-

无论是脊椎动物还是无脊椎动物,先天性免疫都是第一线防御机制,对抗着各类病原体的侵染。吞噬作用作为一种高度保守进程的先天性免疫机制,能够为许多细胞用来消化微生物病原体以及凋亡或坏死的细胞残骸[1-3]。在吞噬作用中,外来物质被细胞识别并结合到细胞表面,被吞噬小体吞入,并在被吞入的物质周围形成细胞器[4]。吞噬小体经过裂变以及与核内体、溶酶体,或是两者共同的限制性融合后形成成熟的吞噬溶酶体。进入吞噬溶酶体内部的病原体则被低pH值、水解作用以及自由基所消灭[5]。黑腹果蝇Drosophila melanogaster是最常见的果蝇,因拥有与哺乳动物相近的先天性免疫系统,而被认为是研究宿主与微生物相互作用的最佳基因模式生物[6-7]。近年来,果蝇Schneider细胞株(S2)细胞已被确认是一种非常适合研究细胞感染的宿主模型,在对抗衣原体Chlamydia,单胞增生性李斯特菌Listeria monocytogenes,查菲埃立克体Ehrlichia chaffeensis,白念珠菌Candida albicans,大肠埃希菌Escherichia coli以及金黄葡萄球菌Staphylococcus aureus等病菌[6, 8-14]的体外感染过程中,S2细胞与哺乳动物巨噬细胞的作用机制非常相近。金黄葡萄球菌是一种主要的人类病原体,致病率显著,研究显示金黄葡萄球菌可能是一种兼性胞内病原体[15],并认为金黄葡萄球菌可以在巨噬细胞中存活数日而不影响细胞的生存情况[16]。笔者就果蝇S2细胞对热灭活大肠埃希菌(heat inactivated Esherichia coli, HIEC)及热灭活金黄葡萄球菌(heat inactivated Staphylococcus aureus, HISA)的吞噬模式展开研究,揭示了在S2细胞对抗革兰氏阳性菌时,吞噬作用在清除该类病原体时所起到的重要作用以及金黄葡萄球菌抑制消化过程从而抵御细胞吞噬的策略。

HTML

-

黑腹果蝇S2细胞株从初代培养24 h的胚胎中分离获得,在体积分数为10%的小牛血清的果蝇培养基(Ivitrogen, 美国)中28 ℃培养[17]。为了确认脂多糖(LPS,Sigma,美国)或聚肽糖(PG,Sigma,美国)的活化作用是否会增强吞噬作用,将S2细胞以106个·孔-1铺开在6孔板中并粘附30 min,LPS或PG经超声处理1 h后,按1.0 mg·L-1的剂量加入到每个孔中孵育1 h,备用。

大肠埃希菌ATCC 14948菌株在LURIA-BERTANI培养基(LB)37 ℃培养24 h后,10 000 g离心10 min收集细菌。金黄葡萄球菌ATCC 25923菌株在含20.0 g·L-1氯化钠的哥伦比亚培养基中培养过夜,在盐溶液中重悬。热灭活大肠埃希菌(HIEC)或热灭活金黄葡萄球菌(HISA)以5×109个·L-1的密度接种于S2细胞,28 ℃孵育1 h。不同时间段收集S2细胞分析。

-

收集感染后的果蝇S2细胞(5.0~10.0 μL),在含体积分数2%多聚甲醛与2%戊二醛的0.1 mol·L-1二甲砷酸钠缓冲液(pH 7.4)固定剂中浸泡16 h,室温下不断旋转。以0.1 mol·L-1二钾砷酸钠缓冲液清洗,3次·样品-1,5 min·次-1,保持室温下旋转。随后加入体积分数2%锇(Osmium),并以0.1 mol·L-1二钾砷酸钠缓冲液清洗3次,5 min·次-1,保持室温下旋转。样品固定,20.0 g·L-1醋酸双氧铀缓冲液(pH 5.2)进行染色,室温避光染色1 h,保持旋转,随后以0.1 mol·L-1二钾砷酸钠缓冲液清洗3次,5 min·次-1并不断旋转。通过逐级增加的丙酮溶液(体积分数依次为50%,60%,70%,80%,90%,95%,100%)对样品进行脱水,室温下旋转处理,随后在100%环氧丙烯中毒处理10 min。以EMBED 812或502树脂黏结剂进行最终的渗透处理,V(环氧丙烯):V(黏合剂)=1:1,室温旋转处理10 min;V(环氧丙烯):V(黏合剂)=1:2,室温旋转处理20 min;100%黏合剂处理10 min。最终,样品中加入新的100%黏合剂,渗透16 h后,在干燥烘箱中以60 ℃聚合24 ~ 48 h。Hitachi 7650透射电镜(Hitachi, 日本)在70 kV下采集图像[10]。

-

果蝇S2细胞用体积分数10%胎牛血清(FBS)的施耐德培养基12孔板中铺板培养,并将密度为5×109个·L-1异硫氰酸荧光素标记(FITC,Invitrogen, 美国)的热灭活大肠埃希菌(HIEC)/热灭活金黄葡萄球菌(HISA),加入到S2细胞中28 ℃共培养1 h。以磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)清洗后,将混合细胞移植到多聚赖氨酸预处理的载玻片(Sigma,美国)上固定。之后,分别使用罗丹明鬼笔环肽(Invitrogen, 美国)和4′, 6-二脒基-2-苯基吲哚(DAPI,Sigma,美国)一同孵育,用以标记肌动蛋白或细胞核DNA[18]。

-

细胞培养与处理见1.2.2节。果蝇S2细胞接种细菌后,以PBS清洗,将混合细胞收集到流式管中,通过流式细胞仪检测S2细胞内的FITC荧光信号,统计S2细胞对HIEC和HISA的吞噬能力。为了研究细胞的吞噬作用对活细菌和热灭活细菌的敏感度,以胞内有1个以上FITC标记细菌的细胞在所有细胞中所占的百分比为参考值来予以评价。

-

在果蝇S2细胞(培养方法见1.2.2节)中加入LPS或PG,孵育S2细胞1 h,从而激活S2细胞;激活后的S2细胞以1×109个·L-1在6孔板中铺开,分别接种pHrodo标记的灭活病原菌(5×109个·L-1),28 ℃共孵育1 h。收集混合细胞,立刻在共聚焦显微镜下观察。分别统计不同处理组中,吞入pHrodo标记病原菌的S2细胞在全部细胞中所占百分比[18]。不同处理组间的差异以t检验进行统计学分析,P < 0.05为显著。

-

果蝇S2细胞经过不同实验处理后,以PBS清洗,收集细胞,使用Trizol试剂(Invitrogen,美国)提取总RNA,操作步骤依据产品使用说明书[18]。即刻使用5.0 μg总核糖核酸,以M-MLV反转录酶(Takara,日本)合成为20.0 μL cDNA。实时荧光定量的检测采用基因特异引物与TaqMan探针(表 1),反应体系包括10.0 μL Premix Ex Taq(Takara,日本),1.0 μL cDNA样品,7.2 μL无酶水,各基因对应TaqMan探针0.3 μL,以及各特异性引物0.4 μL。聚合酶链式反应(PCR)程序如下:95 ℃,30 s;90 ℃,5 s,60 ℃,30 s,循环50次。数据分析使用iQTM5软件。

寡核苷酸探针 引物与探针序列 RP49-F 5'-CCGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATCTG-3' RP49-R 5'-CACGTTGTGCACCAGGAACTT-3' Rp49-探针 FAM-GGCAGCATGTGGCGGGTGCGCTT-Edipse Rel-F 5'-GCCAGAAAAACCCGTGAGTC-3' Rel-R 5'-AGGTACTTCCCCGATGTTCG-3' Rel-探针 FAM-CGACGTGGCCGCCGCAGA-Edipse Def-F 5'-CCACATGCGACCTACTCTCCA-3' Def-R 5'-AGCCGCCTTTGAACCCCT-3' Def-探针 FAM-ACCACACCGCCTGCGCCG-Eclipse Drs-F 5'-CTGGTGGTCCTGGGAGCC-3' Drs-R 5, -AGCGTCCCTCCTCCTTGC-3' Drs-探针 FAM-CCGATGCCGACTGCCTGTCC-Eclipse Table 1. Primers and TaqMan probe sequences in qRT-PCR

-

本研究中每组试验均使用3个生物学重复。统计学显著性分析使用t检验,判断对照组与实验组的差异性,P < 0.05为显著,P < 0.01为极显著。

1.1. 试验材料

1.2. 试验方法

1.2.1. 样品制备与透射电子显微镜(TEM)分析

1.2.2. 激光共聚焦显微镜分析

1.2.3. 流式细胞仪检测分析

1.2.4. 细胞酸性指示剂(pHrodo)标签检测溶酶体酸化

1.2.5. 实时荧光定量PCR检测

1.2.6. 统计学分析

-

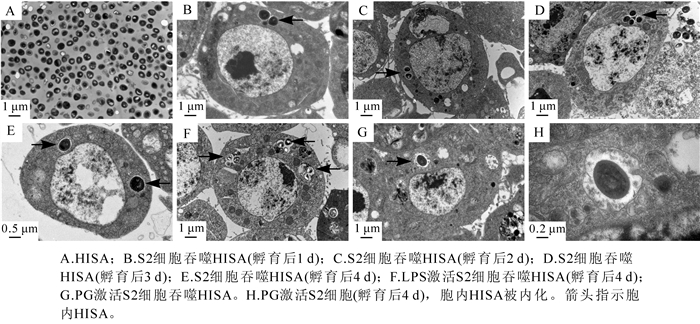

透射电镜下观察黑腹果蝇S2细胞对灭活大肠杆菌(HIEC)或灭活金黄葡萄球菌(HISA)的吞噬过程,发现孵育1 h后S2细胞即可顺利吞噬HIEC(图 1A),孵育后第1天S2细胞内HIEC已消失(图 1B);但共孵育1 h后S2细胞未能吞噬HISA(图 1C),HISA(图 2A)与S2细胞共孵育4 d,仍保持形态完整(图 1D,图 2B,图 2C,图 2D,图 2E)。在PG或LPS激活后,S2细胞也不能有效地吞噬HISA(图 2F,图 2G,图 2H)。与健康的S2细胞相比,在接种后第4天,S2细胞吞入的HISA依然形态完整(图 2E,图 2F,图 2G,图 2H);吞入HISA的S2细胞没有出现凋亡或破裂,表明细胞内的HISA并没有对S2细胞造成明显的损伤。

-

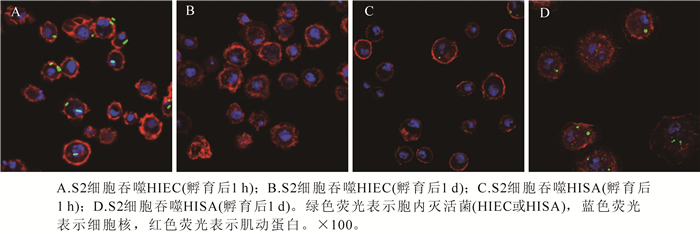

激光共聚焦显微观察发现,在S2细胞吞噬热灭活大肠杆菌HIEC 1 h后,胞内可观察到HIEC发出的绿色荧光(图 3A);吞噬发生1 d后,S2细胞内观察不到绿色荧光粒子(图 3B);表明HIEC已经被S2细胞清除。同样处理下,热灭活金黄葡萄球菌HISA没有被S2细胞清除。由图 3C和图 3D可知,HISA被吞噬后,被S2细胞内化到细胞内继续存在。由此可知,在S2细胞接种灭活菌后,HIEC与HISA均被S2细胞吞入,但HIEC被S2细胞清除,而HISA则没有被清除。

-

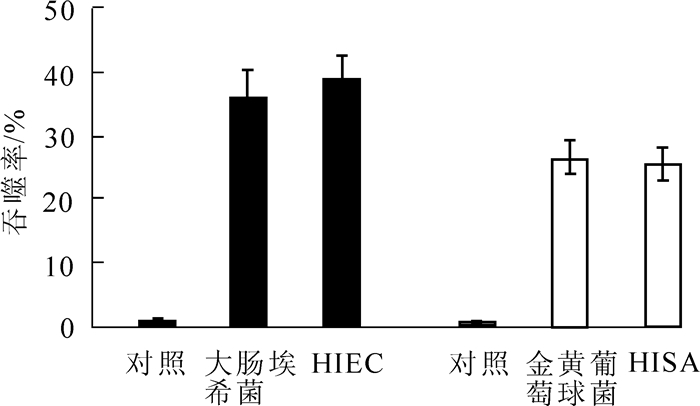

流式细胞仪的检测结果由图 4可知:接种1 h后,吞入了至少1个HIEC粒子的S2细胞在所有S2细胞中所占的比例接近40%,与S2细胞吞噬大肠埃希菌的结果相近;吞入至少1个HISA粒子的S2细胞在所有S2细胞中所占的比例接近25%,与S2细胞吞噬金黄葡萄球菌的结果相近。说明S2细胞吞入活细菌和热灭活细菌的敏感度并没有显著差异。

-

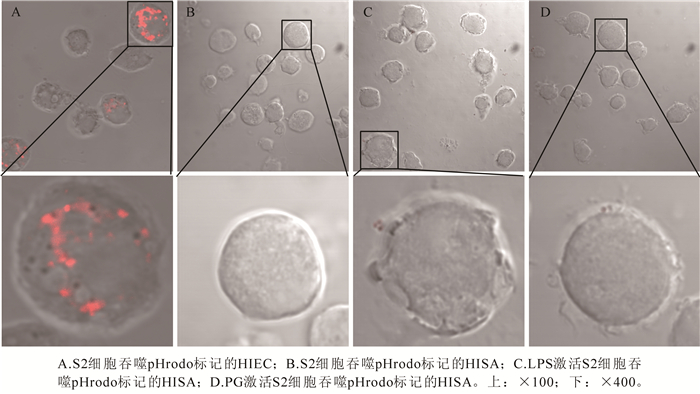

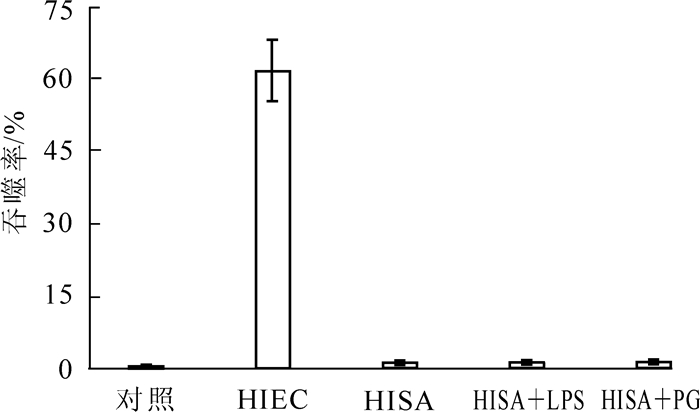

细胞内的酸性环境可诱导pHrodo标记的病原菌激发出红色荧光,从而指示吞噬溶酶体的形成。激光共聚焦显微镜观察发现,接种HIEC 1 h后,S2细胞内可观察到红色荧光,表明S2细胞对HIEC的消化程序被激活,细胞内形成了酸性环境(图 5A);图 5B中未能观察到红色荧光,表明HISA未能激活S2细胞的酸化过程。使用LPS或PG激活S2细胞,再进行接种观察,可发现在接种HISA 1 h后,未能观察到红色荧光,说明S2细胞的酸化过程仍未被激活。

Figure 5. Confocal microscopy of phagocytosis of pHrodo-labeled HIEC or HISA by S2 cells at 1 h post-inoculation

为揭示LPS或PG的刺激对S2细胞吞噬活性的影响,用共聚焦显微镜观察S2细胞吞噬pHrodo标记菌并统计吞噬率。结果表明:共孵育1 h后,只有接种HIEC的S2细胞内呈现酸性环境,其他的处理均不能诱导S2细胞酸化(图 6)。检测吞噬百分比发现,只有HIEC处理组的吞噬率显著高于对照组(P < 0.01)。使用LPS或PG激活S2细胞后再接种,S2细胞对HISA的吞噬率仍没有显著增加。这表明溶酶体酸化过程只发生在S2细胞吞噬HIEC的过程中,而LPS或PG刺激并不能诱导S2细胞吞噬HISA后的酸化过程(图 6)。

-

实时荧光定量PCR反应中引物与TaqMan探针序列如表 1所示。通过实时荧光定量PCR检测不同处理条件下S2细胞内的防御素(defensin),抗真菌肽(drosomycin)和Relish的表达量变化。结果发现:防御素的表达量在HISA,HISA+LPS和HISA+PG等3个处理组中,均发生显著上调(P < 0.01);抗真菌肽的表达量仅在HISA+PG处理组中发生显著上调(P < 0.01)(图 7);Relish的表达量在HIEC处理组中发生显著上调(P < 0.01),但在HISA处理组中无显著变化。

2.1. 透射电镜观察黑腹果蝇S2细胞对HIEC或HISA的吞噬作用

2.2. 激光共聚焦显微观察黑腹果蝇S2细胞对HIEC或HISA的吞噬作用

2.3. 流式细胞仪检测S2细胞对HIEC或HISA的吞噬作用

2.4. 吞噬溶酶体酸化观察和吞噬率检测结果

2.5. 实时荧光定量PCR检测基因表达

-

吞噬作用是动物对抗微生物病原体的一种重要免疫防御机制,由吞噬细胞来执行具体的功能[19-20]。本研究对黑腹果蝇S2细胞吞噬热灭活大肠埃希菌(HIEC)和金黄葡萄球菌(HISA)的异同进行了研究。结果表明:S2细胞能够在接种后1 d有效吞噬并清除HIEC,但却无法清除HISA;即使到了接种后4 d,S2细胞仍不能有效地清除HISA,而是任由它存在于细胞内。经PG或LPS诱导激活的S2细胞同样不能有效地清除HISA。与健康的S2细胞相比,存在于细胞内的HISA在接种4 d后并没有明显破坏S2细胞。许多研究证明在细胞培养模式下,金黄葡萄球菌能够逃逸宿主细胞的免疫系统,具有隐藏的潜能[21],可在胞内坚持存活一段时间[22-23]。在本研究中,热灭活金黄葡萄球菌存在于S2细胞中达4 d以上,说明灭活后的金黄葡萄球菌仍存在抗吞噬的成分,这与金黄葡萄球菌存在多个抗吞噬因子有关[24-26]。统计细胞吞噬率发现,热灭活并不会影响吞噬作用对灭活细菌的敏感性,这一点已被另一项研究所证实[11]。

在消化进程中,吞噬溶酶体的pH值降低,细胞内环境酸化,可帮助吞噬作用的进行,并能够通过pHrodo染料的使用进行检测[27]。LPS是革兰氏阴性菌的主要的细胞膜成分,可以通过Imd(immune deficiency)免疫信号通路激活巨噬细胞;PG是革兰氏阳性菌细胞壁上的主要成分,可以通过Toll信号通路激活巨噬细胞。使用LPS或PG刺激接种HISA的S2细胞,细胞并未形成酸化环境。通过透射电镜与激光共聚焦显微镜的观察,明确了即使S2细胞经过LPS或PG的激活也不能有效地吞噬HISA的结果;检测S2细胞对pHrodo标记的病原菌的吞噬百分比也表明,吞噬溶酶体的酸化只发生在S2细胞对HIEC的吞噬过程中,其他处理并不能引起S2细胞的酸化。

黑腹果蝇S2细胞的吞噬作用中包括了Toll与Imd等2条信号通路,其中Toll通路参与到抗革兰氏阳性菌的免疫作用中,该免疫应答机制中包含Defensin基因[28-29]的表达,而已知的防御素(defensin)是一类由小胱甘酸富集而成,可被诱导的抗微生物肽,有利于宿主对真菌的防御应答[30];Drosomycin基因表达的Drosomycin是一类可诱导的抗真菌肽,同样由Toll通路调节,并在全身脂肪体中均有表达[31-32]。观察发现防御素的表达量在HISA,HISA+LPS以及HISA+PG处理中,均发生显著上调;抗真菌肽的表达量在HISA+PG处理中显著上调;由此可以推断,Toll通路在HISA+PG的刺激下被激活。但是也看到PG虽然能激活S2细胞的Toll通路,但却无法有效清除HISA,同样,胞内的HISA也不会诱导S2细胞凋亡。由此可知,金黄葡萄球菌作为一种人类病原体,对黑腹果蝇来说也是高致病的病原,与其他革兰氏阳性菌相比,它表现出了更强的对防御素的抵御能力[36]。在黑腹果蝇中,Imd通路调节着对革兰氏阴性菌的免疫应答,Relish作为NF-κB通路的转录因子,是Imd通路的终极目标[28]。本研究结果发现:Relish在HIEC处理中显著上调(P < 0.01),说明Imd通路在HIEC处理中被激活,而激活的Imd通路最终诱导S2细胞吞噬HIEC,说明Relish的表达量与S2细胞吞噬HIEC的百分率呈正相关。

有研究表明:金黄葡萄球菌能够迅速地逃避溶酶体/吞噬体的捕获,在细胞液泡内存活可长达4 d,之后逃入细胞质中[16, 37-38]。有趣的是,我们发现灭活金黄葡萄球菌同样能够在S2细胞内存活4 d,其细胞表面物质具有抗吞噬消化的活性。该结果同时暗示着无脊椎动物吞噬细胞对清除部分革兰氏阴性及革兰氏阳性菌均有所帮助,但细胞免疫对这些胞内细菌的清除效力胜于体液免疫。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: