-

植物通过光合作用固定大气中的碳并产生碳水化合物,不同的碳水化合物在植物生长发育过程中的作用不同[1]。结构性碳水化合物(SC)主要用于植物的结构组织构建,非结构性碳水化合物(NSC)参与植物的生理代谢和渗透调节等过程,是植物进行生理调节的物质基础[2]。葡萄糖、果糖和蔗糖等可溶性糖及淀粉,是NSC的主要组成部分[3]。植物利用可溶性糖调节自身生理状态,同时将部分碳水化合物合成淀粉作为储能物质。当植物面临碳资源不足时,可将淀粉再活化形成可溶性糖以及时补充碳资源[4]。植物体内的NSC水平受生物和环境因素影响较大,土壤水分、气温、光照、损伤、常绿树种的叶龄以及植物自身休眠与否等[5-6]都在不同程度上调控着植物体内的NSC水平[7-8]。除此之外,所有影响植物生长的因素也都会改变NSC在不同器官间的分配格局。NSC及其组分的含量水平是植物在不同生长阶段中碳收支平衡的体现,反映了植物的生长状态和碳代谢差异[9],因此对树木中NSC进行探究是研究树木适应性和固碳潜力的关键。

林分密度和种植点配置是人工林造林的重要技术措施,合理的林分密度和空间配置有助于植株的良好生长,可以优化树木生长的地上空间结构。林分密度与种植点配置共同调控了地上部分和地下根系的协调发展和碳分配格局。不同的造林方式通过改变林分采光时间、光照角度和林分内微环境的气象条件等影响地上冠层的光合作用,同时也作用于林分地下根系生长及其对水肥的吸收效率。研究表明:林分密度影响造林树种的生长状况(树高、胸径等)[10]和林下土壤理化性质[11]等。不同林分密度和栽种配置可构建不同的生长空间,林木在不同的生长空间中调节碳资源在各组织间的分配,加强自身的竞争能力和对环境的适应性。有研究指出:红桦Betula albosinensis幼苗的光合适应性受林分密度的调控,随林分密度的增加,苗木的二氧化碳同化率升高[12]。林分密度对不同树种碳分配的影响各异,高密度林分中紫果云杉Picea pururea针叶中淀粉和可溶性糖含量均表现为较高水平[13],并且林分密度增大也能够促进杂交杨Populus canadensis×Populus maximowiczii向地下部分投资碳资源[14]。然而也有研究表明:苹果Malus × domestica中低密度配置时,具有更高的可溶性糖和NSC含量[15]。当林分密度为中低水平时,林分环境中土壤微生物多样性较高,碳代谢能力更强[16]。林分密度对不同树种NSC含量的影响存在差异,密度影响树木各器官NSC分布仍需进一步探讨。种植点配置对树木的生物特性也有一定的影响,相比于长方形种植点配置,正方形配置中的林分板材质量更优[17],并且林分根系生长空间更加均一,根系对养分的吸收能力更高[18]。然而关于种植点配置对树木内部各器官NSC分布影响的相关研究较少。

NSC代谢是生态系统中植物碳循环过程重要的组成部分[19],对NSC的合理分配和调节是植物生长发育的基础。杨树Populus作为一种快速生长型的落叶乔木,具有明显的生长季和休眠季之分,树木在生长季对养分的快速消耗使NSC在各器官之间的分配特征更加明显。因此,本研究以苏北地区杨树人工林为研究对象,对不同林分密度和种植点配置下树木中NSC的分配和利用进行了研究,以期为营造高效固碳人工林提供科学参考。

-

本研究地位于江苏省宿迁市泗洪林场马浪湖分场(33°33′N,118°32′E),地处江苏中北部洪泽湖西岸,属北亚热带和暖温带季风气候交界区,年平均气温为14.4 ℃,无霜期为197 d,年平均降水量为973 mm,降水主要集中在6—8月,土壤母质为洪泽湖淤积土,土壤质地多为中壤至轻黏。

研究地中栽植的杨树品种为‘南林95’杨Populus × euramericana ‘Nanlin 95’,杨属Populus黑杨派,具有品质优良、环境适应性广、速生等特点,是长江中下游区域人工造林的主栽品种之一。于2007年以1年生带根幼苗进行试验林造林[20]。该试验林以高(400 株·hm−2)、低(278 株·hm−2) 2个种植密度造林,在高、低林分密度下均设置有正方形和长方形2种种植点配置(表1)。不同林分密度和种植点配置下各设置3个30 m × 60 m的试验小区(3个重复),并使用胸径尺和激光测距测高仪(Nikon F550,日本)调查了整个林分中共计632棵杨树的胸径(cm)和树高(m)用于估算生物量。

林分密度/(株·hm−2) 株行距 种植点配置 平均树高/m 平均胸径/cm 土壤pH 400 (高密度) 3.0 m×8.0 m 长方形 21.63 ± 2.30 21.20 ± 2.60 6.69 a 5.0 m×5.0 m 正方形 23.37 ± 3.02 22.21 ± 3.05 6.64 a 278 (低密度) 4.5 m×8.0 m 长方形 23.06 ± 2.30 25.25 ± 3.23 6.54 a 6.0 m×6.0 m 正方形 25.86 ± 2.84 27.15 ± 3.41 6.77 a 说明:土壤pH数据后相同字母表示差异不显著(P>0.05) Table 1. Basic status of experimental stands and basic characters of 0−20 cm soil layer

-

于2018年7月中旬(杨树生长季),分别在高密度正方形配置(400株·hm−2,5.0 m × 5.0 m)、高密度长方形配置(400株·hm−2,3.0 m × 8.0 m)、低密度正方形配置(278株·hm−2、6.0 m × 6.0 m)和低密度长方形配置(278株·hm−2,4.5 m × 8.0 m)的样地中选取2株与标准木相似的、健康、直立、生长状态良好和无病虫害的样株进行取样。每样株取健康叶片(大于30片)和1年生嫩枝(3~5枝,干质量大于10 g),叶和枝样品均采集于冠层中上部向阳位置[21],采样时间为8:00—11:00。使用生长锥在胸径处于南北向、东西向各钻取树干木芯样品2支,在距离根茎50 cm位置处人工挖掘2~10 mm的粗根样品(由于细根采集样本过少,不作为研究对象),将采集好的样品立刻装入配有冰板的保温箱中低温保存并带回实验室备用(<24 h)。在实验室将样品清洗干净后,放入烘箱中65 ℃烘干至恒量,然后用组织研磨仪磨粉,室温避光处保存待测。

-

采用改进的苯酚硫酸法[22]提取样品中的淀粉和可溶性糖,根据可溶性糖和淀粉的不同紫外吸光值,计算单位组织样品中的可溶性糖和淀粉的质量分数(可溶性糖和淀粉占NSC的绝大部分,本研究以可溶性糖和淀粉质量分数之和为NSC总量[23])。

-

根据生物量方程,来估算杨树各器官的生物量[24]。各器官中NSC储量由NSC含量和生物量计算得出,单株NSC储量通过各个器官中NSC储量加权得出,林分NSC储量由林分密度和单株NSC储量计算得到。

式(1) ~ (4)中:W叶为叶生物量;W枝为枝生物量;W干为树干生物量;W根为根生物量;D为胸径(cm);H为树高(m)。

-

采用嵌套方差分析法,分析不同林分密度和种植点配置间杨树人工林总NSC储量以及个体单株叶、枝、干和根中NSC及组分含量的差异性水平,显著水平为0.05。使用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)比较杨树不同器官间NSC及其组分含量的差异性,并使用最小显著差异法(LSD)进行多重对比(P<0.05)。利用Pearson相关分析法,估算杨树各器官NSC及组分含量间的相关关系。以上分析均使用SPSS 23.0完成,用Origin 2017作图。

-

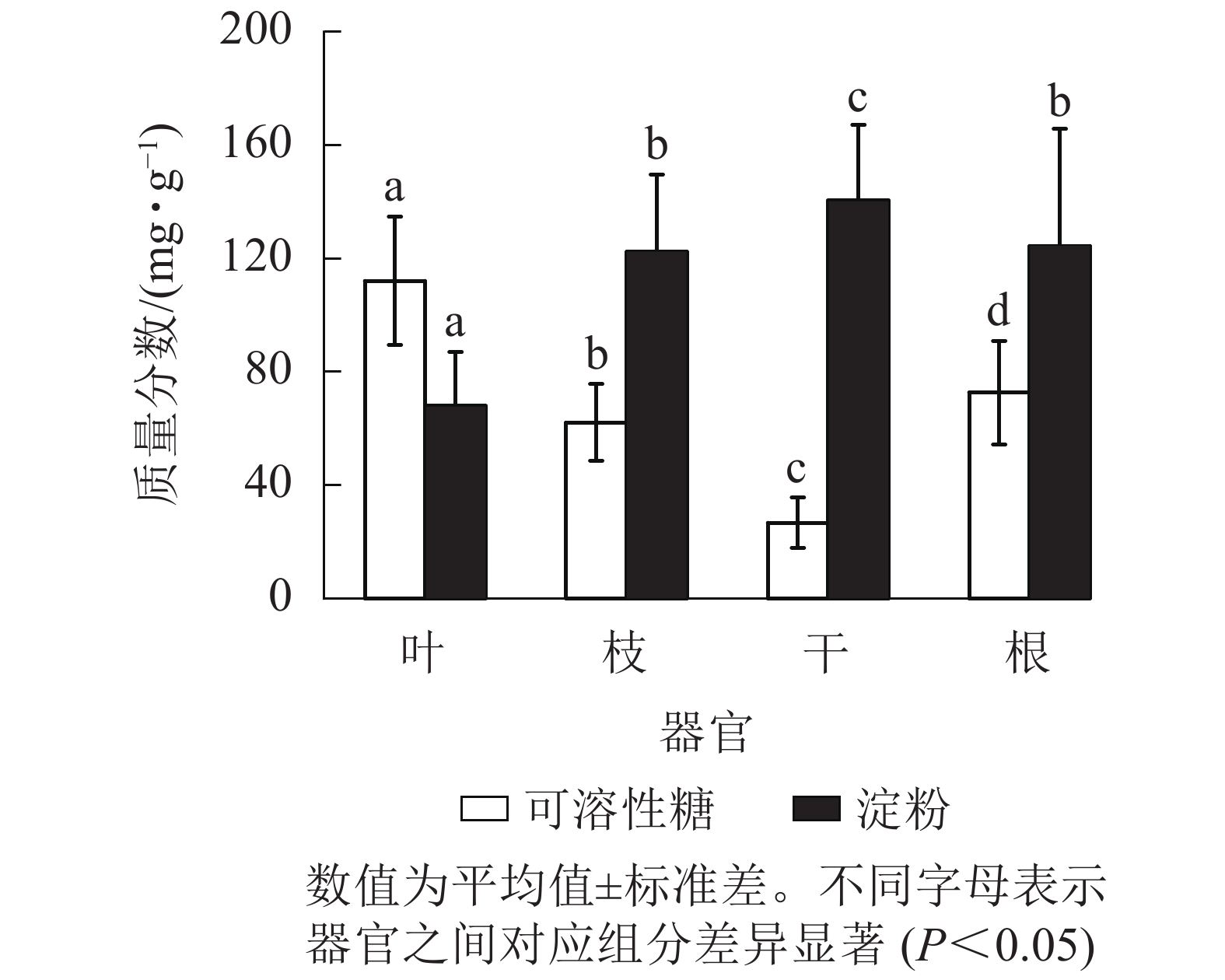

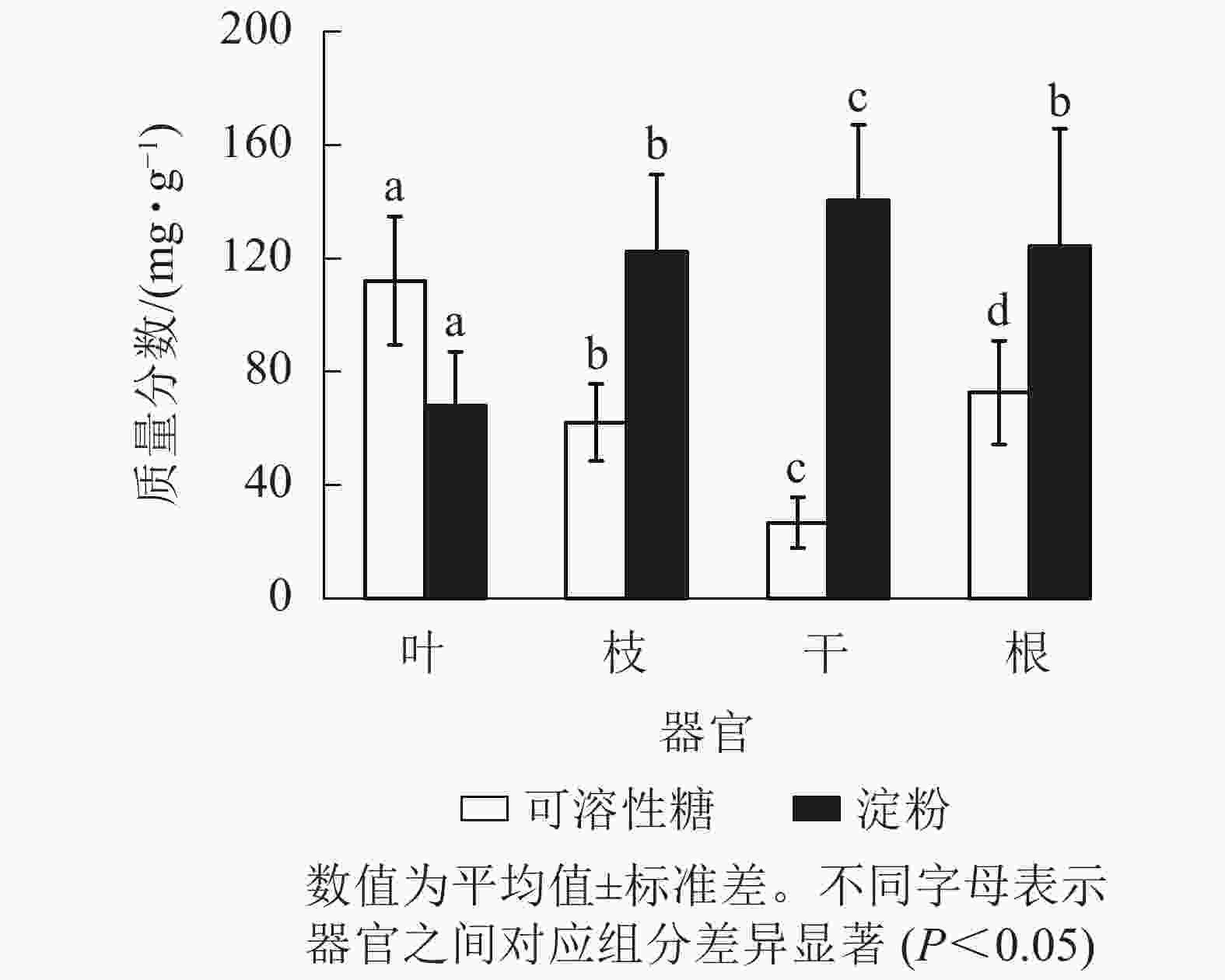

从图1可见:杨树各器官的NSC及其组分质量分数存在显著差异(P<0.05),从叶、枝、到干的可溶性糖质量分数依次递减,到根部有所升高。杨树各器官中的淀粉质量分数从树干位置(最高)开始,向地上部分(枝、叶)和地下部分递减,而NSC总量在各个器官中从大到小依次为根、枝、叶、干。杨树叶、枝、干、根的可溶性糖质量分数占NSC总量的比例分别为62.3%、33.2%、15.9%和36.8%,淀粉质量分数占NSC总量的比例分别为37.7%、66.8%、84.1%和63.2%。

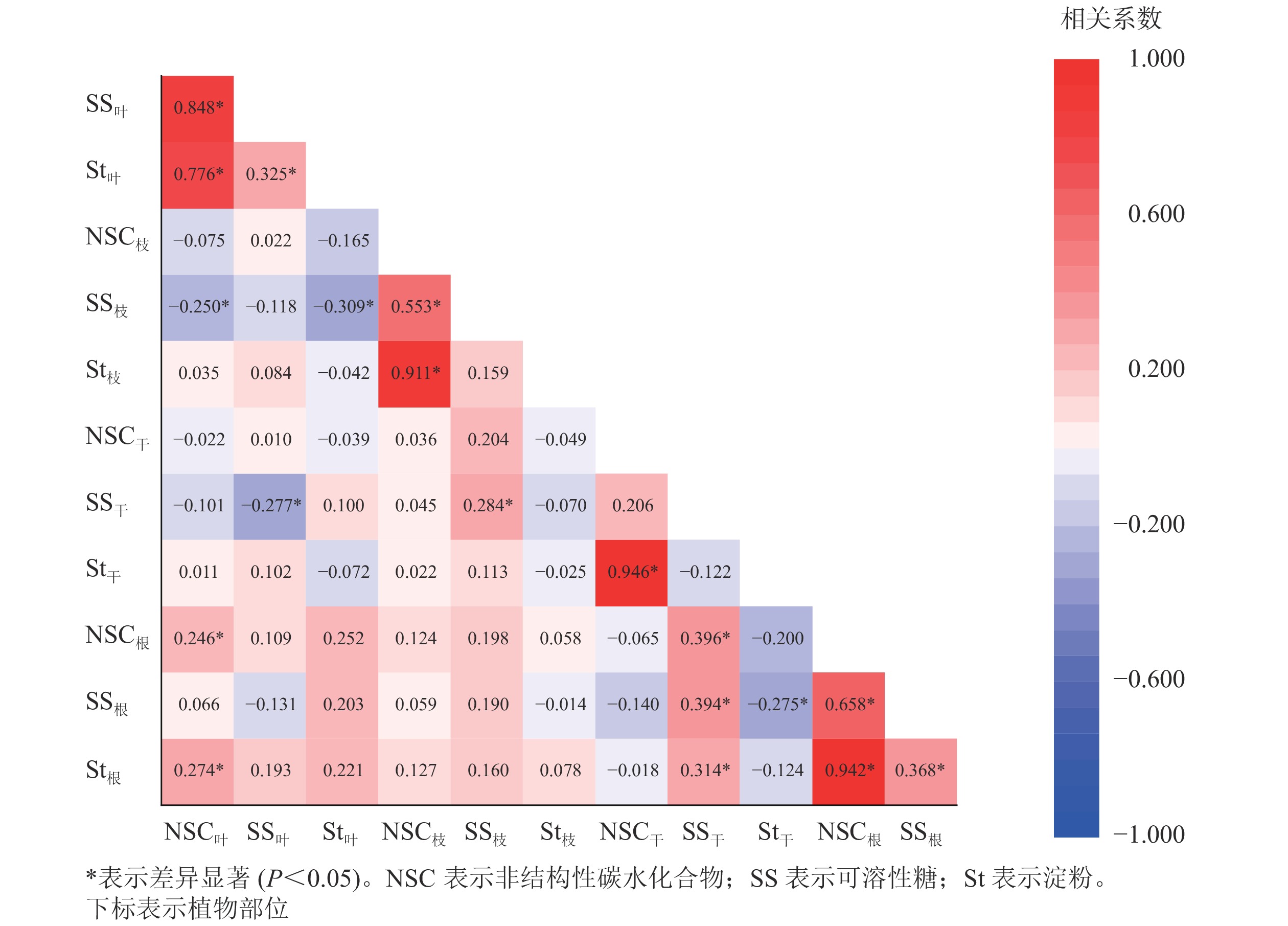

从图2可见:养分利用的就近原则使NSC及组分质量分数的显著相关关系主要发生在相邻器官之间。枝中可溶性糖分别与叶的NSC和淀粉呈显著负相关关系(P<0.05);树干可溶性糖与根的NSC及各组分均为显著正相关(P<0.05)。器官内部(叶、根)对碳资源的利用与储存则主要表现为显著正相关(P<0.05),体现了NSC及组分在不同器官间以及器官内调节与分配关系的多样性。

-

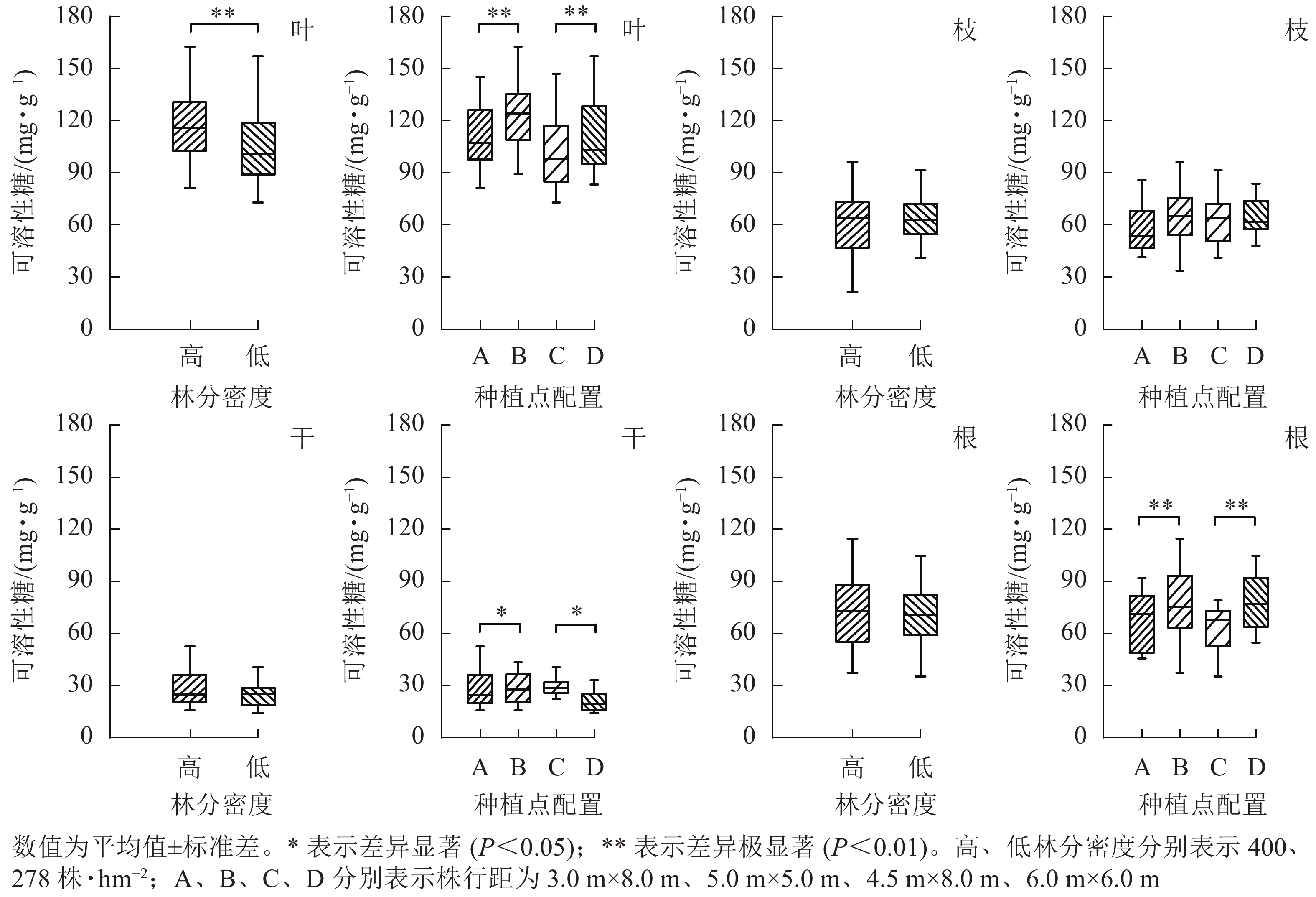

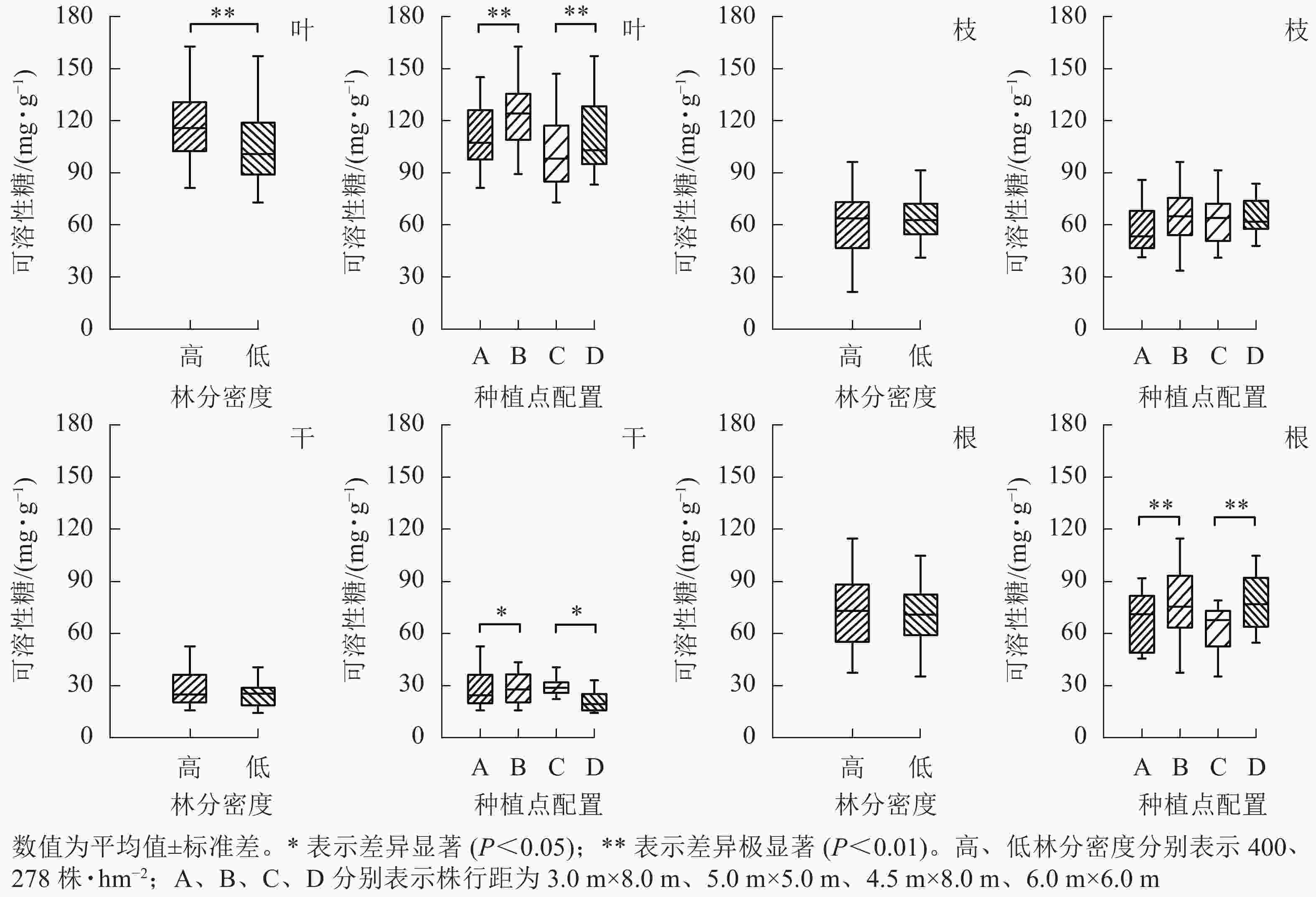

从图3可见:林分密度对不同器官中可溶性糖质量分数的影响存在差异。不同林分密度下杨树叶中可溶性糖质量分数差异极显著(P<0.01),枝、干和根中可溶性糖质量分数则不受林分密度影响。种植点配置对可溶性糖质量分数的影响因器官而异,不同配置下杨树叶、根中的可溶性糖质量分数差异极显著(P<0.01),树干中可溶性糖质量分数差异显著(P<0.05),枝中可溶性糖质量分数在不同配置间差异不显著。

Figure 3. Effect of stand densities and spacing configurations on soluble sugar in different organs of poplar

根与叶中可溶性糖分布相一致,均为同密度下正方形配置高于长方形配置。不同配置林分杨树树干中可溶性糖表现趋势不同,高密度林分表现为正方形配置大于长方形配置,而低密度林分则表现为正方形配置小于同密度下的长方形配置。

-

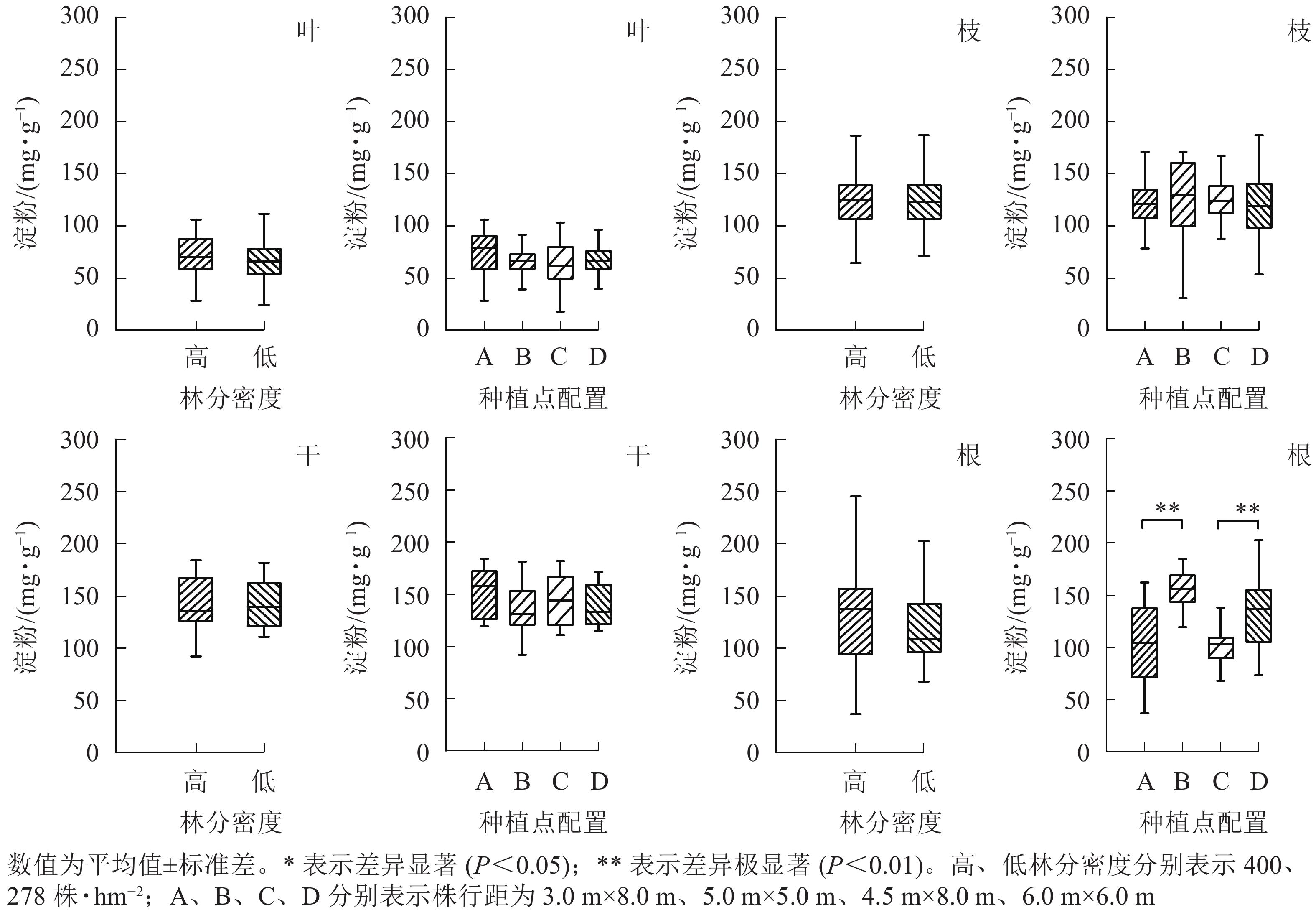

从图4可见:杨树地上部分各器官中淀粉质量分数均不受林分密度和种植点配置的影响。林分密度对地下部分(根)的淀粉影响也不显著,然而不同种植点配置对杨树根中淀粉质量分数的影响差异极显著(P<0.01)。高密度下,正方形配置的杨树根中淀粉质量分数极显著高于长方形配置(P<0.01);与之相似,低密度林分条件下正方形配置的杨树根中淀粉同样极显著高于长方形配置(P<0.01)。

-

从图5可见:杨树叶中NSC质量分数在不同林分密度间差异显著(P<0.05),其他器官中NSC质量分数受林分密度影响差异不显著,高密度林分的杨树叶中NSC质量分数显著高于低密度林分。叶中NSC质量分数受种植点配置的影响显著(P<0.05),根中NSC质量分数受种植点配置的影响极显著(P<0.01),其他器官中NSC质量分数在不同林分密度和种植点配置下差异不显著。整体上,相同林分密度的杨树叶和根中NSC质量分数均表现为对应的正方形配置大于长方形配置。

-

根据生物量估测公式(1) ~ (4),得到单株生物量(表2)。由表2可知:杨树单株生物量在不同林分密度间差异极显著(P<0.01),低密度杨树单株生物量显著大于高密度单株生物量;杨树单株生物量在不同种植点配置间差异极显著(P<0.01)。在林分密度相同的情况下,杨树单株生物量均表现为正方形配置大于长方形配置。

林分密度/(株·hm−2) 单株生物量/(kg·株−1) 种植点配置(株行距) 单株生物量/(kg·株−1) 400 (高密度) 239.28 ± 83.11** 长方形(3.0 m×8.0 m) 216.77 ± 64.03** 正方形(5.0 m×5.0 m) 257.82 ± 91.96** 278 (低密度) 373.41 ± 122.58** 长方形(4.5 m×8.0 m) 325.39 ± 102.73** 正方形(6.0 m×6.0 m) 417.76 ± 122.76** 说明:**表示差异极显著(P<0.01) Table 2. Variance analysis of individual tree biomass in stands with different stand densities and spacing configurations

从图6可见:林分总生物量和林分NSC总储量受种植点配置的影响极显著(P<0.01)。当林分密度为400和278 株·hm−2时,林分总生物量和总NSC储量受林分密度的影响不显著。相同林分密度下林分NSC总储量均表现为正方形配置高于长方形配置。

-

碳资源是植物生长发育的代谢基础,植物按照一定比例将碳分配至各个器官中[3]。杨树的叶、枝、干、根4个器官中,可溶性糖从大到小依次为叶、根、枝、干,淀粉从大到小依次为干、根、枝、叶。糖类在器官间分配格局主要受“源—汇”关系和同化物利用的就近原则影响[9],在叶和根系等生长性强的器官中居多[25],其次是离生长中心较近的器官较多,这与刘万德等[26]的结果相似。而淀粉作为暂时储存物质,当光合产物的消耗大于合成时,淀粉被重新活化为可溶性糖,用于缓冲碳资源不足[27]。因此淀粉主要分布在干、根和枝等储存器官中,叶中仅有少量淀粉存在。然而有研究表明:兴安落叶松Larix gmelinii和红松Pinus koraiensis的根具有较高的可溶性糖[28],这与本研究结果不一致。但是该地区蒙古栎Quercus mongolica可溶性糖含量在器官间的分布与本研究结果相似。此外,蒙古栎和兴安落叶松根中的淀粉含量处于相对较高的水平值[28],这与本研究中树干淀粉最高,根部淀粉次之的结果不一致,这可能由不同针阔树种及气候差异所引起。上述2个树种所处样地年均气温和降水量分别为3.1 ℃和629 mm,而本研究中样地年均气温和降水量分别为14.4 ℃ 和973 mm。长期的低温驯化驱动蒙古栎和兴安落叶松将淀粉更多地转移并储存于地下根系,当低温来临时转化为可溶性糖增加根系细胞中的渗透物质,以避免根系因“根际低温”而出现生长被抑制的现象[29]。相比之下,杨树处于相对温湿的环境中则不需要在根系中储存大量的淀粉来应对低温胁迫,因此淀粉被更多的储存在树干中。尽管根系和树干均为主要的储存器官[30],但还没有明确的研究证明根系和树干储存的主次关系,储存器官的优先级可能受到多种因素影响。本研究中苏北地区杨树在生长季将碳更多地分配到地上部分,把树干作为主要的储存器官,这也可能是杨树生长于该地区所形成的一种适应性策略。

-

人工造林时,较高的碳资源储量是苗木健康生长的重要保障[31]。碳水化合物的含量水平反映了林木的生长状态。整体上,本研究中个体水平上仅叶器官中可溶性糖和总NSC质量分数在不同林分密度间存在显著差异(P<0.05),且杨树叶中NSC及可溶性糖均表现为高密度(400 株·hm−2)大于低密度(278 株·hm−2)。这可能是高密度林分提高了叶片光合作用,进而促使叶中具有较多的光合产物。研究表明:5年生杨树种苗在较高的林分密度能有效地增加冠层的光拦截量,提高冠层的光合效率[32];并且在较低的林分密度中光能可能会被过多的耗散,降低了冠层对光能的利用效率[33]。林分水平的NSC储量在不同林分密度间差异不显著,这与TRUAX等[14]的研究结果一致,可能是研究区种植密度梯度差较小的缘故。

总的来说,在相同林分密度下不同种植点配置间杨树个体和林分水平上的NSC含量及总储量均表现为正方形配置大于长方形配置。与以往研究表明“宽行窄距”林分配置中个体具有更强生长潜力[34]的结论不一致,可能是由于当单株种植面积相似时,“宽行窄距”的配置使个体生长空间有所压缩,个体在正方形配置的林分中具有更加均匀的生长空间,对水分和光能的利用率有所提高[35]。王琪等[18]研究表明:杨树细根对正方形配置的土地空间利用度更高。然而种植点配置对个体的影响具有较大的变异性,当评估种植点配置对个体的效应时,应结合造林密度、造林树种、林龄以及造林地环境条件等因素综合考虑种植点配置对个体的影响。

综上可知,较高的林分密度促进了杨树叶中可溶性糖质量分数的升高。相同林分密度下不同配置间,正方形配置对杨树叶、干和根中NSC质量分数具有促进作用,正方形种植点配置更有利于杨树储备碳资源,促进林分中个体的生长发育。未来进行营林活动时,相同林分密度下应优先考虑正方形的种植点配置,以促进个体积累更多的碳资源,提升个体及林分水平的固碳增汇潜力。

Effects of stand density and spacing configuration on the non-structural carbohydrate in different organs of poplar

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20210223

- Received Date: 2021-03-15

- Accepted Date: 2021-11-12

- Rev Recd Date: 2021-10-30

- Available Online: 2022-03-25

- Publish Date: 2022-03-25

-

Key words:

- soluble sugar /

- starch /

- non-structural carbohydrate(NSC) /

- stand density /

- spacing configuration /

- poplar

Abstract:

| Citation: | CAO Penghe, XU Xuan, SUN Jiejie, et al. Effects of stand density and spacing configuration on the non-structural carbohydrate in different organs of poplar[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2022, 39(2): 297-306. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20210223 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: