-

在全球气候变暖背景下,区域极端高温与强降水事件呈现高频次、高强度发展趋势[1]。随着全球气温的每一次攀升,气候系统的不确定性被显著放大,热浪频发、气候带偏移、干旱常态化等将加剧各类极端天气的复合效应。可以预见,区域气候的剧烈变化会伴随着植物功能性状及其适应策略的改变,但对这一过程背后的数量关系和作用机制仍不清楚[2]。

气候变化的不确定性决定了受控实验的结果存在局限。有研究表明:野外观测结果与受控实验结果并不一致[3]。由于植物功能性状对环境因子响应具有物种特异性,导致许多跨物种研究结论(取性状平均值)在种内水平上失效[4−5]。沿环境梯度生长的常见种栖息于多种气候因子组合且差异巨大的自然生境中,其在各种环境条件下生存所形成的适应策略一直是生态学研究的热点[6]。样带常见种研究既可以最小化系统发育噪声[7],又可以最大化种内性状变异[8],更能准确反映同种植物功能性状及其适应策略的区域分异规律,从而提高气候变化背景下预测植物功能性状变异、植物行为和适应策略的精度。

从中国东南湿润区到西北干旱区,存在一条由降水量和气温驱动的天然植被、土壤梯度带(以下简称降水梯度)。东南湿润区受亚热带海洋性季风气候和热带季风气候的影响,夏季高温多雨,冬季低温少雨,而西北干旱区居于内陆,降水量少,气候干旱。该降水梯度从海岸延伸至内陆腹地,覆盖了从亚热带森林、疏林、灌丛至极旱荒漠的所有生态系统类型,具有极其丰富的物种多样性和植被类型,承载着巨大、多样的生态系统服务功能。2019—2021年,有研究沿降水梯度连续开展3年的野外植被调查,相继确定了榆树Ulmus pumila[5]、银白杨Populus alba[9]、旱柳Salix matsudana[10]、狗尾草Setaria viridis[11]等10个样带常见种,其中也包括本研究的目标植物刺槐Robinia pseudoacacia。

长期以来,由于盲目毁林开垦,沙化地耕种,造成严重的水土流失和风沙危害。为此,中国实施退耕还林工程进行生态恢复[12]。刺槐为豆科Leguminosae刺槐属Robinia落叶乔木,因生长迅速、适应性较强、耐旱等优点得到广泛栽植。但干旱区受到水资源限制,刺槐等生态修复树种面临较高的死亡风险。特别是近年来,以刺槐人工林为代表的植被受到水分的限制日益明显,大量刺槐出现枝梢干枯,甚至整株死亡的衰败现象,不利于生态修复工程的建设[13]。鉴于此,本研究通过比较刺槐叶光合、形态、气孔、解剖、供水等共15个功能性状,探究刺槐功能性状沿降水梯度的区域分异规律及性状间的耦合关系,揭示驱动刺槐功能性状变异的主要气候因子,以期为优化树种选择,制定植被恢复措施提供科学依据。

-

从东南湿润区到西北干旱区,沿降水梯度选择10个国有林场,分别为:安徽宣城宁国市胡乐国有林场、河南信阳南湾实验林场、河南三门峡国营河西林场、陕西铜川宜君县阳湾国有生态林场、甘肃庆阳国营大山门林场、宁夏吴忠国营张家湾林场、甘肃金昌东大河林场、甘肃张掖五泉林场、甘肃酒泉西峰林场和新疆哈密哈铁林场(表1)。这些林场垂直于等降水量线呈带状分布。依据年均降水量将10个地点划分为湿润区(>800 mm)、半湿润/半干旱区(200~800 mm)和干旱区(<

200 mm)。地点 区域 纬度(N) 经度(E) 年均气温/℃ 年均降水量/mm 年均干燥度指数 宣城 湿润区 30.33° 118.77° 16.20 1394.61 0.36 信阳 湿润区 32.06° 113.85° 15.92 1082.29 0.49 三门峡 半湿润/半干旱区 34.48° 110.54° 14.36 555.64 1.15 铜川 半湿润/半干旱区 35.40° 109.14° 10.27 584.43 0.56 庆阳 半湿润/半干旱区 35.88° 108.37° 9.23 581.89 0.66 吴忠 半湿润/半干旱区 36.45° 105.77° 10.65 235.59 2.12 金昌 半湿润/半干旱区 38.33° 102.00° 5.77 226.51 0.73 张掖 干旱区 39.23° 100.17° 8.20 131.71 1.96 酒泉 干旱区 39.67° 98.63° 8.10 81.85 3.37 哈密 干旱区 42.62° 93.44° 10.43 44.17 7.06 Table 1. 10 sampling points and their environmental characteristics

-

在连续3 a的调查取样工作中,确定刺槐[5, 9−11]等10个样带常见种。本研究常见种是指沿降水梯度的10个野外站点附近区域均存在,且无人为干扰痕迹的野外种群。这些常见种中,有些物种并非本地种,是引种后扩散到野外形成的种群,但经过长期适应后形成了与生境相适应的功能性状。如刺槐原产于美国,自18世纪末引入中国后,在23°~46°N,86°~124°E地区均有栽植,具有防风固沙、涵养水源等作用,广泛用于各地的水土保持[14]。在2019和2020年的样带调查中,对上述常见种的野外种群分别设置样地,并测量样地内目标树种的树高、冠幅和胸径等。在此基础上,于2021年对常见种展开了更详细的取样和测量工作,最终确定10个采样点的壮年刺槐进行实验,考虑到对当地气候的适应可能需要比较长的时间,因此选择的刺槐树龄为17~20 a,平均树高为(7.73±0.84) m,平均胸径为(15.67±2.94) cm,平均冠幅为(7.76±0.68) m。每株树选取3根基部直径为6~8 mm的向阳枝条作为重复,所剪枝条长度>50 cm。

-

最新的性状生态学研究表明:植物在水分变化下会展现出一系列的适应策略,即水碳相关的功能性状在不同空间尺度上表现出普遍的变异性和规律性。为揭示植物在干旱胁迫下的生理生态响应机制,本研究选取叶光合性状(最大净光合速率、气孔导度、水分利用效率),气孔解剖性状(气孔大小、气孔密度、气孔面积分数),枝解剖性状(导管直径、导管壁厚、木质部密度),叶解剖性状(栅栏组织厚度、海绵组织厚度),叶形态(比叶重),供水性状(胡伯尔值、叶脉密度、理论枝比导率)共15个关键功能性状指标。

-

每个标记的树枝上选择2片大小一致的叶片,每株树有6个重复,使用LI-6800便携式开放红外气体分析仪,测定刺槐光合参数。室内设置光强为1 200、1 500、1 800 μmol·m−2·s−1,叶室温度控制在25 ℃,二氧化碳(CO2)摩尔分数控制在400 μmol·mol−1。将叶片置于叶室内光诱导20 min,至气孔导度稳定,记录最大净光合速率(Pn,μmol·m−2·s−1)及对应的气孔导度(Gs,mol·m−2·s−1)。Pn除以蒸腾速率(Tr,mmol·m−2·s−1)得到水分利用效率(WUE,μmol·mmol−1)。

-

采用指甲油印迹法[15],将透明的指甲油涂抹叶片背面(避开主脉),待指甲油干燥后,用透明胶带粘在带有指甲油的叶片上,叶片上不要留有气泡。样品带回实验室制成临时装片,置于Leica DM3000显微镜下,在200、400倍放大拍摄气孔成像。每张气孔显微图像至少测量20个气孔长度(Sl)、气孔宽度(Sw),计算气孔大小(Ss=π/4×Sl×Sw,μm2),气孔密度=视野内气孔个数/视野面积。气孔面积分数(Sf,%)为气孔密度(Sd,个·mm−2)和气孔大小(Ss, μm2)的乘积,计算公式为Sf=Sd×Ss×10−4。

-

木质部密度(WD,g·cm−3)为枝段干质量除以枝段新鲜体积获得。用枝剪截取刺槐5~8 cm枝段,排水法测量新鲜枝段体积,编号后将枝段放置在75 ℃烘箱中烘干至恒量,称干质量。固定软化的刺槐小枝用石蜡制成切片,在Leica DM3000显微镜下用50、200倍放大拍摄导管图像,Image-Pro Plus软件分析图像,计算导管壁厚(T,μm),导管直径(D,μm),导管密度(Nv,条·mm−2),水力直径(Dh,μm)[16−17]。

-

将测量叶光合性状所在的枝条编号,去除树皮及髓心后测量内径,计算边材面积(SA, cm2)。摘下枝条上所有的叶片,使用EPSON扫描仪扫描叶片,Image-Pro Plus软件测量叶面积(LA, m2),放在105 ℃烘箱中杀青30 min,再放入75 ℃烘箱中烘72 h得到叶干质量(LM, g)。计算比叶重(LMA=LM/LA, g·m−2)和胡伯尔值(Hv, 103 mm2·cm−2),Hv=边材面积/枝条所有叶面积。

-

从剩余枝条上选择生长良好的叶片,垂直叶片主脉剪取长1.0 cm,宽0.5 cm的叶片样品,固定软化后采用石蜡切片制成永久切片。使用Leica DM3000显微镜放大200倍,拍摄叶解剖结构图像。结合Image-Pro Plus软件测量栅栏组织厚度(PT, μm)和海绵组织厚度(ST, μm)。

-

根据改进的Hagen-Poiseuille方程[17],计算理论枝比导率(Kp, kg·m−1·MPa−1·s−1),Kp=(πρw/128η)×Nv×$D_{\mathrm{h}}^4 $,其中:ρw为20 ℃时的水密度(998.2 kg·m−3),η为20 ℃时的水黏度(1.002×10−9 MPa·s),Nv为导管密度,Dh为水力直径。叶脉密度(Dv, mm·mm−2)为叶脉长度/图像面积[15]。

-

气象数据来源于中国地面气候资料日值数据集V3.0 。借助地理定位系统获取各采样点坐标,气象数据包括年均降水量(MAP)、年均气温(MAT)、干燥度指数(AI)、空气相对湿度(RH)、生长季大气水汽压差(VPD)、生长季光合有效辐射(PAR)、生长季日照时数(SSD),均为1991—2021年的平均值。

各性状指标去除异常值后,对数据进行Shapiro-Wilk正态性检验(如果数据不是正态分布,则进行对数转换)和方差齐性检验。单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA)和Tukey检验比较各性状在不同气候区域间的差异(P<0.05)。通径分析(PSA)探究性状间耦合关系。考虑气候因子存在多重共线性,使用Pearson相关性分析和方差膨胀因子(VIF)筛选气候因子,最终得到年均降水量、干燥度指数、年均气温3个气候因子。采用R软件中的“relaimpo”包进行层次分割(HP)[18]评估这3个气候因子对刺槐功能性状变异的解释率。以上数据处理及图表制作在Excel、Origin 2024、R 4.1.2中完成。

-

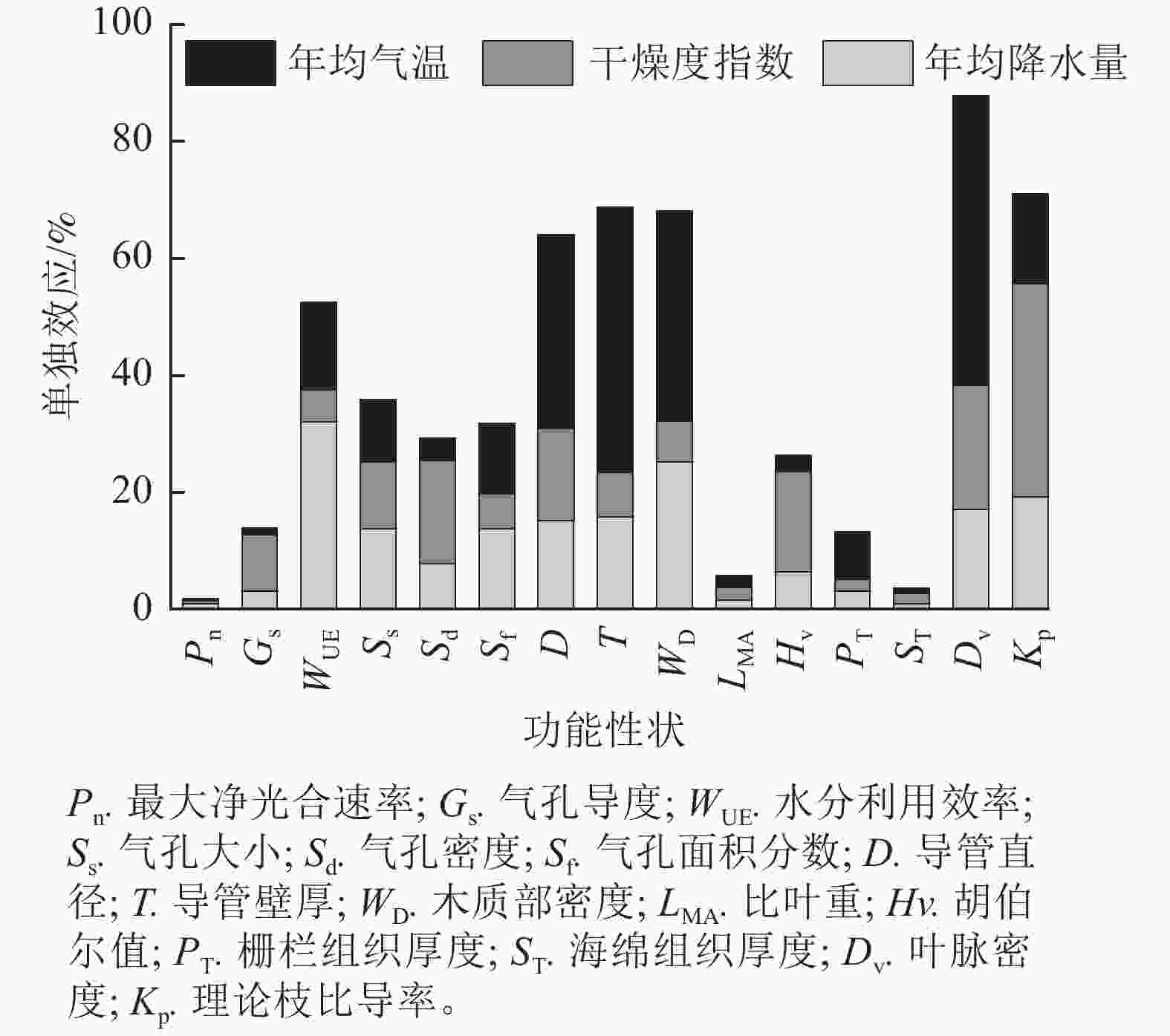

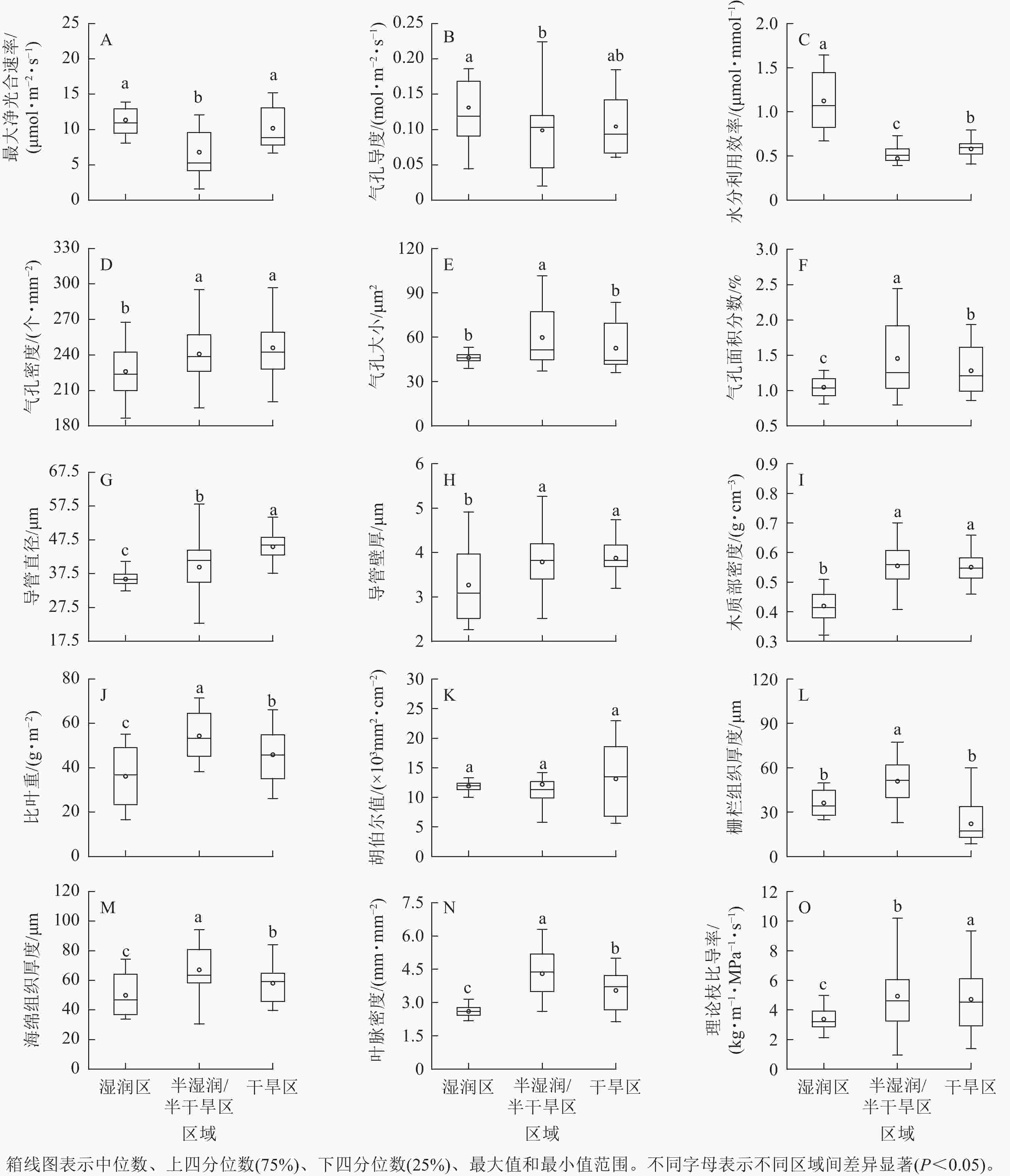

刺槐功能性状中,气孔导度、理论枝比导率是变化最大的2个性状,变异系数分别为50.95%、50.36%。木质部密度、气孔密度是变化最小的2个性状,变异系数分别为14.82%、9.72%(图1)。沿降水梯度,叶光合性状中,最大净光合速率、气孔导度、水分利用效率呈先下降后上升的趋势;气孔性状中,气孔大小、气孔面积分数呈先上升后下降的趋势,气孔密度呈上升趋势;枝解剖性状中,导管直径、导管壁厚呈上升趋势;叶解剖性状中,栅栏组织厚度、海绵组织厚度呈先上升后下降的趋势;供水性状中,理论枝比导率呈上升趋势,叶脉密度呈先上升后下降趋势(图2)。

-

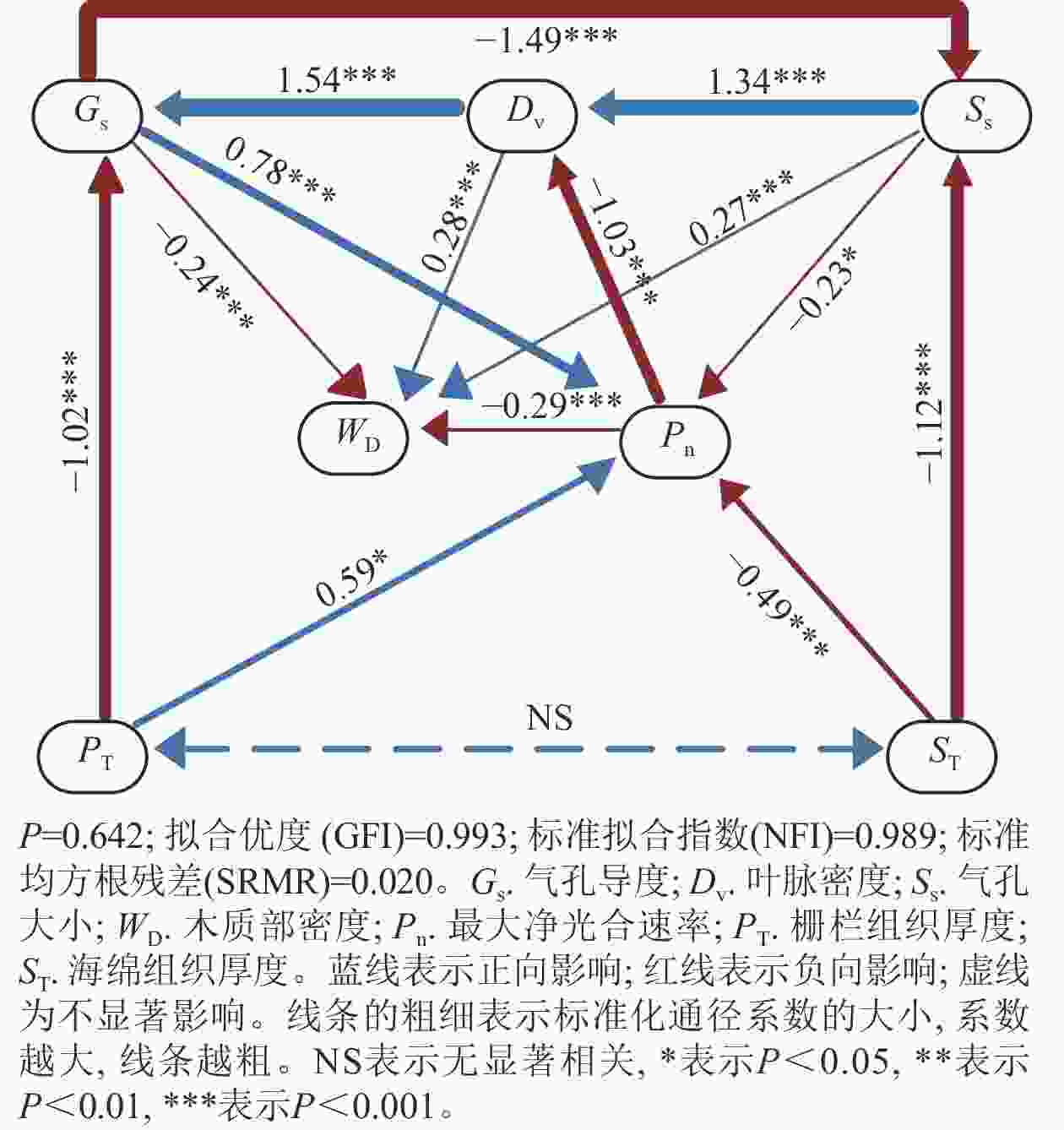

通径分析(图3)显示:刺槐叶光合、气孔、供水性状之间存在较强的因果关系。最大净光合速率的变化归因于气孔导度、气孔大小、栅栏组织厚度、海绵组织厚度,通径系数分别为0.78、–0.23、0.59、–0.49。这些性状中对最大净光合速率影响最大的性状是同为叶光合性状内部的气孔导度。此外,气孔导度的变化归因于栅栏组织厚度、叶脉密度,通径系数分别为–1.02、1.54,对气孔导度影响最大的性状为供水性状内的叶脉密度,而叶脉密度的变化主要归因于气孔大小,通径系数为1.34。

-

整体来看,年均降水量、干燥度指数和年均气温解释了水分利用效率、导管直径、导管壁厚、木质部密度、叶脉密度、理论枝比导率等6个功能性状50%以上的变异。除胡伯尔值外,枝解剖性状和供水性状受上述气候因子的影响大,气候因子对其解释率为60%~90%,其中年均气温对枝解剖性状变异的相对影响大于干燥度指数与年均降水量(图4)。

Figure 4. Individual effect of mean annual precipitation, aridity index, and mean annual temperature on variations of functional traits of R. pseudoacacia

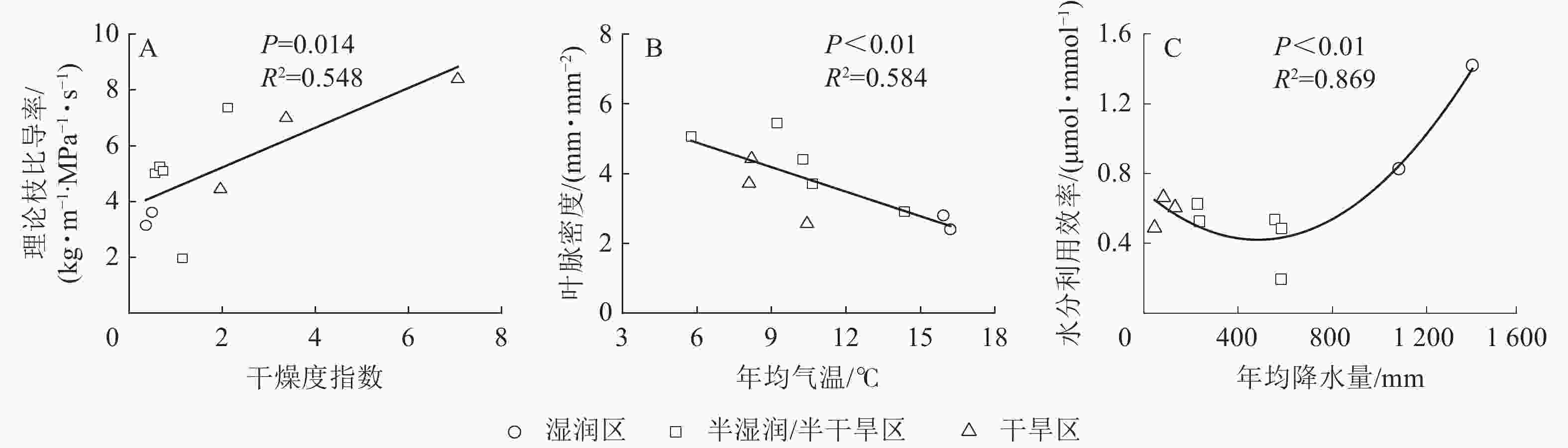

刺槐的15个功能性状中,干燥度指数对气孔导度、比叶重、胡伯尔值、气孔密度、海绵组织厚度、理论枝比导率变异的解释率较大,其中干燥度指数对理论枝比导率变异的解释率最大,达36.45%。年均气温对栅栏组织厚度、导管直径、导管壁厚、木质部密度、叶脉密度变异的解释率较大,其中年均气温对叶脉密度变异的解释率最大,达49.48%。年均降水量对最大净光合速率、水分利用效率、气孔大小、气孔面积分数变异的解释率较大,其中年均降水量对水分利用效率变异的解释率最大,达31.96%(图4和图5)。干燥度指数是影响刺槐功能性状变异的主要驱动因子,其次是年均气温和年均降水量。

-

植物通过气孔控制叶片与外界环境的水气交换,其中气孔密度和气孔大小等性状显著影响光合作用和蒸腾作用。本研究表明:在干旱条件下,气孔大小先增大后减小,以减少植物水分流失,这与XIE等[5]的研究结果一致。然而,榆树的气孔大小和气孔密度通过相反的变化趋势共同调节气孔的面积分配以维持水分平衡。相比之下,刺槐的气孔密度随干旱程度加深持续增大,维持了刺槐在干旱区相对较高的气孔面积分数。同时,随着干旱程度的加深,叶脉密度增加以增强植物输水能力,即使在干旱区叶脉密度也显著高于湿润区(干旱区的叶脉密度是湿润区的1.4倍)。同样刺槐的枝条在干旱区也表现出较高的水分运输效率,实现了水分供需平衡。沿降水梯度,刺槐通过增大导管直径提高输水效率,间接促进光合气体交换;但大直径导管在干旱环境下往往容易诱发栓塞,不利于植物抗旱[19−23]。

为了补偿这种“激进”(高气孔面积分数与高水分传输率)的用水策略,刺槐通过发育高密度的气孔来控制水分流失以提高用水效率,干旱区水分利用效率的升高验证了这一点[24]。此外,刺槐枝条增加导管壁厚为抗旱性提供了结构基础,同时刺槐木质部密度在半湿润/半干旱区显著增加。木质部密度是耐旱性的重要指标,木质部密度越高,说明木质部对干旱诱导的空化抵抗能力越强[25]。党维等[26]对6个耐旱树种木质部结构与栓塞修复能力的研究发现:刺槐的栓塞修复能力最大,允许植物部分栓塞以提高对水资源的利用能力。这种较强的空化抵抗能力和栓塞修复能力,可能是刺槐在干旱区依然保持水分运输高效性的原因。

刺槐各功能性状沿降水梯度表现出不同程度的变异,变异较大的性状(气孔导度、理论枝比导率)与变异较小的性状(木质部密度、气孔密度)有4~5倍的差异。气孔导度的变异系数最大,说明气孔对干旱环境的反映较为灵敏,像“阀门”一样控制着水分蒸腾和CO2进出[27]。MENCUCCINI等[28]研究发现:叶片相关的性状(理论枝比导率、比叶重、胡伯尔值等)比枝解剖结构更容易受到环境的影响,而本研究中比叶重、胡伯尔值的变异系数为27.2%、38.2%,并非刺槐变异最大的性状。总体而言,刺槐叶功能性状的变异系数大于枝解剖性状,这可能是因为叶片是植物与环境进行物质-能量交换的主要器官,性状更容易受环境变化的影响[29]。

-

干旱导致植物水分供给不足,引起水分运输系统的栓塞,对其造成不可逆的损害[30]。同时,植物光合生理过程受到水力作用的限制,木质部运输的水分必须能够补充植物因CO2吸收过程中气孔流失的水分[31−32]。因此,大量理论和实证表明:水力与光合作用之间存在紧密的协调关系[33−34]。本研究中,刺槐通过协调供水与气孔性状,并调整光合性状,提高输水能力和减少水分流失,以适应干旱环境并维持生存。

刺槐通过增加叶脉密度,提高气孔密度,增强植物的输水能力,进而提升最大净光合速率,以获取更强的竞争力。SACK等[35]研究发现:植物通过提高叶脉密度和气孔密度来满足水分需求,从而获得较高的气孔导度和气体交换速率。此外,叶光合性状中,气孔导度和最大净光合速率沿降水梯度变化呈现高度一致性,较高的光合速率依赖于较高的气孔导度。从湿润区到干旱区,气孔导度和最大净光合速率均增加,表明刺槐在干旱条件下表现出机会主义和快速生长的特性[36−37]。

另一方面,气孔对环境变化高度敏感,通过快速调节气孔导度减少水分流失。水分流失的减少主要通过2种途径实现:①短时间内调节气孔导度;②长期适应中改善气孔结构,如气孔大小和气孔密度[29]。通径分析表明:气孔导度的变化也归因于气孔大小,即气孔的发育与运动受气孔大小的调节,这与FRANKS等[24]的研究结果一致。在缺水环境中,气孔保持开放以维持光合作用,同时优化水分利用效率。结合高水分供应能力(叶脉密度),刺槐在水分胁迫下仍能保持较高的生长速率。

-

植物会随着环境变化而调整叶片和枝条功能性状,使其能够在不同环境条件下存活。已有许多研究调查气候对植物功能性状的影响,但由于环境变量不同导致对植物功能性状的影响不同。ZHANG等[38]对生长在黄土高原不同降水梯度的油松Pinus tabulaeformis研究发现:年均降水量是叶片功能性状变化的主要环境因子,然而对中国西北地区316种被子植物和全球2 332种被子植物的研究表明:年均气温是影响植物导管直径变异的主要气候因子[39]。本研究发现:沿降水梯度刺槐功能性状变异主要受年均降水量、干旱度指数、年均气温的影响,其中干燥度指数是影响刺槐功能性状变异的主要气候因子。

干燥度指数是温度和湿度状况的组合,经常被用来描述气候干旱的程度。对澳大利亚东部120种被子植物的水力性状研究发现:水力性状与生长季节的干旱指数呈显著正相关[40]。本研究发现:干燥度指数是影响刺槐功能性状变异的主要气候因子,其中理论枝比导率受干燥度指数影响最大,随着干燥度指数的增加,相对干旱的环境使植物的生存受到环境的胁迫,刺槐通过增大理论枝比导率维持较高的枝条水分传输效率,用水策略较为激进。同时,干燥度指数也是影响气孔导度变异的主要气候因子,气孔导度可能通过性状间的协调以响应大气干燥程度的增加,从而减少叶片蒸腾损失。

刺槐的供水、枝解剖性状对气候变化较为敏感。供水性状通过保证植物体内水分供应来满足植物生长发育所需的水分,而枝解剖性状为刺槐的抗旱性提供稳定的结构基础,通过优化气孔导度与气孔大小来改变刺槐的最大净光合速率,保持了枝解剖性状沿降水梯度的稳定性变化,这与ZHANG等[38]的研究结果相同。此外,刺槐功能性状都存在未被气候因子解释的部分,可能受到地形、小气候和土壤理化性质等复杂环境因子作用,也可能是不同的物种对环境变化的响应模式存在较大差异,因此在大尺度梯度上,需要加入更多的物种和复杂的环境因子来探究植物功能性状变化的环境驱动因素。

-

刺槐功能性状沿降水梯度表现不同程度的变异,变异最高的2个性状为理论枝比导率和气孔导度,变异最低的2个性状为木质部密度和气孔密度。区域分异规律性状变异及和性状间耦合反映了刺槐的生态适应策略:刺槐通过增大气孔面积分数、导管直径、理论枝比导率实现相对较高的水分运输效率,用水策略较为激进,同时增加导管壁厚、木质部密度为上述激进的用水策略进行补偿。分析结果表明:刺槐通过供水、气孔性状间紧密协调并调整叶光合性状来适应干旱,即增加叶脉密度,提高气孔导度,进而增大最大净光合速率,以适应不断变化的环境。年均降水量、干燥度指数、年均气温对枝解剖、供水性状变异的解释率较高,干燥度指数是驱动沿降水梯度分布的刺槐功能性状变异的主要气候因子。

Adaptive strategies of twig functional traits in Robinia pseudoacacia along a precipitation gradient and their driving mechanisms

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20240623

- Received Date: 2024-11-25

- Accepted Date: 2025-03-27

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-03-13

- Available Online: 2025-05-30

- Publish Date: 2025-05-30

-

Key words:

- plant functional traits /

- climate change /

- intraspecific variation /

- driving factor /

- Robinia pseudoacacia

Abstract:

| Citation: | DING Xinxin, TANG Luyao, ZHANG Bona, et al. Adaptive strategies of twig functional traits in Robinia pseudoacacia along a precipitation gradient and their driving mechanisms[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2025, 42(3): 503−512 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20240623 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: