-

随着天然林保护工程的开展,天然林被禁伐,人工林成了获取木材的主要手段。中国是全世界人工林面积最大的国家,人工林已经成为森林资源的重要组成部分,对社会发展和生态建设发挥着越来越重要的作用,但由于人工纯林树种单一,对物质吸收利用的选择性和对环境效应的特殊性[1],在其长期经营过程中,土壤性质往往呈现极端化发展的趋势。这种趋势进一步恶化,导致群落生物多样性降低,生态功能下降,并改变了群落的物种组成及结构特征等问题。凋落物是生态系统中养分进入土壤的重要来源,为土壤动物提供重要的栖息和食物来源[2]。土壤动物作为生态系统中养分循环的重要参与者[3],通过破碎、摄食凋落物促进生态系统物质循环和能量流动,通过间接刺激微生物的生长达到促进凋落物能量流动和生态系统物质循环[4-10]。跳虫作为世界上种类最丰富的小型节肢动物之一,与线虫、螨类共同构成土壤中三大主要土壤动物类群[11]。它们通过取食植物组织、土壤中的腐殖质、动植物残骸、真菌或细菌等,直接或间接地参与自然界物质循环[12],维护土壤理化特性[11]。本研究以中亚热带内陆地区都江堰灵岩山4种林型[柳杉Cryptomeria fortunei人工林、楠木Phoebe zhennan人工林、水杉Metasequoia glyptosyroboides人工林、阔叶次生林(以下简称次生林)]为研究对象,调查研究这4种林型凋落物层跳虫群落动态特征,为人工林的合理经营及生物多样性的保护提供科学依据。

-

试验地位于成都平原与四川盆周西缘山地接合部的都江堰灵岩山(30°44′54″~31°22′09″N,103°25′42″~103°25′47″E),属亚热带气候,海拔为852~1 075 m,为浅切割低山地貌类型。年平均气温为15.2 ℃,极端最高、最低气度分别为38.0 ℃和-10.0 ℃,年平均相对湿度81%,年平均降水量1 243.0 mm,年平均日照时数1 024.2 h,无霜期269.0 d。样地土壤为沙岩上发育的黄壤,质地为重壤质,pH 6.5~6.8。由于多雨,在淀积层与母质层之间有明显的潜育现象,土壤肥力中等,保肥保水性好。

楠木林栽植于20世纪50年代,是在洋槐Robinia pseudoacacia林采伐迹地上人工更新形成的,其初植密度为3 333株·hm-2,自然稀疏后,曾进行过不定期的轻度择伐,目前活立木保留833株·hm-2[13]。柳杉林和水杉林分别种植于20世纪70年代和80年代,是在灌丛地上进行更新形成的。各样地主要植物有三枝九叶草Epimedium sagittatum,扁竹根Iris japonica,短柄枹栎Quercus serrata,钝叶铃木Eurya obtusifolia,悬钩子Rubus spp.,胡枝子Lespedeza bicolor等[14]。样地基本情况见表 1。

表 1 人工林样地基本信息

Table 1. Basic condition of 3 artificial stands

林分类型 海拔/m 坡度/(°) 坡向/(°) 胸径/cm 树高/m 林龄/a 林分郁闭度/% 密度/(株·hm-2) 柳杉林 876 15 SE45 21.67 18.7 39 80 800 水杉林 720 8 SE15 33.20 22.6 30 75 900 楠木林 720 10 SE15 25.60 20.5 60 82 833 次生林 870 11 SE25 28.86 18.4 70 说明:以上数据测定于2013年7月。 -

于2013年5月、7月、9月和11月中旬分别在各林分中设置面积为20 m × 20 m样地。各样地内按照“品”字形进行布点取样,在每个面积为30 cm × 30 cm(0.09 m2)的样方内采集凋落物样。将所取样品带回室内用改进的干漏斗(Tullgren法)连续分离48 h[15],在室内利用解剖镜和生物显微镜计数和分类。跳虫的鉴定主要参照《中国土壤动物检索图鉴》[16]及《弹尾纲4目分类系统》[17]进行。一般鉴定到科,同时统计个体数量。

-

采用多样性指数、均匀性指数、优势度指数、丰富度指数及相似性指数等对各林型凋落物层跳虫群落多样性进行分析。Shannon-Wiener多样性指数$H' = - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^s {{P_i}} \ln {P_i}$,Pielou均匀性指数$E = H'/\ln S$,Simpson优势度指数$C = - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^s {{{\left( {{n_i}/N} \right)}^2}} $,Margalef丰富度指数:M=(S-1)/lnN,Sorensen相似性系数Cs=2j/(a+b)。其中:ni为该区内第i个类群的个体数量;N为该样区内所有类群的个体数量;Pi=ni/N;S为样区内类群个数。j为2个群落共有的类群数;a和b分别为群落A和B的类群数。计算值在0.75~1.00为极相似,在0.50~0.74为中等相似,在0.25~0.49为中等不相似,在0.00~0.24为极不相似。

-

各类群数量优势度的划分:类群密度占总密度10%以上者为优势类群,1%~10%为常见类群,1%以下为稀有类群。

-

数据的处理和分析采用SPSS 17.0和Excel 2010进行。

-

本试验各林型共捕获跳虫1 496头,隶属于11科。不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落组成见表 2,以长角科Entomobryidae,等节科Isotomidae和圆科Sminthuridae为优势类群,其个体数量分别占本次捕获量的40.04%, 30.35%和14.44%;常见类群包括棘科等共4类,其个体数量所占比例为13.37%;其余4类为稀有类群,其个体数量所占比例为1.80%。其中,水杉林共捕获跳虫290头,共29个科,以等节科、长角科和圆科为优势类群,其个体数分别占捕获量的51.72%,17.24%和14.48%;以球角科Hypogastruridae等共4个类群为常见类群,其个体数量所占比例为15.52%;其余2类为稀有类群,所占比例为1.03%。柳杉林共捕获跳虫768头,共11个科,以等节科、长角科和圆科为优势类群,其个体数分别占捕获量的28.65%,43.10%和13.41%;以棘科等4个类群为常见类群,其个体数量所占比例为12.76%;其余4类为稀有类群,所占比例为2.08%。楠木林共捕获跳虫352头,共7个科,以等节科、长角科和圆科为优势类群,其个体数分别占捕获量的19.89%,50.85%和15.06%;以棘科等3个类群为常见类群,其个体数量所占比例为13.92%;稀有类群为鳞科,所占比例为0.28%。次生林共捕获跳虫86头,共6个科,以等节科、长角科和圆科为优势类群,其个体数分别占捕获量的16.28%,45.35%和20.93%;以鳞科、棘科和驼科为常见类群,常见类群个体数量所占比例为17.44%。

表 2 不同林分跳虫群落组成

Table 2. Composition of collembolan communities in different forest types

科名 水杉林 柳杉林 楠木林 次生林 合计 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 等节虫兆科Isotomidae 150 51.72 220 28.65 70 19.89 14 16.28 454 30.35 短角虫兆科Veelidae 7 2.41 6 0.78 13 0.87 棘虫兆科Onychiuridae 6 2.07 47 6.12 35 9.94 6 6.98 94 6.28 鳞虫兆科Tomoceridae 13 1.69 1 0.28 8 9.30 22 1.47 球角虫兆科Hypogastruridae 27 9.31 25 3.26 6 1.70 58 3.88 虫兆虫科Poduridae 5 1.72 13 1.69 8 2.27 26 1.74 驼虫兆科Cyphoderidae 2 0.69 2 0.26 1 1.16 5 0.33 疣虫兆科Veanuridae 1 0.34 6 0.78 7 0.47 圆虫兆科Sminthuridae 42 14.48 103 13.41 53 15.06 18 20.93 216 14.44 长角虫兆科Entomobryidae 50 17.24 331 43.10 179 50.85 39 45.35 599 40.04 长角长虫兆科Orchesellidae 2 0.26 2 0.13 个体数/头 290 768 352 86 1 496 类群数/个 9 11 7 6 11 差异性分析结果显示:柳杉林跳虫个体数显著高于其他3类林型(P < 0.05),同时,水杉林和楠木林跳虫个体数显著高于次生林(P < 0.05),跳虫类群数以柳杉林显著高于次生林(P < 0.05)。

-

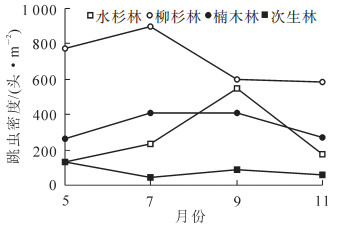

不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落月动态变化见图 1和图 2。可以看出:各林型凋落物层跳虫个体密度与类群数具有相似的动态变化趋势。其中,跳虫个体数均以柳杉林最高,次生林最低(图 1),跳虫类群数除5月外,均以次生林最低(图 2)。对各林型跳虫个体数月变化动态分析结果显示:水杉林土壤跳虫个体数大小排序为9月 > 7月 > 11月 > 5月,柳杉林土壤跳虫个体数大小排序为7月 > 5月 > 9月 > 11月,楠木林土壤跳虫个体数大小排序为9月 > 7月 > 11月 > 5月,次生林土壤跳虫个体数大小排序为5月 > 9月 > 11月 > 7月。

各类林型跳虫类群数月变化动态分析结果显示:5月类群数以柳杉林最高,为11类,楠木林和次生林次之,均为6类,水杉林最低,为5类;7月类群数排序为柳杉林(11) > 楠木林(10) > 水杉林(6) > 次生林(3);9月类群数以楠木林最高,为9类,水杉林和柳杉林次之,均为7类,次生林最低,为4类;11月类群数以柳杉林最高,为8类,水杉和楠木林次之,为6类,次生林最低,为4类。

-

为深入了解不同林型凋落物层跳虫群落多样性特征,选取Simpson优势度指数(C),Shannon-Wiener多样性指数(H'),Pielou均匀性指数(E)及丰富度指数(M)对各林型凋落物层跳虫多样性特征进行研究。综合4次采样数据分析,结果显示(表 3):优势度指数(C)以楠木林最高,水杉林、柳杉林次之,次生林最低;多样性指数(H')大小排序为柳杉林 > 水杉林 > 楠木林 > 次生林;均匀性指数(E)大小排序为次生林 > 楠木林 > 水杉林 > 柳杉林;丰富度指数(M)则以柳杉林 > 水杉林 > 次生林 > 楠木林。

表 3 不同林分跳虫群落多样性

Table 3. Diversities of collembolan communities in different forest types

林分类型 Simpson优势度指数(C) Shannon-Wiener多样性指数(H') Pielou均匀性指数(E) 丰富度指数(M) 水杉林 0.328 1.439 0.655 1.411 柳杉林 0.291 1.518 0.633 1.505 楠木林 0.332 1.352 0.695 1.023 次生林 0.290 1.440 0.804 1.122 为了解不同月份跳虫的动态特征,对不同时期凋落物层跳虫群落多样性动态变化进行研究。从图 3可以看出,随着时间的变化,水杉和次生林的多样性指数(H')具有相似的变化趋势,即先下降后上升,柳杉林则是呈现出先上升后下降的趋势;均匀性指数(E)和优势度指数(C)均以水杉林和次生林、柳杉林和楠木林具有相似的变化趋势;丰富度指数(M)除9月以外均以柳杉林最高。

-

综合各月数据进行相似性分析表明(表 4):水杉林和楠木林相似性系数最高(0.900),柳杉林与楠木林次之(0.778),次生林与水杉林最低(0.667),其中,次生林分别与水杉林、柳杉林间相似性系数计算值为0.50~0.74,为中等相似,其余林分间的相似性系数计算值均为0.75~1.00,为极相似。

表 4 不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落相似性

Table 4. Similarities between collembolan communities in different forest types

林分 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 1.000 次生林 0.667 1.000 柳杉林 0.900 0.706 1.000 楠木林 0.750 0.769 0.778 1.000 进一步对各月相似性进行分析显示(表 5):除柳杉林和楠木林相似性系数在7月达最高外,不同林分间相似性系数最高值均出现在9月,最小值分别出现在5月和7月。其中,柳杉林和楠木林相似性系数最高值在7月为0.923,相似性系数为0.750~1.000,为极相似;次生林和柳杉林在7月相似性系数最低值为0.286,相似性系数计算值为0.250~0.490,为中等不相似。

表 5 不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落相似性

Table 5. Similarities between collembolan communities in different forest types

林分 5月 7月 9月 11月 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 次生林 0.600 1.000 0.444 1.000 0.727 1.000 0.600 1.000 柳杉林 0.500 0.375 1.000 0.353 0.286 1.000 0.857 0.727 1.000 0.857 0.500 1.000 楠木林 0.545 0.364 0.588 1.000 0.923 0.400 0.667 1.000 0.750 0.615 0.875 1.000 0.833 0.500 0.714 1.000 -

在绝大多数生态系统中,跳虫是主要的优势类群之一,因此,跳虫个体密度及类群数多少对了解特定生态系统的状态及其发展具有重要意义。研究结果显示:各人工林跳虫密度及类群数均高于次生混交林,4类林型中柳杉人工林跳虫密度及类群数均最高,次生林密度及类群数均为最低,表明柳杉人工林较其他3类生态系统更适合跳虫的繁殖和栖息。同时,随着时间的推移,不同林型间凋落物层跳虫密度和类群数表现出一定的差异,这种变化体现了不同类群的跳虫在生物生态学习性上的差异及对环境的适应[18]。各林型下跳虫密度和类群数基本在7月或9月最高(次生林除外),这主要与该时期气温较高,加上降水丰富,有利地促进了凋落物的分解速度,加速了绝大多数跳虫的食物来源--微生物的繁殖[19]。适当的温度和水分是跳虫生存的前提,丰富的凋落物及适当的环境条件有利于跳虫种群的增加。

林下凋落物作为生态系统的重要组成部分,在提高森林生产力,促进能量转化、物质循环和水量平衡等方面具有重要的意义[13]。本实验所研究的4种林型中,柳杉和楠木均为常绿乔木,水杉为落叶乔木,次生混交林则落叶和常绿兼有。落叶和常绿树种对凋落物的蓄积和季节动态具有重要的影响,其中,凋落物量的保存会吸引更多的跳虫集聚于土壤表层[18],是提高跳虫个体密度及多样性的关键因素。然而,本研究中,各林分凋落物蓄积量以楠木林最高(3.3 t·hm-2),柳杉林最低(0.61 t·hm-2)[13],各林型凋落物层跳虫密度和类群数并不与凋落物蓄积量一致,说明凋落物蓄积量及分解阶段对跳虫密度及类群数没有决定性的影响。跳虫的集聚型反映了其对变化着的生境和食物源的适应性,在凋落物分解的不同阶段,适应生境和食物源的跳虫种类组成不同,因此,不同人工林凋落物层跳虫群落结构受凋落物性质的影响而出现一定的差异,不同植被类型是影响跳虫群落结构和多样性的主要因素。同时,常绿人工林没有明显的落叶期,其林下跳虫群落主要受季节的影响较大。11月为水杉集中落叶期,是其凋落物蓄积量最高的时段,然而跳虫个体及类群的季节分布特征并没有因此而出现较大波动。这主要与凋落物的分解需要一定的时间和适合的气温和降水有关。

多样性指数作为生态环境评价的重要指标,可以反映群落组成的复杂程度,其高低能反映群落的稳定性,常用来评价群落生态的组织水平,开展相关研究对于整个生态系统的研究有重要的意义。本研究中,不同林型间以及不同时间,凋落物层跳虫群落多样性指数均表现出一定的变化,拥有较高个体数和类群数的林型在跳虫多样性指数比较中具有较大优势,多样性指数值很好地综合反映了各生境跳虫种群组成的差异。同时,本研究对跳虫仅鉴定到科水平,而分类水平对多样性指数的值影响较大,一般认为土壤动物大类群水平的变化远远不如属、种水平上的变化敏感[20],因此从研究的灵敏度考虑,在今后的研究中应该增强对跳虫更细的分类,但同时更低的分类单元对鉴定技术和设备有较大的要求。

一般而言,天然林较人工林纯林生态系统具有更高的生物多样性。研究显示,人工林经过长期演替后,其林下跳虫的密度及类群数能达到甚至超过形成时间较短的次生混交林,部分人工林甚至较次生混交林凋落物的跳虫多样性及丰富度具有更好的表现。这可能与次生林形成时间较短,生态系统正处于不断演替阶段,其生态系统较长期演替后的人工林脆弱有关。同时,相关研究结果显示,跳虫在凋落物分解的中后期起主要分解功能[20],研究各林型下凋落物的组成与跳虫群落的关系,有利于了解跳虫在各林型凋落物分解过程中的贡献,为经营人工林生态系统提供科学依据。

Collembola community characteristics for litter layers in typical plantations of mountainous western Sichuan

-

摘要: 为了解典型人工林下凋落物层跳虫群落结构特征,于2013年5月、7月、9月和11月中旬对四川盆周西缘山地的楠木Phoebe zhennan人工林、水杉Metasequoia glyptosyroboides人工林、柳杉Cryptomeria fortunei人工林和次生林4种林型下凋落物层跳虫群落结构进行调查。结果表明:试验共捕获跳虫1 496头,隶属于11科。各林型凋落物层跳虫个体密度与类群数具有相似的变化趋势,其中,跳虫个体数和类群数均以柳杉林最高,分别为768头和11科,以次生林最低,分别为86头和6科。各林型均以长角(虫兆)科Entomobryidae,等节(虫兆)科Isotomidae和圆(虫兆)科Sminthuridae为优势类群,其个体数所占比例均在82%以上。研究显示,各林型凋落物层跳虫密度和类群数并不与凋落物蓄积量一致,说明凋落物蓄积量对跳虫密度及类群数没有决定性的影响;相似性分析显示,除柳杉和楠木相似性系数在7月达最高外,不同林分间相似性系数最高值均出现在9月,最小值分别出现在5月和7月。Abstract: To determine the characteristics of the Collembola community in the litter layer of typical artificial plantations, Cryptomeria fortunei, Phoebe zhennan, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, and a secondary-forest were selected and studied in May, July, September, and November of 2013. Analysis included a similarity index. Results comprised a total collection of 1 496 samples of soil fauna belonging to 11 families. Of these, 290 belonging to 9 families were found in M. glyptostroboides stands, 352 belonging to 7 families were collected in Phoebe zhennan plots, 768 belonging to 11 families were collected in C. fortunei stands, and 86 belonging to 6 families were collected in the secondary-forest. The highest number of Collembola for each month was found in C. fortunei, and the lowest number (except for May) was found in the secondary-forest. In each forest type, Isotomidae, Sminthuridae, and Entomobryidae were the dominant families. No direct relation between the individual number and families of Collembola and litter accumulation were found. Also, the similarity index studies showed that the highest value was found in September (excepting July), and the smallest values were found in May and July.

-

Key words:

- soil zoology /

- typical plantations /

- litter layer /

- Collembola /

- community characteristics

-

表 1 人工林样地基本信息

Table 1. Basic condition of 3 artificial stands

林分类型 海拔/m 坡度/(°) 坡向/(°) 胸径/cm 树高/m 林龄/a 林分郁闭度/% 密度/(株·hm-2) 柳杉林 876 15 SE45 21.67 18.7 39 80 800 水杉林 720 8 SE15 33.20 22.6 30 75 900 楠木林 720 10 SE15 25.60 20.5 60 82 833 次生林 870 11 SE25 28.86 18.4 70 说明:以上数据测定于2013年7月。 表 2 不同林分跳虫群落组成

Table 2. Composition of collembolan communities in different forest types

科名 水杉林 柳杉林 楠木林 次生林 合计 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 个体数/头 多度/% 等节虫兆科Isotomidae 150 51.72 220 28.65 70 19.89 14 16.28 454 30.35 短角虫兆科Veelidae 7 2.41 6 0.78 13 0.87 棘虫兆科Onychiuridae 6 2.07 47 6.12 35 9.94 6 6.98 94 6.28 鳞虫兆科Tomoceridae 13 1.69 1 0.28 8 9.30 22 1.47 球角虫兆科Hypogastruridae 27 9.31 25 3.26 6 1.70 58 3.88 虫兆虫科Poduridae 5 1.72 13 1.69 8 2.27 26 1.74 驼虫兆科Cyphoderidae 2 0.69 2 0.26 1 1.16 5 0.33 疣虫兆科Veanuridae 1 0.34 6 0.78 7 0.47 圆虫兆科Sminthuridae 42 14.48 103 13.41 53 15.06 18 20.93 216 14.44 长角虫兆科Entomobryidae 50 17.24 331 43.10 179 50.85 39 45.35 599 40.04 长角长虫兆科Orchesellidae 2 0.26 2 0.13 个体数/头 290 768 352 86 1 496 类群数/个 9 11 7 6 11 表 3 不同林分跳虫群落多样性

Table 3. Diversities of collembolan communities in different forest types

林分类型 Simpson优势度指数(C) Shannon-Wiener多样性指数(H') Pielou均匀性指数(E) 丰富度指数(M) 水杉林 0.328 1.439 0.655 1.411 柳杉林 0.291 1.518 0.633 1.505 楠木林 0.332 1.352 0.695 1.023 次生林 0.290 1.440 0.804 1.122 表 4 不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落相似性

Table 4. Similarities between collembolan communities in different forest types

林分 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 1.000 次生林 0.667 1.000 柳杉林 0.900 0.706 1.000 楠木林 0.750 0.769 0.778 1.000 表 5 不同林分凋落物层跳虫群落相似性

Table 5. Similarities between collembolan communities in different forest types

林分 5月 7月 9月 11月 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 次生林 柳杉林 楠木林 水杉林 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 次生林 0.600 1.000 0.444 1.000 0.727 1.000 0.600 1.000 柳杉林 0.500 0.375 1.000 0.353 0.286 1.000 0.857 0.727 1.000 0.857 0.500 1.000 楠木林 0.545 0.364 0.588 1.000 0.923 0.400 0.667 1.000 0.750 0.615 0.875 1.000 0.833 0.500 0.714 1.000 -

[1] 米彩红, 刘增文, 李茜.黄土丘陵区3种典型人工阔叶纯林枯落物分解对土壤性质极化的影响[J].西北农林科技大学学报(自然科学版), 2012, 40(7):120-126. MI Caihong, LIU Zengwen, LI Qian. Effect of litter decomposition on soil properties polarization of three tyical artificial pure broadleaved forests in the Loess Hilly Area[J]. J Northwest A & F Univ Nat Sci Ed, 2012, 40(7):120-126. [2] 柯欣, 赵立军, 尹文英.青冈林土壤跳虫群落结构在落叶分解过程中的变化[J].生态学报, 2001, 21(6):982-987. KE Xin, ZHAO Lijun, YIN Wenying. Succession of collembolan community structure during decomposition of leaves in Cyclobalanopsis glauca forest[J]. Acta Ecol Sin, 2001, 21(6):982-987. [3] FRECKMAN D W, BLACKBURN T H, BRUSSAARD L, et al. Linking biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of soils and sediments[J]. Ambio, 1997, 26(8):556-562. [4] 杨万勤, 邓仁菊, 张健.森林凋落物分解及其对全球气候变化的响应[J].应用生态学报, 2008, 18(12):2889-2895. YANG Wanqin, DENG Renju, ZHANG Jian. Forest litter decomposition and its responses to global climate change[J]. Chin J Appl Ecol, 2008, 18(12):2889-2895. [5] WHALEN J K, BOTTOMLEY P J, MYROLD D D. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization from light-and heavy-fraction additions to soil[J]. Soil Biol Biochem, 2000, 32(32):1345-1352. [6] WISE D, SCHAEFER M. Decomposition of leaf litter in a mull beech forest:comparison between canopy and herbaceous species[J]. Pedobiologia, 1994, 38(3):269-288. [7] EKSCHMITT K, LIU M, VETTER S, et al. Strategies used by soil biota to overcome soil organic matter stability-why is dead organic matter left over in the soil?[J]. Geoderma, 2005, 128(1/2):167-176. [8] MARAUN M, SCHEU S. Changes in microbial biomass, respiration and nutrient status of beech (Fagus sylvatica) leaf litter processed by millipedes (Glomeris marginata)[J]. Oecologia, 1996, 107(1):131-140. [9] SEASTEDT T R. The role of microarthropods in decomposition and mineralization processes[J]. Ann Rev Entomol, 1984, 29(1):25-46. [10] 李艳红, 罗承德, 杨万勤, 等.桉-桤混合凋落物分解及其土壤动物群落动态[J].应用生态学报, 2011, 22(4):851-856. LI Yanhong, LUO Chengde, YANG Wanqin, et al. Decomposition of eucalyptus-alder mixed litters and dynamics of soil faunal community[J]. Chin J Appl Ecol, 2011, 22(4):851-856. [11] 陈建秀, 麻智春, 严海娟, 等.跳虫在土壤生态系统中的作用[J].生物多样性, 2007, 15(2):154-161. CHEN Jianxiu, MA Zhichun, YAN Haijuan, et al. Roles of springtails in soil ecosystem[J]. Biodivers Sci, 2007, 15(2):154-161. [12] SCHOLLE G, WOLTERS V, JOERGENSEN R. Effects of mesofauna exclusion on the microbial biomass in two moder profiles[J]. Biol Fert Soil, 1992, 12(4):253-260. [13] 肖玖金, 马海燕, 张晓庆, 等.四川盆周西缘山地典型人工林下苔藓和凋落物的持水特性[J].东北林业大学学报, 2014, 42(9):62-65. XIAO Jiujin, MA Haiyan, ZHANG Xiaoqing, et al. Water holding capacities of bryophyte and litter layer under typical artificial stands of western Sichuan Basin border[J]. J Northeast For Univ, 2014, 42(9):62-65. [14] 卢昌泰, 李云, 肖玖金, 等.四川盆周西缘山地3种人工林土壤动物群落特征[J].应用与环境生物学报, 2013, 19(4):618-622. LU Changtai, LI Yun, XIAO Jiujin, et al. Characteristics of soil fauna community of three plantations in the western Sichuan Basin Border of China[J]. Chin J Appl Environ Biol, 2013, 19(4):618-622. [15] 陈鹏, 田中真悟.长春净月潭地区土壤跳虫的生态分布[J].昆虫学报, 1990, 33(2):219-226. CHEN Peng, TANAKA S G. Primary investigation on soil collembola in Jingyuetan region of changchun[J]. Acta Entomol Sin, 1990, 33(2):219-226. [16] 尹文英.中国土壤动物检索图鉴[M].北京:科学出版社, 1998. [17] CHRISTIANSEN K. Checklist of the collembola of the world[EB/OL].[2015-01-13]http://www.collembola.org. [18] 靳亚丽, 由文辉, 易兰, 等.天童森林生态系统凋落物层跳虫群落的生态学研究[J].生态环境学报, 2011, 20(2):241-247. JIN Yali, YOU Wenhui, YI Lan, et al. Ecological distribution of collembola in the litter of Tiantong forest ecosystems, Zhejiang[J]. Ecol Environ Sci, 2011, 20(2):241-247. [19] 佟富春, 陈步峰, 谢正生, 等.广州白云山几种林分修复模式下凋落物跳虫群落的特征[J].东北林业大学学报, 2010, 38(4):94-97. TONG Fuchun, CHEN Bufeng, XIE Zhengsheng, et al. Effects of vegetation reclamation patterns on characteristics of soil collembola community in Baiyun Mountain, Guangzhou[J]. J Northeast For Univ, 2010, 38(4):94-97. [20] YAN Shaokui, SINGH A N, FU Shenglei, et al. A soil fauna index for assessing soil quality[J]. Soil Biol Biochem, 2012, 47(2):158-165. 62 -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.2017.01.009

下载:

下载: