-

中国经济社会的飞速发展促使人们更加注重绿色生态的人居环境质量,从而推动了草皮在城市中的需求不断增长。《中国林业和草原统计年鉴2018》数据显示:2018年中国草皮产量超过6万 hm2[1]。随着绿地面积的增加和质量的提升,草皮在园林绿化建设中的应用前景更加广阔[2]。但有研究表明:2018年中国耕地“非粮化”面积已达54.47万 km2,占全国耕地面积总量的32.3%,上海、浙江等6省(市)“非粮化”率已超过50.0%[3]。耕地“非粮化”问题与耕地保护的矛盾日益突出。浙江省水利厅资料显示:2018年浙江省全年河湖库塘清淤8 072.2万 m2[4]。目前,处理大量底泥的主要方法是干化处理后进行填埋,不仅占据了大片土地资源,还可能因为雨水冲刷造成土壤与水体的二次污染。另一方面,草坪草生产基本都是在同一耕地地块上重复进行,成坪后以草皮卷形式进行移植,不仅每次要带走2~3 cm的表层土壤,而且会对土壤的容重、密度和孔隙度等结构造成不可逆破坏,不利于耕地保护和可持续利用,因此,草坪生产耕地是“非粮化”整治重点关注领域之一[5]。无土栽培草皮具有种植灵活、可控性高、病虫害少、节水节肥等优越性,已在世界设施农业中被广泛采用[6]。将清淤产生的大量河湖库塘底泥代替耕地土壤用于草皮生产,不仅能有效解决“非粮化”引起的耕地挤占与土层破坏问题,而且能切实满足草皮等景观绿化种植的市场需求,还能协同解决河湖库塘底泥等有机固体废弃物的处理难题。

近年来,部分无土栽培基质出现了一些新的问题。块状岩棉很难分解,如果随意丢弃会污染环境;不可再生的天然泥炭被长期大量使用导致资源枯竭,并对地球湿地环境造成无法挽回的破坏;蛭石的结构松散、易破环,且使用周期短,维护成本高[7−8]。这促使栽培基质研究向环保型、经济型、技术型方向转变。选择资源循环利用、污染风险低且能解决环境问题的替代基质是主要发展方向[9]。在这种背景下,工农业有机固体废弃物基质研究备受关注[10]。沼渣是沼气发酵的产物,富含有机质、腐殖酸和氨基酸,以及速效养分和微量元素等,可以减少化肥使用,提高养殖业生态效益,降低草皮种植成本。生物质炭在土壤中的施用已经被证明可以改善土壤理化结构,固定土壤中重金属,有利于植物生长。将河道底泥、沼渣、生物质炭按一定比例复配制成种植基质,既符合绿色循环农业和可持续发展的要求,更具有实际的经济效益、环境效益和生态效益,是一种新的尝试。

本研究选取禾本科Gramineae冷季型草坪草匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’Agrostis stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’为研究对象,以清淤河道底泥为主料,复配沼渣和生物质炭,探究河道底泥为主料的基质对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’生物量、叶绿素、根系活力、可溶性糖、丙二醛、抗氧化保护酶的影响,为河道底泥等有机固体废弃物的资源化利用提供理论参考。

-

河道底泥取自钱塘江富阳段清淤产生的淤泥;沼渣取自杭州富阳某养殖场,为猪粪尿混合物经厌氧发酵(沼气工程)后产生的固体废渣;生物质炭以该养殖场猪粪为原料,经过500 ℃高温限氧炭化后得到的猪粪炭;耕作土取自试验基地旁耕地表层黏壤土,pH呈酸性。各供试材料理化指标如表1所示。

表 1 材料基础理化性质

Table 1. Basic physical and chemical properties of the materials used in the study

基质 酸碱度 电导率/(mS·cm−1) 容重/(g·cm−3) 总孔隙度/% 有机质/(g·kg−1) 全氮/(g·kg−1) 全磷/(g·kg−1) 全钾/(g·kg−1) 底泥 7.48 0.15 1.05 58.02 84.07 0.60 0.69 10.67 沼渣 6.54 2.49 0.51 72.41 309.50 15.23 24.69 3.71 生物质炭 9.40 1.26 0.63 59.85 699.63 20.83 21.91 14.50 耕作土 6.39 0.45 1.23 40.28 33.39 1.51 1.59 15.67 试验草种为禾本科冷季型草坪草匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’。该品种具有“百草之王”的美誉,是当前世界范围内品质最高的草皮品种,广泛应用于庭院、公园、广场等观赏性草坪,也是高尔夫球场的主要草种,有出色的耐低修剪、耐高温、抗病虫害以及卓越的抗寒能力。

-

本研究采用极端顶点设计,对河道底泥、沼渣、生物质炭进行混料,阶数为2[11]。基于底泥最大消耗原则(尽量多地消纳河道底泥),将上述3种基质的体积比例分别设定为50%≤底泥≤100%、0≤沼渣≤50%、0≤生物质炭≤10%。混料设计方案见表2,按体积比(v/v)进行混合。因目前草皮生产基本采用农田种植成坪后移植方式,故设置当地耕作表层土(0~20 cm)为对照组(ck)。

表 2 混料设计方案

Table 2. Scheme of a mixed material design

处理 点类型 底泥/% 沼渣/% 生物质炭/% 处理 点类型 底泥/% 沼渣/% 生物质炭/% 1 顶点 50.00 50.00 0 8 双混合 70.00 20.00 10.00 2 顶点 50.00 40.00 10.00 9 中心点 72.50 22.50 5.00 3 顶点 100.00 0 0 10 轴点 61.25 36.25 2.50 4 顶点 90.00 0 10.00 11 轴点 61.25 31.25 7.50 5 双混合 50.00 45.00 5.00 12 轴点 86.25 11.25 2.50 6 双混合 95.00 0 5.00 13 轴点 81.25 11.25 7.50 7 双混合 75.00 25.00 0 说明:数值为体积百分比。 试验在浙江科技大学校内试验基地(30°13′31″N,120°01′30″E,年日照时数为1 522.4 h)进行。坪床采用带排水孔规格为40 cm×40 cm×7 cm的育苗盘,底部铺30 g·m−2无纺布隔离,基质厚度为3.0 cm,上覆土厚度为0.5 cm。每处理重复3次。播种密度为12.0 g·m−2,发芽前每天浇水1次,发芽后7 d浇水1~2次,浇水量遵循见干见湿的原则。种植期间不额外施肥,待幼苗生长10 d左右,株高至10 cm后,按照1/3原则进行修剪[12]。本研究在开放自然环境下开展。2022年10月15日播种,共60 d,在第60天取样,测定植物理化指标。

-

生物量干质量采用实测称量法,叶绿素采用乙醇浸提法,可溶性糖采用蒽酮比色法,丙二醛采用硫代巴比妥酸比色法,过氧化氢酶采用钼酸铵比色法,超氧化物歧化酶采用氮蓝四唑法,过氧化物酶采用愈创木酚法,根系活力采用氯化三苯四氮唑法。生物量干质量在杀青烘干后测定,其余指标采用鲜样测定。具体测定方法参考《植物生理学实验指导》[13]。

-

将试验数据录入Excel 2013,并进行整理,用SPSS 26分析不同处理间差异显著性,Origin 2023制图。

-

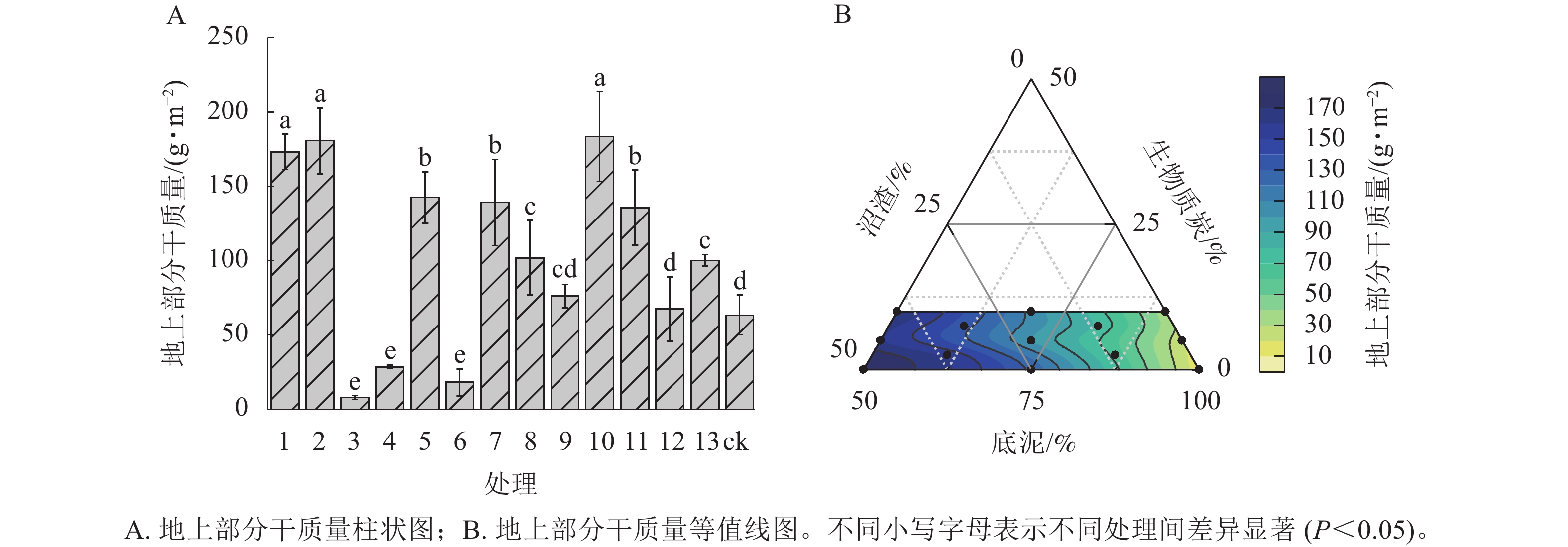

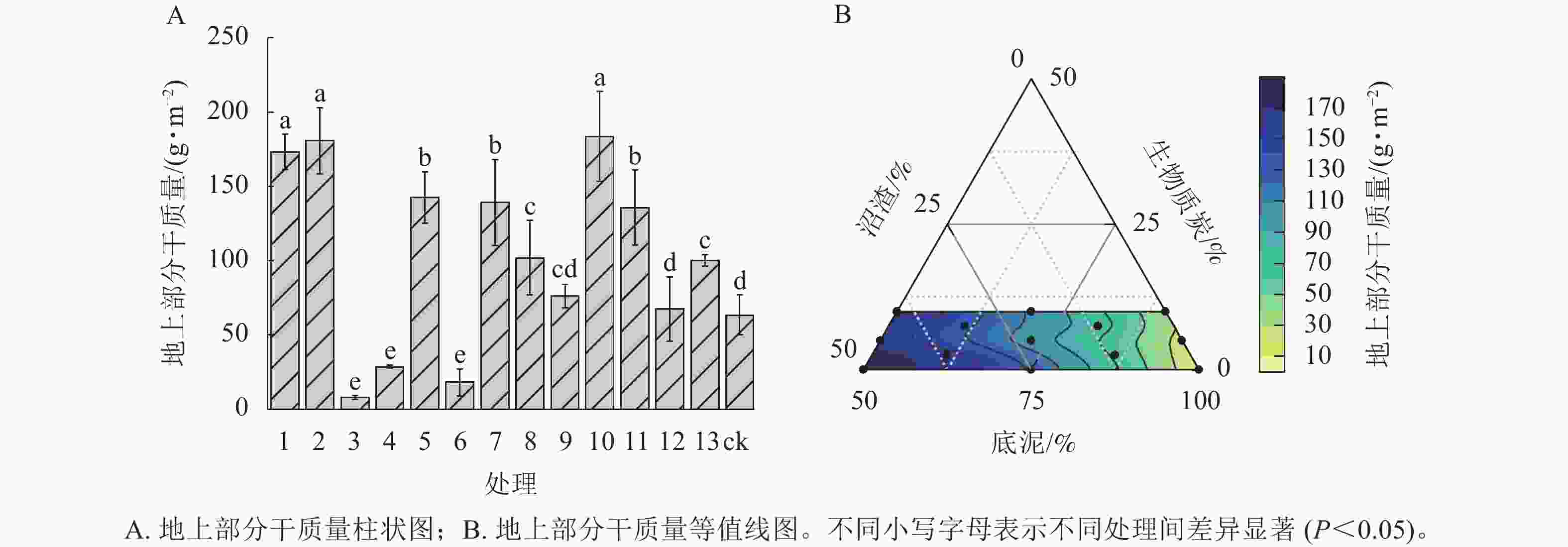

由图1A可见:处理1、处理2、处理10匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分干质量与ck相比差异最显著(P<0.05),分别比ck显著提高了172.98%、185.07%、189.27%,但三者之间差异不显著;处理3、处理4、处理6地上部分干质量显著低于ck (P<0.05),仅有ck地上部分干质量的12.46%、45.19%、28.50% (图1A)。主要原因是处理3、处理4、处理6未添加沼渣。随着混料基质中沼渣比例的增加,草皮地上部分干质量逐渐增加(图1B)。

-

由表3可知:各处理间匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素a、b质量分数分别为1.25~1.65和0.35~0.50 mg·g−1,低于ck。由于底泥性质更接近于黏土,故随着底泥比例的增加,叶绿素质量分数呈上升趋势。仅处理8和处理9叶绿素a/b略高于ck,但与ck相比,差异不显著。

表 3 不同处理间匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素的质量分数

Table 3. Chlorophyll contents in different treatments of A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’

处理 叶绿素a/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a+b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a/b 处理 叶绿素a/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a+b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a/b 1 1.33±0.01** 0.45±0.02** 1.77±0.03** 2.97±0.17** 8 1.49±0.04** 0.42±0.01** 1.91±0.04** 3.54±0.06 2 1.38±0.08** 0.46±0.03* 1.84±0.11** 3.00±0.04** 9 1.49±0.05** 0.42±0.05** 1.91±0.09** 3.54±0.41 3 1.65±0.10* 0.53±0.04 2.18±0.14* 3.10±0.08* 10 1.40±0.06** 0.44±0.05** 1.84±0.11** 3.20±0.21 4 1.28±0.02** 0.41±0.02** 1.69±0.03** 3.10±0.11* 11 1.50±0.03** 0.47±0.01* 1.97±0.03** 3.20±0.03 5 1.28±0.09** 0.45±0.03** 1.73±0.12** 2.87±0.04** 12 1.59±0.01** 0.48±0.01 2.07±0.02** 3.30±0.06 6 1.25±0.06** 0.37±0.04** 1.63±0.09** 3.36±0.28 13 1.40±0.04** 0.45±0.02** 1.85±0.07** 3.14±0.10* 7 1.33±0.18** 0.40±0.06** 1.74±0.25** 3.30±0.08 ck 1.81±0.10 0.53±0.03 2.33±0.14 3.42±0.02 说明:*表示不同处理与ck间差异显著(P<0.05),**表示不同处理与ck间差异极显著(P<0.01)。 -

由图2A可见:与ck相比,处理4的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分干质量最高,比ck显著提高了48.05% (P<0.05)。处理4与处理13基质上匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分干质量无显著差异,但2个处理显著高于其他处理(P<0.05),表明随着生物质炭比例逐渐增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分根系生物量逐渐增加,但随着沼渣比例的增加,地下部分干质量有降低趋势(图2B)。

-

由图3A可见:根系活力最强的是处理7的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’,为0.03×16.67 nkat·g−1,比ck (0.01×16.67 nkat·g−1)高约2.4倍;处理9、处理10次之,比ck高约2.0倍; 与ck相比,处理12根系活力无显著差异;处理6和处理13的根系活力显著低于ck (P<0.05),仅分别为ck的65.84%、83.69%。随着沼渣比例提高、底泥比例降低(图3B),基质容重逐渐降低,根系活力逐渐增强,能从基质中吸收更多矿质元素和水分供应地上部分的生长,这与图1B中显示的随着混料基质中沼渣比例的增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分干质量逐渐增加是一致的。混料基质中生物质炭比例的变化对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’根系活力的影响不明显。

-

由图4A可知:与ck相比,处理4的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’可溶性糖质量分数最高,比ck显著提高了70.95% (P<0.05),但与处理1、处理2相比差异不显著。处理3次之。处理5匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的可溶性糖质量分数显著低于ck (P<0.05),其余处理与ck相比无显著差异(图4A)。底泥比例为50.00%~100.00%时,随着底泥比例的增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’可溶性糖质量分数呈先降低后逐渐升高的趋势;同时,混料基质中沼渣比例过高或过低都会导致匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’可溶性糖质量分数升高,生物质炭比例的变化与沼渣导致的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’可溶性糖质量分数变化趋势基本一致(图4B)。

-

由图5A可知:处理7的匍匐剪股颖 ‘本特A-4’丙二醛质量摩尔浓度最高,为20.65 nmol·g−1,处理1次之,为20.89 nmol·g−1,分别比ck显著提高了24.16%、25.60% (P<0.05),但处理1和处理7之间差异不显著,其余处理匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’丙二醛质量摩尔浓度与ck相比无显著差异。由图5B可见:随着混料基质中底泥和生物质炭比例降低,沼渣比例增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’丙二醛质量摩尔浓度逐渐升高。

-

由表4可见:与ck相比,处理4、处理8、处理13的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化氢酶活性显著下降了42.33%、44.54%、46.45% (P<0.05),而处理7、处理9、处理11过氧化氢酶活性显著升高了35.02%、40.66%、25.23% (P<0.05),表明随着混料基质中生物质炭比例逐渐减少,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化氢酶活性逐渐增加。

表 4 不同处理间匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’抗氧化保护酶活性

Table 4. Antioxidant protective enzyme activities in different treatments of A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’

处理 过氧化氢酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)超氧化物歧化酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)过氧化物酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)处理 过氧化氢酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)超氧化物歧化酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)过氧化物酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)1 21.40±1.01 367.55±36.93** 697.92±42.87 8 12.43±2.48** 373.57±18.29** 594.51±39.24** 2 21.40±5.14 395.48±31.95** 793.27±21.60* 9 31.54±3.38** 430.98±18.62** 708.82±16.03 3 20.28±0.96 256.49±10.25* 659.04±28.40* 10 24.38±3.40 398.58±16.95** 764.31±29.50 4 12.93±0.79** 304.48±15.89 613.16±27.51** 11 28.08±0.98** 415.11±27.08** 828.98±36.13** 5 20.84±0.64 378.02±27.12** 715.14±27.55 12 18.19±1.71* 316.05±37.78 574.14±25.23** 6 17.81±1.89* 292.52±19.37 676.58±42.97 13 12.01±1.22** 319.52±15.16 787.36±43.58* 7 30.27±1.86** 392.23±10.75** 785.75±41.48 ck 22.42±2.64 304.96±29.18 729.52±34.36 说明:*表示不同处理与ck间差异显著(P<0.05);**表示不同处理与ck间差异极显著(P<0.01)。 处理3匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’中的超氧化物歧化酶活性显著降低,较ck显著下降了15.89% (P<0.05);其次是处理6,但匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的超氧化物歧化酶活性与对照组相比降低不显著。处理3、处理6的混料基质中底泥比例分别为100.00%和95.00%,表明混料基质中底泥比例提高会降低匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的超氧化物歧化酶活性。

与ck相比,处理11的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化物酶活性升幅最大,达极显著差异水平(P<0.01),处理2、处理13的匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化物酶活性较ck显著升高了8.74%和7.93% (P<0.05);但处理3、处理4、处理8和处理12与ck相比,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化物酶活性显著下降,其中处理12降幅最大,达极显著水平(P<0.01)。随着混料基质中沼渣比例的增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化物酶活性出现先缓慢增加再减少的趋势。当沼渣比例在30.00%~40.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’过氧化物酶活性显著上升。

-

地上部分生物量的大小能够在一定程度上反映植物的生长和光合作用能力,叶绿素质量分数的变化是体现植物遭受胁迫损害的重要指标之一。本研究中,基质中沼渣的施用是影响匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量的主要因素,加入适量的沼渣(36.25%~50.00%)能够显著提高其地上部分生物量。这与HAMMERSCHMIEDT等[14]发现的沼渣施用显著增加了莴苣Lactuca sativa地上部分生物量的结果相似,并且随着沼渣在基质中比例逐渐增加,河道底泥比例逐渐降低,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量逐渐增加。本研究中沼渣为某养殖场猪粪尿混合物经厌氧发酵后的固体废渣,可以作为有机肥原料使用,改善基质肥力,为植物茎叶生长提供必要的营养元素。CHEN等[15]研究表明:生物质炭的施用能够提高作物的生物量,但本研究中生物质炭对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量影响不明显。主要原因可能是猪粪沼渣炭化后,产物中氮等营养元素因高温逸失,磷、钾等营养与原料沼渣中赋存形态相比有效性降低,短期内(本研究为60 d),其营养效应还未显现。冯树林等[16]研究表明:植物叶绿素质量分数与土壤水分有较大关系。混料基质匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素质量分数均低于ck,可能是混料基质容重低于传统耕作土,保水性能相对也低,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶片水分亏缺,叶绿素结构受到一定影响,光合作用相关蛋白质量分数降低,叶绿素降解速度高于合成速度。生物质炭虽然有较好的保水性能,但由于其占比较低,保水效果不明显。在混料基质配比中,当底泥比例为50.00%~75.00%、沼渣比例为36.25%~50.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量和绿度较好。

在草皮生长过程中,地下部分是其吸收水分和矿质元素的主要器官。地下部分生物量越多,越能够促进草皮生长[17]。本研究中,基质中生物质炭的比例是影响匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分生物量的主要因素,加入适量的生物质炭(5.00%~10.00%)能够有效提高其地下部分生物量促进匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的根系生长,表明生物质炭的特殊多孔结构一定程度上改变了基质结构,这与XIANG等[18]研究生物炭施用能显著增加根系生物量的结果相一致。此外,PEI等[19]研究表明:生物质炭的添加能够增加根系分泌物的释放,如氨基酸、植物生长素和脱落酸等,这些根系分泌物能够进一步促进根系的伸长,为植物提供更有利的生长条件,并且随着沼渣比例的提高,根系活力逐渐增强。本研究中,混料基质容重低于耕作土,表明基质松散、孔隙多、透气性好,有利于植物生长。在几种混料基质配比中,当生物质炭比例为5.00%~10.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分生物量较高,根系活力较好;底泥比例为75.00%~100%,沼渣比例为0~25.00%时,更有助于地下部分生长;底泥比例为50.00%~75.00%,沼渣比例为20.00%~50.00%时,根系活力更旺盛。

增加草皮地上部分生物量,可以促进其光合、呼吸和蒸腾作用,提高草坪草的观赏性;增加其地下生物量,则能够促进草皮对水分的固定、吸收,进而促进草皮的生长。通过调整基质中底泥、沼渣和生物质炭的混配比例,可以优化草皮的生长,促进地上和地下部分的协调生长。

-

可溶性糖是重要的渗透调节物质。植物可以通过积累可溶性糖,增强细胞的渗透调节能力,应对外界环境影响[20]。本研究中,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’ 可溶性糖质量分数随着混料基质中沼渣和生物质炭比例的增加,整体呈先降低后增加的趋势,表明添加适当比例(2.50%~7.50%)的生物质炭,能够降低其可溶性糖质量分数,缓解植物受到的胁迫影响,这与HAFEZ等[21]研究水分胁迫下生物质炭处理降低了大麦Hordeum vulgare的可溶性糖质量分数的结果相近。同时,本研究结果也显示:随着底泥比例的增加、沼渣比例的降低,可溶性糖质量分数呈上升趋势。在混料基质配比中,当底泥比例为50.00%~75.00%,沼渣比例为25.00%~36.25%,生物质炭比例为2.50%~7.50%时,草皮可溶性糖质量分数较为适中。

丙二醛是植物膜脂过氧化的最终产物,其质量摩尔浓度可以反映植物所受胁迫的程度[22]。本研究中,随着底泥比例降低,沼渣比例增加,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’抗氧化酶活性有所上升,清除了植株体内部分活性氧自由基,但仍有部分过剩的自由基,引发膜脂氧化作用,从而导致丙二醛积累。同时,本研究结果也显示:混料基质中增加生物质炭的比例,能够有效降低丙二醛质量摩尔浓度。这与刘易等[23]的研究结果类似,其发现生物质炭处理土壤后玉米Zea mays丙二醛质量摩尔浓度降低。但当生物质炭添加比例过低(0~2.50%)时,不能发挥其降低丙二醛的效果。在混料基质配比中,当底泥比例为75.00%~100%、沼渣比例为0~30.00%、生物质炭比例为2.50%~10.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特 A-4’丙二醛质量摩尔浓度较为适中。

过氧化氢酶、超氧化物歧化酶、过氧化物酶是植物体内重要的抗氧化保护酶。在一定范围内,过氧化氢酶、超氧化物歧化酶和过氧化物酶的活性与植物所受胁迫的程度呈正相关[24]。本研究中,底泥的性质接近黏土,以其为主料添加生物质炭的基质均可缓解匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的受胁迫程度。随着沼渣添加比例的增加,过氧化氢酶、超氧化物歧化酶、过氧化物酶的活性变化趋势相近,呈先增加后降低,但依然高于基质中未添加沼渣时的活性,说明沼渣含有的一些有害物质,重金属、抗生素、病原微生物等也会随着沼渣比例的增加而增加。这些有害物质超过植物耐受程度时,可能会破坏植物的保护酶系统,导致酶活性降低,而对植物的生长产生不利影响。因此,在实际生产中使用沼渣时需要对其中的有害物质进行检测,以确保植物健康生长。适量生物质炭的添加能在降低匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’体内丙二醛质量摩尔浓度的同时,降低过氧化物酶和超氧化物歧化酶的活性。这与FARHANGI-ABRIZ等[25]的研究结果相近,其发现添加生物质炭处理的盐胁迫大豆Glycine max幼苗抗氧化酶活性显著降低。适当比例的底泥、沼渣和生物质炭能够通过改善基质理化性质,降低植物遭受胁迫程度,使草皮生长良好。在混料基质配比中,当底泥比例为72.50%~100%、沼渣比例为0~20.00%、生物质炭比例为2.50%~10.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特 A-4’过氧化氢酶活性适中;当底泥比例为81.25%~100%、沼渣比例为0~11.25%、生物质炭比例为0~7.50%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特 A-4’超氧化物歧化酶活性适中;当底泥比例为81.25%~100%、沼渣比例为0~22.50%、生物质炭比例为在0~10.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特 A-4’过氧化物酶活性较为适中。

-

从混料基质对生长的影响分析,比例为75.00%的底泥,对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分、地下部分生物量及根系活力的影响较为均衡;从混料基质对生理指标的影响分析,与传统耕作土相比,底泥作为替代基质主料对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’生长不会产生不利影响。从这个角度出发,底泥比例大于75.00%较为适宜。

生物质炭比例为5.00%~10.00%的混料基质,对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分、地下部分生物量及根系活力的影响较好;但从对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’ 可溶性糖、丙二醛和抗氧化酶等生理指标的影响看,生物质炭的比例为2.50%~5.00%比较合适。

因此,如果混料基质以底泥、生物质炭、沼渣混合,底泥比例选择为75.00%,生物质炭比例为5.00%,则混料基质中沼渣比例为20.00%。在此配比下,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分干质量和地下部分干质量分别显著提高了58.53%和17.19%,与ck相比均达显著差异水平,根系活力提升了近1倍(91.55%),但匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素a、b质量分数分别降低了21.52%和19.49%。另外,与ck相比,混料基质除引起匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’超氧化物歧化酶活性升高外(28.66%),对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’可溶性糖质量分数、丙二醛质量摩尔浓度及过氧化氢酶和过氧化物酶活性的影响不明显。综上所述,在此配比下,混料基质相较于传统耕作土对匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’生长具有显著的促进作用,同时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’生理抗性反应小。

-

以底泥为主料,掺混适当比例的生物质炭、沼渣的基质代替耕作土进行匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’种植是可行的,掺混沼渣能够有效提高匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量和根系活力,生物质炭可有效提高匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分生物量。与传统耕作土相比,当混料基质中底泥占75.00%、沼渣占20.00%、生物质炭占5.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的生长表现良好。

Effects of river sediment as the main substrate on the growth and physiological indexes of Agrostis stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’

-

摘要:

目的 河湖库塘清淤底泥用于草皮等高经济价值园林绿化植物生产,既能有效解决挤占耕地与破坏耕层问题,又能协同解决底泥等有机固体废弃物的处理难题。 方法 通过混料设计,按照底泥最大消耗原则,设置底泥、沼渣、生物质炭3种原料用量比例(体积比)分别为50%≤底泥≤100%、0≤沼渣≤50%、0≤生物质炭≤10%,共13个处理,同时设置耕作土为对照组,测定匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’Agrostis stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’生长指标(生物量干质量、叶绿素、根系活力)和生理指标(可溶性糖、丙二醛、抗氧化保护酶),明确河道底泥为主料的基质代替传统耕作土种植匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’的可行性和适宜性。 结果 与耕作土(对照)相比,混料基质中3种原料比例(体积比)底泥为75.00%、沼渣为20.00%、生物质炭为5.00%时,匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分和地下部分干质量分别显著提高了58.53%和17.19% (P<0.05),根系活力极显著提高了近1倍 (P<0.01),但匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素a、b质量分数分别均极显著降低了约20.00% (P<0.01)。另外,混料基质使匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’超氧化物歧化酶活性极显著升高28.66% (P<0.01),对植株体内可溶性糖质量分数、丙二醛质量摩尔浓度及过氧化氢酶活性和过氧化物酶活性影响不显著。 结论 以底泥为主料,掺混适当比例的生物质炭、沼渣的基质代替耕作土种植匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’是可行的,掺混的沼渣能够有效提高匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地上部分生物量和根系活力,生物质炭可有效提高匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’地下部分生物量。图5表4参25 -

关键词:

- 河道底泥 /

- 匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’ /

- 基质 /

- 生理指标 /

- 生物量

Abstract:Objective The dredging sediment from rivers, lakes, reservoirs and ponds can be used for the production of high-economic value landscape plants such as turf, which can not only solve the problem of occupying cultivated farmland and destroying top soil layer, but also solve the treatment and disposal problem of organic solid waste such as sediment. Method Based on the mixed material design and the principle of maximum consumption of river sediment, the proportion of the three raw materials, namely sediment, biogas residue, and biochar, was set to be 50%≤sediment≤100%, 0≤biogas residue≤50%, and 0≤biochar≤10%, respectively, totaling 13 treatments. Meanwhile, cultivated soil was set as the control, and the growth indicators (biomass dry mass, chlorophyll, root activity) and physiological indicators (soluble sugar, malondialdehyde, antioxidant protective enzymes) were measured to explore the feasibility and suitability of planting Agrostis stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’ with the substrate of river sediment as the main material instead of the traditional cultivated soil. Result Compared with the control, the dry weight of above ground part and underground part of A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’ significantly increased by 58.53% and 17.19%, respectively (P<0.05) and the root activity nearly doubled (P<0.01) when the proportion of sediment in the mixed substrate was 75.00%, the proportion of biogas residue was 20.00%, and the proportion of biochar was 5.00%, but the content of chlorophyll a and b in plants decreased by approximately 20.00% (P<0.01). In addition, the mixed substrate significantly increased superoxide dismutase activity (28.66%, P<0.01), but had no significant effect on the contents of soluble sugar and malondialdehyde, catalase activity and peroxidase activity in plants. Conclusion It is feasible to use river sediment as the main material, mixed with an appropriate proportion of biogas residue and biochar as a substrate instead of cultivated soil for A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’ planting. The mixed biogas residue can effectively increase the aboveground biomass and root vitality of the turf grass, while biochar can effectively increase the underground biomass of the grass. [Ch, 5 fig. 4 tab. 25 ref.] -

Key words:

- river sediment /

- Agrostis stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’ /

- turf substrate /

- physiological indexes /

- biomass

-

表 1 材料基础理化性质

Table 1. Basic physical and chemical properties of the materials used in the study

基质 酸碱度 电导率/(mS·cm−1) 容重/(g·cm−3) 总孔隙度/% 有机质/(g·kg−1) 全氮/(g·kg−1) 全磷/(g·kg−1) 全钾/(g·kg−1) 底泥 7.48 0.15 1.05 58.02 84.07 0.60 0.69 10.67 沼渣 6.54 2.49 0.51 72.41 309.50 15.23 24.69 3.71 生物质炭 9.40 1.26 0.63 59.85 699.63 20.83 21.91 14.50 耕作土 6.39 0.45 1.23 40.28 33.39 1.51 1.59 15.67 表 2 混料设计方案

Table 2. Scheme of a mixed material design

处理 点类型 底泥/% 沼渣/% 生物质炭/% 处理 点类型 底泥/% 沼渣/% 生物质炭/% 1 顶点 50.00 50.00 0 8 双混合 70.00 20.00 10.00 2 顶点 50.00 40.00 10.00 9 中心点 72.50 22.50 5.00 3 顶点 100.00 0 0 10 轴点 61.25 36.25 2.50 4 顶点 90.00 0 10.00 11 轴点 61.25 31.25 7.50 5 双混合 50.00 45.00 5.00 12 轴点 86.25 11.25 2.50 6 双混合 95.00 0 5.00 13 轴点 81.25 11.25 7.50 7 双混合 75.00 25.00 0 说明:数值为体积百分比。 表 3 不同处理间匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’叶绿素的质量分数

Table 3. Chlorophyll contents in different treatments of A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’

处理 叶绿素a/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a+b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a/b 处理 叶绿素a/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a+b/

(mg·g−1)叶绿素a/b 1 1.33±0.01** 0.45±0.02** 1.77±0.03** 2.97±0.17** 8 1.49±0.04** 0.42±0.01** 1.91±0.04** 3.54±0.06 2 1.38±0.08** 0.46±0.03* 1.84±0.11** 3.00±0.04** 9 1.49±0.05** 0.42±0.05** 1.91±0.09** 3.54±0.41 3 1.65±0.10* 0.53±0.04 2.18±0.14* 3.10±0.08* 10 1.40±0.06** 0.44±0.05** 1.84±0.11** 3.20±0.21 4 1.28±0.02** 0.41±0.02** 1.69±0.03** 3.10±0.11* 11 1.50±0.03** 0.47±0.01* 1.97±0.03** 3.20±0.03 5 1.28±0.09** 0.45±0.03** 1.73±0.12** 2.87±0.04** 12 1.59±0.01** 0.48±0.01 2.07±0.02** 3.30±0.06 6 1.25±0.06** 0.37±0.04** 1.63±0.09** 3.36±0.28 13 1.40±0.04** 0.45±0.02** 1.85±0.07** 3.14±0.10* 7 1.33±0.18** 0.40±0.06** 1.74±0.25** 3.30±0.08 ck 1.81±0.10 0.53±0.03 2.33±0.14 3.42±0.02 说明:*表示不同处理与ck间差异显著(P<0.05),**表示不同处理与ck间差异极显著(P<0.01)。 表 4 不同处理间匍匐剪股颖‘本特A-4’抗氧化保护酶活性

Table 4. Antioxidant protective enzyme activities in different treatments of A. stolonifera ‘PENN A-4’

处理 过氧化氢酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)超氧化物歧化酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)过氧化物酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)处理 过氧化氢酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)超氧化物歧化酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)过氧化物酶/

(×16.67 nkat·g−1)1 21.40±1.01 367.55±36.93** 697.92±42.87 8 12.43±2.48** 373.57±18.29** 594.51±39.24** 2 21.40±5.14 395.48±31.95** 793.27±21.60* 9 31.54±3.38** 430.98±18.62** 708.82±16.03 3 20.28±0.96 256.49±10.25* 659.04±28.40* 10 24.38±3.40 398.58±16.95** 764.31±29.50 4 12.93±0.79** 304.48±15.89 613.16±27.51** 11 28.08±0.98** 415.11±27.08** 828.98±36.13** 5 20.84±0.64 378.02±27.12** 715.14±27.55 12 18.19±1.71* 316.05±37.78 574.14±25.23** 6 17.81±1.89* 292.52±19.37 676.58±42.97 13 12.01±1.22** 319.52±15.16 787.36±43.58* 7 30.27±1.86** 392.23±10.75** 785.75±41.48 ck 22.42±2.64 304.96±29.18 729.52±34.36 说明:*表示不同处理与ck间差异显著(P<0.05);**表示不同处理与ck间差异极显著(P<0.01)。 -

[1] 张建龙. 中国林业和草原统计年鉴(2018)[M]. 北京: 中国林业出版社, 2019. ZHANG Jianlong. China Forestry and Grassland Statisical Yearbook (2018) [M]. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House, 2019. [2] 单华佳, 李梦璐, 孙彦, 等. 近10年中国草坪业发展现状[J]. 草地学报, 2013, 21(2): 222 − 229. SHAN Huajia, LI Menglu, SUN Yan, et al. Recent development of turf grass industry in China [J]. Acta Agrestia Sinica, 2013, 21(2): 222 − 229. [3] 杨翠红, 林康, 高翔, 等. “十四五”时期我国粮食生产的发展态势及风险分析[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2022, 37(8): 1088 − 1098. YANG Cuihong, LIN Kang, GAO Xiang, et al. Analysis on development and risks of China’ s food production during 14th five-year plan period [J]. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2022, 37(8): 1088 − 1098. [4] 浙江省水利厅. 全省水利统计简报(2018年度)[EB/OL]. 2019-02-12 [2023-12-25]. https://slt.zj.gov.cn/art/2019/2/12/art_1229232728_1987881.html. Department of Water Resources of Zhejiang Province. Provincial Water Conservancy Statistics Briefing (2018) [EB/OL]. 2019-02-12 [2023-12-25]. https://slt.zj.gov.cn/art/2019/2/12/art_1229232728_1987881.html. [5] 崔建宇, 慕康国, 胡林, 等. 北京地区草皮卷生产对土壤质量影响的研究[J]. 草业科学, 2003, 20(6): 68 − 72. CUI Jianyu, MU Kangguo, HU Lin, et al. Studies on the effects of sod-production on soil quality in Beijing area [J]. Pratacultural Science, 2003, 20(6): 68 − 72. [6] 崔高磊, 徐翠, 罗富成, 等. 无土草皮生长介质的研究与应用进展[J]. 草学, 2020(6): 7 − 12, 24. CUI Gaolei, XU Cui, LUO Fucheng, et al. Research and application progress of soilless turf growth substrate [J]. Journal of Grassland and Forage Science, 2020(6): 7 − 12, 24. [7] DUNN C, FREEMAN C. Peatlands: our greatest source of carbon credits? [J]. Carbon Management, 2011, 2(3): 289 − 301. [8] CLEARY J, ROULET N T, MOORE T R. Greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian peat extraction, 1990−2000: a life-cycle analysis [J]. AMBIO, 2005, 34(6): 456 − 461. [9] 肖超群, 郭小平, 刘玲, 等. 绿化废弃物堆肥配制屋顶绿化新型基质的研究[J]. 浙江农林大学学报, 2019, 36(3): 598 − 604. XIAO Chaoqun, GUO Xiaoping, LIU Ling, et al. Greening waste compost as a new substrate for green roofs [J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2019, 36(3): 598 − 604. [10] RAVIV M. Composts in growing media: what’ s new and what’ s next? [J]. Acta Horticulturae, 2013, 982: 39 − 52. [11] 马逢时, 周暐, 刘传冰. 六西格玛管理统计指南: MINITAB使用指导[M]. 北京: 中国人民大学出版社, 2018. MA Fengshi, ZHOU Wei, LIU Chuanbing. Six Sigma Management Statistics Guide: MINITAB Usage Guide [M]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2018. [12] 郑凯, 杨新根. 山西省草坪建植和养护管理[J]. 山西农业科学, 2010, 38(11): 98 − 100. ZHENG Kai, YANG Xin’gen. The technique of lawns establishment, management and maintenance in Shanxi Province [J]. Journal of Shanxi Agricultural Sciences, 2010, 38(11): 98 − 100. [13] 高俊凤. 植物生理学实验指导[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2006. GAO Junfeng. Plant Physiology Experiment Guide [M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2006. [14] HAMMERSCHMIEDT T, KINTL A, HOLATKO J, et al. Assessment of digestates prepared from maize, legumes, and their mixed culture as soil amendments: effects on plant biomass and soil properties [J/OL]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022, 13: 1017191[2023-12-25]. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1017191. [15] CHEN Wenfu, MENG Jun, HAN Xiaori, et al. Past, present, and future of biochar [J]. Biochar, 2019, 1(1): 75 − 87. [16] 冯树林, 周婷, 王军利. 几种野生百合叶绿素和氮对干旱胁迫的响应特征研究[J]. 辽宁农业科学, 2023(4): 6 − 11. FENG Shulin, ZHOU Ting, WANG Junli. Research on the response characteristics of chlorophyll and nitrogen content of several typical wild lilies to drought stress [J]. Liaoning Agricultural Sciences, 2023(4): 6 − 11. [17] 张卫红, 刘大林, 苗彦军, 等. 西藏3种野生牧草苗期对干旱胁迫的响应[J]. 生态学报, 2017, 37(21): 7277 − 7285. ZHANG Weihong, LIU Dalin, MIAO Yanjun, et al. Drought stress responses of the seedlings of three wild forages in Tibet [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2017, 37(21): 7277 − 7285. [18] XIANG Yangzhou, DENG Qi, DUAN Honglang, et al. Effects of biochar application on root traits: a meta-analysis [J]. Global Change Biology Bioenergy, 2017, 9(10): 1563 − 1572. [19] PEI Junmin, LI Jinquan, FANG Changming, et al. Different responses of root exudates to biochar application under elevated CO2 [J/OL]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2020, 301: 107061[2023-12-25]. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2020.107061. [20] 刘训. 提高狗牙根抗旱性外源物质配方的筛选研究[D]. 武汉: 中国科学院, 2016. LIU Xun. Exogenous Application of Substances Improves the Drought Tolerance of Bermudagras [D]. Wuhan: Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2016. [21] HAFEZ Y M, ATTIA K, ALAMERY S, et al. Beneficial effects of biochar and chitosan on antioxidative capacity, osmolytes accumulation, and anatomical characters of water-stressed barley plants [J/OL]. Agronomy, 2020, 10(5): 630[2023-12-25]. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10050630. [22] 刘亚丽, 王庆成, 刘爽, 等. 水分胁迫对脂松苗木针叶质膜透性和保护酶活性的影响[J]. 植物研究, 2011, 31(1): 49 − 55. LIU Yali, WANG Qingcheng, LIU Shuang, et al. Effects of water stress on plas ma membrane per meability and protective enzyme activities of red pine seedlings needles [J]. Bulletin of Botanical Research, 2011, 31(1): 49 − 55. [23] 刘易, 孟阿静, 黄建, 等. 生物质炭输入对盐胁迫下玉米植株生物学性状的影响[J]. 干旱地区农业研究, 2018, 36(2): 16 − 22, 249. LIU Yi, MENG Ajing, HUANG Jian, et al. Effect of biomass carbon input on corn biological index cultivated under saline stress [J]. Agricultural Research in the Arid Areas, 2018, 36(2): 16 − 22, 249. [24] 王鹤冰, 向华丰, 张洪成, 等. 不同性型水果黄瓜内过氧化物酶及同工酶的差异性分析[J]. 南方农业, 2021, 15(4): 52 − 54. WANG Hebing, XIANG Huafeng, ZHANG Hongcheng, et al. Difference analysis of endoperoxidase and isoenzymes in cucumber with different sex types [J]. South China Agriculture, 2021, 15(4): 52 − 54. [25] FARHANGI-ABRIZ S, TORABIAN S. Antioxidant enzyme and osmotic adjustment changes in bean seedlings as affected by biochar under salt stress [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2017, 137: 64 − 70. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20240157

下载:

下载: