-

硫代葡萄糖苷(glucosinolates,GSL)简称硫苷,是一类富含硫、氮的阴离子型次生代谢物[1],主要分为脂肪族硫苷(aliphatic glucosinolates,AGSL)、吲哚族硫苷(indole glucosinolates,IGSL)和芳香族硫苷(aromatic glcosinolates)[1−2]。目前已在十字花科Brassicaceae植物中被发现,并鉴定出200余种硫苷化合物[1, 3−5]。GSL作为一类重要的抗病次生代谢物,在芸薹属Brassica植物中检测出40多种,特别是在芥菜Brassica juncea叶片中含量最高[6−8]。核盘菌Sclerotinia sclerotiorum为子囊菌亚门Ascomycotina下的真菌,其主要通过子囊孢子侵染白菜B. rapa、芥菜、油菜B. napus等10余种十字花科作物[9−12]。研究表明:硫苷在十字花科植物抗病防御中发挥核心作用,通过激活黑芥子酶系统生成异硫氰酸酯,有效抑制核盘菌侵染[13−14]。羽衣甘蓝B. oleracea var. acephala中主要防御组分2-丙烯基硫苷(sinigrin,SIN)的积累水平与菌核病抑制率呈剂量依赖性正相关[15]。芥子素、吲哚族硫苷及脂肪族硫苷生物合成缺陷的突变体植株由于硫苷代谢通路受阻,导致核盘菌病斑扩展速率较野生型提高2.3倍[14]。MANN等[16]基于CRISPR/cas9编辑芥菜中硫代葡萄糖苷转运体(GTR)家族基因,使其硫苷硫代葡萄糖苷含量在种子中较低,同时在其他植物部位保持高硫苷水平,从而不损害植物防御,间接证明芥菜中硫苷可有效抵御核盘菌入侵。

芥菜是十字花科芸薹属1年生草本植物,由白菜AA基因组和黑芥B. nigra BB基因组杂交形成的一个天然异源四倍体[17],经过漫长的进化过程后,演化出根、茎、叶、薹、芽、籽等六大类型变种[18−19]。研究表明:芥菜包含大量的维生素C、矿物质元素和膳食纤维,具有较高的营养价值[20]。同时,因芥菜富含以2-丙烯基硫苷为代表的硫苷类物质及高产等特性,在蔬菜生产和加工领域具有重要价值。鉴于硫苷在植物防御反应中的作用,解析芥菜硫苷与抗病性间的互作关系对培育优质抗病品种具有重要意义。本研究以8个芥菜品种为材料,在其“四叶一心”时期进行病原菌接种处理,通过高效液相色谱(HPLC)法测定8个芥菜品种的硫苷组分和质量摩尔浓度,并通过活体接种核盘菌试验,鉴定不同芥菜品种叶片中硫苷质量摩尔浓度及组分的异同和对核盘菌侵染的抗性,为芥菜等十字花科植物抗病新品种的选育和遗传改良提供科学参考。

-

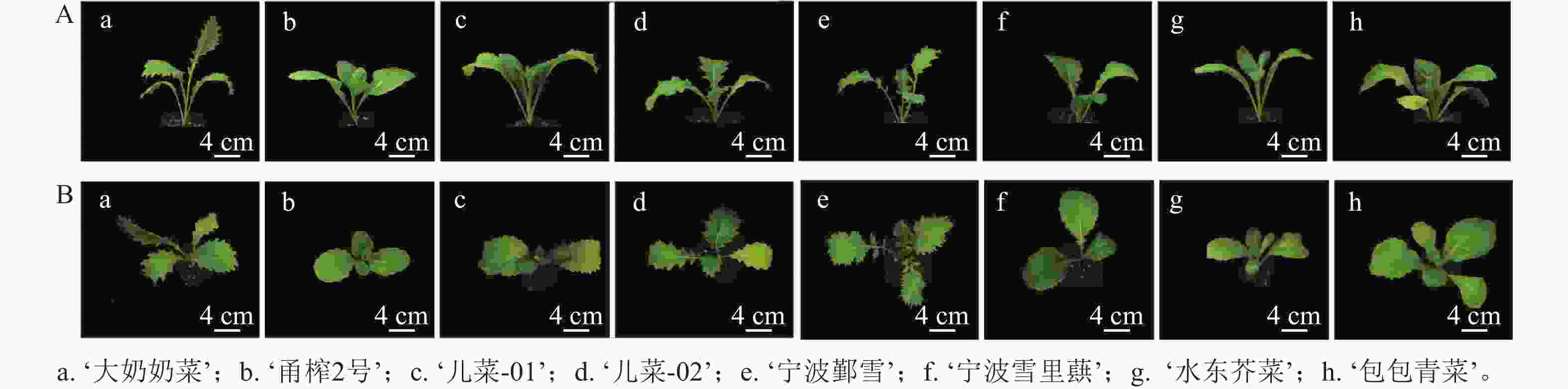

以4个茎用芥菜B. juncea var. tumida品种[‘大奶奶菜’‘Danainaicai’(购于四川泸旺种业有限公司)、‘儿菜-01’‘Ercai-01’(宁波农科院赠)、‘儿菜-02’‘Ercai-02’(宁波农科院赠)、‘甬榨2号’‘Yongzha No. 2’(宁波农科院赠)]和4个叶用芥菜B. juncea var. rugosa品种[‘宁波鄞雪’‘Ningboyinxue’(宁波农科院赠)、‘宁波雪里蕻’‘Ningboxuelihong’(宁波农科院赠)、‘水东芥菜’‘Shuidongjiecai’(购于广州翔启蔬菜种子有限公司)、‘包包青菜’‘Baobaoqingcai’(四川蜀信种业有限公司)]为材料。芥菜种植于V(草炭)∶V(蛭石)∶V(珍珠岩)=3∶2∶1的混合基质中,置于光照培养箱栽培,培养箱温度为22 ℃(昼)/18 ℃(夜),光照强度为20 000 lx,相对湿度为60%~70%,16 h光照/8 h黑暗循环。于芥菜生长至“四叶一心”时进行实验。

-

从−80 ℃取出的核盘菌菌核(保存于浙江农林大学园艺科学学院)置于马铃薯葡萄糖琼脂培养基(PDA)平板上,倒置于22 ℃培养箱,黑暗处理3~5 d进行复苏,后取核盘菌菌丝于PDA平板上,倒置于22 ℃培养箱,黑暗培养约3 d进行大量扩繁。

-

每个品种随机选取10株,设置6次生物学重复。提取及分析硫苷方法在相关研究[21−23]基础上略作修改,具体步骤如下:①混合称取0.4 g植物组织,用4 mL双蒸水(ddH2O)沸煮10 min,于定量滤纸进行过滤,取上清。②向上述植物组织重复加入4 mL ddH2O沸煮10 min,于定量滤纸进行过滤,取上清,将2次上清液混合一起。③向上清液中加入100 µL 5 mmol·L−1的金莲葡萄糖硫苷(glucotropaeolin)作为内标。④将能吸附弱酸根离子固相萃取柱用ddH2O清洗,加入1 mL 25 mg·mL−1 DEAE Sephadex A25和200 µL 40 mg·mL−1二氧化硅(SiO2)。⑤待萃取柱形成3层层析后,取5 mL上清液进行硫苷萃取,萃取过程可适当施加压力促进滤液流出,待上清液流尽后,加入等量的ddH2O进行清洗。⑥待萃取液全部流完后,加入200 µL 1 mg·mL−1的硫酸酯酶。⑦将萃取柱上下两头用封口膜封口,于30 ℃水浴锅中恒温反应12 h,促进硫苷脱硫。⑧用3 mL超纯水将上述脱硫硫苷过柱洗脱,后用0.45 mm滤膜过滤洗脱液,保存于HPLC分析进样瓶(避光),−80 ℃保存。⑨采用Waters ACQUITY Arc系统对样品进行分析。流动相的组成成分:超纯水和乙腈;梯度条件:0~45 min、45~60 min;乙腈体积分数线性梯度:0~20%。色谱柱:C-18 反相柱(250 µm×4 µm,5 µm,Bischoff,Leonberg,德国);柱温:30 ℃。进样量:20 µL。检测波长:229 nm,流速1 mL·min−1。⑩各组分硫苷质量摩尔浓度根据金莲葡萄糖硫苷值和相应的相关系数进行计算。

-

参照相关研究方法[10]接种核盘菌。于芥菜‘四叶一心’时期选取长势相似且状态良好的植株,用灭过菌的中枪头(直径5.3 mm)沿菌落边缘倒扣取接种菌块,注意菌丝长势应一致。将带有菌丝的一面接种到第3及第4片真叶主叶脉消失的地方,轻轻按压使其紧贴叶面,最后覆膜进行保湿处理。将植株放于(20±2) ℃的光照培养箱中正常生长,在0、12、24和36 h时进行表型观察。

-

分别于0、12、24和36 h对各材料的接菌叶片表型进行观察和拍照记录,使用ImageJ软件进行菌斑面积的测量与计算。每组数据进行10次独立生物学重复,3次技术重复。

-

采用SPSS Statistics进行统计分析。结果以平均值±标准差表示。显著性分析采用one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test检验或Duncan’s多重检验进行检验评估,显著性水平为0.05。采用GraphPad Prism 8.0作图。

-

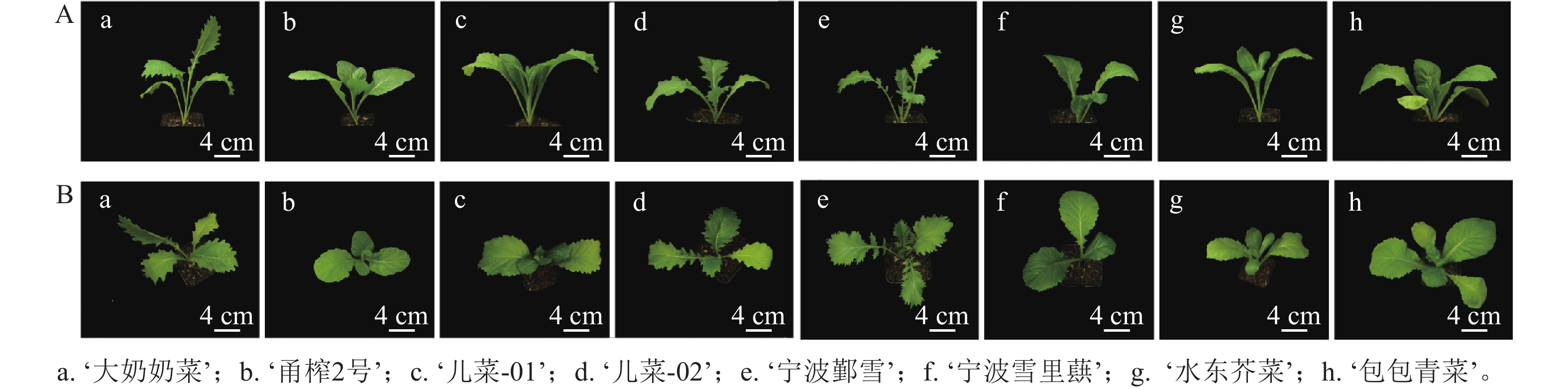

如表1和图1所示:茎用芥菜的植株高度大于叶用芥菜,而叶用芥菜的株幅更大,植株更为健壮。不同品种芥菜的叶片形态存在差异,‘大奶奶菜’和‘甬榨2号’的叶片呈长条形,叶缘锯齿明显;‘儿菜-01’和‘儿菜-02’的叶片锯齿较浅,叶面积较大;‘宁波鄞雪’的叶片为羽状深裂,‘宁波雪里蕻’‘水东芥菜’和‘包包青菜’的叶片均为卵圆形,叶缘锯齿较少。虽然叶用类芥菜的叶片形态较为统一,但不同品种间的叶面积差异仍较为明显。

表 1 8个芥菜品种的主要生长表型

Table 1. Main growth phenotypes of 8 mustard cultivars

品种 株高/cm 株幅/cm 叶片面积/cm2 ‘大奶奶菜’ 18.131±1.741 a 22.741±1.517 bc 37.178±4.875 ab ‘甬榨2号’ 17.348±1.989 ab 23.475±3.135 bc 22.438±2.809 c ‘儿菜-01’ 14.799±3.317 abc 22.909±1.981 bc 28.962±6.577 bc ‘儿菜-02’ 13.533±3.497 bcd 19.066±1.387 c 30.529±6.337 bc ‘宁波鄞雪’ 13.373±1.626 bcd 24.567±3.755 ab 24.244±3.119 c ‘宁波雪里蕻’ 9.857±1.876 d 26.671±3.487 ab 31.790±2.606 bc ‘水东芥菜’ 12.635±1.688 cd 29.030±3.728 a 28.858±5.951 bc ‘包包青菜’ 10.121±0.594 d 24.919±1.507 ab 41.555±6.464 a 说明:不同字母表示同一指标不同品种间差异显著(P<0.05)。 -

从表2可见:8个芥菜品种叶片硫苷质量摩尔浓度为1.851~4.844 µmol·g−1。总硫苷和脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度变化趋势一致,‘甬榨2号’最高,除与‘大奶奶菜’无显著差异外,与其余品种均存在显著差异(P<0.05),‘儿菜-02’和‘宁波雪里蕻’最低。2-丙烯基硫苷质量摩尔浓度变化则呈现一定差异,‘甬榨2号’最高,其次为‘大奶奶菜’,而‘儿菜-02’最低。在叶用芥菜中,‘宁波鄞雪’的脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度最高,‘宁波雪里蕻’最低。相反,吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度在‘儿菜-02’中最高,其次为‘宁波雪里蕻’和‘儿菜-01’,‘大奶奶菜’最低。2-丙烯基硫苷质量摩尔浓度在所有品种中占总硫苷的95%以上,表明其在不同品种芥菜的硫苷组成中均占据主导地位。

表 2 8个芥菜品种的硫苷组分质量摩尔浓度

Table 2. Glucosinolate component contents in 8 mustard cultivars

品种 总硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 脂肪族硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 吲哚族硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 2-丙烯基硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 2-丙烯基硫苷/总硫苷/% ‘大奶奶菜’ 4.725±0.615 ab 4.719±0.614 ab 0.006±0.001 c 4.690±0.623 a 99.26 ‘甬榨2号’ 4.845±0.593 a 4.831±0.593 a 0.013±0.003 de 4.732±0.562 a 97.70 ‘儿菜-01’ 2.735±0.256 de 2.710±0.257 de 0.025±0.003 b 2.648±0.234 cd 96.79 ‘儿菜-02’ 1.800±0.335 f 1.766±0.336 f 0.035±0.002 a 1.728±0.324 e 95.95 ‘宁波鄞雪’ 3.915±0.433 bc 3.899± 0.434 bc0.017±0.002 cd 3.861±0.427 ab 98.61 ‘宁波雪里蕻’ 1.851±0.617 ef 1.820±0.616 ef 0.031±0.002 a 1.793±0.601 de 96.86 ‘水东芥菜’ 2.549±0.310 def 2.532±0.311 def 0.017±0.003 c 2.507±0.312 cde 98.34 ‘包包青菜’ 3.376±0.292 cd 3.360±0.290 cd 0.016±0.002 cd 3.236±0.286 bc 95.88 说明:不同字母表示同一指标不同品种间差异显著(P<0.05)。 -

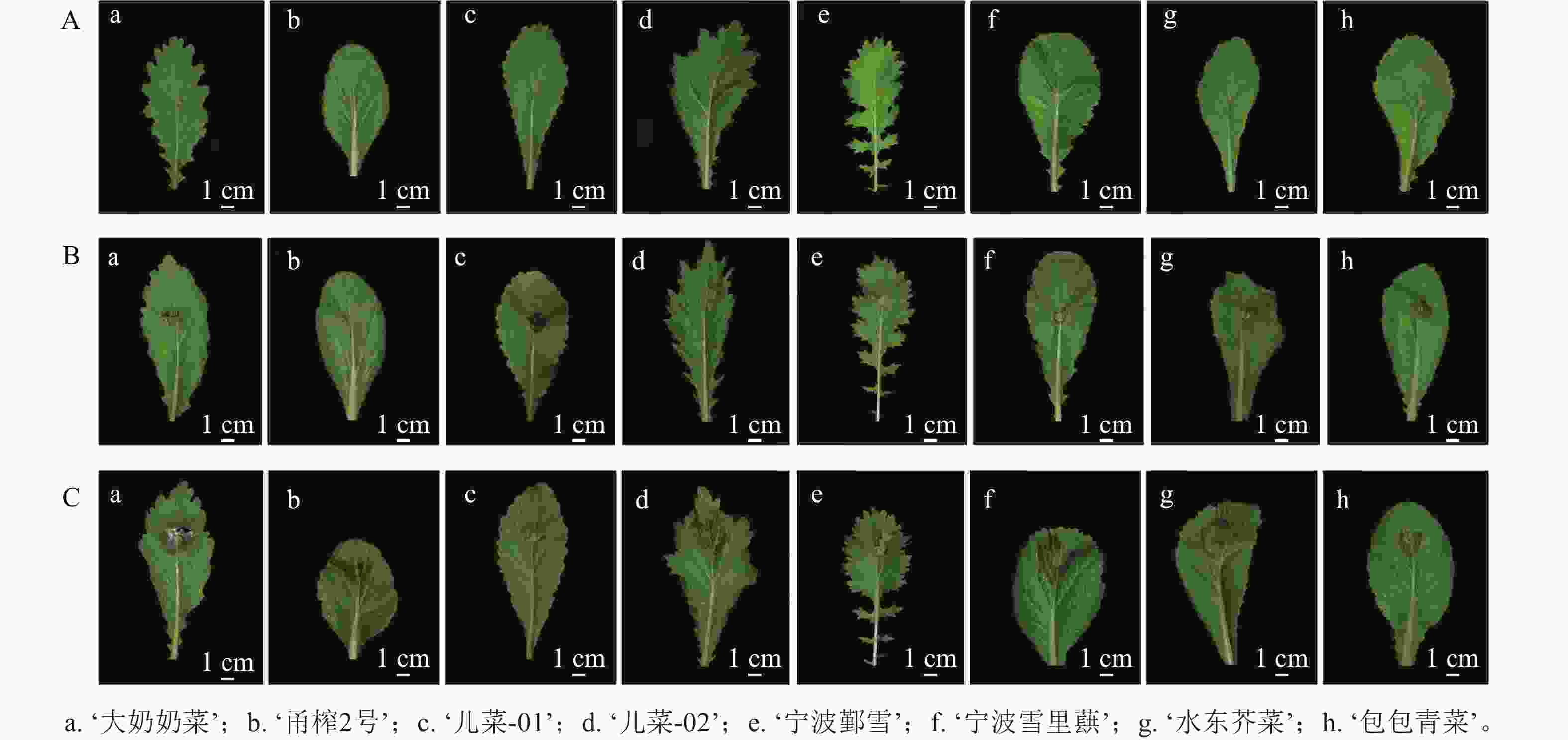

由图2可知:随着接菌时间的延长,8个芥菜品种的菌斑面积均呈现逐渐增大的趋势。在核盘菌侵染12 h后,叶片与菌丝接触的区域开始出现菌斑。随着侵染时间增加至24 h,菌斑逐渐扩大至清晰可见,且与12 h相比,菌斑面积显著增大。至36 h,核盘菌侵染已导致部分叶片出现腐烂现象。

图 2 8个芥菜品种接种核盘菌12 h (A)、24 h (B)、36 h (C)的叶片表型

Figure 2. Phenotypes of 8 mustard cultivars inoculated with S. sclerotiorum at 12 h (A), 24 h (B), and 36 h (C)

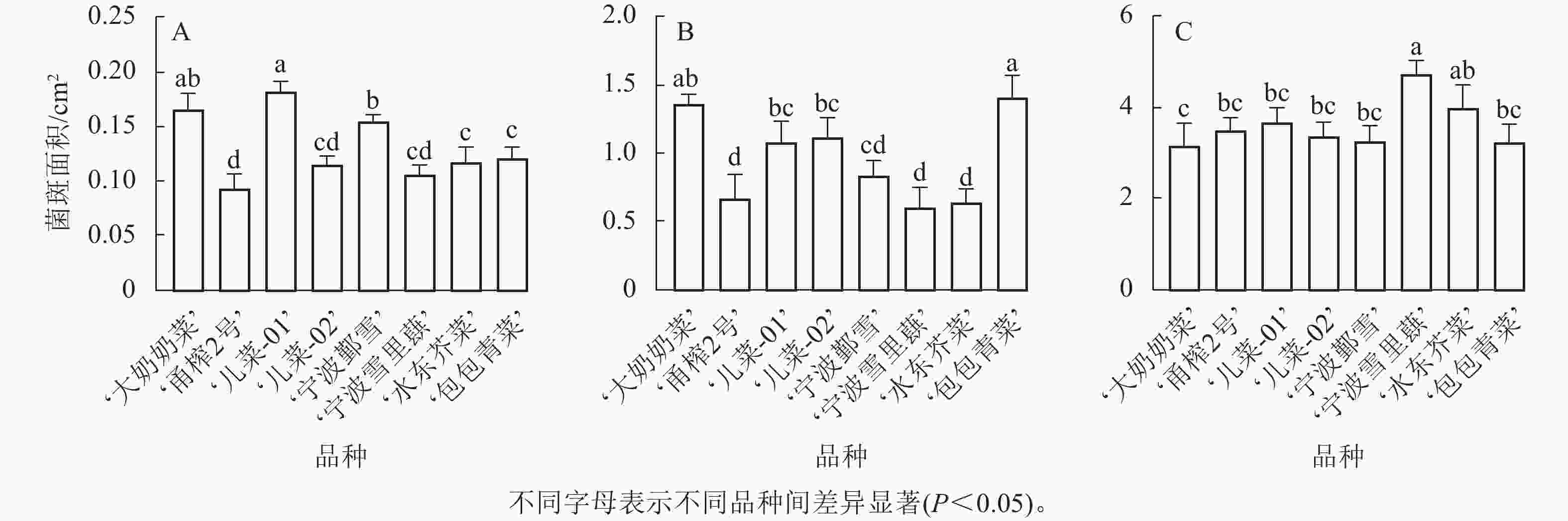

其中,在接种核盘菌12 h时,‘儿菜-01’的菌斑面积最大,‘大奶奶菜’和‘宁波鄞雪’次之,而‘甬榨2号’的菌斑面积最小。‘儿菜-02’‘宁波雪里蕻’‘水东芥菜’和‘包包青菜’的菌斑面积则表现为中间值(图3A)。在接种核盘菌24 h时,‘包包青菜’的菌斑面积增长最为明显,达最大值,除与‘大奶奶菜’以外,与其他品种均差异显著(P<0.05)。‘儿菜-01’和‘儿菜-02’之间无显著差异,‘宁波鄞雪’‘水东芥菜’和‘宁波雪里蕻’的菌斑面积次之,而‘甬榨2号’的菌斑面积仍最小(图3B)。在接种核盘菌36 h时,菌斑面积为3.176~4.758 cm2。此时,‘宁波雪里蕻’的菌斑面积最大,而‘大奶奶菜’的菌斑面积最小,其他品种之间差异不显著(图3C)。因此,8个不同品种的芥菜中,‘甬榨2号’对核盘菌的抗性最强,其次为‘水东芥菜’。

-

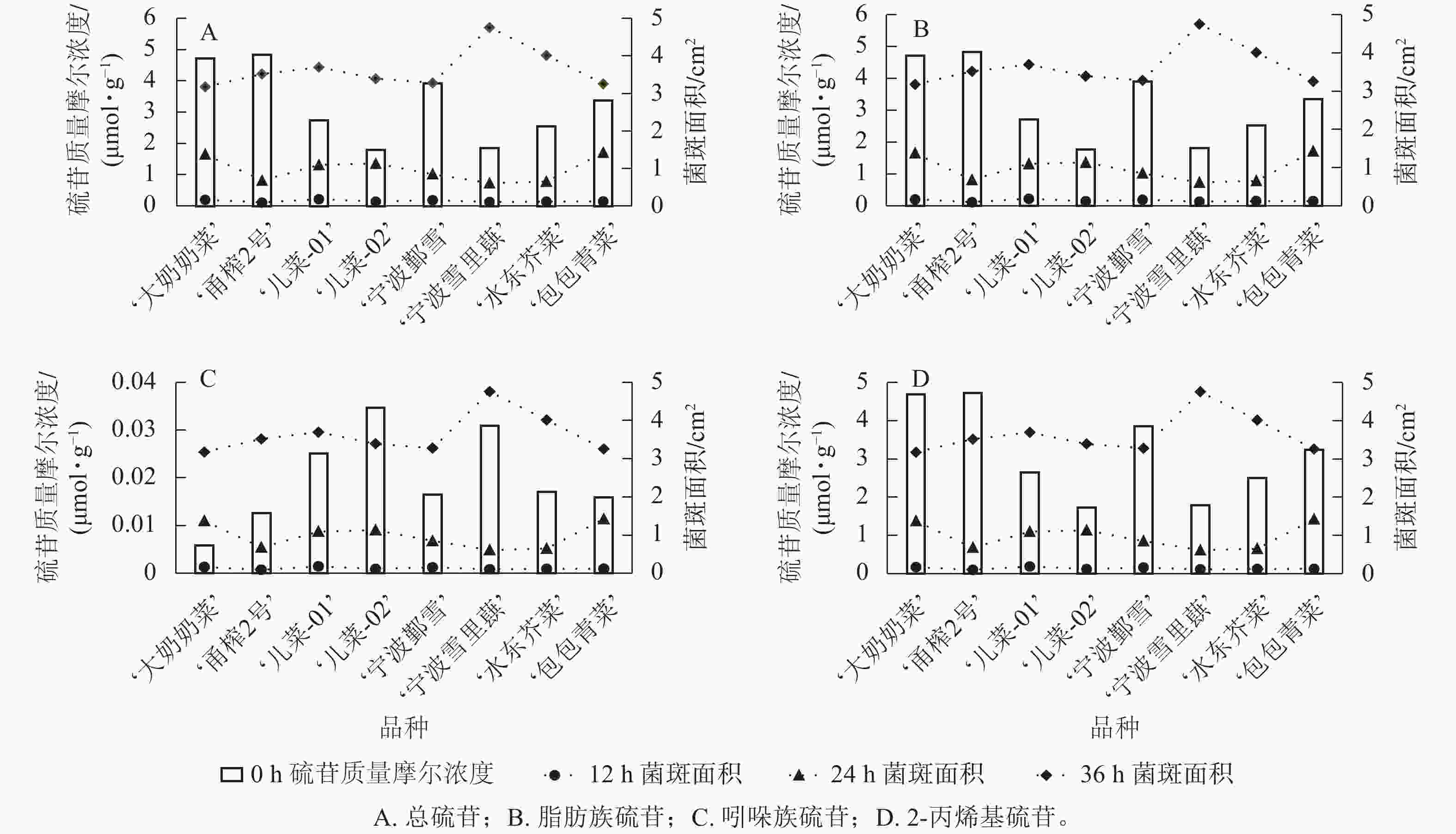

从图4可见:不同芥菜品种的硫苷组分质量摩尔浓度在接种核盘菌后的抗病表现存在差异。总硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高的‘甬榨2号’在接种24 h后表现出最强的抗病性,其叶片菌斑面积最小;而总硫苷质量摩尔浓度较低的‘儿菜-02’则在接种24 h后叶片菌斑面积最大(图4A)。‘儿菜-01’因脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度相对较低,在接种12 h后菌斑面积达最大;相比之下,脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高的‘甬榨2号’在接种12、24 h时的菌斑面积均为最小(图4B)。吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高的‘儿菜-02’和‘宁波雪里蕻’在接种12 h后的菌斑面积与其他品种相比,平均减少21.6%;而吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度最低的‘大奶奶菜’在接种12 h后的菌斑面积最大(图4C)。此外, 2-丙烯基硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高的‘甬榨2号’在接种12、24 h时菌斑面积最小,而2-丙烯基硫苷质量摩尔浓度较低的‘儿菜-02’菌斑面积最大(图4D)。

-

硫苷是十字花科植物的关键防御物质,其降解产物异硫氰酸酯在抵抗虫害及病原微生物入侵过程中发挥了重要作用[24−26]。在本研究的8个芥菜品种中,检测到脂肪族硫苷和吲哚族硫苷2种硫苷类型,其中2-丙烯基硫苷作为脂肪族硫苷的主要成分占总硫苷的95%以上,这与前人研究相符[27]。有研究表明:叶柄宽度、叶柄长度与硫苷质量摩尔浓度分别呈显著正相关和负相关[6]。同一时期、同类型芥菜的硫苷质量摩尔浓度也存在较大差异,如茎用芥菜‘大奶奶菜’的硫苷质量摩尔浓度为4.725 µmol·g−1,而儿菜却只有1.800~2.735 µmol·g−1,这可能是不同品种中硫苷代谢关键基因的差异表达造成的[28]。此外,茎用芥菜整体硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高,叶用芥菜次之,这可能是茎用芥菜的食用部位为茎部,而叶用芥菜主要食用部位为叶片,它们都是经历了长期的人工选育而来,人们倾向于选择硫苷质量摩尔浓度相对较低的品种。因此,人们进行人工选择时,更加关注茎用芥菜的茎部和叶用芥菜的叶片中硫苷质量摩尔浓度相对较低的品种,对非食用器官中硫苷质量摩尔浓度没有选择性的要求,故茎用芥菜的叶片中硫苷质量摩尔浓度整体上高于叶用芥菜。

-

本研究表明:芥菜对核盘菌的抗性与硫苷质量摩尔浓度存在一定关联,但两者并非呈简单的线性关系。不同结构类型的硫苷(如脂肪族、吲哚族硫苷)及其特定组分(如2-丙烯基硫苷)可能在介导抗病反应中发挥着差异化且关键的作用。硫苷被证明可通过植物维管系统的快速运输机制,在病原菌侵染后数小时内完成侵染部位的定向富集[29]。MADLOO等[15]发现羽衣甘蓝中主要防御组分2-丙烯基硫苷的积累水平与菌核病抑制率呈剂量依赖性正相关。本研究也发现:总硫苷和2-丙烯基硫苷质量摩尔浓度较高的‘甬榨2号’在接种12、24 h时菌斑面积最小,这可能是‘甬榨2号’对病原菌侵染的快速响应的原因。ZHANG等[29]研究表明:吲哚族硫苷主要依赖韧皮部运输,运输速度较慢且具有滞后性,但可在植物体内形成系统性分布,为长期防御提供保障。而本研究中,吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度相对较高的‘儿菜-02’和‘宁波雪里蕻’,在核盘菌接种12 h时菌斑面积较小,抑制菌丝扩展,表明质量摩尔浓度较高的吲哚族硫苷可能在病原菌侵染早期通过快速响应机制增强了植物抗性。因此,不同品种芥菜的抗病性不仅取决于其叶片中总硫苷质量摩尔浓度,更与硫苷组分比例及其协同作用密切相关。

-

本研究8个芥菜品种叶片中硫苷质量摩尔浓度为1.851~4.844 µmol·g−1,不同品种之间硫苷质量摩尔浓度存在差异,茎用芥菜硫苷质量摩尔浓度高于叶用芥菜,2-丙烯基硫苷在所有品种中占总硫苷的95%以上,‘甬榨2号’的脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度最高,‘儿菜-02’的吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度最高,‘水东芥菜’各组分硫苷质量摩尔浓度处于中间型;芥菜对病原菌的抗性方面,‘甬榨2号’对核盘菌的抗性最强,其次为‘水东芥菜’。

Identification of glucosinolate content and resistance of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in different mustard cultivars

-

摘要:

目的 对8个芥菜Brassica juncea品种叶片硫苷质量摩尔浓度进行分析,旨在探究硫苷质量摩尔浓度及组分对植株抗病性的作用。 方法 分别以4个茎用芥菜B. juncea var. tumida品种‘大奶奶菜’‘Danainaicai’、‘儿菜-01’‘Ercai-01’、‘儿菜-02’‘Ercai-02’、‘甬榨2号’‘Yongzha No. 2’和4个叶用芥菜B. juncea var. rugosa品种‘宁波鄞雪’‘Ningboyinxue’、‘宁波雪里蕻’‘Ningboxuelihong’、‘水东芥菜’‘Shuidongjiecai’、‘包包青菜’‘Baobaoqingcai’为试材,测定芥菜叶片硫苷质量摩尔浓度,并通过活体接种核盘菌Sclerotinia sclerotiorum测量菌斑面积进行抗病性分析。 结果 不同芥菜品种叶片总硫苷质量摩尔浓度存在差异,总硫苷质量摩尔浓度为1.851~4.844 µmol·g−1,脂肪族硫苷质量摩尔浓度为1.766~4.831 µmol·g−1,两者均为‘甬榨2号’最高,‘儿菜-02’最低;吲哚族硫苷质量摩尔浓度为0.006~0.035 µmol·g−1,‘儿菜-02’最高,‘大奶奶菜’最低;‘水东芥菜’各组分硫苷质量摩尔浓度均处于中间型。2-丙烯基硫苷在所有品种中占总硫苷质量摩尔浓度的95%以上。在12 h时,‘儿菜-01’菌斑面积最大,在24 h时,‘包包青菜’菌斑面积最大,‘甬榨2号’菌斑面积在2个时间点均为最小;在36 h时,‘宁波雪里蕻’菌斑面积最大,‘大奶奶菜’最小(P<0.05)。 结论 芥菜对病原菌的抗性与硫苷总量、组分质量摩尔浓度及其比例密切相关,茎用芥菜总硫苷质量摩尔浓度高于叶用芥菜,‘甬榨2号’对核盘菌的抗性最强,其次为‘水东芥菜’。图4表2参29 Abstract:Objective To systematically analyze the glucosinolate (GSL) content in the leaves of different mustard (Brassica juncea) cultivars, with the aim of investigating the effects of GSL content and composition on plant disease resistance. Method 4 stem mustard cultivars (B. juncea var. tumida), namely ‘Danainaicai’‘Ercai-01’‘Ercai-02’‘Yongzha No.2’, and 4 leaf mustard cultivars (B. juncea var. rugosa), namely ‘Ningboyinxue’‘Ningboxuelihong’‘Shuidongjiecai’‘Baobaoqingcai’, were selected as experimental materials to determine the GSL content in their leaves. Disease resistance was assessed by measuring plaque areas through live inoculation with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Result Significant differences were observed in the total GSL content among the leaves of different mustard cultivars. The total GSL content ranged from 1.851 to 4.844 µmol·g−1, while the aliphatic GSL (AGSL) content varied between 1.766 and 4.831 µmol·g−1. Both the total GSL and AGSL contents were highest in ‘Yongzha No. 2’ and lowest in ‘Ercai-02’. Indole GSL (IGSL) content ranged from 0.006 to 0.035 µmol·g−1, with the highest level in ‘Ercai-02’ and the lowest in ‘Danainaicai’. The GSL content of each component in ‘Shuidongjiecai’ fell into the intermediate range. Sinigrin (SIN) accounted for more than 95% of the total GSL content across all cultivars. At 12 hours post-inoculation, the plaque area of ‘Ercai-01’ was the largest. At 24 hours, the plaque area of ‘Baobaoqingcai’ was the largest, whereas ‘Yongzha No. 2’ exhibited the smallest plaque area at both time points. At 36 hours, ‘Ningboxuelihong’ had the largest plaque area, while ‘Danainaicai’ showed the smallest plaque area (P<0.05). Conclusion The resistance of mustard cultivars to pathogenic bacteria was closely associate with the total amount, component content, and proportion of GSL. Stem mustard cultivars generally exhibited higher GSL content compared to leaf mustard cultivars. Among the test cultivars, ‘Yongzha No. 2’ demonstrated the strongest resistance to the nuclear plate fungus, followed by ‘Shuidongjiecai’. [Ch, 4 fig. 2 tab. 29 ref.] -

表 1 8个芥菜品种的主要生长表型

Table 1. Main growth phenotypes of 8 mustard cultivars

品种 株高/cm 株幅/cm 叶片面积/cm2 ‘大奶奶菜’ 18.131±1.741 a 22.741±1.517 bc 37.178±4.875 ab ‘甬榨2号’ 17.348±1.989 ab 23.475±3.135 bc 22.438±2.809 c ‘儿菜-01’ 14.799±3.317 abc 22.909±1.981 bc 28.962±6.577 bc ‘儿菜-02’ 13.533±3.497 bcd 19.066±1.387 c 30.529±6.337 bc ‘宁波鄞雪’ 13.373±1.626 bcd 24.567±3.755 ab 24.244±3.119 c ‘宁波雪里蕻’ 9.857±1.876 d 26.671±3.487 ab 31.790±2.606 bc ‘水东芥菜’ 12.635±1.688 cd 29.030±3.728 a 28.858±5.951 bc ‘包包青菜’ 10.121±0.594 d 24.919±1.507 ab 41.555±6.464 a 说明:不同字母表示同一指标不同品种间差异显著(P<0.05)。 表 2 8个芥菜品种的硫苷组分质量摩尔浓度

Table 2. Glucosinolate component contents in 8 mustard cultivars

品种 总硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 脂肪族硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 吲哚族硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 2-丙烯基硫苷/(µmol·g−1) 2-丙烯基硫苷/总硫苷/% ‘大奶奶菜’ 4.725±0.615 ab 4.719±0.614 ab 0.006±0.001 c 4.690±0.623 a 99.26 ‘甬榨2号’ 4.845±0.593 a 4.831±0.593 a 0.013±0.003 de 4.732±0.562 a 97.70 ‘儿菜-01’ 2.735±0.256 de 2.710±0.257 de 0.025±0.003 b 2.648±0.234 cd 96.79 ‘儿菜-02’ 1.800±0.335 f 1.766±0.336 f 0.035±0.002 a 1.728±0.324 e 95.95 ‘宁波鄞雪’ 3.915±0.433 bc 3.899± 0.434 bc0.017±0.002 cd 3.861±0.427 ab 98.61 ‘宁波雪里蕻’ 1.851±0.617 ef 1.820±0.616 ef 0.031±0.002 a 1.793±0.601 de 96.86 ‘水东芥菜’ 2.549±0.310 def 2.532±0.311 def 0.017±0.003 c 2.507±0.312 cde 98.34 ‘包包青菜’ 3.376±0.292 cd 3.360±0.290 cd 0.016±0.002 cd 3.236±0.286 bc 95.88 说明:不同字母表示同一指标不同品种间差异显著(P<0.05)。 -

[1] AGERBIRK N, OLSEN C E, NIELSEN J K. Seasonal variation in leaf glucosinolates and insect resistance in two types of Barbarea vulgaris ssp. arcuata[J]. Phytochemistry, 2001, 58(1): 91−100. DOI: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00151-0. [2] XU Deyang, SANDEN N C H, HANSEN L L, et al. Export of defensive glucosinolates is key for their accumulation in seeds[J]. Nature, 2023, 617(7959): 132−138. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05969-x. [3] LAFARGA T, BOBO G, VIÑAS I, et al. Effects of thermal and non-thermal processing of cruciferous vegetables on glucosinolates and its derived forms[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2018, 55(6): 1973−1981. DOI: 10.1007/s13197-018-3153-7. [4] CAVÒ E, TAVIANO M F, DAVÌ F, et al. Phenolic and volatile composition and antioxidant properties of the leaf extract of Brassica fruticulosa subsp. fruticulosa (Brassicaceae) growing wild in Sicily (Italy)[J]. Molecules, 2022, 27(9): 2768. DOI: 10.3390/molecules27092768. [5] WANG Jinglei, QIU Yang, WANG Xiaowu, et al. Insights into the species-specific metabolic engineering of glucosinolates in radish (Raphanus sativus L. ) based on comparative genomic analysis[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 16040. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-16306-4. [6] ASSEFA A D, KIM S H, KO H C, et al. Leaf mustard (Brassica juncea) germplasm resources showed diverse characteristics in agro-morphological traits and glucosinolate levels[J]. Foods, 2023, 12(23): 4374. DOI: 10.3390/foods12234374. [7] MALHOTRA B, KUMAR P, BISHT N C. Defense versus growth trade-offs: insights from glucosinolates and their catabolites[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2023, 46(10): 2964−2984. DOI: 10.1111/pce.14462. [8] AGERBIRK N, OLSEN C E. Glucosinolate structures in evolution[J]. Phytochemistry, 2012, 77: 16−45. DOI: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.02.005. [9] 陈彩霞, 王泽昊, FENG Jie, 等. 植物病原真菌的菌核研究进展[J]. 微生物学通报, 2018, 45(12): 2762−2768. CHEN Caixia, WANG Zehao, FENG Jie, et al. Sclerotia of plant pathogenic fungi[J]. Microbiology China, 2018, 45(12): 2762−2768. DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180117. CHEN Caixia, WANG Zehao, FENG Jie, et al. Sclerotia of plant pathogenic fungi[J]. Microbiology China, 2018, 45(12): 2762−2768. DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180117. [10] 孙叶烁, 郝玲玉, 张杰, 等. 大白菜菌核病抗性鉴定方法研究[J]. 西北农林科技大学学报(自然科学版), 2019, 47(12): 123−129. SUN Yeshuo, HAO Lingyu, ZHANG Jie, et al. Identification method of resistance to Sclerotinia in Chinese cabbage[J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University (Natural Science Edition), 2019, 47(12): 123−129. DOI: 10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2019.12.015. SUN Yeshuo, HAO Lingyu, ZHANG Jie, et al. Identification method of resistance to Sclerotinia in Chinese cabbage[J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University (Natural Science Edition), 2019, 47(12): 123−129. DOI: 10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2019.12.015 .[11] CHEN Rongshi, WANG Jiyi, SARWAR R, et al. Genetic breakthroughs in the Brassica napus-Sclerotinia sclerotiorum interactions[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023, 14: 1276055. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1276055. [12] ZHU Biao, LIANG Zhile, ZANG Yunxiang, et al. Diversity of glucosinolates among common Brassicaceae vegetables in China[J]. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2023, 9(3): 365−380. DOI: 10.1016/j.hpj.2022.08.006. [13] CHHAJED S, MOSTAFA I, HE Yan, et al. Glucosinolate biosynthesis and the glucosinolate-myrosinase system in plant defense[J]. Agronomy, 2020, 10(11): 1786. DOI: 10.3390/agronomy10111786. [14] STOTZ H U, SAWADA Y, SHIMADA Y, et al. Role of camalexin, indole glucosinolates, and side chain modification of glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates in defense of Arabidopsis against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum[J]. The Plant Journal, 2011, 67(1): 81−93. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04578.x. [15] MADLOO P, LEMA M, FRANCISCO M, et al. Role of major glucosinolates in the defense of kale against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris[J]. Phytopathology, 2019, 109(7): 1246−1256. DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-18-0340-R. [16] MANN A, KUMARI J, KUMAR R, et al. Targeted editing of multiple homologues of GTR1 and GTR2 genes provides the ideal low-seed, high-leaf glucosinolate oilseed mustard with uncompromised defence and yield[J]. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 2023, 21(11): 2182−2195. DOI: 10.1111/pbi.14121. [17] PARITOSH K, YADAVA S K, SINGH P, et al. A chromosome-scale assembly of allotetraploid Brassica juncea (AABB) elucidates comparative architecture of the A and B genomes[J]. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 2021, 19(3): 602−614. DOI: 10.1111/pbi.13492. [18] KANG Lei, QIAN Lunwen, ZHENG Ming, et al. Genomic insights into the origin, domestication and diversification of Brassica juncea[J]. Nature Genetics, 2021, 53(9): 1392−1402. DOI: 10.1038/s41588-021-00922-y. [19] SINGH K P, KUMARI P, RAI P K. Current status of the disease-resistant gene(s)/QTLs, and strategies for improvement in Brassica juncea[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2021, 12: 617405. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2021.617405. [20] 刘琳, 李珊珊, 袁仁文, 等. 芥菜主要化学成分及生物活性研究进展[J]. 北方园艺, 2018(15): 180−185. LIU Lin, LI Shanshan, YUAN Renwen, et al. A review of main chemical composition and biological activities of Brassica juncea (L. ) Czern et Coss[J]. Northern Horticulture, 2018(15): 180−185. DOI: 10.11937/bfyy.20174453. LIU Lin, LI Shanshan, YUAN Renwen, et al. A review of main chemical composition and biological activities of Brassica juncea (L. ) Czern et Coss[J]. Northern Horticulture, 2018(15): 180−185. DOI: 10.11937/bfyy.20174453 .[21] SUN Bo, LIU Na, ZHAO Yanting, et al. Variation of glucosinolates in three edible parts of Chinese kale (Brassica alboglabra Bailey) varieties[J]. Food Chemistry, 2011, 124(3): 941−947. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.07.031. [22] CAI Congxi, YUAN Wenxin, MIAO Huiying, et al. Functional characterization of BoaMYB51s as central regulators of indole glucosinolate biosynthesis in Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra Bailey[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2018, 9: 1599. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01599. [23] GUO Rongfang, SHEN Wangshu, QIAN Hongmei, et al. Jasmonic acid and glucose synergistically modulate the accumulation of glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2013, 64(18): 5707−5719. DOI: 10.1093/jxb/ert348. [24] HARUN S, ABDULLAH-ZAWAWI M R, GOH H H, et al. A comprehensive gene inventory for glucosinolate biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(28): 7281−7297. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01916. [25] 郝娇娇, 马永华, 陆彦池, 等. 硫苷介导的白菜抵御甜菜夜蛾幼虫取食胁迫的分子机制[J]. 浙江农林大学学报, 2023, 40(1): 81−88. HAO Jiaojiao, MA Yonghua, LU Yanchi, et al. Molecular mechanism of glucosinolate-mediated Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis against feeding stress of Spodoptera exigua larvae[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2023, 40(1): 81−88. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220172. HAO Jiaojiao, MA Yonghua, LU Yanchi, et al. Molecular mechanism of glucosinolate-mediated Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis against feeding stress of Spodoptera exigua larvae[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2023, 40(1): 81−88. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220172 .[26] 刘梦婷, 梅源, 刘佳琦, 等. 硫苷及其代谢产物对十字花科蔬菜风味形成的作用研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2024, 45(23): 349−357. LIU Mengting, MEI Yuan, LIU Jiaqi, et al. Research progress on the role of glucosinolates and their metabolites for the flavor formation in cruciferous vegetables[J]. Food Science, 2024, 45(23): 349−357. DOI: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20240412-108. LIU Mengting, MEI Yuan, LIU Jiaqi, et al. Research progress on the role of glucosinolates and their metabolites for the flavor formation in cruciferous vegetables[J]. Food Science, 2024, 45(23): 349−357. DOI: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20240412-108 .[27] XIA Rui, XU Liai, HAO Jiaojiao, et al. Transcriptome dynamics of Brassica juncea leaves in response to omnivorous beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua, Hübner)[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(23): 16690. DOI: 10.3390/ijms242316690. [28] 丁云花, 何洪巨, 宋曙辉, 等. 不同西兰花品种中硫代葡萄糖苷的组分与含量分析[J]. 长江蔬菜, 2015(20): 70−73, 74. DING Yunhua, HE Hongju, SONG Shuhui, et al. Glucosinolate component and content analysis of different broccoli varieties[J]. Journal of Changjiang Vegetables, 2015(20): 70−73, 74. DOI: 10.3865/j.issn.1001-3547.2015.20.027. DING Yunhua, HE Hongju, SONG Shuhui, et al. Glucosinolate component and content analysis of different broccoli varieties[J]. Journal of Changjiang Vegetables, 2015(20): 70−73, 74. DOI: 10.3865/j.issn.1001-3547.2015.20.027 .[29] ZHANG Yuanyuan, YANG Zhiquan, HE Yizhou, et al. Structural variation reshapes population gene expression and trait variation in 2, 105 Brassica napus accessions[J]. Nature Genetics, 2024, 56(11): 2538−2550. DOI: 10.1038/s41588-024-01957-7. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250273

下载:

下载: