-

木材是一种多孔性、层次状、各向异性的非均质天然高分子复合材料,主要由纤维素、半纤维素和木质素3种高分子聚合物组成。木材的实体物质为其细胞壁,细胞壁中的纤维素通过分子链聚集成排列有序的微纤丝束,构成了细胞壁的基本骨架[1]。揭示木材细胞壁特别是其骨架的超微构造的形成及变化规律,对木材细胞壁的改性处理以及后续的遗传改良等具有重要的科学意义。木材细胞壁在超微水平上主要以纤维素微纤丝及结晶区的形式体现,木材科学中常用微纤丝角表征细胞次生壁S2层中微纤丝排列方向与细胞主轴方向的夹角,用结晶度和微晶形态表征结晶区和其基本组成结构的大小[1]。木材细胞壁超微构造即微纤丝和结晶区的研究是木材科学领域的研究热点之一[2]。近年来关于细胞壁超微构造形成的研究较多,如葡萄糖形成纤维素单链,继而形成微晶、微纤丝和结晶区等过程[3];射线技术、尖端显微镜以及光谱类仪器在木材超微结构表征中的应用[4],进一步揭示了微纤丝和结晶区的结构特征。研究发现微纤丝角和结晶度沿轴向和径向的变化规律不尽相同,对细胞形态的影响也不同[5-6],但对细胞壁微晶形态及变化特点方面的研究还不够深入;细胞壁超微构造会影响木材密度、干缩性和强度等物理力学性能[7-8],而探究微纤丝角、结晶度和微晶形态的形成及变化规律,是了解木材的基础性质的重要途径之一。以往对木材细胞壁超微构造的研究多集中于某一超微构造或某种表征方法方面,对不同种类木材及同种木材不同生长部位细胞壁纤维素微纤丝及结晶区的形成和变化及其表征方法未见系统报导。笔者详述了木材细胞壁微纤丝和结晶区的形成、表征方法、变化规律及其对细胞形态的影响,以期为今后木材的超微构造的深入研究和为基于细胞壁微纤丝和微晶结构特征来预测木材基础性质、早期良种选育以及材料的高效利用等方面提供详细的科学资料。

HTML

-

微晶、微纤丝和结晶区均属于木材细胞壁的超微构造,是纤维素的结构组成部分。纤维素是植物细胞壁的主要组成成分,也是自然界中分布最广、含量最多的一种多糖,对高等植物细胞壁中天然纤维素结构和形成过程的研究发现,细胞壁超微构造的形成过程并非孤立,而是按照“微晶—微纤丝—结晶区”的顺序形成的。

-

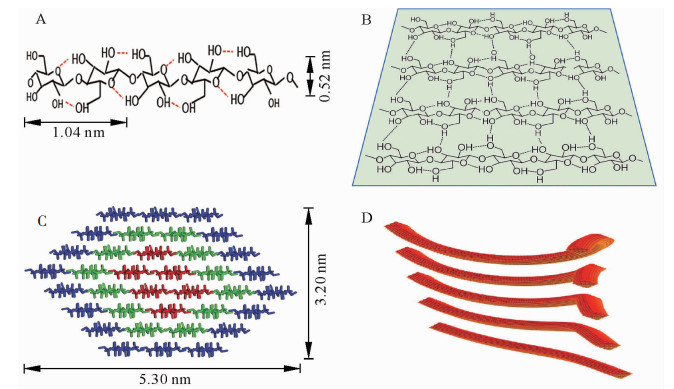

天然状态下,纤维素合成酶合成线性葡聚糖链的聚合度十分庞大(≥104),即上万葡萄糖残基通过β-1, 4-糖苷键相连形成无分支结构的纤维素单链(图 1A)[2-3]。由于含有大量羟基,新合成的相邻纤维素分子链间可产生大量分子间氢键,形成有序自组织聚集体;特别是相邻糖链间形成的氢键,可使纤维素分子形成稳定的片层结构(图 1B)[9];这些片层结构在范德华力和疏水力等次级键作用下自发有序地紧密堆积(图 1C)[10],即为天然结晶纤维素,其中有序结晶的程度可通过X射线粉末衍射法测定的结晶度来表征[11]。由图 1C可知:纤维素基元纤丝中的36根糖链聚集形成8个糖链片层,片层经氢键网络和范德华力作用堆积为空间结构呈现相对规则的六面体;理论模型横切面长约5.30 nm,宽3.20 nm,即常说的纤维素微晶[10]。

-

植物细胞壁微纤丝是在纤维素微晶的基础上形成的。受环境等因素影响,在合成过程中纤维素微晶结构沿着不同晶面聚集生长或沿着某一轴向扭转,形成大小不同、形状各异的微纤丝结构(图 1D)[12]。电子显微镜观测可知,微纤丝中晶胞数目不同,晶面聚集方向不一致[13],微纤丝间不能进一步紧密聚集,因而可认为微纤丝是细胞壁中的基本结构单元(图 1D)。定向排列的微纤丝几何结构发生螺旋状扭曲,造成微纤丝宽度改变的同时,也形成了纤维素结晶和非晶2种晶态[11],即为纤维素的结晶区和非结晶区。

1.1. 细胞壁微晶结构

1.2. 细胞壁微纤丝和结晶区

-

微纤丝角的表征方法随着仪器制造及分析水平的不断发展而发展。直接观测法是最原始的表征方法,适用于细胞壁局部区域微纤丝取向的精细表征,包括直接观测微纤丝倾角的偏振光显微镜法、碘结晶法、激光共聚焦显微镜法、纹孔法、原子力显微镜法以及电子显微镜法等。偏振光显微镜法是最早应用的直接观测法[14],垂直入射的完全偏振光通过试样后出现消光,此消光角即为木材微纤丝角[15]。原子力显微镜法则是通过表征细胞壁中微纤丝聚集体的排列来测定其倾角[16]。

间接法是基于木材光谱特征通过数学计算得到微纤丝角的X射线衍射法、近红外光谱预测法和拉曼光谱法线法等,适用于大量试样的平均微纤丝角的研究[4]。目前比较常用的是X射线衍射法[13-14]。X射线衍射法的微纤丝角计算方法中,Turley法是常用的一种方法,它是通过晶面衍射强度曲线最低2点画切线去除背景的方法计算微纤丝角[17-18]。共聚焦拉曼显微技术和偏振拉曼显微技术则是通过分析与纤维素取向密切相关的拉曼光谱峰来获得细胞壁的纤维素取向[19-20]。

应用直接观测法还是间接观测法应当依据测试要求和内容而定。

-

随着尖端显微镜、射线类以及光谱类仪器不断地应用于木质纤维材料结构与性能表征中,木质纤维材料细胞壁纤维素结晶度、微晶形态等精细构造特征也不断地被揭示。检测方法主要分为原位检测和非原位检测两大类。

原位检测技术不改变样品纤维素原本的位置和形态,常用表征方法如原子力显微镜技术和X射线法。原子力显微镜技术通过监测探针与试样表面的作用力来表征纤维素结晶区等大分子结构特征[21]。X射线法作原位检测时通常以1.0~1.5 mm厚的薄木片为样品,偶有4.0 mm厚的样品[18, 22],作非原位检测以80~100目的木粉压制成的薄片为样品[5, 7],根据衍射最强点的强度和位置,测出纤维素纤维晶体分子链中的晶区大小和结晶度等,能直接获得较为准确的结晶度值。其他非原位检测技术如核磁共振法,以木材硫酸盐浆为实验材料,通过区分纤维素无定形区和结晶区的信号得到结晶度值,其值与X衍射方法得到的结晶度值一致[23]。拉曼光谱法通过拉曼特征峰的相对强度来表征结晶度的大小[24],但因目前无法完全去除半纤维素、木质素等对结晶相关特征峰的干扰,该方法还没有直接应用到木质纤维材料细胞壁微晶形态表征中。

2.1. 微纤丝角表征方法

2.2. 结晶度和微晶形态表征方法

-

树木木质部细胞次生壁在形成过程中,每一薄层的微纤丝沉积方向和排列密度都在不断发生变化,因此木材不同位置的微纤丝角不同[25]。微纤丝角决定材料微观和宏观的各项性能,直接关系到木材加工利用,被认为是影响木质纤维材料性质的重要指标。关于微纤丝角的株内变异规律目前有较多研究。

-

研究认为,径向方向上同一年轮中早材的微纤丝角大于晚材;从髓心(幼龄材)到树皮(成熟材)平均微纤丝角逐渐减小,到一定年龄后趋于稳定。以长白落叶松Larix olgensis为例,从髓心到树皮微纤丝角在生长的前5 a急剧下降,第5年到第25年呈微小的波动变化,与银杏Ginkgo biloba,黑杨Populus nigra,垂枝桦Betula pendula等的微纤丝角变化规律一致[8, 25]。研究发现:云杉Picea aspoerata,垂枝桦和辐射松Pinus radiata等幼龄材的平均微纤丝角约为30°,幼龄材至成熟材变异幅度一般在10°左右,之后基本稳定[26-28]。目前认为:微纤丝角在径向产生这种变异的原因有2种。一种认为树木生长过程中,幼龄期细胞的直径增长快于长度生长,微纤丝轴向伸长受抑制,微纤丝角较大;进入成熟期后细胞长度生长快于直径生长,微纤丝在轴向得以延伸,微纤丝角较小[29]。另一种认为原生质流动方向及原生质体分生的纤维素含量越丰富,微纤丝的排列方向越接近细胞轴的方向;随树龄的增长,光合产物积累越多,分生细胞细胞壁的纤维素含量增多,微纤丝角越小[6]。

-

木材轴向方向微纤丝角的变化规律表现为基部最大,从基部向上先减小后增加的变化趋势,但不同材种变化规律不尽相同。如刺楸Kalopanax septemlobus,油松Pinus tabulaeformis,毛白杨Populus tomentosa中最小的微纤丝角分别出现在1.3 m,3.3 m,5.3 m处;辐射松树高7.0 m以上、毛白杨高9.0 m以上时,微纤丝角趋于稳定,但在梢部的心材中微纤丝角有所增加[6, 30-31]。总体来说,微纤丝角轴向变异模式属于“大—小—大”的形式。目前关于微纤丝角产生轴向变异的原因尚缺乏明确的解释。

-

纤维素的结晶区由纤维素大分子链有序排列形成,结晶区占纤维素整体的百分数即结晶度,可表征木材纤维素聚集态形成结晶的程度。木材纤维素结晶度在不同树种及同一树种不同部位均具有差异性。一般认为:针叶材的纤维素结晶度大于阔叶材。由表 1可知:多数针叶材的平均结晶度大于40%,而阔叶材一般为30%~40%[1, 7, 22, 32-40];但也有例外,如杨树Populus,泡桐Paulownia等低密度阔叶材的纤维素结晶度高于翠柏Calocedrus macrolepis,樟子松Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica等针叶材[7, 32-34]。结晶度的变化也与不同树种细胞生长发育阶段有关。通常认为随木质部细胞的不断发育,纤维素的结晶度会不断增加,且呈正相关。在径向方向的结晶度研究表明,随生长轮龄的增加,结晶度逐渐增大,至成熟后趋于稳定;并且在同一年轮内晚材的结晶度一般比早材的大[5, 36, 41]。目前,对沿树轴方向结晶度变化规律的研究不多,表现为自基部向上逐渐增加,到稍部有所减小[36]。

针叶材 结晶度/% 参考文献 阔叶材 结晶度/% 参考文献 湿地松Pinus elliottii 55 [36] 美国红橡Quercus spp. 36 [22] 马尾松Pinus massoniana 54 [1] 美国樱桃木Prunus serotina 32 [22] 挪威云杉Picea jezoensis > 40 [35] 美国黑胡桃Juglans nigra 38 [22] 杉木Cunninghamia lanceolata 47 [38] 胡桃Juglans regia 39 [37] 樟子松Pinus sylvestris > 40 [32] 小叶杨Populus simonii 35 [39] 臭冷杉Abies nephrolepis > 40 [39] 水曲柳Fraxinus mandshurica < 40 [39] 鱼鱗云杉Picea jezoensis > 40 [39] 白禅Betula platyphylla < 40 [40] 翠柏Calocedrus macrolepis 40 [33] 胡桃楸Juglans mandshurica 35 [39] 落叶松Larix gmelinii 54 [1] 春榆Ulmus davidiana 35 [39] 红松Pinus koraiensis 30-36 [39] 杨树Populus spp. 55 [7] 泡桐Paulownia fortunei 46 [34] Table 1. Crystallinity of the woods in the different tree species

-

天然纤维素中微小尺度的晶粒统称为微晶,常用微晶尺寸表征微晶的形态[42-43]。不同种类木材纤维素微晶的大小和形状并不均一,一般纤维素微晶宽3.00~5.00 nm,厚2.00~5.00 nm,长十至数百纳米,具体形态因树种而异[42]。对5种针叶材树种微晶尺寸的研究发现(表 2),这些针叶材树种的微晶宽度接近,为3.00~3.20 nm,但晶体长度则变化较大,为10.00~40.00 nm[43-46];对银杏幼龄材研究发现,微晶的宽度、长度和树龄相关性不大[43]。目前,关于木材微晶形态在成熟材和幼龄材中变化规律的研究较少。石江涛等[39]发现白桦Betula platyphlla和水曲柳Fraxinus mandschurica等木材早期组织中纤维素的晶型、晶胞或微晶大小与成熟材不同,但具体差别有待于进一步研究。

3.1. 微纤丝角的变化规律

3.1.1. 径向变化规律

3.1.2. 轴向变化规律

3.2. 结晶度的变化规律

3.3. 微晶形态的变化规律

-

微纤丝的排列方向与针叶材管胞的长度和阔叶材纤维的长度相关,微纤丝角是纤维素分子链取向的特征指标,与两者呈不同程度负相关。沿径向方向,生长的前9 a红松Pinus koraiensis的晚材管胞长度自髓心向外急剧增加,而微纤丝角逐渐减小,两者呈显著负相关(-0.965);此后长度增加减缓,微纤丝角也缓慢减小[47]。同一生长轮内两者也呈负相关关系,红松的微纤丝角与管胞长度的相关系数约为-0.70,湿地松Pinus elliottii,油松和翠柏在同一生长轮内管胞长度与微纤丝角的相关系数均为-0.90[34, 47],显示出0.01水平的显著负相关。由此可见,管胞长度与微纤丝角呈显著负相关,一定条件下可以通过管胞长度推测纤丝角度。

阔叶材中微纤丝角与木纤维长度之间也呈负相关,但相关程度要比针叶材低。如尾巨桉Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis细胞壁S2层微纤丝角与纤维长度的相关系数为-0.44[48],欧美杨Populus×euramericana中两者的相关度为-0.39[49]。这可能是因为管胞、纤维长度的变异模式不同;也可能是因为针叶材结构单一,95%以上均是管胞,而阔叶树材中木纤维只占50%左右,组成比较复杂。

-

纤维素结晶度是衡量木质纤维材料细胞壁结晶程度的一个重要指标,与木质纤维材料的生长特性、组织结构等有密切关系。一般来说,结晶度与管胞、纤维长度呈显著正相关。研究发现,翠柏的结晶度与早晚材管胞的长度和宽度相关系数在0.90以上[5];浙江桂Cinnamomum chekiange的结晶度与纤维长度和宽度的相关系数在0.95以上[41]。由此认为,利用木材结晶度可以很好地预测木材细胞形态。

总的来说,目前研究多集中在揭示纤维素微晶形态方面,未深入到对其性能影响方面,因此未来需要加强微晶形态对木质纤维材料基础性能的影响研究。

4.1. 微纤丝角与细胞形态的相关关系

4.2. 结晶度与细胞形态的相关关系

-

对木材细胞壁微纤丝和结晶区的形成过程、微纤丝角和结晶度表征方法及其变化特点进行综述发现,葡萄糖残基最初形成纤维素单链,继而在分子间氢键作用下形成稳定的片层结构,然后通过有序堆积方式形成纤维素微晶;微晶在不同晶面聚集成长,形成相互之间不能再紧密聚集的微纤丝结构,并通过微纤丝的扭曲构象形成纤维的结晶态和非结晶态。微纤丝角和结晶度均可以通过尖端显微镜、射线类以及光谱类仪器设备表征,常用X射线法,此外也用拉曼光谱法等进行表征。结果发现:木材细胞壁微纤丝角和结晶度变化特点在一定程度上表现出相反的变化规律,即径向方向从髓心到树皮微纤丝角逐渐减小,结晶度逐渐增大,最终均趋于稳定;轴向方向从基部向上微纤丝角先减小后增加,结晶度逐渐增加,到梢部有所减小。细胞壁微纤丝的排列和结晶区的大小与其细胞形态相关,微纤丝角越小,管胞和纤维细胞越长,两者呈负相关关系;结晶度越高,细胞越长,两者呈正相关关系。

目前,针对细胞壁微纤丝的形成、倾角变化规律和表征方法等已有较为充分的研究,但关于微纤丝角取向形成机制和细胞壁各层厚度分化形成机理还没有明确的解释;对纤维素微晶形态的研究已兴起,但对从幼龄材到成熟材生长过程中晶型、晶胞及晶体尺寸等微晶形态的具体变化模式还未深入探究。因此,今后工作可以围绕以下几点展开:一是从分子层面探究微纤丝取向形成机理;二是加强对木材细胞壁各层厚度累积过程的研究;三是阐明晶型、晶胞及晶体尺寸等微晶形态在木材生长过程中的变化特点。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: