-

森林水源涵养功能是陆地生态系统维持水文平衡、调节气候及防治水土流失的核心服务功能之一[1]。森林通过林冠截留降雨、凋落物层拦蓄水分及土壤层渗透储水等过程,实现降水资源的时空再分配[2]。在全球气候变化背景下,极端降水事件频发与水土流失加剧[3]使得森林水源涵养能力成为生态脆弱区可持续发展的关键调控因子[4]。黄土高原是全球土壤侵蚀最严重的区域之一,土层疏松、植被覆盖率低、降水集中且年际变化大[5]。这些特征导致地表径流冲刷强烈,生态系统稳定性极低。在此背景下,人工林建设成为该区域生态恢复的核心策略,其中刺槐Robinia pseudoacacia因兼具良好的生态效益和经济效益,成为黄土高原引种最成功的水土保持树种之一,也是黄土高原地区造林面积最大的树种之一[6]。但随着刺槐林龄的增大,其林龄结构老化问题日益突出,部分林分进入退化阶段,生态功能显著下降[7]。

现有研究表明:林分水源涵养能力受林龄显著影响,呈现阶段性变化特征。幼龄林因冠层稀疏、凋落物积累不足,截留与持水能力较弱;中龄林冠层郁闭度与生物量达到峰值,凋落物输入量增加,土壤结构逐步改善,水源涵养功能进入最佳阶段;林分成熟后因自然稀疏化、养分竞争加剧及根系退化,可能导致水源涵养功能开始衰退[8−10]。杨家慧等[11]发现:黔中地区柳杉Cryptomeria fortunei林冠层生物量随生长过程呈“单峰型”趋势,冠层截流能力也与之相近,峰值发生在成熟林时期。侯贵荣等[12]指出:黄土区刺槐林凋落物持水量与林龄呈正相关,但未明确是否存在阈值。以往研究多注重林分垂直方向单一层次或固定林龄条件下林分水源涵养功能,对于刺槐人工林的水源涵养功能随林龄增长的动态变化规律尚未明晰。此外,传统水源涵养功能评价方法(如层次分析法)也常因主观赋权导致结果偏差[13−14]。

针对上述问题,本研究以刺槐人工林幼龄林、中龄林、近熟林、成熟林、过熟林为对象,通过野外调查与室内实验结合,系统测定林冠截留能力、凋落物持水特性、土壤物理性质和持水能力,并运用熵权-逼近理想解排序(TOPSIS)法综合评价不同生长阶段刺槐林的水源涵养功能,探明不同生长阶段刺槐人工林各层次水源涵养功能变化特征,揭示刺槐林水源涵养功能的林龄效应机制,为研究区植被恢复和刺槐林的经营管理提供科学依据,提高该区生态系统的稳定性。

-

研究区位于山西省临汾市吉县蔡家川小流域(36°14′27″~36°18′23″N,110°39′45″~110°47′45″E)。流域面积为34.23 km2,海拔为898~1 574 m。该区属于温带大陆性季风性气候,年平均降水量为575.9 mm,年际变化大,降水多集中在6—8月,多年平均蒸发量为1 723.9 mm;无霜期为172.0 d;年平均气温为9.0~10.0 ℃,最高气温为38.1 ℃,最低气温为−20.4 ℃。土壤主要为弱碱性褐土,黄土母质,土层深厚,质地均匀,易发生水土流失。研究区典型刺槐纯林林分密度为1 500株·hm−2,林下灌草层基本稳定。主要灌木植物有黄刺玫Rosa xanthina、胡枝子Lespedeza bicolor、茅莓Rubus parvifolius等;草本植物以黄花蒿Artemisia annua、虉草Phalaris arundinacea、披针薹草Carex lancifolia等为主。

-

从1974年开始,吉县林业局就多次在蔡家川流域实施人工造林,特别是1991—1995年,造林规模最大,达1 000 hm2,主要造林树种为刺槐和油松Pinus tabuliformis 。本研究于2024年6—8月,在试验区内选取林分密度相近,土壤、地形等立地条件基本一致的刺槐人工林地为研究对象,用生长锥法确定实际林龄分别为15、23、27、34、41 a,并参考《主要树种龄级与龄组划分》[15]将其划分为幼龄林、中龄林、近熟林、成熟林、过熟林。按照不同林龄各设置3个样地,样地大小为20 m×20 m,调查样地内所有刺槐的树高、胸径、冠幅、叶面积指数,并估测林分密度。在每块样地的上坡、中坡、下坡分别设置30 cm×30 cm的凋落物样方,根据凋落物的颜色、形态将其分为未分解层和分解层,调查各层厚度,并全部收集。在每块样地中选取3个土壤取样点,挖掘深度为100 cm的土壤剖面。采用环刀法分别在0~20、20~40、40~60、60~80、80~100 cm分层取样,用于测定土壤物理性质。样地基本信息见表1。

龄组 海拔/m 坡度/(°) 坡向 密度/(株·hm−2) 平均树高/m 平均胸径/cm 平均冠幅/m 叶面积指数 幼龄林 1 021 15 阳坡 1 650 7.82±1.58 8.95±1.92 2.19±0.25 0.40±0.02 1 032 17 阳坡 1 600 8.79±0.79 9.34±2.06 2.32±0.16 0.42±0.02 1 034 17 阳坡 1 600 7.40±1.26 8.81±1.86 1.91±0.26 0.38±0.02 中龄林 1 107 18 阳坡 1 700 8.95±1.64 11.38±2.58 3.64±0.33 0.74±0.16 1 109 18 阳坡 1 700 8.86±1.47 10.92±1.76 2.98±0.36 0.72±0.08 1 106 18 阳坡 1 600 9.16±1.93 11.72±2.69 3.69±0.28 0.82±0.12 近熟林 1 149 19 阳坡 1 725 9.62±1.09 12.88±1.81 3.05±0.78 0.66±0.08 1 148 19 阳坡 1 625 9.04±0.87 11.93±2.18 2.84±0.72 0.56±0.06 1 146 19 阳坡 1 650 8.74±1.04 10.98±1.37 2.96±0.63 0.58±0.10 成熟林 1 174 16 阳坡 1 300 9.25±1.24 12.90±4.20 2.59±0.66 0.36±0.04 1 173 17 阳坡 1 600 9.43±1.37 13.92±1.92 2.75±0.58 0.44±0.05 1 175 19 阳坡 1 600 9.06±1.15 12.36±3.42 2.40±0.87 0.34±0.04 过熟林 1 232 14 阳坡 1 550 10.05±1.85 13.34±3.58 2.57±0.72 0.29±0.02 1 228 16 阳坡 1 550 10.76±1.47 12.98±1.53 2.96±0.57 0.30±0.02 1 230 14 阳坡 1 600 9.65±1.29 13.88±3.09 2.48±0.86 0.26±0.01 说明:平均树高、平均胸径、平均冠幅和叶面积指数数据为平均值±标准差。 Table 1. Basic information of the plot

-

2024年6—8月共观测到降雨事件7次。在每个样地中选择树高、胸径接近平均树高、平均胸径,能够代表该林分树形的平均木3株,设置树干流装置,连接集水槽,监测树干流;在每株标准木下和林窗中放置3个雨量筒监测穿透雨,每个雨量筒间隔大于2 m;在林外空旷处放置3个雨量筒,监测林外降雨。基于水量平衡计算实际的林分冠层截留量(率)。计算公式如下:

式(1)~(4)中:Q为降雨量(mm);V为雨量筒内水量(L);S为雨量筒的桶口面积(m2);Q0为林外降雨量(mm);Qc为林冠层截留量(mm);Q1为树干流水量(mm);Q2为林内降雨量(mm);V1为水槽内水量(L);S1为平均木林冠投影面积(m2);Rc为林冠截留率(%);θ为林分郁闭度(%)。

-

将收集的凋落物分层放入档案袋称量作为鲜质量,再在烘箱中85 ℃连续烘干12 h至恒量,作为干质量。采用连续浸泡法测定凋落物持水能力。将凋落物移至尼龙网袋,扎紧口部,浸没在装水的盆中,分别在0.25、0.50、1.00、2.00、4.00、6.00、12.00、24.00 h将网袋取出沥水至不再滴水,称量,作为浸泡后的质量。凋落物最大持水量(率)、凋落物有效拦蓄量(率)计算公式为:

式(5)~(8)中:R0为凋落物自然含水率(%);M0为凋落物鲜质量(g);M1为凋落物烘干后质量(g); M2为凋落物浸泡24 h后质量(g);Wl为凋落物最大持水量(g);Rm为凋落物最大持水率(%);Wm为凋落物最大拦蓄量(t·hm−2);R0为凋落物自然持水率(%);M为凋落物蓄积量(t·hm−2);W为凋落物有效拦蓄量(t·hm−2)。

-

用烘干法测定土壤含水量,用环刀法测定土壤密度、土壤毛管孔隙度和土壤非毛管孔隙度等物理性质。土壤层蓄水能力计算方法为:

式(9)~ (11)中:Wc、Wn、Wt分别为土壤毛管持水量、非毛管持水量、饱和持水量(t·hm−2);Pc、Pn分别为土壤毛管孔隙度、非毛管孔隙度(%);H为土壤深度(m)。

-

本研究采用熵权-TOPSIS法评价不同龄组刺槐林水源涵养功能。通过熵权法为各指标分配相对权重,TOPSIS法构造多目标决策矩阵,按照每个指标与理想化目标的接近程度进行排序,从而计算每个龄组刺槐林水源涵养功能与理想最优解和最劣解的综合距离,比较不同龄组刺槐林地水源涵养功能之间的差异。具体步骤如下:①指标原始数据矩阵设为X={xij}m×n。数据标准化处理采用归一化法,Yij为原始数据经过标准化后的矩阵,依据经标准化处理的数据计算各个指标信息熵(ej),得出指标权重(ωj)。

式(13)~(14)中:i 为第i个龄组,i=1,2,3,…,n ;j 为第j个评价指标,j=1,2,3,…,m。②用欧氏距离计算各龄组林分水源涵养功能与正理想解$ {(D}_{i}^{+} $)和负理想解$ {(D}_{i}^{-}) $的距离,并加入权重。

③计算各龄组林分水源涵养功能与正理想解的贴近度(Ci),即综合评价指数:

-

采用Excel 2019和SPSS 23.0进行数据统计分析,采用Origin 2018软件作图。采用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)和Duncan 法进行差异显著性检验。

-

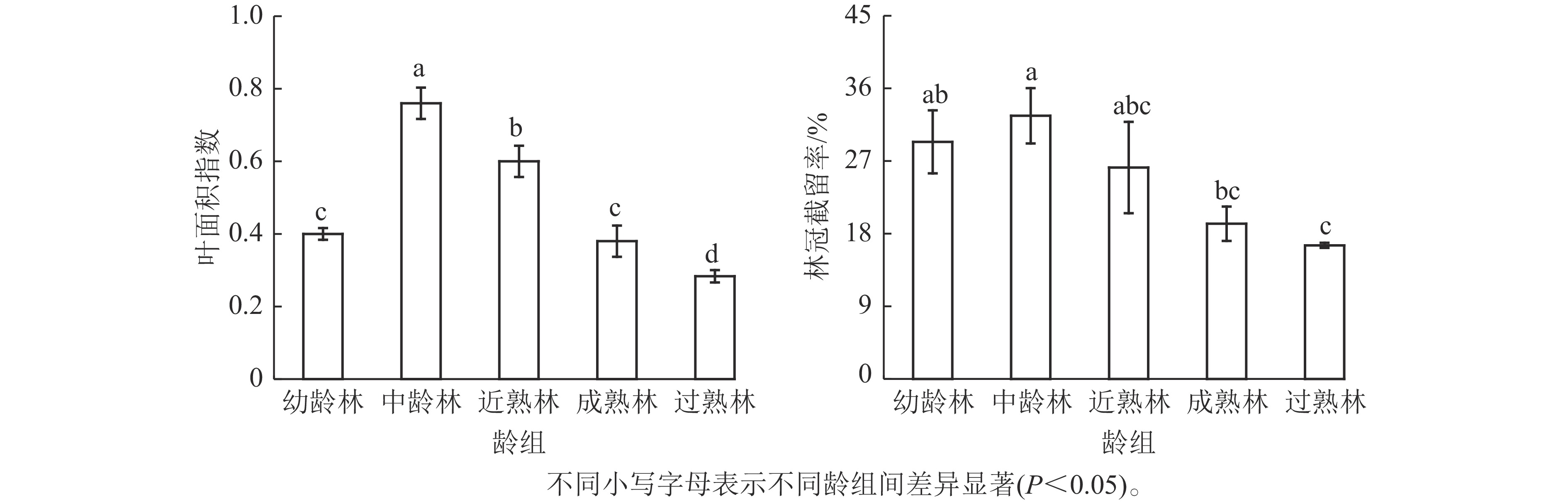

由图1可见:各林地刺槐林的叶面积指数随龄组的攀升呈先上升后下降的趋势,在中龄林时期达到最大,为0.76,过熟林最低,为0.28。除幼龄林与成熟林外,各林组的叶面积指数间存在显著差异(P<0.05)。各刺槐林林冠截流率随龄组攀升呈先增加后减小的趋势。中龄林林冠截留率最大,且显著高于成熟和过熟林(P<0.05),达33.44%。过熟林林冠截留率最低,仅为16.56%。

-

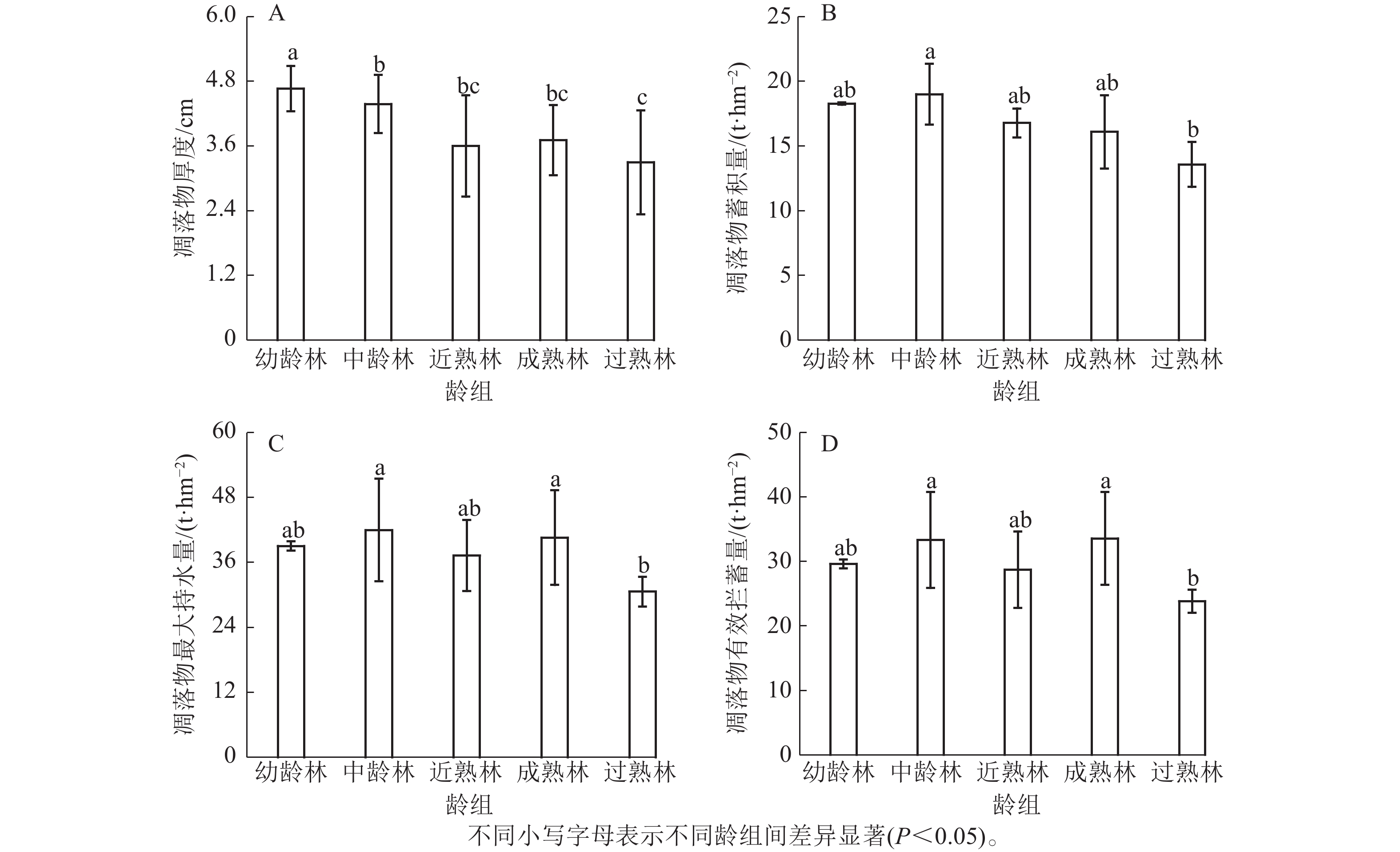

各龄组刺槐人工林凋落物厚度及蓄积量见图2A和图2B。凋落物厚度总体呈逐阶段降低趋势且均超过3 cm,最大为幼龄林(4.66 cm),显著高于近熟林、成熟林、过熟林(P<0.05)。在过熟林时凋落物厚度降至最低(3.30 cm),显著低于幼龄林和中龄林(P<0.05),其余林分凋落物厚度之间无显著差异。各龄组刺槐林凋落物蓄积量随龄组的攀升呈先上升后下降趋势,为13.58~19.01 t·hm−2,中龄林凋落物蓄积量最高,显著高于过熟林(P<0.05),过熟林凋落物蓄积量最低,其余各龄组刺槐林凋落物蓄积量之间无显著差异。

不同龄组刺槐林凋落物最大持水量为30.63~42.00 t·hm−2(图2C),最高为中龄林,成熟林与之相近,为40.59 t·hm−2,最低为过熟林,显著低于中龄林和成熟林(P<0.05)。由图2D可知:不同龄组刺槐林凋落物有效拦蓄量随龄组变化趋势与最大持水量相似,为24.41~33.57 t·hm−2,最高为成熟林,最低为过熟林。中龄林和成熟林有效拦蓄量显著高于过熟林(P<0.05),过熟林显著低于其余龄组(P<0.05)。

-

由表2可知:土壤容重随着龄组的攀升总体呈逐渐增大的趋势,最小为幼龄林(1.14 g·cm−3),显著低于其余生长阶段(P<0.05),最大为过熟林(1.33 g·cm−3)。土壤毛管孔隙度随着龄组的攀升呈先增大后减小的趋势,最大为中龄林(45.68%),过熟林(40.91%)显著低于其他龄组(P<0.05)。土壤非毛管孔隙随着龄组攀升总体呈先减小后增大的趋势,最大为幼龄林时期(5.52%),最低为中龄林时期(3.22%)。土壤总孔隙度总体呈逐阶段减小趋势,幼龄林阶段最大(49.23%),过熟林时期(45.31%)显著低于其余生长阶段(P<0.05)。

龄组 不同土层土壤容重/((g·cm−3) 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 1.06±0.02 1.18±0.03 1.16±0.03 1.15±0.04 1.15±0.02 1.14±0.02 b 中龄林 1.18±0.07 1.25±0.01 1.32±0.03 1.31±0.02 1.29±0.01 1.27±0.02 a 近熟林 1.13±0.08 1.24±0.02 1.25±0.02 1.29±0.02 1.26±0.01 1.23±0.02 ab 成熟林 1.23±0.03 1.33±0.06 1.27±0.03 1.23±0.04 1.23±0.02 1.26±0.02 a 过熟林 1.07±0.02 1.39±0.03 1.43±0.04 1.40±0.02 1.39±0.03 1.33±0.06 a 龄组 不同土层土壤毛管孔隙度/% 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 39.99±1.39 43.14±0.25 44.91±0.48 44.96±0.41 45.60±0.28 43.72±0.91 a 中龄林 46.22±0.63 44.61±0.49 44.32±0.92 47.28±1.39 45.99±0.07 45.68±0.49 a 近熟林 43.54±1.62 44.50±0.79 45.01±0.71 45.20±0.50 48.03±2.37 45.25±0.67 a 成熟林 43.75±1.53 42.24±1.39 44.46±0.04 44.50±0.67 44.39±0.87 43.87±0.38 a 过熟林 41.45±1.45 38.76±1.16 39.00±1.54 42.18±0.71 43.17±0.30 40.91±0.78 b 龄组 不同土层土壤非毛管孔隙度/% 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 9.62±1.04 4.37±0.20 4.27±0.14 5.17±0.82 4.14±0.12 5.52±0.93 a 中龄林 5.51±1.57 3.04±0.07 2.71±0.14 2.45±0.38 2.39±0.30 3.22±0.52 a 近熟林 6.43±1.11 3.25±0.70 3.15±0.40 2.45±0.40 2.29±0.44 3.51±0.67 a 成熟林 6.72±0.47 5.36±0.84 4.59±0.96 4.61±0.84 4.68±0.40 5.19±0.36 a 过熟林 11.98±1.56 2.80±0.46 2.42±0.39 2.44±0.22 2.36±0.28 4.40±1.70 a 龄组 不同土层土壤总孔隙度/% 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 49.61±1.90 47.51±0.37 49.17±0.57 50.13±0.70 49.74±0.25 49.23±0.41 a 中龄林 51.73±1.08 47.66±0.55 47.02±1.06 49.72±1.25 48.37±0.32 48.90±0.75 a 近熟林 49.97±1.71 47.74±0.75 48.16±0.60 47.65±0.85 50.31±2.10 48.77±0.51 a 成熟林 50.47±1.07 47.60±2.23 49.05±1.03 49.11±1.03 49.08±1.26 49.06±0.41 a 过熟林 53.43±0.21 41.56±0.71 41.42±1.90 44.62±0.57 45.53±0.35 45.31±1.96 b 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。均值后不同小写字母表示不同龄组间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 2. Physical properties of soil in woodland of different forest age group

土壤层水源涵养能力与土壤容重、孔隙度密切相关。由表2和表3可知:土壤持水量与土壤孔隙度随龄组增加的变化趋势一致,毛管持水量在中龄林最大,为913.65 t·hm−2,在过熟林最小,为818.23 t·hm−2,显著低于其余龄组(P<0.05)。幼龄林饱和持水量最大,为984.69 t·hm−2,过熟林饱和持水量显著低于其余生长阶段(P<0.05),为906.25 t·hm−2;非毛管持水量占总持水能力的比例为6.58%~11.21%,占比最小为中龄林,最大为幼龄林。

龄组 不同土层土壤毛管持水量/(t·hm−2) 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 799.73±33.96 862.83±6.06 898.11±11.77 899.12±10.11 911.99±6.89 874.35±18.22 a 中龄林 924.35±15.48 892.27±11.89 886.37±22.51 945.58±34.10 919.70±1.75 913.65±9.74 a 近熟林 870.80±39.57 889.95±19.40 900.18±17.50 903.98±12.13 960.52±58.02 905.08±13.42 a 成熟林 875.07±37.53 844.75±34.09 889.20±9.74 889.95±16.44 887.88±21.34 877.37±7.69 a 过熟林 829.05±35.42 775.12±28.33 779.95±37.64 843.62±17.31 863.39±7.23 818.23±15.65 b 龄组 不同土层土壤非毛管水持水量/(t·hm−2) 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 192.49±25.45 87.46±4.95 85.38±3.49 103.47±20.12 82.87±3.04 110.33±18.65 a 中龄林 110.25±38.35 60.90±1.66 54.12±3.52 48.91±9.26 47.72±7.31 64.38±10.47 a 近熟林 128.52±27.21 64.29±17.10 62.97±9.88 48.97±9.87 45.77±10.79 70.23±13.46 a 成熟林 134.36±11.45 107.30±20.63 91.85±23.41 92.29±20.65 93.67±9.87 103.89±7.28 a 过熟林 239.64±38.24 56.07±11.24 48.47±9.52 48.78±5.45 47.15±6.82 88.02±33.93 a 龄组 不同土层土壤饱和持水量/(t·hm−2) 0~20 20~40 40~60 60~80 80~100 cm 0~100 cm均值 幼龄林 992.22±46.43 950.28±8.94 983.50±13.95 1 002.58±17.24 994.86±6.20 984.69±8.16 a 中龄林 1 034.60±26.35 953.17±13.52 940.49±26.03 994.48±30.72 967.42±7.84 978.03±14.98 a 近熟林 999.32±41.86 954.87±18.42 963.15±14.76 952.92±20.92 1 006.29±51.46 975.31±10.20 a 成熟林 1 009.43±26.11 952.04±54.57 981.05±25.32 982.24±25.13 981.55±30.95 981.26±8.12 a 过熟林 1 068.69±5.17 831.18±17.27 828.42±46.56 892.40±13.93 910.54±8.48 906.25±39.14 b 说明:数据为平均值±标准差。均值后不同小写字母表示不同龄组间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 3. Soil water retention in woodlands of different age group

-

根据科学性、层次性和独立性的原则,选取林冠截流率、凋落物最大持水量、凋落物有效拦蓄量、土壤孔隙度、土壤持水量等作为评价指标,使用熵权-TOPSIS法计算各指标权重,评价水源涵养功能优劣,计算结果如表4所示。各指标权重为0.064 8~0.121 4,其中权重较大的指标有叶面积指数、非毛管孔隙、林冠截留率,分别为0.121 4、0.113 5、0.104 4。各层次权重从大到小依次为土壤层(0.481 1)、林冠层(0.295 6)、凋落物层(0.223 3)。由此可知,在刺槐人工林中,土壤层承担了主要的水源涵养功能。

一级指标 权重 二级指标 权重 一级指标 权重 二级指标 权重 林冠层 0.295 6 密度/(株·hm−2) 0.069 8 土壤层 0.481 1 土壤容重/(g·cm−3) 0.093 8 叶面积指数 0.121 4 毛管孔隙度/% 0.072 1 林冠截留率/% 0.104 4 非毛管孔隙度/% 0.113 5 总孔隙度/% 0.064 8 凋落物层 0.223 3 凋落物蓄积量/(t·hm−2) 0.077 0 毛管持水量/(t·hm−2) 0.072 1 凋落物最大持水量/(t·hm−2) 0.069 8 饱和持水量/(t·hm−2) 0.064 8 凋落物有效拦蓄量/(t·hm−2) 0.076 5 Table 4. The weight of each function of water conservation

通过TOPSIS法对各林分水源涵养能力进行综合评价,综合评价指数从大到小依次为中龄林、近熟林、幼龄林、成熟林、过熟林,分别为0.812 9、 0.618 8、0.612 9、 0.448 7、0.202 0。由幼龄林至过熟林阶段的各刺槐林地水源涵养能力呈先上升后下降的趋势,在中龄林阶段水源涵养功能达到峰值(表5)。

龄组 综合评价指数 排名 幼龄林 0.612 9 3 中龄林 0.812 9 1 近熟林 0.618 8 2 成熟林 0.448 7 4 过熟林 0.202 0 5 Table 5. Comprehensive evaluation value of water conservation function at different forest age group

-

森林的水源涵养功能是森林生态系统的重要生态功能之一[16],通过林冠层、凋落物层、土壤层拦截降水、减少地表径流、改善土壤物理性质,起到降雨再分配,调水蓄水的作用。本研究通过熵权法计算了水源涵养能力各指标权重,并使用TOPSIS法对不同龄组刺槐林水源涵养功能进行综合评价。

森林的水源涵养功能首先体现在林冠层对降水的截流及重新分配,直接对降雨的动能起削减作用,防止雨滴直接击溅地表,以缓解雨滴对土壤的溅蚀[17]。林冠层截留降雨作用的大小和降雨特征、林分类型以及树种特性等因素相关,冠层结构直接影响林冠层截流能力。本研究中各龄组刺槐林的林冠截流率为16.55%~32.60%,随龄组的攀升呈先增大后减小的趋势。张日施等[18]研究也表明:在桂西北地区秃杉Taiwania cryptomerioides林冠层截流能力随林龄的增大呈先增大后减小的趋势。这可能是由于刺槐林在幼龄林时期快速生长,林冠逐渐郁闭,在中龄林时达到峰值。此时资源竞争初现,林分产生自疏现象,导致林冠截留能力随龄组攀升而先上升后下降。幼龄林叶片面积大、蜡质层薄,有更强的亲水性,因此其单叶截留量要高于近熟林[19−20],但受制于林分郁闭程度,幼龄林的林冠截留量小于中龄林。

凋落物层是森林水源涵养的第2层次,通过地表覆盖减轻降雨侵蚀、延长水分入渗时间,并改善土壤结构与养分循环[21−22]。凋落物层的水源涵养功能由蓄积量、最大持水量和有效拦蓄量决定。研究表明:林分郁闭度与凋落物分解速率呈负相关,高郁闭度林分通过降低光照、穿透雨和温度抑制凋落物破碎淋溶,同时高郁闭度为林分带来更多的凋落物输入,从而使林下凋落物堆积更为紧密[23],因此各龄组林下凋落物蓄积量变化趋势与叶面积指数相似,均随刺槐龄组攀升先增大后减小。凋落物的蓄积量、分解程度决定了凋落物的持水能力。李良等[24]、侯贵荣等[12]认为:凋落物半分解层持水和拦蓄能力强于未分解层。本研究中最大持水量和有效拦蓄量在中龄林和成熟林中较大而近熟林较低,这可能是因为近熟林较成熟林郁闭度较高,导致凋落物分解程度低,因此半分解层凋落物占比小。同时,李江文等[25]研究表明:林下植被的覆盖度会随林分郁闭程度的增加而减小,故而成熟林林下植被覆盖度较大,有更多的凋落物输入,从而出现近熟林分水源涵养能力低于中龄林和成熟林的现象。可见林分郁闭度也会间接影响凋落物层的水源涵养功能。

土壤是森林储藏水分最主要的场所,其容重、孔隙度能反映土壤孔隙状况、松紧程度,评价土壤空气和水分的通透情况[26],直接影响土壤层水源涵养能力。土壤毛管孔隙与非毛管孔隙分别主导土壤的储水和透水性能,两者持水量总和直接表征土壤水源涵养潜力上限[27−29]。从研究区不同生长阶段刺槐林地的土壤性状来看,幼龄林土壤非毛管孔隙度与总孔隙度最大且容重最小,表现出最优透水性能;中龄林土壤毛管孔隙度达到峰值,储水能力显著增强;过熟林土壤孔隙结构退化,持水能力降至最低。这可能是因为凋落物分解速率受林分郁闭度抑制,但与土壤有机质积累呈正相关关系[30]。受叶面积指数随龄组攀升先增后减的规律影响,幼龄林凋落物分解更为彻底,其土壤有机质质量分数高于中龄林。这一过程进一步促进土壤团聚体形成并诱导大孔径孔隙发育[31],因此不同龄组林分的郁闭程度差异也间接影响了不同生长阶段刺槐林土壤层水源涵养功能。同时刺槐根系集中在40~80 cm土层中[32],有机质的“表聚”现象和深层根系的穿插作用,使得土壤孔隙呈现出先减小后增大的趋势。

熵权-TOPSIS法可以完全剔除主观因素的影响,客观地判断各评价因素的相对重要性,并且解决因各层次内涵不同,不能相加的弊端[33]。同时,排序结果直观且符合逻辑,能够有效区分不同生长阶段林分土壤的水源涵养功能的相对优劣。本研究采用熵权-TOPSIS法对5个龄组刺槐林土壤进行水源涵养功能评价并排序,结果表明:各龄组刺槐林的水源涵养能力随龄组的攀升先增大后减小,可见刺槐林水源涵养功能有一定阈值,到达一定林龄,水源涵养功能将逐渐减弱。这与张甜等[26]、WANG等[34]的研究结果一致。水源涵养能力最佳的为中龄林。ZHAO等[10]在晋西黄土区不同林龄刺槐林生态功能的研究中也表明:刺槐人工林在成熟前主要提供水源涵养功能。这可能是由于叶面积指数、凋落物蓄积量、土壤毛管孔隙度等均随龄组的攀升而先增大后减小,在中林龄阶段达到峰值,进而影响水源涵养功能。

-

在刺槐林林冠层,各龄组叶面积指数、冠层截留率变化趋势一致,均表现出随龄组的攀升而先上升后下降的趋势,中龄林水源涵养能力高于其余龄组林分。在凋落物层,凋落物蓄积量表现为随龄组攀升先增大后减小,中龄林高于其余林分;凋落物最大持水量和最大拦蓄量在中龄林和成熟林中有更好的表现;同时半分解层的蓄积量、最大持水量、有效拦蓄量均大于未分解层。在土壤层,土壤容重、土壤非毛管孔隙度、土壤总孔隙度及土壤各孔隙对应的持水量表现为幼龄林高于其余林分,毛管孔隙度和毛管持水量均表现为中龄林高于其余林分。在0~100 cm土层中,土壤孔隙度和持水量基本随土层深度增加而先减小后增大的趋势,土壤容重则与之相反。通过熵权法分析认为,影响刺槐林地水源涵养功能的主要因素为叶面积指数、非毛管孔隙度、林冠截留能力, TOPSIS法评价各龄组刺槐人工林水源涵养能力从高到低依次中龄林、近熟林、幼龄林、成熟林、过熟林,说明在相似的立地条件下,中林龄刺槐林地有更好的水源涵养功能。建议结合研究区现有低效林改造及功能提升工程,对现有低效和衰退林分进行合理采伐与补植,以更好地提升刺槐人工林水源涵养功能。

Evaluation of water conservation function of Robinia pseudoacacia plantation at different growth stages

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250275

- Received Date: 2025-04-29

- Accepted Date: 2025-08-14

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-08-11

- Available Online: 2025-09-11

-

Key words:

- Robinia pseudoacacia plantations /

- age group /

- water conservation function /

- entropy weight-TOPSIS method /

- loess regions in western Shanxi

Abstract:

| Citation: | ZENG Xing, BI Huaxing, GUAN Ning, et al. Evaluation of water conservation function of Robinia pseudoacacia plantation at different growth stages[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2025, 42(X): 1−11 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250275 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: