-

植物组织培养是在无菌条件下通过调控外植体生长环境和植物激素,诱导细胞脱分化与再分化,实现高效无性再生的技术。这项技术是植物生物技术的重要基础工具,在作物遗传改良、快速繁殖、种质资源保存和基因工程等方面发挥重要作用。植物离体细胞无限增殖的实现,标志着植物组织培养作为一门实验技术的诞生[1−2]。生长素和细胞分裂素的不同浓度配比对不定根和不定芽再生至关重要,显示植物组织培养体系已经成熟[3]。此后,组织培养不仅成为研究细胞全能性的核心工具,也是推动农业生物技术进步的关键技术[4]。

植物组织培养主要有器官发生和体细胞胚胎发生 2种途径。器官发生是指外植体在激素调控下形成愈伤组织,并进一步分化为不定根或不定芽;体细胞胚胎发生则是不经配子由体细胞直接或间接形成类似合子胚的结构,最终发育成完整植株[5−7]。在木本植物中,器官发生更具普适性。尽管体细胞胚胎发生已在松树Pinus spp.、桉树Eucalyptus spp.、马褂木Liriodendron chinense等少数树种中成功应用,但其发生效率、基因型依赖性以及再生苗的转化等问题仍限制了其广泛推广[8−9]。

目前,木本植物器官发生仍存在基因型依赖、易褐化、难生根及分子机制不清晰等问题。随着分子生物学与基因组学的推进,关于木本植物器官发生的调控网络不断完善,其中转录因子如WUSCHEL(WUS)、WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX(WOX)在脱分化与再分化中发挥重要作用[10−12],生长素与细胞分裂素等激素信号与表观遗传修饰(如DNA甲基化、组蛋白乙酰化)之间的耦合调控被证实对再生至关重要[13−14]。因此,有必要对木本植物组织培养中的器官发生途径、关键影响因素与分子机制进行系统梳理,以加深对再生机制的理解,并为突破再生效率低瓶颈提供理论参考,期望为提升木本植物再生效率与遗传改良应用提供科学依据。

-

木本植物再生体系中,外植体的组织类型与发育阶段是决定再生成功与否的首要因素,一般而言,幼嫩组织(如幼叶、茎尖、下胚轴)再生能力更强、褐化更少,而成熟组织因细胞分化程度高、酚类物质积累多,往往更难诱导且易褐化[15−16]。例如,赤桉Eucalyptus camaldulensis幼嫩子叶的愈伤组织诱导潜力显著高于成熟材料[17]。因此,在建立再生体系时,可系统比较2~3种不同类型外植体的诱导率、再生率、褐化率与污染率,形成全面的外植体筛选数据表。

对于易褐化、难再生材料,操作流程至关重要。须采用“三快”流程,即快速取材、快速消毒和快速接种,最大限度地缩短外植体离体后的伤口暴露时间,从而减少酚类物质氧化。此外,在器官发生途径中,不同外植体对植物生长调节剂的响应也存在差异。例如诱导芽再生时通常选择腋芽或带节茎段,而诱导根形成时,下胚轴和叶柄是更理想的选择,两者对生长素的短时处理更敏感[18]。表1归纳总结了不同初始外植体与培养体系的关键参数及结果。

表 1 不同外植体与培养体系的关键参数及结果

Table 1. Key parameters and outcomes across different explant and culture systems

物种 外植体 培养基 植物生长调节剂组合

(诱导/分化)温度/℃ 光强/lx 诱导率/% 异常率/% 文献 银杉Cathaya argyrophylla 成熟胚 DCR/½MS 0.5 6-BA/0.2 NAA+0.5 IBA 25±2 2000 ~3000 >60 <30 (未发育率) [19] 高山杜鹃Rhododendron

chrysanthum叶片 WPM/WPM 0.5~1.5 TDZ+0.5 NAA/

0.5 IBA+1.0~1.5 NAA24±2 1500 ~1800 100 0 (褐化率) [20] 牡丹Paeonia suffruticosa 花丝 MSB/½WPN 0.5 2,4-D+0.25 TDZ/1.0 IBA+

0.1 NAA+1.0 VB2+1.0 腐胺25±1 >90 <10 (褐化率) [21] 胡桃楸Juglans mandshurica 腋芽茎段 WPM/½MS 2.0 6-BA+0.01 IBA/1.0 IBA 25±2 2 000 80 20 (褐化率) [22] 说明:植物生长调节剂前的数值单位为mg·L−1。 -

基础培养基的无机盐强度、氮源形式($ {\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}/{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-}$)与微量元素比是影响器官发生效率与质量的关键因素[23]。相较于MS培养基,WPM、DKW等专用培养基因其较低的总离子强度和铵态氮比例,能更有效地减轻木本植物的生理胁迫,从而在芽诱导与生根阶段表现出更高的效率[22−23]。实践中可采用阶段化培养基配方。例如胡桃楸Juglans mandshurica在腋芽茎段组织培养中,诱导和继代阶段均采用WPM培养基,而在生根阶段,转为½MS培养基,使得生根率最高[22]。

碳源不仅为生长提供能量,也作为渗透调节物质显著影响器官发育进程。蔗糖是最常用的碳源,但其最佳浓度与形式因物种和培养阶段而异。例如在欧洲李子Prunus domestica中,以质量分数为3%蔗糖对枝叶的促进效果最优[24];而在枸杞Lycium ruthenicum中,质量分数为4%的蔗糖可在无激素条件下有效诱导愈伤组织增殖与器官发生[25]。此外,在不定芽继代增殖阶段添加蔗糖的效果优于果糖,而在生根阶段,果糖表现出比葡萄糖和蔗糖更好地促进效果[26−27]。铁源类型(如Fe-EDTA/Fe-EDDHA)与微量元素(如Zn/Cu)比例同样也会影响培养稳定性和褐化程度[22, 27]。因此,在方法中应明确列出盐浓度、糖含量、铁源等关键参数[28],以确保实验的可重复性。表2比较了常用培养基的关键参数与适用阶段。

表 2 常用培养基关键参数对比(木本器官发生导向)

Table 2. Comparison of key parameters of commonly used culture media (woody organogenesis orientation)

培养基 总盐强度

(相对MS)${\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}/{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-} $ 微量元素(铁源) 推荐阶段 注意事项 具体案例 MS 1.0 高铵 Fe-EDTA 通用 高铵易导致褐化,

慎用全强度培养基茶树Camellia sinensis茎段[29]

不定芽诱导、增殖½MS/

改良MS0.5~0.8 中/低铵 Fe-EDTA/

Fe-EDDHA芽分化和伸长阶段;

生根培养降盐降糖减轻玻璃化;

适合对铵敏感木本植物银白杨Populus alba腋芽茎段[30]

不定芽生根WPM 0.6~0.7 低铵 微量元素优化;

Fe-EDTA促进枝条和根系生长 木本优选,

降低褐化、玻璃化胡桃楸Juglans mandshuriea腋芽

茎段[22]不定芽诱导DKW ≈0.8 中铵 ${\mathrm{SO}}_{4}^{2-} $较高;

Fe-EDTA生根;体细胞胚胎发生 与TDZ或IBA协同使用

效果更佳核桃Juglans regia带芽茎段[31]

不定芽诱导说明:“总盐强度”数值是以MS培养基的总离子浓度为基准(1.0)的无量纲相对比值,用于直观比较不同培养基的宏观渗透压与营养负荷。 -

生长素与细胞分裂素的比例以及处理时序直接决定器官发生的方向性与质量[32]。须针对植物精确调整细胞分裂素和生长素的类型与质量浓度,才能实现最佳的芽增殖和生根效果[33]。总体而言,细胞分裂素比例高促进芽的生长,生长素比例高促进根的生长[3, 34]。在木本体系中,0.1~1.0 mg·L−1噻苯脲(TDZ)显著促进芽原基形成,但易导致芽团致密与继代困难[32, 35]。在分化或伸长期,改用6-苄氨基腺嘌呤(6-BA)、激动素(KT)或降低TDZ质量浓度以改善伸长品质,如,在‘阳光玫瑰’葡萄 Vitis ‘Shine Muscat’中,采用TDZ启动分芽,再通过降低TDZ质量浓度或改用6-BA以优化芽体质量[33]。在根诱导阶段,常采用萘乙酸(NAA)或吲哚丁酸(IBA)单独处理,并常在培养基中添加活性炭以吸附酚类物质,从而显著提高生根质量[30],这在柑橘Citrus spp.[36]和榛子Corylus spp.[37]等多种木本植物的生根培养中均得到有效验证。

-

环境因子的精细化与阶段性调控是提升植物器官发生质量的关键。光照环境根据培养阶段不同进行调整,在诱导期采用弱光或短日照以减少胁迫,分化期延长光照时间至14~16 h,并采用复合光谱以提高芽质量[38−39]。温度通常维持在22~25 ℃,特定阶段可微调1~2 ℃,如银白杨Populus alba愈伤组织诱导阶段最佳温度为25 ℃,生根阶段最佳温度为(23±2) ℃,炼苗移栽阶段最佳温度为19~22 ℃[40]。培养基pH在灭菌前调至5.6~5.8。

为应对常见生理障碍,可针对性采取措施。为减轻玻璃化现象,可通过适当提高凝固剂浓度,或添加甘露醇、山梨醇等渗透调节剂以降低细胞水势,从而抑制玻璃苗的发生。促进生根可采用“高渗诱导-逐步降渗”法,即通过在诱导初期提高培养基渗透压以刺激根原基分化,随后转至低渗培养基中促进根系的伸长与成熟[26]。抑制褐化可在初代培养基中添加抗氧化剂,如聚乙烯吡咯烷酮(PVP)、抗坏血酸(AsA)或活性炭等,以吸附酚类物质或清除活性氧来提高存活率[16, 23]。如在欧洲丁香Syringa vulgaris细胞悬浮培养中,添加100 mg·L−1PVP和75 mg·L−1AsA能大幅提升细胞增殖质量[41]。最终,通过光照、温度、pH和渗透压等因子的阶段化梯度调控,可系统提升高质量木本植物再生。

-

自然条件下植物遭受创伤或胁迫后可通过去分化和再分化重建组织与器官,维持个体完整性[42]。在组织培养中,植物再生主要通过器官发生与体细胞胚胎发生2条途径实现。器官发生途径中,外植体在植物生长调节剂调控下依次经历愈伤形成、器官原基决定根芽建成,最终形成完整植株[43]。中国在杨树Populus spp.、柑橘、茶树Camellia sinensis等木本植物上已建立了较成熟的研究体系[44−46]。相较于体细胞胚胎发生,器官发生在大多数木本植物中的应用更广泛,且培养过程更易于控制,其中生长素和细胞分裂素的时空分布模式,共同决定细胞是发育成根还是芽[3, 14]。

-

愈伤组织是植物产生无组织的细胞团,具有全能性[47]。在拟南芥中,此过程遵循“侧根发育程序再激活”的保守路径,主要起源于中柱鞘细胞,通过转录组分析证实,这些愈伤组织具有与根分生组织高度相似的基因表达谱[48−50]。依赖于PIN-FORMED (PIN)家族蛋白(如PIN1)介导的生长素极性运输建立信号最大值,并由此激活LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN (LBD) 家族的核心转录因子(如LBD16/17/18/29)等,驱动细胞重编程[50−51]。然而,木本植物愈伤组织的形成与质量常受到其多年生特性的严重制约。成年态木本植物细胞中存在稳定的表观遗传屏障(如高水平的H3K27me3和DNA甲基化),这些修饰沉默了下游再生相关基因(如LBD、WOX),尤为重要的是,木本植物的表观遗传状态常呈现季节性动态变化,其DNA甲基化水平等印记直接决定了取材的“可再生性窗口”——通常仅在生长旺盛期(如春季)取材的外植体具有最佳再生能力[52−54]。上述这些机制共同构成了其再生潜力随年龄增长而衰退(即成熟效应)的核心分子机制,此外,强烈的基因型依赖性和内源酚类物质氧化进一步加剧了再生困难[55−56]。

-

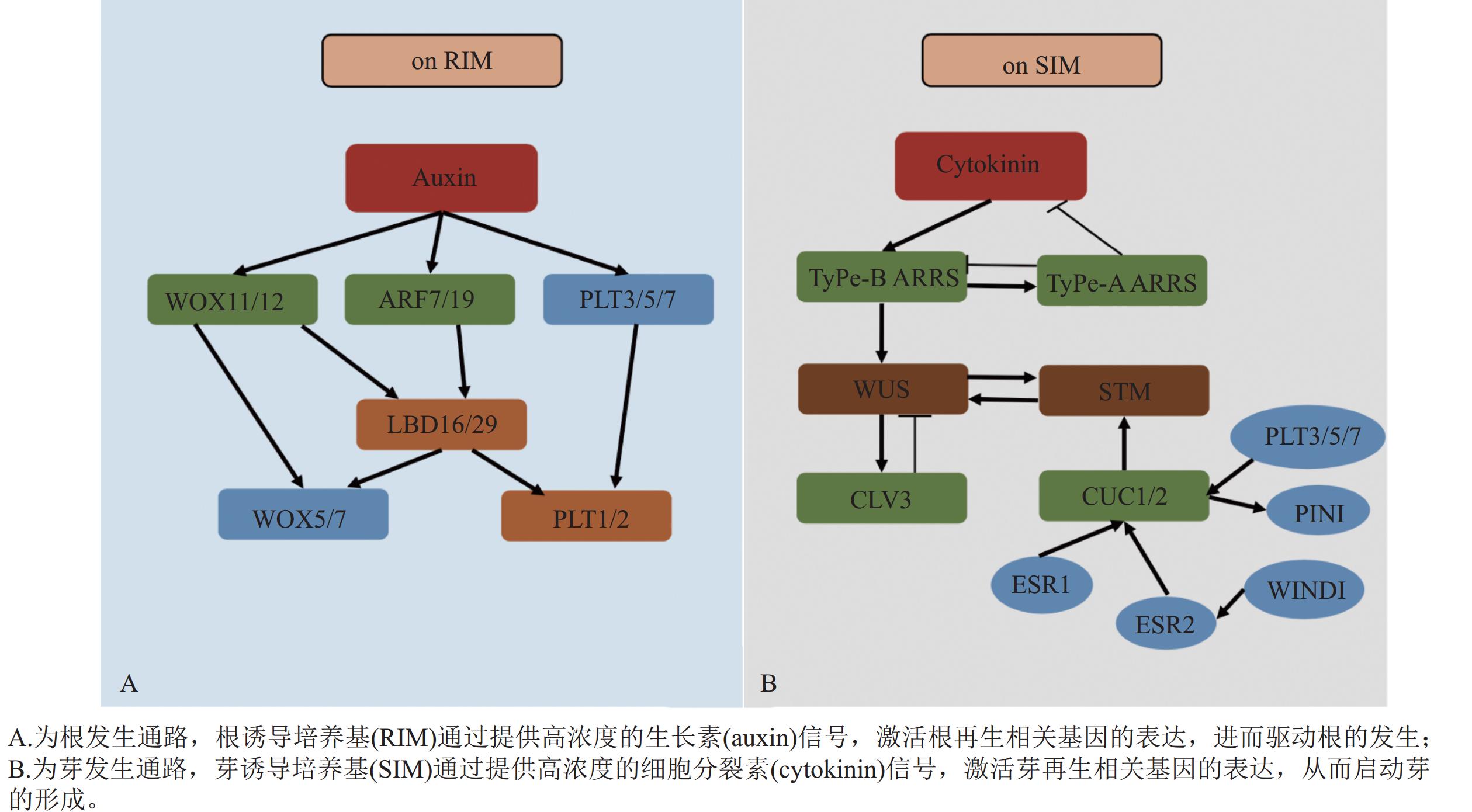

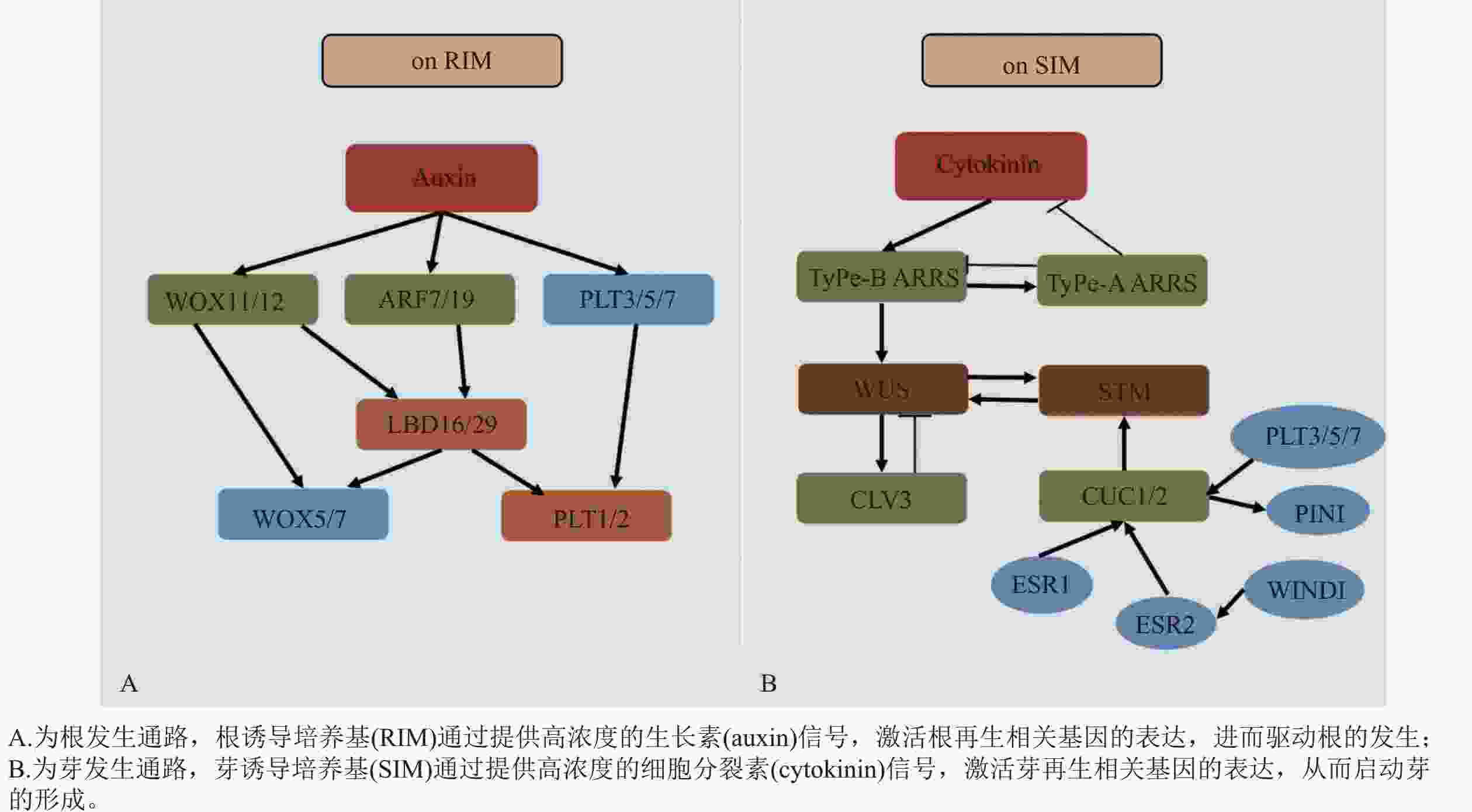

木本植物不定根多起源于茎、叶等非中柱鞘来源组织,其发生依赖于外源生长素对根原基的诱导。生长素信号通路的核心调控,其中WOX11的功能尤为关键,在杨树中,CRISPR/Cas9介导的PtoWOX11基因敲除显著抑制了不定根的形成,而其过表达则能促进根原基发生[11, 57]。生长素响应因子(AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR, ARF)与生长素响应元件(AuxREs)结合激活WOX11/12,进一步诱导WOX5/7、LBD16/29与PLETHORA(PLT1/2)等基因表达,共同促进创始细胞分裂与根原基建立(图1A)[3, 58−59]。木本植物不定根发生的最大挑战在于成年态障碍。成年材料中累积的表观遗传印记(如PLT基因的H3K27me3修饰)及休眠相关基因(如DORMANCY-ASSOCIATED MADS-box, DAM)的表达显著抑制生根能力[9, 60]。此外,该调控通路表现出显著的物种特异性,例如WOX11在易生根的杨树中被证实为核心因子[11, 57]。然而,在松树这种难生根物种中,WOX5的持续表达可能至关重要[56]。这种物种间再生能力的差异,部分源于木本植物在长期进化中经历的基因家族扩张与功能分化,也凸显了在不同树种中开展基因功能直接验证的重要性与迫切性。

-

不定芽诱导以细胞分裂素信号为主导,其关键在于茎端分生组织与干细胞稳态的重建。细胞分裂素通过其信号转导元件——b型响应调节因子(b-ARRs如ARR1/2/10/12)促进WUS表达,同时,b-ARRs也会诱导a-ARRs表达,后者作为负反馈因子拮抗细胞分裂素信号,从而精细调控这一过程[61]。WUS蛋白随后迁移至干细胞区诱导CLAVATA3 (CLV3),CLV3蛋白作为一种信号肽,反向扩散至组织中心抑制WUS的表达,由此构成一个经典的负反馈环路,动态维持干细胞池的稳定。另一方面,CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC1/2)上调SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM),PLT3/5/7、ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION (ESR1/2)、WOUND INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION 1 (WIND1)和PIN1进一步激活CUC-STM模块,推动芽原基形成[3, 61−64]。WUS与STM还能直接互作并共同激活CLV3,显示2条通路在茎端分生组织稳态处汇合(图1B)。该通路的重建效率受基因型差异(如ARR12等位变异)和表观屏障(如WUS启动子超甲基化)的显著影响,这种基因型依赖性在木本植物中尤为突出,例如杨树‘84K’Populus alba × P. glandulosa ‘84K’,因对细胞分裂素响应高效而被广泛用作高再生基因型模型,可通过去甲基化剂(如5-氮杂胞苷)预处理或筛选此类高响应基因型等策略来优化再生体系[65]。

-

木本植物的器官发生是一个由信号触发、激素梯度塑形、干细胞网络重建到器官命运执行的连续而精密的过程[61]。其中,根发育主要依赖生长素-ARF-WOX11/12-LBD/PLT-WOX5信号通路,芽发育则依赖于细胞分裂素-b-ARRs-WUS-CLV3及STM-CUC通路,这些通路通过WUS/STM-CLV3节点相互协调,共同调控器官发生的位置与稳定性[3, 14]。

基于该机制,研究时可从以下关键参数入手优化培养体系:①生长素峰值出现时间与运输蛋白的活性,直接影响器官发生的位置与质量;②细胞分裂素的浓度与处理时间,显著影响茎端分生组织形成效率;③H3K27me3等表观修饰状态,影响细胞再生能力。为提高实验可重复性,应在方法中明确记录各阶段激素使用的浓度与时间、培养基关键参数,并可结合组学数据识别再生过程中的限制环节[16, 66−68]。

-

成年木本植物普遍出现再生能力衰退现象,具体表现为诱导周期长、根系发育差与移栽成活率低。以杨树为例,成年树的茎段或叶片外植体通常要比幼嫩材料更难生根,且根系发育迟缓[69]。该现象与内源激素响应能力减弱、表观遗传抑制加深以及酚类物质积累干扰生长素极性运输密切相关[52, 70−71]。

针对上述问题,可采取生理与表观遗传协同调控的综合方案。在生理层面,通过短时间、高浓度的IBA强烈刺激,打破成年材料细胞的休眠状态,建立起启动生根所必需的初始信号,随后,转换至低强度生长素(如NAA)或无激素培养基中进行根培养,避免持续胁迫及酚类物质对运输的干扰。根据不同木本植物的需求差异,培养方案也不同,如观赏花木侧重温和培养以提升成苗一致性,而经济林则追求强诱导策略以实现快速生根与高移栽成活率。同时,结合低盐培养基(如½MS或WPM)及抗氧化剂(如AsA、PVP),可减轻氧化损伤,为根原基发生创造低胁迫微环境[16, 23, 52]。在表观遗传层面,可靶向清除再生基因抑制标记的策略,如利用CRISPR/dCas9介导的靶向去甲基化技术,特异性激活WOX11或PLT等基因,从而从根本上改善成年材料的生根潜力,而非仅仅依赖外源激素的强制启动[54, 71−72]。例如杂交落羽杉Taxodiomeria peizhongii ‘Zhongshanshan ’体细胞胚胎发生中,5-氮杂胞苷(5-AzaC)在诱导去甲基化的同时增强抗氧化酶活性,系统改善氧化还原稳态,从而显著提高体胚产量[71]。

-

褐化受材料内因(基因型、器官部位、成熟度)与培养外因(盐浓度、碳源、植物生长调节剂配比、灭菌/消毒方式)共同影响,其核心机制是创伤胁迫激活多酚氧化酶(PPO),催化酚类物质氧化为有毒的醌类物质,导致外植体褐化死亡[73−74]。

因此,防止褐化需建立针对性的综合策略,常规方法包括优化灭菌方式、采用低盐培养基、添加抗氧化剂和吸附剂,以减轻氧化胁迫。根本性解决褐化瓶颈,则要解析品种特异的酚类代谢网络,通过多组学技术鉴定导致褐化的关键基因,从而开发基因编辑手段(如CRISPR-Cas9靶向敲除)或设计小分子抑制剂,在源头上阻止有害醌类物质的产生[16, 23, 73]。例如在牡丹Paeonia suffruticosa中,特定的酚酸谱与根促生长特性密切相关,这表明通过培养条件(如光质、温度)或添加剂(如稀土元素、水杨酸)适度调控酚代谢流向,可能更有助于改善器官发生与再生品质[75]。

-

木本植物的器官发生存在显著基因型依赖性。不同基因型在细胞重编程能力、激素响应和表观状态等方面存在显著差异,阻碍通用再生体系的建立[76−78]。例如在樱属Prunus植物(如P. yedoensis)的器官发生研究中,培养基选择与植物生长调节剂处理时序对不同基因型的成苗率、畸形率具有显著影响,需要对品种进行系统优化[79]。

短期策略是通过表型快速筛选,为不同基因型确定最优的“培养基-植物生长调节剂”组合[80−81];长远策略则可以利用多组学技术绘制再生能力图谱,识别其特有的障碍基因或沉默标记[82]。在此基础上,开发个性化的预培养方案或添加特异的信号分子及表观调控剂,协同调控内源再生通路,从而推动木本植物再生技术从依赖经验向基于分子机制的系统性研究。

-

建立高效的木本植物器官发生体系,关键在于实现外源培养条件(外植体、培养基、植物生长调节剂、环境)与内源分子网络(激素信号、转录因子、表观遗传)的协同互作。同时梳理了从愈伤诱导到器官建成的核心通路:不定芽发生依赖细胞分裂素-WUS-CLV3与STM-CUC调控模块,而不定根发生则由生长素-ARF-WOX-LBD信号轴主导。

尽管研究已取得显著进展,但成年材料再生障碍、酚类褐化、强基因型依赖性等仍是当前面临的主要挑战。因此,建议在方法中明确培养参数,如盐强度、糖浓度、铁源类型、PGR配比与时序,并结合多组学技术与关键突变体材料,解析再生能力的遗传与表观遗传基础。未来研究应着重以下方向:①利用多组学技术(如单细胞转录组、表观基因组学)绘制不同基因型木本植物的再生基因调控网络,鉴定再生的关键限制环节和主效调控因子,为特定难再生树种或品种开发定制化策略。②开发基于CRISPR/dCas9的表观基因组编辑技术,定向调控WOX、WUS等关键基因的染色质状态;③将再生体系与遗传转化技术深度融合,建立基因型无关的遗传改良平台。通过机制解析与技术创新的双轮驱动,有望突破木本植物再生中的瓶颈,为林木育种与基因功能研究提供有力支撑。

Research progress on organogenic regeneration in woody plants based on tissue culture

-

摘要: 木本植物的高效遗传转化与无性繁殖是实现其遗传改良与产业化的核心环节,然而当前器官发生型再生体系在成年材料中普遍存在生根困难、褐化严重及强基因型依赖性等技术瓶颈,严重制约了相关育种与繁育进程。本研究系统梳理了影响再生效率的关键外部因素,包括外植体选择、培养基优化以及植物生长调节剂的配比与处理时序。在分子机制层面,重点阐述了从愈伤诱导到不定根/不定芽形成过程中的细胞与分子调控机制,揭示了生长素信号(ARF-WOX-LBD通路)调控不定根发生以及细胞分裂素信号(ARR-WUS-CLV3环路)调控不定芽建成的核心机制。针对成年材料生根困难和高酚品种褐化严重等技术瓶颈,提出了结合生理与表观遗传调控的综合对策。本研究分析指出:木本植物器官发生能力受外部培养条件、内部激素通路与表观遗传状态的共同调控,成年材料再生障碍的本质在于再生相关基因在表观层面被系统性抑制。未来通过深化机制解析与技术创新,将有望系统突破木本植物再生障碍,为林木精准育种与基因功能研究提供体系支撑。图1表2参82Abstract: However, the current organogenic regeneration system generally has technical bottlenecks such as rooting difficulties, severe browning and strong genotype dependence in adult materials, which seriously restricts the relevant breeding and breeding process. The key external factors affecting regeneration efficiency, including explant selection, media optimization, and the ratio and treatment timing of plant growth regulators (PGRs) are systematically sorted out. At the molecular mechanism level, the cellular and molecular regulatory mechanisms from callus induction to adventitious root/adventitious bud formation were expounded, and the core mechanisms of auxin signaling (ARF-WOX-LBD pathway) regulating adventitious root genesis and cytokinin signaling (ARR-WUS-CLV3 loop) regulating adventitious bud formation were revealed. In view of the technical bottlenecks such as the difficulty of rooting of adult materials and the serious browning of high-phenolic varieties, a comprehensive countermeasure combining physiological and epigenetic regulation was further proposed. This paper analyzes that the organogenesis of woody plants is jointly regulated by external culture conditions, internal hormone pathways and epigenetic status, and the essence of adult material regeneration disorder is that regeneration-related genes are systematically inhibited at the epigenetic level. In the future, through deepening mechanism analysis and technological innovation, it is expected to systematically break through the regrowth obstacles of woody plants and provide systematic support for precision breeding and gene function research of forest trees. [Ch, 1 fig. 2 tab. 82 ref.]

-

Key words:

- woody plants /

- organogenesis /

- tissue culture /

- plant growth regulators /

- epigenetics /

- adventitious root /

- adventitious shoot

-

表 1 不同外植体与培养体系的关键参数及结果

Table 1. Key parameters and outcomes across different explant and culture systems

物种 外植体 培养基 植物生长调节剂组合

(诱导/分化)温度/℃ 光强/lx 诱导率/% 异常率/% 文献 银杉Cathaya argyrophylla 成熟胚 DCR/½MS 0.5 6-BA/0.2 NAA+0.5 IBA 25±2 2000 ~3000 >60 <30 (未发育率) [19] 高山杜鹃Rhododendron

chrysanthum叶片 WPM/WPM 0.5~1.5 TDZ+0.5 NAA/

0.5 IBA+1.0~1.5 NAA24±2 1500 ~1800 100 0 (褐化率) [20] 牡丹Paeonia suffruticosa 花丝 MSB/½WPN 0.5 2,4-D+0.25 TDZ/1.0 IBA+

0.1 NAA+1.0 VB2+1.0 腐胺25±1 >90 <10 (褐化率) [21] 胡桃楸Juglans mandshurica 腋芽茎段 WPM/½MS 2.0 6-BA+0.01 IBA/1.0 IBA 25±2 2 000 80 20 (褐化率) [22] 说明:植物生长调节剂前的数值单位为mg·L−1。 表 2 常用培养基关键参数对比(木本器官发生导向)

Table 2. Comparison of key parameters of commonly used culture media (woody organogenesis orientation)

培养基 总盐强度

(相对MS)${\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}/{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-} $ 微量元素(铁源) 推荐阶段 注意事项 具体案例 MS 1.0 高铵 Fe-EDTA 通用 高铵易导致褐化,

慎用全强度培养基茶树Camellia sinensis茎段[29]

不定芽诱导、增殖½MS/

改良MS0.5~0.8 中/低铵 Fe-EDTA/

Fe-EDDHA芽分化和伸长阶段;

生根培养降盐降糖减轻玻璃化;

适合对铵敏感木本植物银白杨Populus alba腋芽茎段[30]

不定芽生根WPM 0.6~0.7 低铵 微量元素优化;

Fe-EDTA促进枝条和根系生长 木本优选,

降低褐化、玻璃化胡桃楸Juglans mandshuriea腋芽

茎段[22]不定芽诱导DKW ≈0.8 中铵 ${\mathrm{SO}}_{4}^{2-} $较高;

Fe-EDTA生根;体细胞胚胎发生 与TDZ或IBA协同使用

效果更佳核桃Juglans regia带芽茎段[31]

不定芽诱导说明:“总盐强度”数值是以MS培养基的总离子浓度为基准(1.0)的无量纲相对比值,用于直观比较不同培养基的宏观渗透压与营养负荷。 -

[1] GEORGE E F, HALL M A, DE KLERK G J. Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture Vol 1: the Background [M]. 3rd ed. Dordrecht: Springer, 2008: 65−175. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5005-3. [2] THORPE T A. History of plant tissue culture [J]. Molecular Biotechnology, 2007, 37(2): 169−180. DOI: 10.1007/s12033-007-0031-3. [3] LONG Yun, YANG Yun, PAN Guangtang, et al. New insights into tissue culture plant-regeneration mechanisms[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022, 13: 926752. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2022.926752. [4] VASIL I K. A history of plant biotechnology: from the Cell Theory of Schleiden and Schwann to biotech crops [J]. Plant Cell Reports, 2008, 27(9): 1423−1440. DOI: 10.1007/s00299-008-0571-4. [5] HILL K, SCHALLER G E. Enhancing plant regeneration in tissue culture: a molecular approach through manipulation of cytokinin sensitivity[J]. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2013, 8(10): 25709. DOI: 10.4161/psb.25709. [6] XU Lin, HUANG Hai. Genetic and epigenetic controls of plant regeneration [J]. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, 2014, 108: 1−33. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391498-9.00009-7. [7] SANG Yalin, CHENG Zhijuan, ZHANG Xiansheng. Plant stem cells and de novo organogenesis [J]. The New Phytologist, 2018, 218(4): 1334−1339. DOI: 10.1111/nph.15106. [8] GUAN Yuan, LI Shuigen, FAN Xiaofen, et al. Application of somatic embryogenesis in woody plants[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 938. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00938. [9] MÉNDEZ-HERNÁNDEZ H A, LEDEZMA-RODRÍGUEZ M, AVILEZ-MONTALVO R N, et al. Signaling overview of plant somatic embryogenesis[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2019, 10: 77. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00077. [10] KHAN F S, ZENG Renfang, GAN Zhimeng, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the WOX gene family in Citrus sinensis and functional analysis of a CsWUS member[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(9): 4919. DOI: 10.3390/ijms22094919. [11] LI Jianbo, ZHANG Jin, JIA Huixia, et al. The WUSCHEL-related homeobox 5a (PtoWOX5a) is involved in adventitious root development in poplar [J]. Tree Physiology, 2018, 38(1): 139−153. DOI: 10.1093/treephys/tpx118. [12] ZHOU Xiaoqi, HAN Haitao, CHEN Jinhui, et al. The emerging roles of WOX genes in development and stress responses in woody plants[J]. Plant Science, 2024, 349: 112259. DOI: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112259. [13] RYMEN B, KAWAMURA A, LAMBOLEZ A, et al. Histone acetylation orchestrates wound-induced transcriptional activation and cellular reprogramming in Arabidopsis[J]. Communications Biology, 2019, 2: 404. DOI: 10.1038/s42003-019-0646-5. [14] LEE S, PARK Y S, RHEE J H, et al. Insights into plant regeneration: cellular pathways and DNA methylation dynamics[J]. Plant Cell Reports, 2024, 43(5): 120. DOI: 10.1007/s00299-024-03216-9. [15] PARK Y S, BONGA J M, MOON H K. Vegetative Propagation of Forest Trees[C]. Seoul: National Institute of Forest Science (NiFos), 2016: 302−322. [16] AHMAD I, HUSSAIN T, ASHRAF I, et al. Lethal effects of secondary metabolites on plant tissue culture [J]. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, 2013, 13(4): 539−547. [17] PRAKASH M G, GURUMURTHI K. Effects of type of explant and age, plant growth regulators and medium strength on somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Eucalyptus camaldulensis [J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 2010, 100(1): 13−20. DOI: 10.1007/s11240-009-9611-1. [18] OTIENDE M A, FRICKE K, NYABUNDI J O, et al. Involvement of the auxin–cytokinin homeostasis in adventitious root formation of rose cuttings as affected by their nodal position in the stock plant[J]. Planta, 2021, 254(4): 65. DOI: 10.1007/s00425-021-03709-x. [19] 买凯乐, 李荣珍, 刘宏, 等. 银杉愈伤组织诱导植株再生的影响因素[J]. 林业科学, 2024, 60(7): 56−64. MAI Kaile, LI Rongzhen, LIU Hong, et al. Factors influencing the callus induction and plant regeneration of Cathaya argyrophylla [J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2024, 60(7): 56−64. [20] 南雅琪, 刘娟, 齐宇, 等. 高山杜鹃组培快繁关键技术研究[J]. 安徽农业科学, 2024, 52(22): 42−46. NAN Yaqi, LIU Juan, QI Yu, et al. Research on key techniques for tissue culture of Rhododendron lapponicum [J]. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 2024, 52(22): 42−46. [21] 王娜. 不同牡丹品种再生体系技术研究[D]. 洛阳: 河南科技大学, 2024. WANG Na. Study on Regeneration Aystem Technology of Different Peony Varieties[D]. Luoyang: Henan University of Science and Technology, 2024. [22] 范新蕊. 胡桃楸组织培养技术的研究[D]. 沈阳: 沈阳农业大学, 2023. FAN Xinrui. Study on Tissue Culture Technology of Juglans mandshurica Maxim[D]. Shenyang: Shenyang Agricultural University, 2023. [23] PHILLIPS G C, GARDA M. Plant tissue culture media and practices: an overview [J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 2019, 55(3): 242−257. [24] GAGO D, SÁNCHEZ C, ALDREY A, et al. Micropropagation of plum (Prunus domestica L.) in bioreactors using photomixotrophic and photoautotrophic conditions [J]. Horticulturae, 2022, 8(4): 286. DOI: 10.3390/horticulturae8040286. [25] GAO Yue, WANG Qinmei, AN Qinxia, et al. A novel micropropagation of Lycium ruthenicum and epigenetic fidelity assessment of three types of micropropagated plants in vitro and ex vitro[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(2): e0247666. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247666. [26] 陈铭秋, 刘果, 林彦, 等. 木本植物组织培养及器官从头再生的研究进展[J]. 桉树科技, 2023, 40(4): 85−96. CHEN Mingqiu, LIU Guo, LIN Yan, et al. Research progress in tissue culture and organ de novo regeneration of woody plants [J]. Eucalypt Science & Technology, 2023, 40(4): 85−96. [27] LICEA-MORENO R J, CONTRERAS A, MORALES A V, et al. Improved walnut mass micropropagation through the combined use of phloroglucinol and FeEDDHA [J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 2015, 123(1): 143−154. DOI: 10.1007/s11240-015-0822-3. [28] PASTERNAK T P, STEINMACHER D. Plant growth regulation in cell and tissue culture in vitro[J]. Plants, 2024, 13(2): 327. [29] 章文益. 茶树茎段再生体系的建立[D]. 贵阳: 贵州大学, 2022. ZHANG Wenyi. Establishment of a Regeneration System from Stem Segments in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis)[D]. Guiyang: Guizhou University, 2022. [30] 沈霞, 杨小林, 马和平, 等. 银白杨组织培养生根条件影响因子研究[J]. 西部林业科学, 2020, 49(4): 48−53. SHEN Xia, YANG Xiaolin, MA Heping, et al. Rooting influencing factors of Populus alba tissue culture [J]. Journal of West China Forestry Science, 2020, 49(4): 48−53. [31] 张新超, 张新宇, 张雪梅, 等. ‘绿岭’核桃带芽茎段的组织培养和快速繁殖[J]. 北方园艺, 2023(24): 38−44. ZHANG Xinchao, ZHANG Xinyu, ZHANG Xuemei, et al. Tissue culture and rapid propagation of ‘lyuling’ walnut stems with axillary buds [J]. Northern Horticulture, 2023(24): 38−44. [32] de OLIVEIRA L S, BRONDANI G E, MOLINARI L V, et al. Optimal cytokinin/auxin balance for indirect shoot organogenesis of Eucalyptus cloeziana and production of ex vitro rooted micro-cuttings [J]. Journal of Forestry Research, 2022, 33(5): 1573−1584. DOI: 10.1007/s11676-022-01454-9. [33] KIM S H, ZEBRO M, JANG D C, et al. Optimization of plant growth regulators for in vitro mass propagation of a disease-free ‘Shine Muscat’ grapevine cultivar [J]. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 2023, 45(10): 7721−7733. DOI: 10.3390/cimb45100487. [34] del CARMEN OROZCO-MOSQUEDA M, SANTOYO G, GLICK B R. Recent advances in the bacterial phytohormone modulation of plant growth[J]. Plants, 2023, 12(3): 606. DOI: 10.3390/plants12030606. [35] WU Qinggui, YANG Honglin, SUN Yuxi, et al. Organogenesis and high-frequency plant regeneration in Caryopteris terniflora Maxim. using thidiazuron [J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant, 2021, 57(1): 39−47. [36] TALLÓN C I, PORRAS I, PÉREZ-TORNERO O. Efficient propagation and rooting of three Citrus rootstocks using different plant growth regulators [J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 2012, 48(5): 488−499. [37] JYOTI J. Micropropagation of Hazelnut (Corylus Species) [D]. Guelph: University of Guelph, 2013. [38] DÍAZ-RUEDA P, CANTOS-BARRAGÁN M, COLMENERO-FLORES J M. Growth quality and development of olive plants cultured in-vitro under different illumination regimes[J]. Plants, 2021, 10(10): 2214. DOI: 10.3390/plants10102214. [39] 王娜, 杨柳, 赵国栋, 等. 重要木本植物组织培养技术研究进展[J]. 上海农业学报, 2025, 41(1): 131−142. WANG Na, YANG Liu, ZHAO Guodong, et al. Advances in tissue culture techniques of important woody plants [J]. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai, 2025, 41(1): 131−142. [40] 沈霞. 银白杨幼化与环境因子响应[D]. 拉萨: 西藏大学, 2020. SHEN Xia. Silver Poplar Incubation and Environmental Factor Response[D]. Lhasa: Tibet University, 2020. [41] 于秋莹, 郭苗苗, 许岢昕, 等. 欧洲丁香品种‘Downfield’花序和花序轴愈伤组织诱导和悬浮培养[J]. 东北林业大学学报, 2023, 51(3): 47−53. YU Qiuying, GUO Miaomiao, XU Kexin, et al. Callus induction and suspension culture with inflorescence and inflorescence axis of Syringa vulgaris ‘Downfield’ [J]. Journal of Northeast Forestry University, 2023, 51(3): 47−53. [42] IKEUCHI M, OGAWA Y, IWASE A, et al. Plant regeneration: cellular origins and molecular mechanisms [J]. Development, 2016, 143(9): 1442−1451. DOI: 10.1242/dev.134668. [43] SUGIMOTO K, JIAO Yuling, MEYEROWITZ E M. Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway [J]. Developmental Cell, 2010, 18(3): 463−471. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.004. [44] PETERNEL Š, GABROVŠEK K, GOGALA N, et al. In vitro propagation of European aspen (Populus tremula L. ) from axillary buds via organogenesis[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2009, 121(1): 109−112. [45] TALLÓN C I, PORRAS I, PÉREZ-TORNERO O. High efficiency in vitro organogenesis from mature tissue explants of Citrus macrophylla and C. aurantium [J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 2013, 49(2): 145−155. [46] BORCHETIA S, DAS S C, HANDIQUE P J, et al. High multiplication frequency and genetic stability for commercialization of the three varieties of micropropagated tea plants (Camellia spp. ) [J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2009, 120(4): 544−550. DOI: 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.12.007. [47] IKEUCHI M, SUGIMOTO K, IWASE A. Plant callus: mechanisms of induction and repression [J]. The Plant Cell, 2013, 25(9): 3159−3173. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.113.116053. [48] ATTA R, LAURENS L, BOUCHERON-DUBUISSON E, et al. Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro [J]. The Plant Journal, 2009, 57(4): 626−644. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03715.x. [49] CHE Ping, LALL S, HOWELL S H. Developmental steps in acquiring competence for shoot development in Arabidopsis tissue culture [J]. Planta, 2007, 226(5): 1183−1194. DOI: 10.1007/s00425-007-0565-4. [50] FAN Mingzhu, XU Chongyi, XU Ke, et al. Lateral organ boundaries domain transcription factors direct callus formation in Arabidopsis regeneration [J]. Cell Research, 2012, 22(7): 1169−1180. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2012.63. [51] XU Chongyi, CAO Huifen, ZHANG Qianqian, et al. Control of auxin-induced callus formation by bZIP59-LBD complex in Arabidopsis regeneration [J]. Nature Plants, 2018, 4(2): 108−115. DOI: 10.1038/s41477-017-0095-4. [52] AMARAL J, RIBEYRE Z, VIGNEAUD J, et al. Advances and promises of epigenetics for forest trees[J]. Forests, 2020, 11(9): 976. DOI: 10.3390/f11090976. [53] LIU Xuemei, ZHU Kehui, XIAO Jun. Recent advances in understanding of the epigenetic regulation of plant regeneration [J]. aBIOTECH, 2023, 4(1): 31−46. DOI: 10.1007/s42994-022-00093-2. [54] LI Jiawen, ZHANG Qiyan, WANG Zejia, et al. The roles of epigenetic regulators in plant regeneration: exploring patterns amidst complex conditions [J]. Plant Physiology, 2024, 194(4): 2022−2038. DOI: 10.1093/plphys/kiae042. [55] OZYIGIT I I. Phenolic changes during in vitro organogenesis of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. ) shoot tips [J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2008, 7: 1145−1150. [56] BUENO N, CUESTA C, CENTENO M L, et al. In vitro plant regeneration in conifers: the role of WOX and KNOX gene families[J]. Genes, 2021, 12(3): 438. DOI: 10.3390/genes12030438. [57] XU Meng, XIE Wenfan, HUANG Minren. Two WUSCHEL-related HOMEOBOX genes, PeWOX11a and PeWOX11b, are involved in adventitious root formation of poplar [J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2015, 155(4): 446−456. DOI: 10.1111/ppl.12349. [58] XU Chongyi, HU Yuxin. The molecular regulation of cell pluripotency in plants [J]. aBIOTECH, 2020, 1(3): 169−177. DOI: 10.1007/s42994-020-00028-9. [59] WAN Qihui, ZHAI Ning, XIE Dixiang, et al. WOX11: the founder of plant organ regeneration[J]. Cell Regeneration, 2023, 12(1): 1. DOI: 10.1186/s13619-022-00140-9. [60] CHEN Zhaoyu, CHEN Yadi, SHI Lanxi, et al. Interaction of phytohormones and external environmental factors in the regulation of the bud dormancy in woody plants[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(24): 17200. DOI: 10.3390/ijms242417200. [61] SUGIMOTO K, TEMMAN H, KADOKURA S, et al. To regenerate or not to regenerate: factors that drive plant regeneration [J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2019, 47: 138−150. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.12.002. [62] SU Ying hua, ZHOU Chao, LI Ying ju, et al. Integration of pluripotency pathways regulates stem cell maintenance in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020, 117(36): 22561−22571. [63] ZHANG Tianqi, LIAN Heng, ZHOU Chuanmiao, et al. A two-step model for de novo activation of WUSCHEL during plant shoot regeneration [J]. The Plant Cell, 2017, 29(5): 1073−1087. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.16.00863. [64] HAN Han, LIU Xing, ZHOU Yun. Transcriptional circuits in control of shoot stem cell homeostasis [J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2020, 53: 50−56. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbi.2019.10.004. [65] WEN Shuangshuang, GE Xiaolan, WANG Rui, et al. An efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method for hybrid poplar 84K (Populus alba × P. glandulosa) using calli as explants[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022, 23(4): 2216. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23042216. [66] HAN H, SUN X M, XIE Y H, et al. Anatomical and physiological effects of phytohormones on adventitious roots development in Larix kaempferi × L. olgensis [J]. Silvae Genetica, 2013, 62(1/6): 96−103. DOI: 10.1515/sg-2013-0012. [67] Da COSTA C T, OFFRINGA R, FETT-NETO A G. The role of auxin transporters and receptors in adventitious rooting of Arabidopsis thaliana pre-etiolated flooded seedlings[J]. Plant Science, 2020, 290: 110294. DOI: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110294. [68] DRUEGE U, HILO A, PÉREZ-PÉREZ J M, et al. Molecular and physiological control of adventitious rooting in cuttings: phytohormone action meets resource allocation [J]. Annals of Botany, 2019, 123(6): 929−949. DOI: 10.1093/aob/mcy234. [69] BANNOUD F, BELLINI C. Adventitious rooting in Populus species: update and perspectives[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2021, 12: 668837. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2021.668837. [70] BATALOVA A Y, KRUTOVSKY K V. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of longevity in forest trees[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(12): 10403. DOI: 10.3390/ijms241210403. [71] YUAN Guoying, WANG Dan, YU Chaoguang, et al. 5-AzaCytidine promotes somatic embryogenesis of Taxodium hybrid ‘Zhongshanshan’ by regulating redox homeostasis[J]. Plants, 2025, 14(9): 1354. DOI: 10.3390/plants14091354. [72] YAN An, BORG M, BERGER F, et al. The atypical histone variant H3.15 promotes callus formation in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Development, 2020, 147(11): dev184895. DOI: 10.1242/dev.184895. [73] ABDALLA N, EL-RAMADY H, SELIEM M K, et al. An academic and technical overview on plant micropropagation challenges[J]. Horticulturae, 2022, 8(8): 677. DOI: 10.3390/horticulturae8080677. [74] POURCEL L, ROUTABOUL J M, CHEYNIER V, et al. Flavonoid oxidation in plants: from biochemical properties to physiological functions [J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2007, 12(1): 29−36. DOI: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.006. [75] SHANG Wenqian, WANG Zheng, HE Songlin, et al. Research on the relationship between phenolic acids and rooting of tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa) plantlets in vitro [J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2017, 224: 53−60. DOI: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.04.038. [76] MA C, GODDARD A, PEREMYSLOVA E, et al. Factors affecting in vitro regeneration in the model tree Populus trichocarpa I. Medium, environment, and hormone controls on organogenesis [J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 2022, 58(6): 837−852. [77] SHARMA V, ANKITA, KARNWAL A, et al. A comprehensive review uncovering the challenges and advancements in the in vitro propagation of Eucalyptus plantations[J]. Plants, 2023, 12(17): 3018. DOI: 10.3390/plants12173018. [78] VALL-LLAURA N, TORRES R, TEIXIDÓ N, et al. Untangling the role of ethylene beyond fruit development and ripening: a physiological and molecular perspective focused on the Monilinia-peach interaction[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2022, 301: 111123. DOI: 10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111123. [79] CHEONG E J. Organogenesis from callus derived from in vitro root tissues of wild Prunus yedoensis Matsumura [J]. Journal of Forest and Environmental Science, 2019, 35(1): 41−46. [80] GAILIS A, SAMSONE I, ŠĒNHOFA S, et al. Silver birch (Betula pendula Roth. ) culture initiation in vitro and genotype determined differences in micropropagation [J]. New Forests, 2021, 52(5): 791−806. DOI: 10.1007/s11056-020-09828-9. [81] VAHDATI K, SADEGHI-MAJD R, SESTRAS A F, et al. Clonal propagation of walnuts (Juglans spp. ): a review on evolution from traditional techniques to application of biotechnology[J]. Plants, 2022, 11(22): 3040. DOI: 10.3390/plants11223040. [82] YANG Jie, GU Dachuan, WU Shuhua, et al. Feasible strategies for studying the involvement of DNA methylation and histone acetylation in the stress-induced formation of quality-related metabolites in tea (Camellia sinensis)[J]. Horticulture Research, 2021, 8: 253. DOI: 10.1038/s41438-021-00679-9. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250455

下载:

下载: