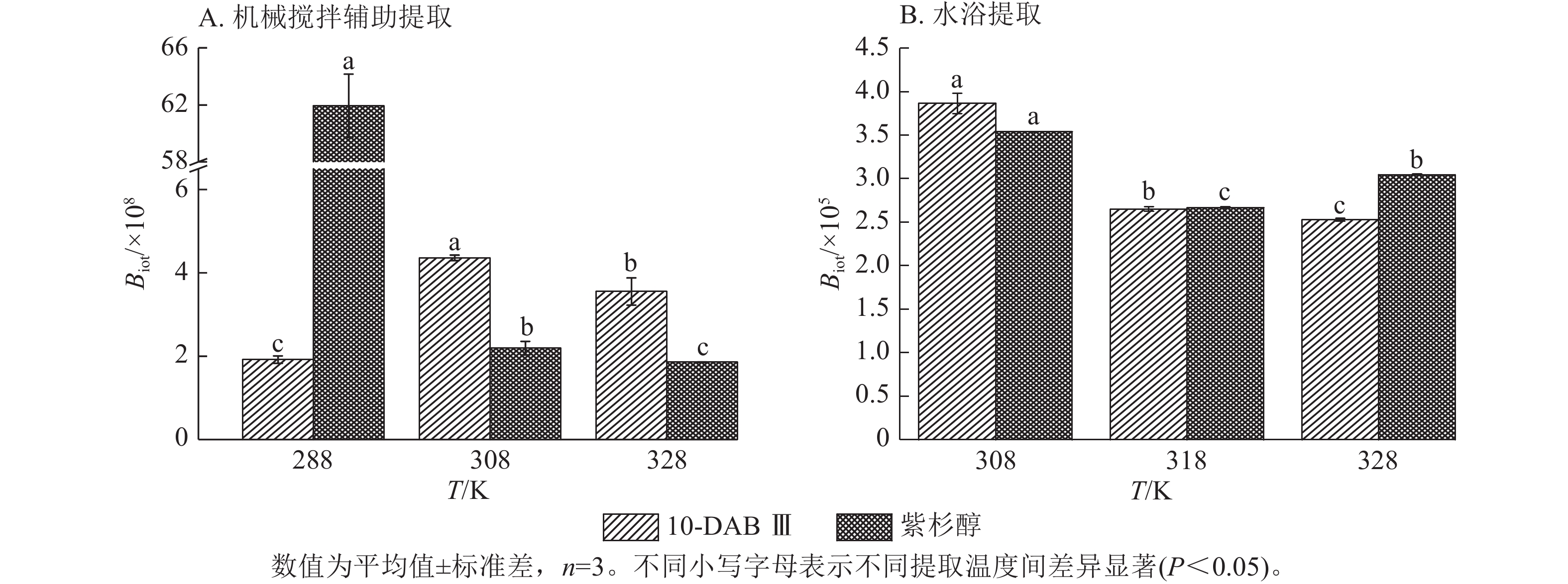

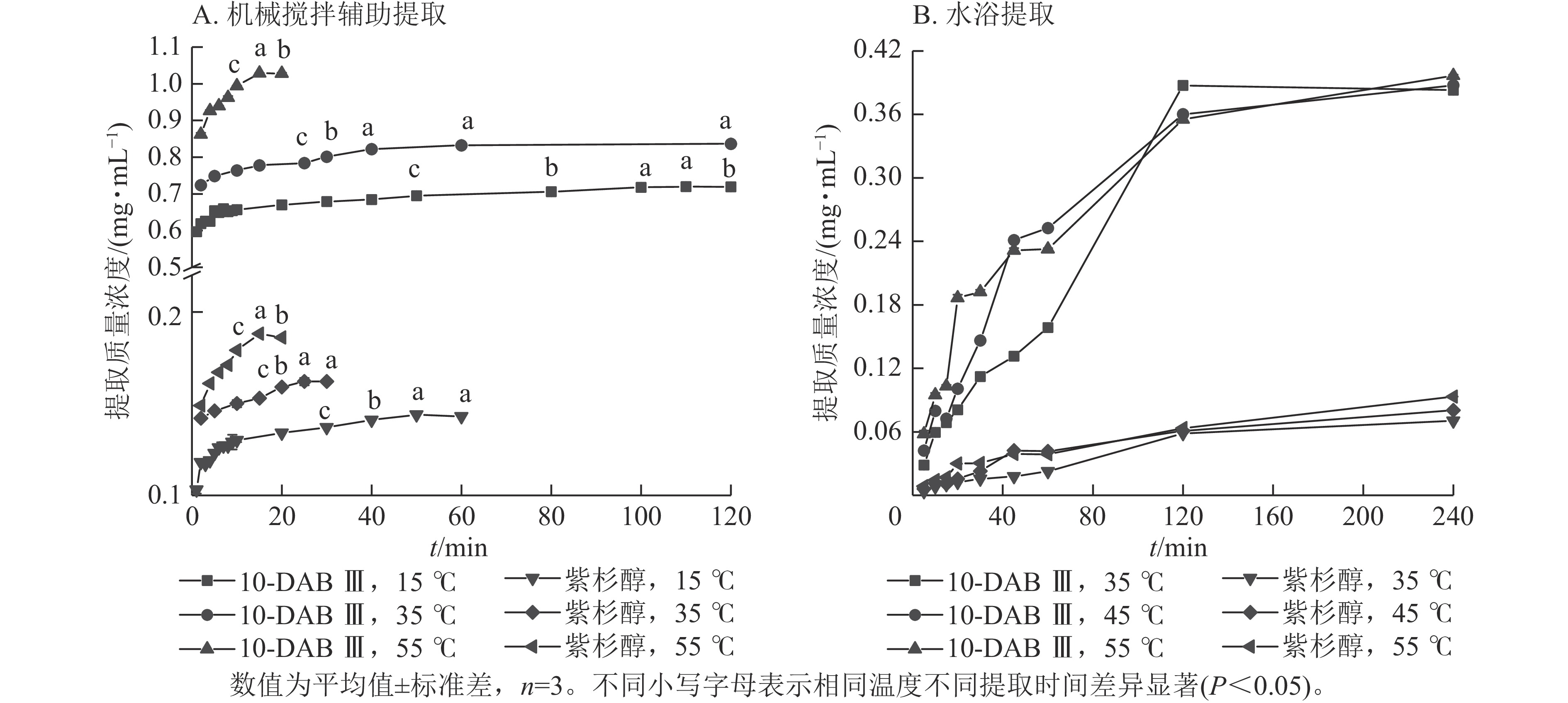

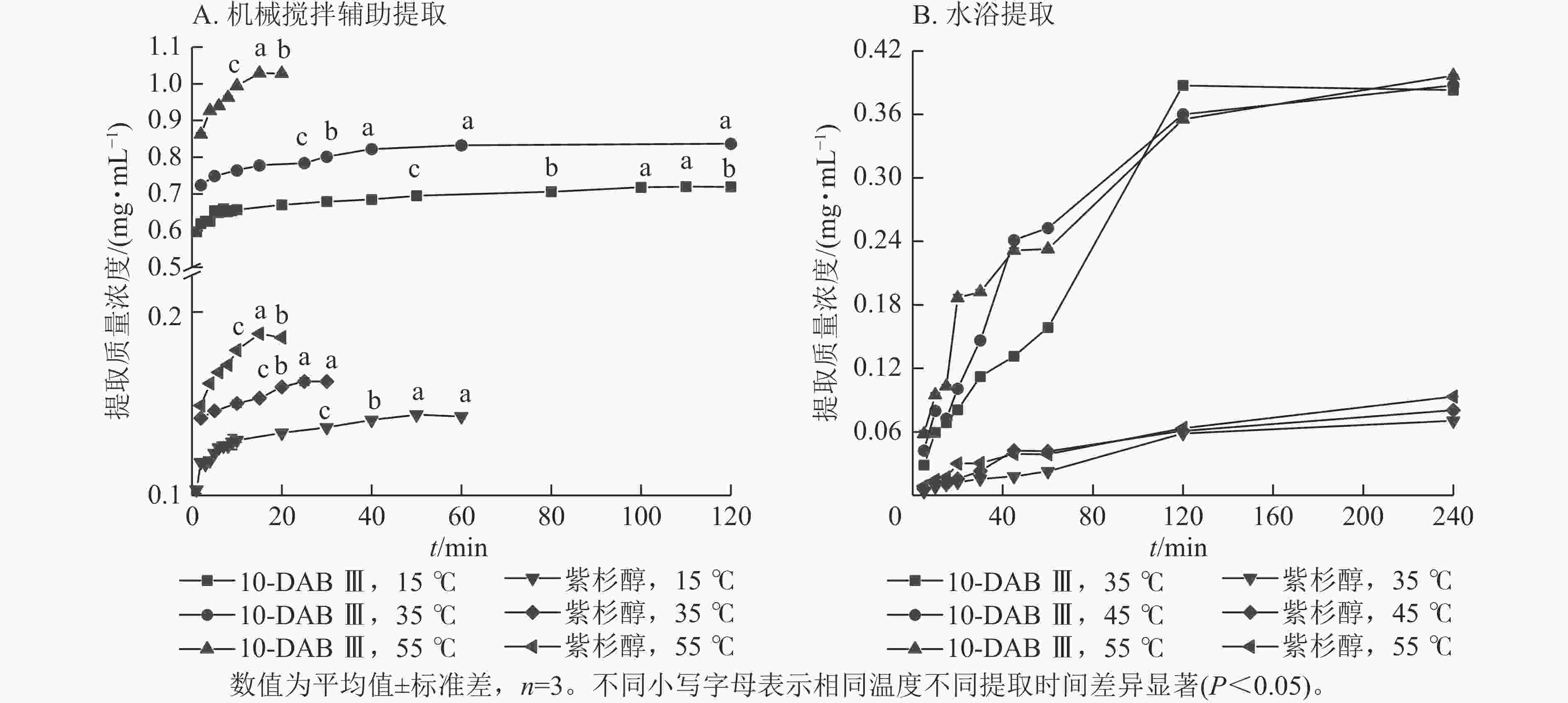

从图1A可以看出:机械搅拌辅助提取在3种提取温度下,10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取平衡时间分别为90、40、15 min和50、25、15 min。快速提取期均在10 min内,且提取温度为55 ℃时,提取质量浓度最高。10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取平衡时间随提取温度的升高而明显缩短,提取质量浓度随提取时间增加、提取温度的升高而增加,直到达到饱和阶段。

-

从图1B可以看出:在水浴条件下,10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的快速提取期为0~45 min,且提取速率随提取温度的升高而加快。提取速率随温度升高而提高是由于10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇溶解度随温度升高而增加。此外,10-DAB Ⅲ和Taxol提取平衡时的质量浓度随提取温度的升高而增大。

-

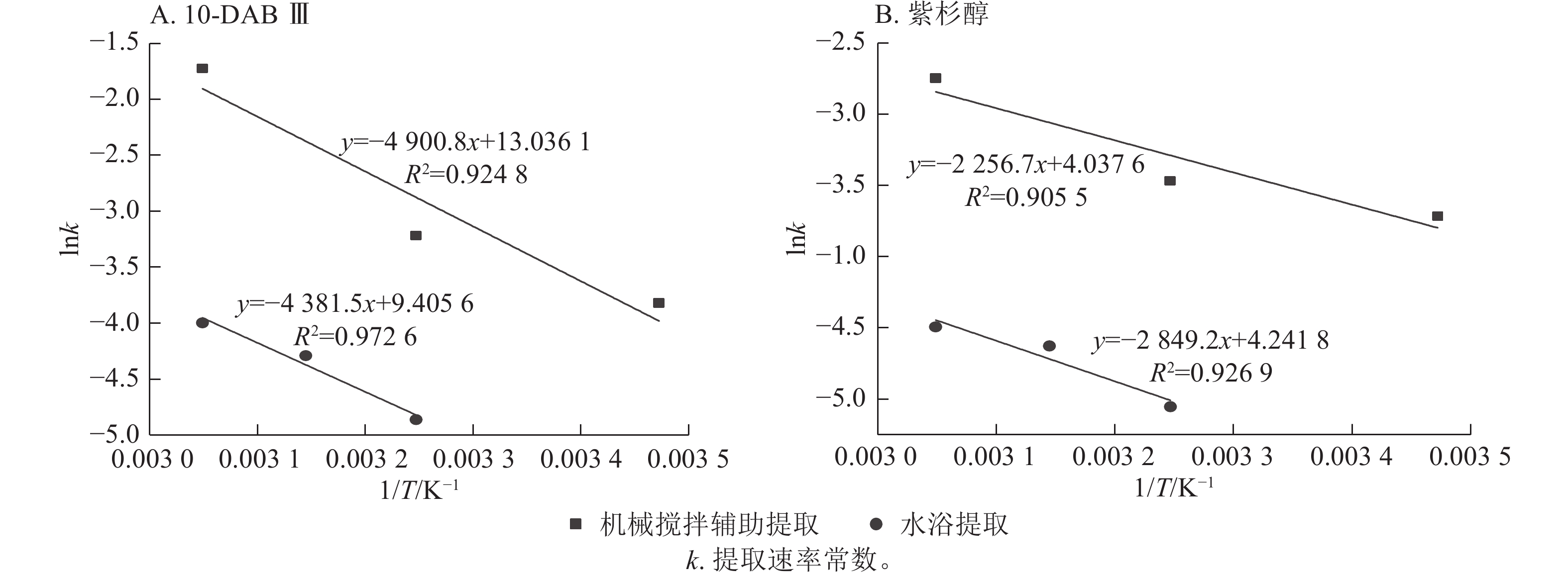

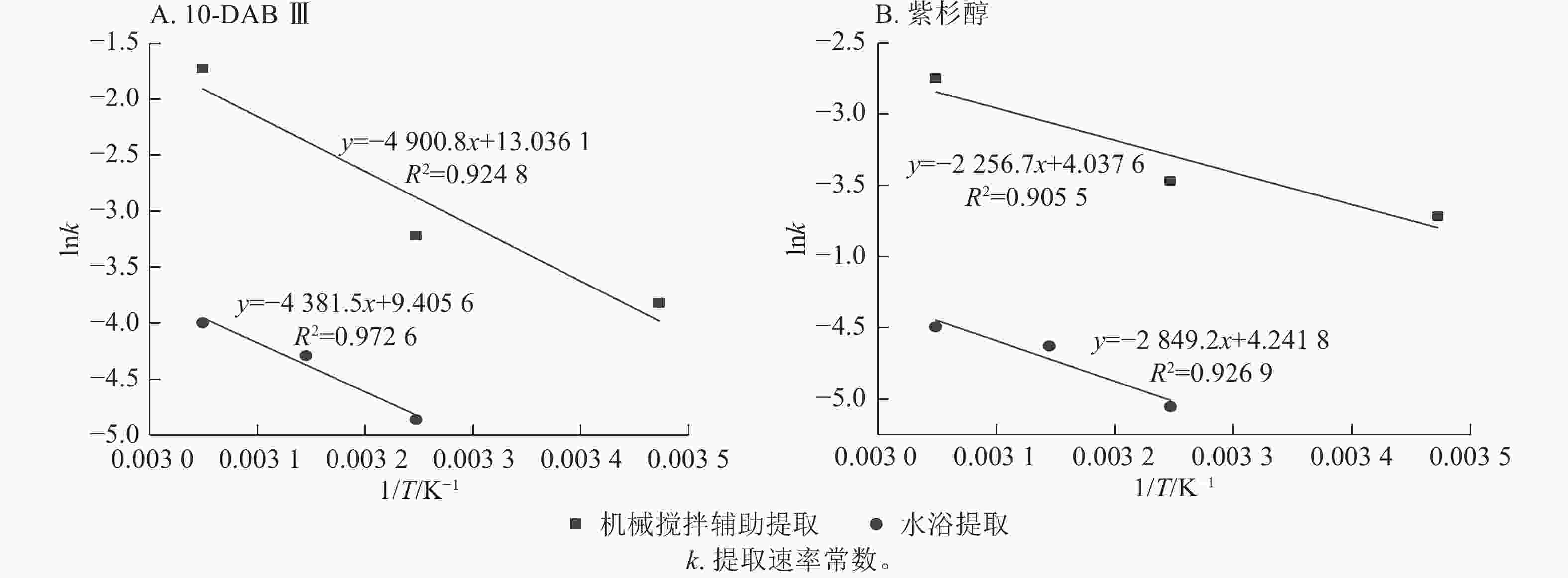

公式(8)中的提取速率常数可用于表示提取时溶质转移必须克服的能垒的活化能,活化能的主要来源是溶质-溶质内聚和溶质-固体黏附相互作用。较高温度下溶质-溶质和溶质-固体的相互作用变弱导致提取速率常数(k)增加[26]。图2显示了10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇在2种提取中lnk与绝对温度(1/T)的倒数关系。

Figure 2. Determination of activation energy of taxane compounds in mechanical stirring extraction and water bath extraction using Arrhenius equation

由图2A可知:2种提取方式下,10-DAB Ⅲ的活化能分别为40.745和36.428 kJ·mol−1。由图2B可知:2种提取方式下,Taxol的活化能分别为18.762和16.668 kJ·mol−1。本研究结果与KIM等[27]发现紫杉醇活化能为16.827 kJ·mol−1的结果基本一致。没发现有关10-DAB Ⅲ活化能的研究。

为进行动力学分析,将数据应用于一阶和二阶动力学模型,并计算活化能。由表1显示:二阶动力学模型更适合机械搅拌辅助提取方式。与此同时,水浴提取符合一阶动力学模型,因有大量的底物为使其浓度与其他物质浓度保持恒定时发生。

提取方法 紫杉烷类化合物 T /℃ 料液比 一阶动力学模型 二阶动力学模型 k1/min R2 活化能/(kJ·mol−1) k2/(×10−5 L·mg−1·s−1) R2 机械搅拌辅助提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 15 1∶5 0.022±0.002 0.958 40.745±1.855 1.860±0.046 0.999 8 35 0.040±0.002 0.967 1.947±0.073 0.999 7 55 0.178±0.002 0.950 2.641±0.026 0.999 5 紫杉醇 15 0.024±0.002 0.982 18.762±1.211 5.676±0.051 0.997 0 35 0.031±0.001 0.996 6.445±0.233 0.999 0 55 0.064±0.000 0.982 7.538±0.016 0.998 0 水浴提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 35 1∶10 7.744±0.089 0.979 36.428±0.282 7.273±0.353 0.970 0 45 13.723±0.028 0.931 8.785±0.008 0.962 0 55 18.388±0.091 0.988 14.319±0.528 0.986 0 紫杉醇 35 7.537±0.012 0.956 16.668±0.256 0.300± 0.0001 0.923 0 45 9.792±0.011 0.950 0.315± 0.0001 0.958 0 55 11.201±0.009 0.996 0.348± 0.0004 0.949 0 说明:k1为一级速率常数;k2为二级速率常数。 Table 1. Kinetic parameters of extraction of taxane compounds by mechanical stirring-assisted and water bath

-

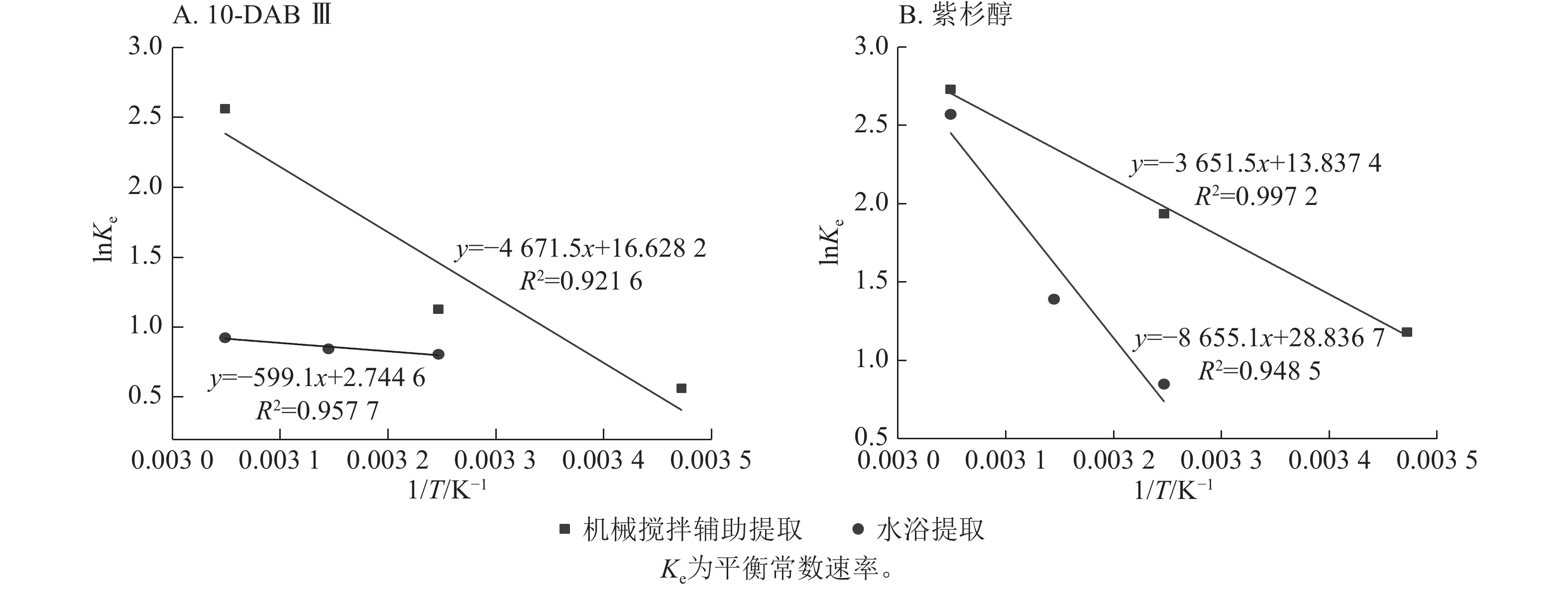

由表2可见:平衡常数随提取温度的升高而增大,与图3显示的结果一致。焓变值和熵变值均为正值,表示2种提取过程是吸热且随机湍流的。这是由于溶质(10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇)在分子的介质中从固态转移过程中部分被安排到有序度较低的液态溶剂中导致湍流的增加[23]。另一方面,吉布斯自由能的负值表明2种提取过程均是自发的。

提取方法 紫杉烷类化合物 T /℃ 料液比 Ke ΔH/(kJ·mol−1) ΔS/(J·mol−1·K−1) ΔG/(kJ·mol−1) R2 机械搅拌辅助提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 15 1∶5 1.756±0.001 38.840±0.305 138.240±1.034 −0.976±0.007 0.922 35 1∶5 3.088±0.005 −3.741±0.013 55 1∶5 12.977±0.299 −6.506±0.034 紫杉醇 15 1∶5 3.256±0.053 30.359±0.186 115.045±0.460 −2.774±0.044 0.997 35 1∶5 6.926±0.207 −5.075±0.044 55 1∶5 15.330±0.094 −7.376±0.035 水浴提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 35 1∶10 2.240±0.003 4.981±0.031 22.819±0.087 −1.591±0.006 0.958 45 1∶10 2.331±0.004 −2.047±0.004 55 1∶10 2.523±0.002 −2.504±0.002 紫杉醇 35 1∶10 2.338±0.002 71.958±0.291 239.765±0.942 −1.889±0.001 0.949 45 1∶10 4.019±0.005 −4.287±0.009 55 1∶10 13.068±0.101 −6.685±0.018 说明:Ke为平衡常数速率;ΔH为焓变;ΔS为熵变;ΔG为Gibbs自由能变化。 Table 2. Thermodynamic parameters of extraction of taxanes by mechanical stirring-assisted and water baths

-

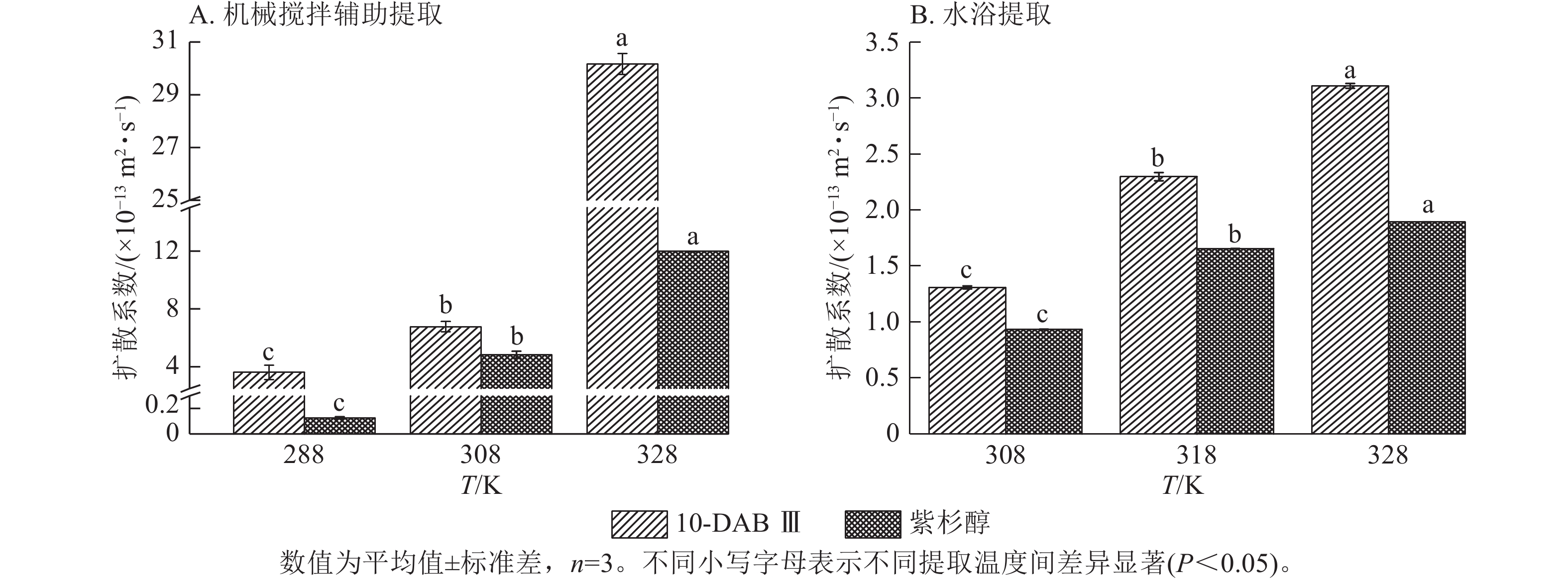

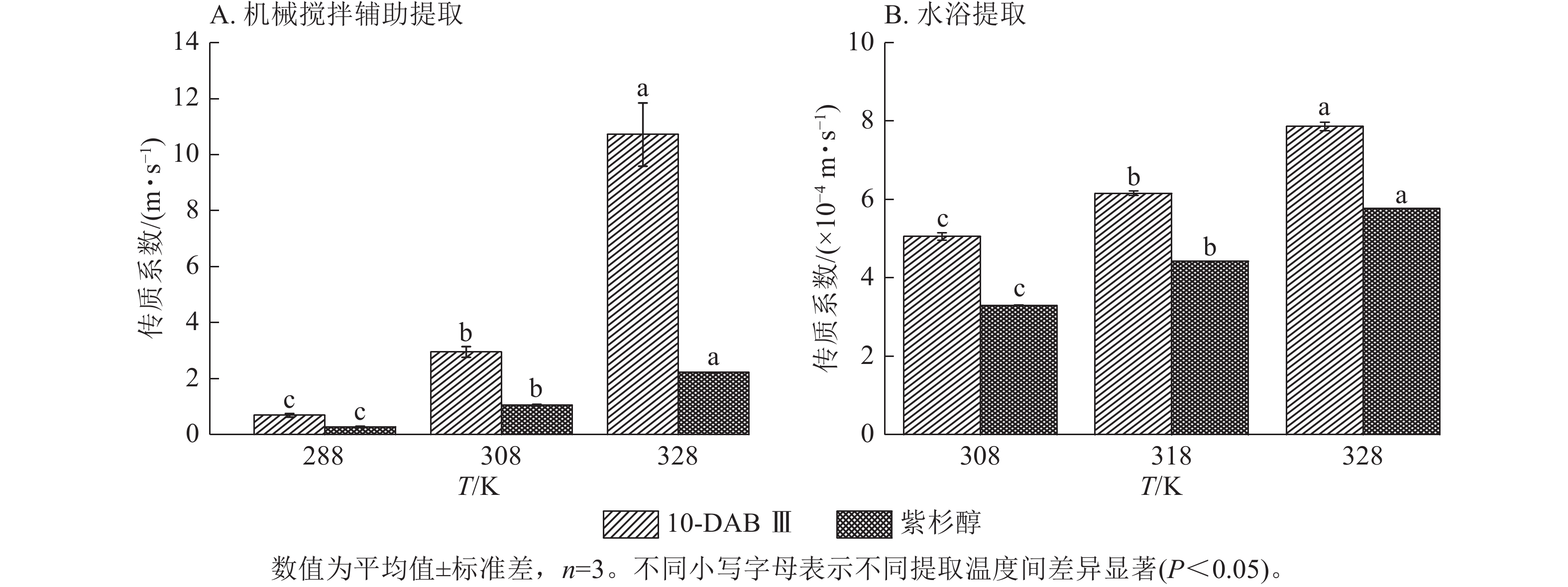

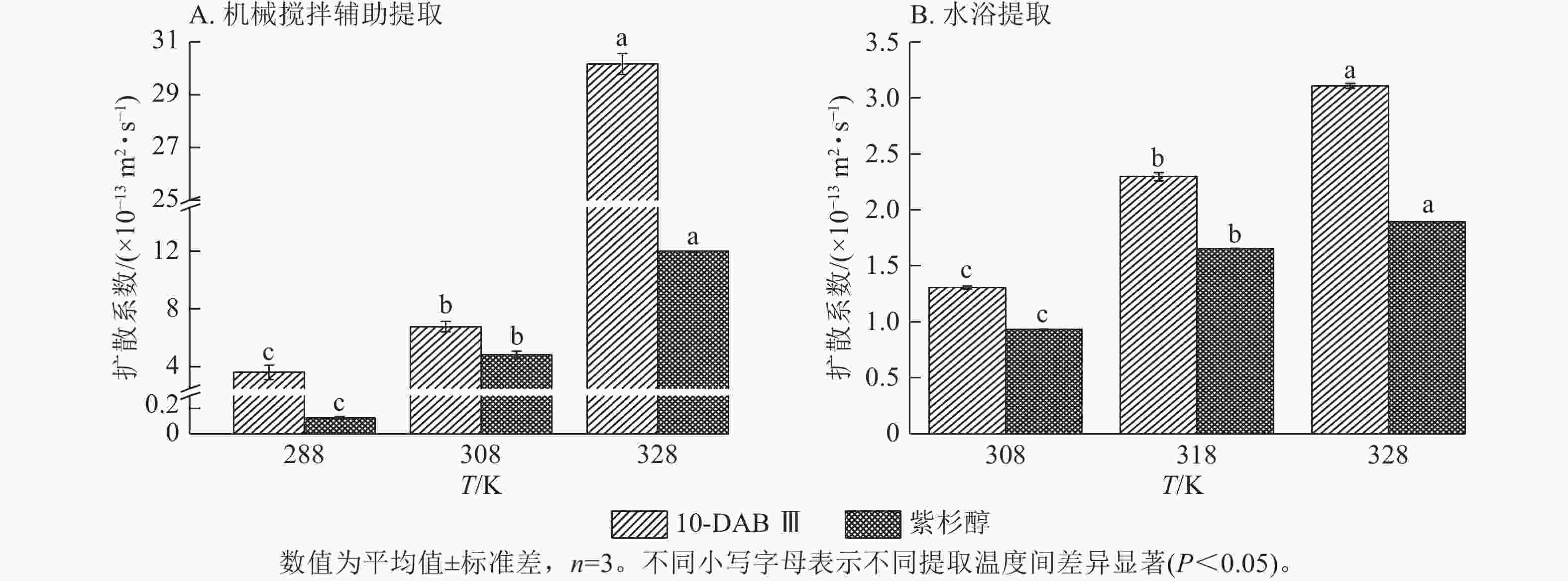

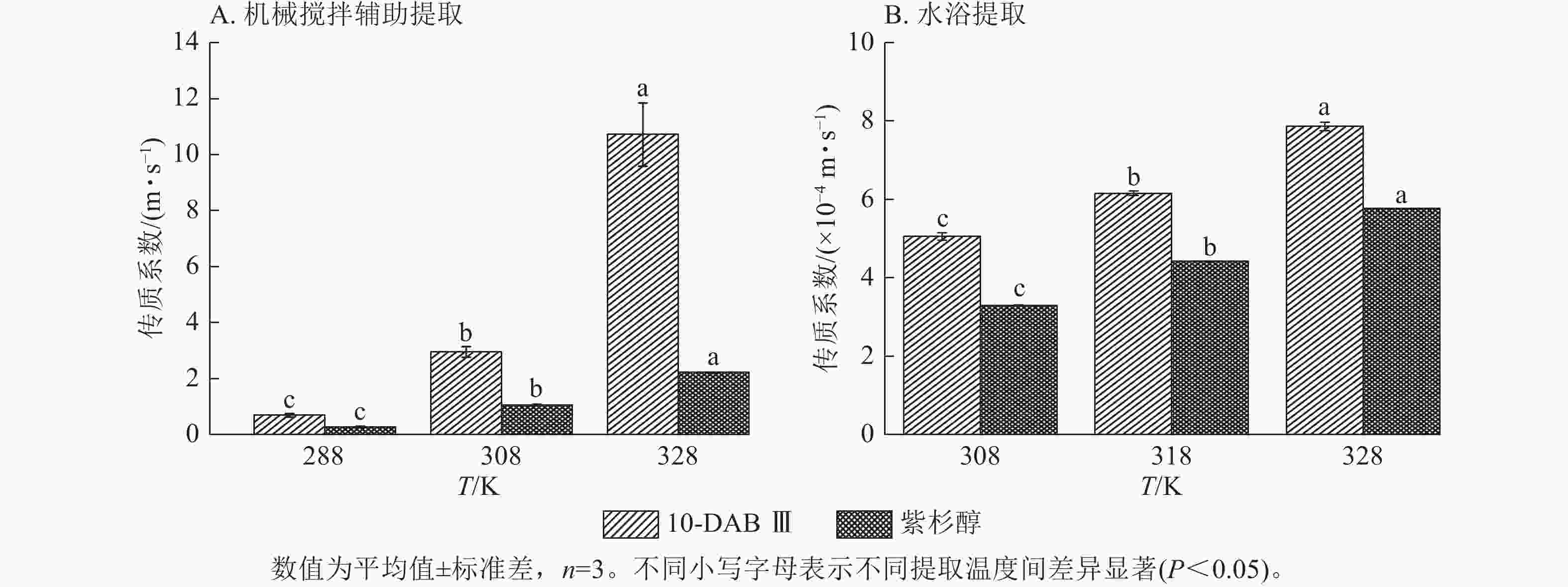

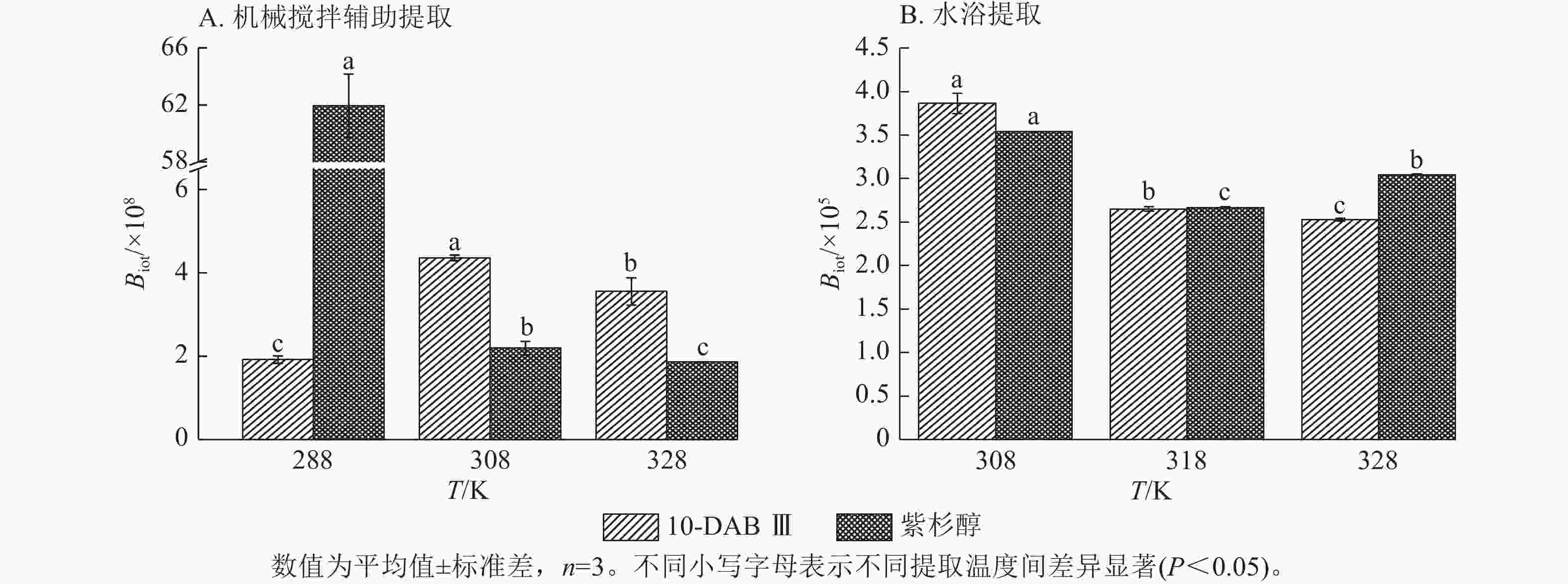

为了验证和描述传质扩散过程的机理,需要计算扩散系数(De)、传质系数(KT)和Biot。图4~6显示:当提取温度从288 K升高到328 K时,机械搅拌提取10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇过程中扩散系数和传质系数显著增加(P<0.05),均高于水浴提取。机械搅拌提取和水浴提取云南红豆杉10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇过程中Biot呈现下降趋势,扩散系数和传质系数随提取温度的升高而增大。可见提取温度的升高有利于云南红豆杉中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇在溶剂中的溶解。

Figure 4. Relationship between diffusion coefficient and temperature during the extraction process of taxane compounds

Figure 5. Relationship between mass transfer coefficient and temperature during the extraction process of taxane compounds

Figure 6. Relationship between Biot and temperature during the extraction process of taxane compounds

如表3所示:热能随温度的升高而增加,2种提取方法提取10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的扩散系数均随温度的升高而增大。紫杉烷类化合物从云南红豆杉颗粒外表面转移到溶剂的传质过程取决于溶剂的黏度、扩散系数和温度,传质过程中固液反应黏度随温度的升高而变大,进而导致传质系数减小。提取温度的升高和传质系数的增加是扩散系数和黏度增加的综合作用结果[28]。可以解释温度对传质系数的影响小于对扩散系数的影响。由公式(14)可知:Biot主要取决于扩散系数、粒径和传质系数。Biot大于100表明传质的外部阻力远低于内部阻力。以上结果说明:云南 红豆杉中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取过程主要受内部阻力影响[29]。在固液萃取过程中,内扩散控制提取紫杉烷类物质是控制提取的主要阶段。此外,机械搅拌辅助提取相较于水浴提取的Biot增加也表明搅拌可以显著消除外扩散阻力。

提取方法 提取物 提取温度/℃ 料液比 De/(×10−13 m2·s−1) Biot/×108 KT/(m·s−1) 机械搅拌辅助提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 15 1∶5 3.616±0.495 1.919±0.088 0.692±0.063 35 1∶5 6.770±0.351 4.361±0.065 2.953±0.197 55 1∶5 30.169±0.394 3.551±0.328 10.720±1.129 紫杉醇 15 1∶5 0.127±0.008 61.933±2.211 0.283±0.021 35 1∶5 4.833±0.251 2.191±0.163 1.057±0.024 55 1∶5 11.972±0.011 1.859±0.002 2.225±0.005 提取方法 提取物 提取温度/℃ 料液比 De/(×10−13 m2·s−1) Biot/×105 KT/(×10−4m·s−1) 水浴提取 10-DAB Ⅲ 35 1∶10 1.308±0.014 3.865±0.116 5.057±0.097 45 1∶10 2.297±0.036 2.650±0.027 6.155±0.062 55 1∶10 3.109±0.022 2.528±0.018 7.857±0.110 紫杉醇 35 1∶10 0.933±0.003 3.539±0.003 3.300±0.007 45 1∶10 1.655±0.002 2.669±0.006 4.417±0.006 55 1∶10 1.894±0.002 3.048±0.006 5.771±0.007 说明:De. 扩散系数;KT. 传质系数。 Table 3. Diffusion coefficient, mass transfer coefficient, and Biot value of taxane compounds extracted with mechanical stirring assistance and water bath

-

植物成分提取动力学研究是指导工业生产的理论基础。植物活性成分提取的动力学模型大部分基于一阶动力学模型和二阶动力学模型。它们可简化植物活性成分提取过程中所涉及的生物、化学、物理及其相互影响的复杂过程,模型构式可线性化处理而使得参数求解简单,有利于促使模型应用于包括食品、植物、中药有效成分提取及组合提取工艺,如罐组逆流提取等[30−32]。本研究表明:一阶动力学模型和二阶动力学模型均可以用来描述植物中机械搅拌辅助提取和水浴提取动力学。针对机械搅拌辅助提取,二阶动力学模型具有更好的拟合度(R2≥0.997),水浴提取既适用于一阶动力学模型(R2≥0.931)也适用于二阶动力学模型(R2≥0.923),但较一阶动力学模型拟合度差。一阶动力学模型不能很好地描述成分提取过程[31]。

-

较高的决定系数(R2≥0.923)显示温度是影响植物中活性成分提取的重要因素,提取速率常数随着温度升高而升高,在温度较高时可以获得较好的提取率。10-DABⅢ和紫杉醇的机械搅拌辅助提取率分别为84.40%和93.88%;水浴提取的提取率分别为71.62%和93.35%。

本研究结果表明:温度升高可以提高10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取速率,动力学参数由Arrhenius方程确定,且提取速率与温度关系符合Arrhenius方程。在后续研究中仍需进一步考察搅拌速率与提取速率间的定量关系。动力学模型拟合得到提取动力学常数与温度符合Arrhenius方程,间接表明模型拟合结果是合理的。

本研究结果表明:模型使用广,可为提高云南红豆杉中10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇的提取和后续罐组逆流联合机械搅拌辅助提取的动力学模型提供理论依据,为工业化生产提供参数依据。

-

机械搅拌辅助提取符合二阶动力学方程,水浴提取符合一阶动力学方程。动力学分析结果表明:10-DAB Ⅲ和紫杉醇在机械搅拌辅助提取和水浴提取中的提取速率均随温度升高而增大,且呈线性关系(R2>0.905 5)。热力学分析结果显示:机械搅拌辅助提取和水浴提取的平衡常数速率 (Ke)随着温度升高而增大呈线性关系(R2>0.921 6)。通过Van’t Hoff方程得到2种提取方法的焓变值为正值(ΔH>0),熵变值为正值(ΔS>0),吉布斯自由能为负值(ΔG<0),表明提取过程是吸热的、湍流的且2种提取过程是自发进行的。通过Fick第二定律得到2种提取方法的有效扩散系数(De)和传质系数(KT)随温度升高而增大,而Biot随温度升高呈下降趋势且远大于100,表明2种提取方法均为内扩散。

Kinetics and thermodynamics study on the extraction process of 10-DAB Ⅲ and taxol from the branches and leaves of Taxus yunnanensis

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250193

- Received Date: 2025-03-12

- Accepted Date: 2025-10-20

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-10-15

- Available Online: 2026-01-27

- Publish Date: 2026-02-20

-

Key words:

- 10-deacetylbaccatin Ⅲ /

- taxol /

- dynamics /

- thermodynamics /

- Taxus yunnanensis

Abstract:

| Citation: | BAI Huilian, ZHU Jingbo. Kinetics and thermodynamics study on the extraction process of 10-DAB Ⅲ and taxol from the branches and leaves of Taxus yunnanensis[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2026, 43(1): 105−115 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250193 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: