-

森林是陆地生态系统的重要组分部分,土壤有机碳(SOC)储量远高于植被和大气总碳,是全球生态系统碳循环中的活跃碳库,对维持全球碳平衡发挥着不可忽视的作用[1]。全球森林土壤有机碳的微小变化亦会对大气二氧化碳(CO2)变化产生实质影响[2]。根据有机碳的稳定性和分解速率差异可将土壤有机碳分为惰性有机碳、缓效性有机碳和活性有机碳[3]。土壤活性有机碳如易氧化碳(ROC)、颗粒有机碳(POC)等,具有活跃性较高、易被微生物氧化和分解、移动快等特点[4],能显著影响土壤中化学物质的溶解、吸附、吸收、解吸、迁移等,对植物养分供应有最直接的作用[5]。活性有机碳库中,微生物生物量碳(MBC)等对土壤管理、森林经营措施的响应更敏感,是土壤质量的重要指示指标[6]。森林生态系统复杂性高,不同森林类型及同一类型中的不同树种组成、不同演替阶段的土壤有机碳及其活性组分特征亦有明显差异,同时也存在同一林分土壤有机碳随土层深度增加有效性降低的规律[7]。值得注意的是土壤有机碳各组分间能够相互转化,不同组分间又共同调控土壤碳库平衡、碳循环过程,影响和指示森林土壤质量[8]。因此,厘清同一优势树种下不同演替阶段林分或管理措施对森林土壤有机碳活性组分分布积累的影响及其内在机制,对于准确评估土壤质量及碳库动态变化具有重要意义。

松材线虫Bursaphelenchus xylophilus病是一种主要危害马尾松Pinus massoniana林分的毁灭性森林病害。中国感染该病的松林面积已超过180万hm2[9]。马尾松林为南方低山丘陵区群落演替的主要先锋林分,浙江省的松林面积约占全省森林总面积的54.87%。2023年浙江省秋季普查发现:已遭受松材线虫病危害的松林面积约28.72万hm2,病死木达153.2万株[10−11]。当前松材线虫病病害林分的主要清理方式为卫生伐疫木,采伐后出现的林窗空地则让其自然恢复形成马尾松次生林[12]。由于对不同病害程度马尾松林分采伐强度不一致,所以不同采伐强度下自然恢复后的植被类型、组成及林分格局会有很大差异[13]。究其原因为不同采伐强度会导致不同大小的林木生长空间,缓解被伐疫木周围活立木对光照和养分的竞争[14],且自然恢复还使林分中的物种组成发生变化,改善了土壤的理化性质和林分微环境[15]。MA等[16]和DON等[17]研究表明:森林土壤中的碳循环对林业经营管理措施极为敏感,植被恢复能有效提高退化生态系统的土壤有机碳质量分数。然而,由于不同植被恢复措施下的林分物种种类、地上地下生物量、凋落物量均差异显著,因此其对土壤有机碳库的影响亦显著不同[18],且适度采伐可提升森林的土壤有机碳质量分数[16]。因此,系统研究马尾松松材线虫病林分土壤活性有机碳对采伐强度、植被自然恢复的响应规律,有利于深入了解采伐及植被自然修复对土壤活性有机碳的影响以及与林分间的互作机制。

土壤活性有机碳主要由林分中鲜有机质与腐殖质间的过渡性物质分解而成,林分结构、土壤理化性质以及微环境的变化均会对土壤有机碳的空间变异产生影响,增加它的不稳定性,从而快速表征土壤的碳库变化。王晓荣等[19]发现:抚育间伐1 a后,马尾松林土壤活性有机碳空间异质性增加,总有机碳与微生物生物量碳显著降低。翟凯燕等[20]则发现:中度间伐9 a后的马尾松林土壤总有机碳、颗粒有机碳、易氧化有机碳质量分数提升,而重度间伐林分表现为下降。另有学者研究发现:不同植被恢复措施作用后土壤活性有机碳库出现以下3种情况:显著增加[21]、无显著变化[22]、有所减少[23]。可见,采伐调节林分密度对土壤有机碳的影响以及与林分间的互作机制[24],以及植被恢复后不同演替阶段的森林土壤有机碳变化规律须进一步探索[25]。本研究以中度采伐、重度采伐等2种强度采伐后自然恢复5、15 a的马尾松松材线虫病次生林为研究对象,探讨其土壤有机碳及其活性组分的累积变化特征,旨在深入理解森林经营管理对马尾松次生林土壤有机碳及其活性组分的变异特性,探明采伐后自然恢复对土壤活性有机碳的长期效应,准确评估和调控松材线虫病危害后的马尾松次生林土壤碳库情况,为遭受松材线虫病危害的马尾松林经营管理提供科学依据。

-

研究区位于亚热带地区的浙江省杭州市余杭区与临安区内(29°56′14″~30°34′17″N,118°50′22″~120°20′21″E)。该地属亚热带季风气候,四季分明,海拔为90~243 m,年平均气温为15.4~18.4 ℃,平均相对湿度为70%~81%,年降水量为1 454.0~1 882.0 mm,年无霜期为240.0 d,年日照时数为1 352.0~1 765.0 h。

研究林分为马尾松健康林及遭受松材线虫病危害后的马尾松次生林。林分优势层以马尾松为主,另有木荷Schima superba、杉木Cunninghamia lanceolata、青冈Quercus glauca、朴树Celtis sinensis、樟树Camphora officinarum、漆树Toxicodendron vernicifluum等树种。亚优势层主要有檵木Loropetalum chinense、枫香Liquidambar formosana等。灌木层有赤楠Syzygium buxifolium、山矾Symplocos sumuntia、栀子Gardenia jasminoides、小蜡Ligustrum sinense、柃木Eurya japonica、总序桂Phillyrea latifolia、映山红Rhododendron simsii等。草本层有芒萁Dicranopteris pedata、狗脊Woodwardia japonica、红盖鳞毛蕨Dryopteris erythrosora、阔鳞鳞毛蕨Dryopteris championii、蹄盖蕨Athyrium filix-femina、菝葜Smilax china、欧洲蕨Pteridium aquilinum、青绿薹草Carex breviculmis、蓝眼庭菖蒲Sisyrinchium angustifolium、马银花Rhododendron ovatum、土茯苓Smilax glabra、六月雪Serissa japonica、络石Trachelospermum jasminoides、金樱子Rosa laevigata等。林分土壤类型为红壤,土层深度为45~55 cm。

-

采用空间替代时间法,于2023年春季选取地形、海拔、土壤类型、坡向、坡位等立地条件相近的马尾松林为研究对象。设置5个处理:未遭受松材线虫病危害且未采伐的马尾松林为对照(ck);多年累计采伐株数强度为30%~40%(中度采伐),经自然恢复5 a的马尾松次生林(ML5);多年累计采伐株数强度为60%~80%(重度采伐),经自然恢复5 a的马尾松次生林(HL5);多年累计采伐株数强度为30%~40%(中度采伐),经自然恢复15 a的马尾松次生林(ML15);多年累计采伐株数强度为60%~80%(重度采伐),经自然恢复15 a的马尾松次生林(HL15)。上述林分均为20世纪80年代荒山飞播造林培育而成。被采伐的林木均为疫木。采伐后均未对林地开展补植,自然恢复期间林木均未遭受病虫危害,且无其他经营管理措施。

2023年3—5月,进行林地踏查后在每个林分设置3个625 m2(25 m×25 m)的标准样地,共15块样地,进行样地植物种类调查(表1),并于2023年6月进行土壤物理性质调查及样品采集。具体方法:采用对角线法在每个样地的对角线上设置3个土壤采样点,挖取1 m宽的土壤剖面,按照0~10、10~20、20~40 cm的分层方式进行环刀和土壤样品采样,将土壤样品装入自封袋中混匀后,放于低温保温箱中带回实验室测理化性质。共挖取45个土壤剖面,采集135个环刀及135份土壤样品。环刀用于测定土壤容重、孔隙度、含水率等物理性质。土壤样品剔除石粒、根系、凋落物后过2 mm孔径土筛,将样品分为2份,一份新鲜土样置于4 ℃冰箱中用于测定微生物生物量碳(MBN)、水溶性有机碳(WSOC)、硝态氮(${\mathrm{NO}}_3^- $-N)、铵态氮(NH4 +-N),另一份置于通风处自然风干后用于测定土壤有机碳(SOC)、颗粒有机碳(POC)、易氧化碳(ROC)。

处理 采伐强度 马∶阔数量比 恢复年限/a 主要植物 乔木层 灌草层 ck 未采伐 - - 马尾松、檵木、青冈等 蹄盖蕨、菝葜、欧洲蕨、青绿薹草、蓝眼庭菖蒲等 ML5 中度 7∶3 5 马尾松、木荷、朴树等 芒萁、柃木、山矾、赤楠、马银花等 HL5 重度 2∶8 5 木荷、青冈、马尾松等 赤楠、马银花、山矾、土茯苓、总序桂等 ML15 中度 6∶4 15 马尾松、青冈、樟树、漆树等 栀子、总序桂、映山红、六月雪、络石、金樱子等 HL15 重度 6∶4 15 枫香、漆树、樟树、檵木等 山矾、金樱子、总序桂、菝葜、阔鳞鳞毛蕨等 说明:马指马尾松,阔指阔叶树。−表示无此项。林龄均为40 a。 Table 1. Basic overview of forests under different logging intensities and natural restoration years

-

土壤容重、pH、含水率、孔隙度等参照《土壤农化分析》中的方法测定[26];土壤有机碳质量分数采用K2Cr2O7-H2SO4消煮法测定[27];土壤易氧化碳质量分数采用高锰酸钾氧化法测定[28];土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数采用水浸提法测定[29];土壤微生物生物量碳质量分数采用氯仿熏蒸浸提法测定[30];土壤硝态氮质量分数采用紫外分光光度法测定[31];土壤铵态氮质量分数采用靛酚兰比色法测定[32];土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数采用六偏磷酸钠分散法测定[33]。

-

采用Excel 2016、SPSS 27.0、Origin 2021进行数据统计与分析。正态分布检验后,采用双因素方差分析法分析采伐强度与恢复年限对土壤有机碳及其活性组分的影响,并采用最小显著差异法(LSD)进行显著性检验。采用 Pearson 相关分析法分析有机碳及其组分与土壤理化性质的关系(P<0.05)。

-

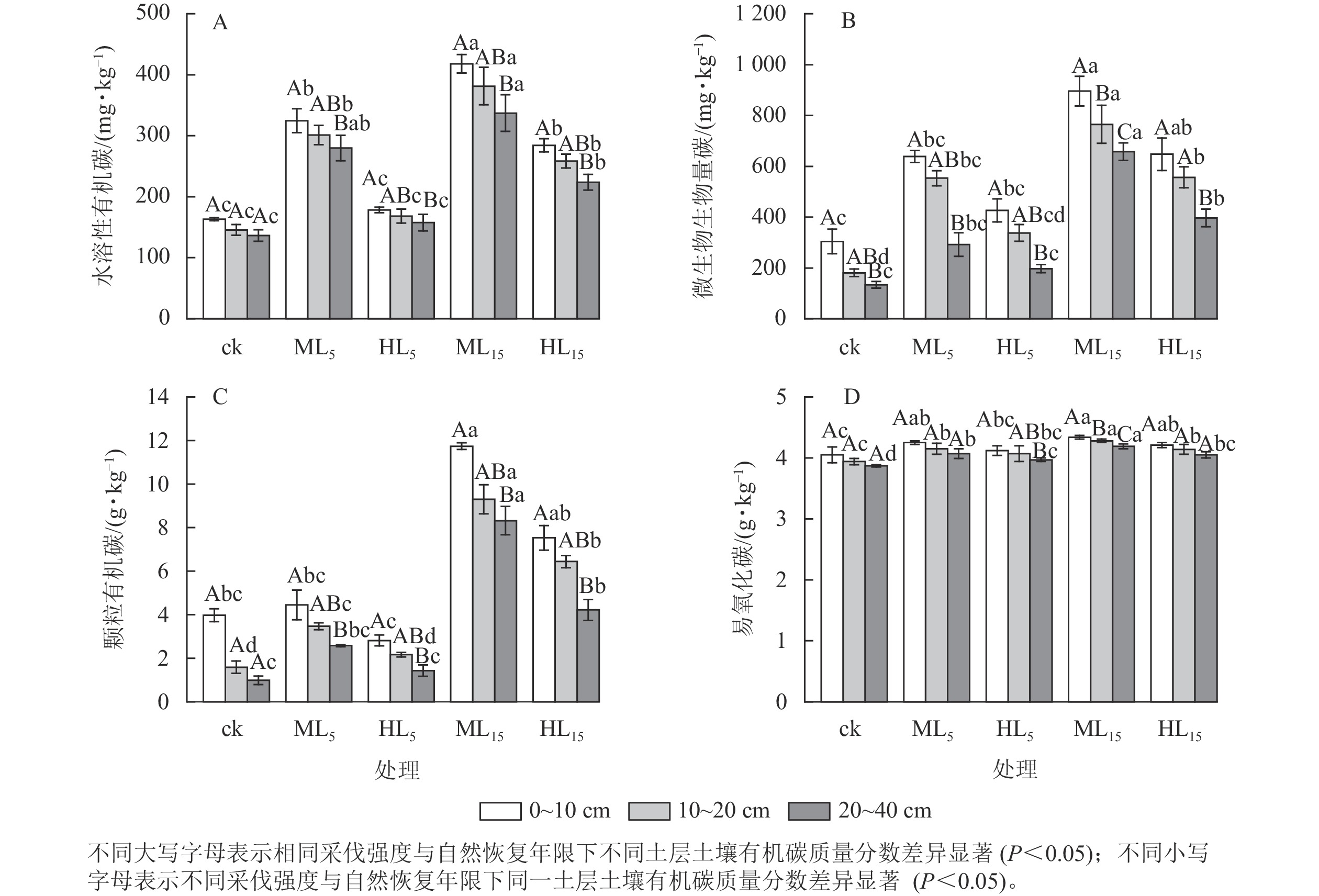

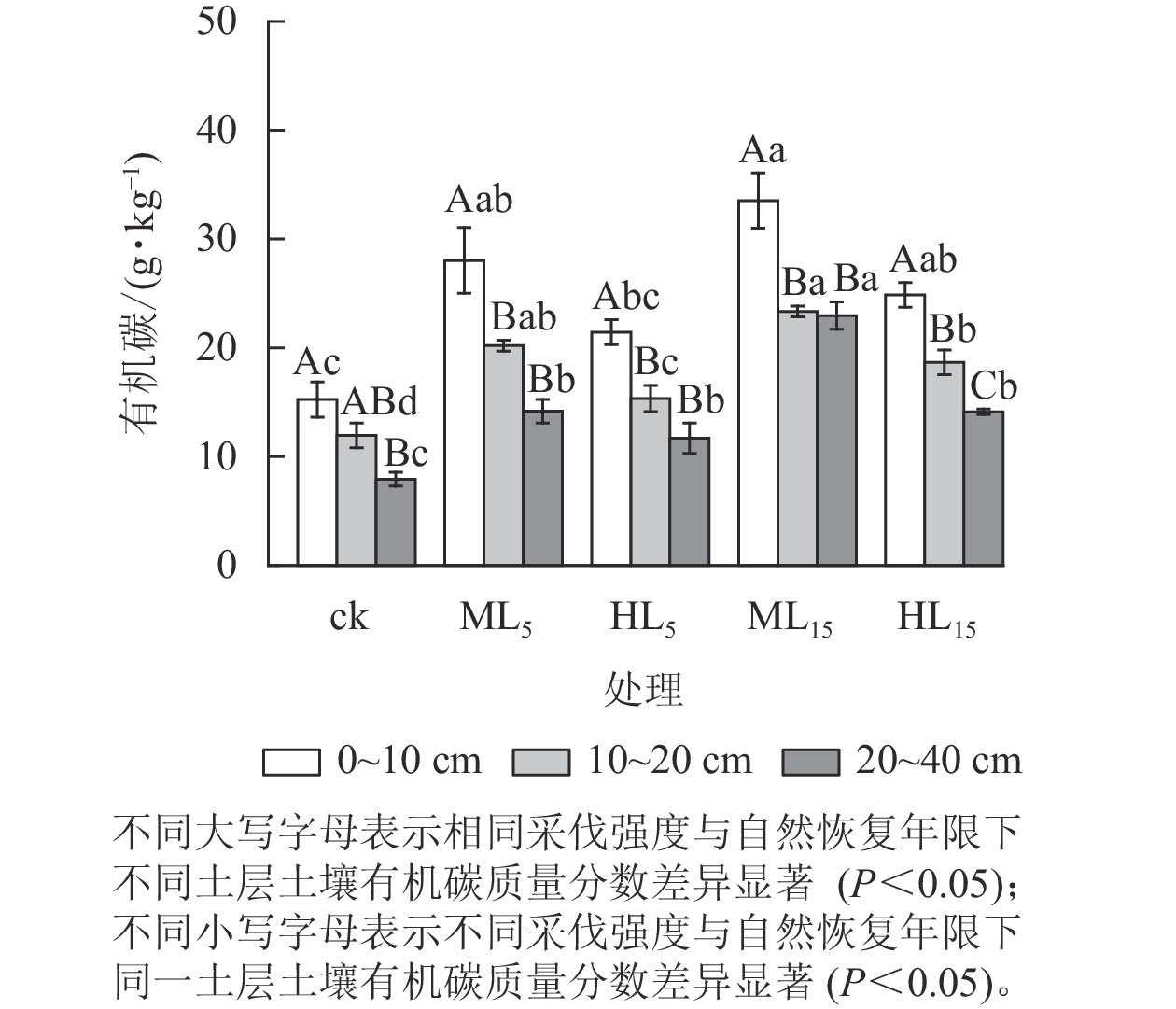

由图1可知:不同采伐强度与恢复年限的马尾松次生林分土壤有机碳质量分数随土层加深而降低,且各处理0~10 cm土层土壤有机碳质量分数均高于20~40 cm土层(P<0.05)。各林分不同土层土壤有机碳质量分数方面,0~10与20~40 cm的2个土层中HL5相差最小,为9.75 g·kg−1,ML5相差最大,为13.86 g·kg−1,各采伐林分均高于ck的7.32 g·kg−1。且各土层ML15显著高于HL5 (P<0.05)。

Figure 1. Changes of soil SOC content in different soil layers under different logging intensities and natural restoration years

不同采伐强度林分的土壤有机碳质量分数方面,与ck相比,采伐后各林分不同土层的土壤有机碳质量分数均有所增加,其中ML5、ML15、HL15显著高于ck (P<0.05),且同一恢复年限下中度采伐的林分(ML5、ML15)均高于重度采伐林分(HL5、HL15)。

采伐后不同恢复年限的林分土壤有机碳质量分数方面,中度采伐与重度采伐林分各土层土壤有机碳质量分数均随着恢复年限的增加而上升。0~10 cm土层的ML15土壤有机碳质量分数最高,为(33.53±7.86) g·kg−1,ML5、ML15 、HL15均显著高于ck (P<0.05)。20~40 cm土层的ML15土壤有机碳质量分数显著高于ML5 (P<0.05),重度采伐的HL15显著大于ck。

-

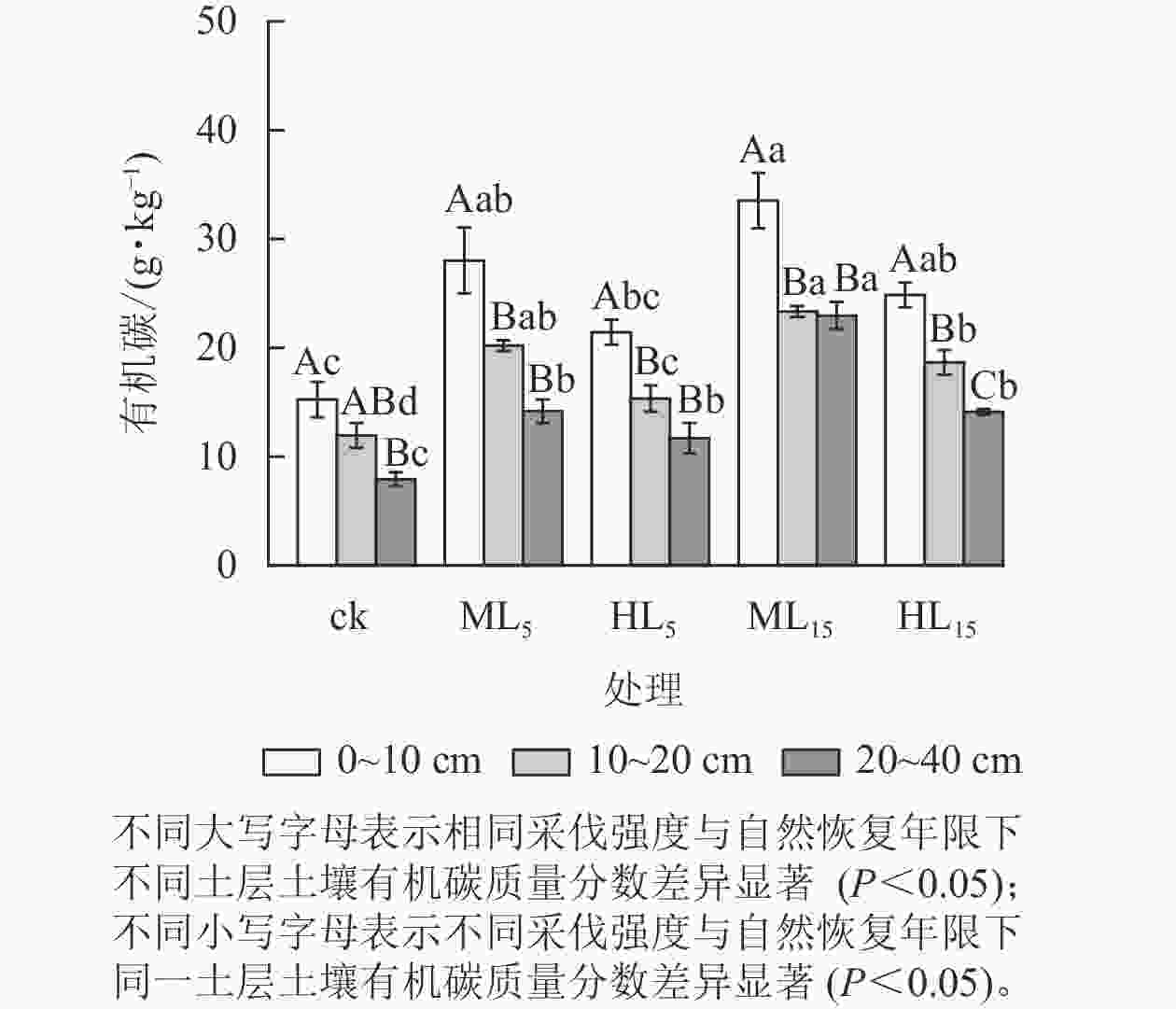

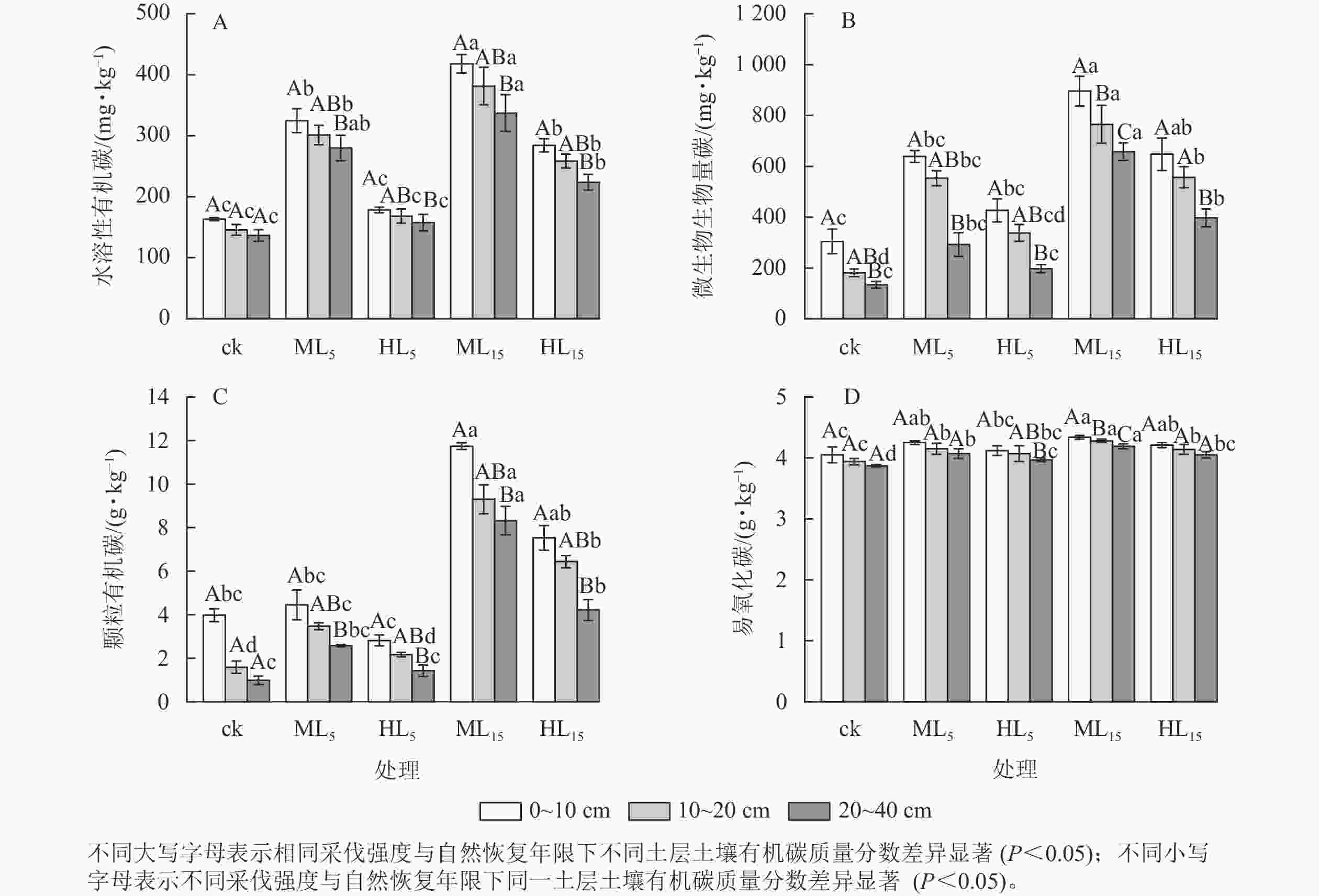

各处理土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数随土层加深而降低(图2A),ML15、HL15林分0~10 cm土层的水溶性有机碳质量分数均显著高于20~40 cm (P<0.05)。同一土层深度下,ML15的水溶性有机碳质量分数最高,显著大于ck、HL5、HL15 (P<0.05),0~10、10~20、20~40 cm各土层的水溶性有机碳质量分数均为ck最低,分别为(163.09±2.33)、(145.57±8.92)、(136.55±9.54) mg·kg−1。不同采伐强度林分的土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数方面,采伐后各林分不同土层均有所增加,0~20 cm土层,ML15、HL15分别显著高于ML5、HL5及ck (P<0.05),且ML5、ML15、HL15均显著高于ck (P <0.05)。采伐后不同恢复年限的林分土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数方面,中度采伐与重度采伐林分各土层均随着恢复年限的增加而上升,最高为0~10 cm土层下ML15,为(417.96±26.13) mg·kg−1,是ck的2.56倍。

Figure 2. Changes of soil ROC, POC, MBC, and WSOC content in different soil layers under different logging intensities and natural restoration years

各处理土壤微生物生物量碳随土层加深而降低(图2B),且各林分0~10 cm土层的微生物生物量碳质量分数均显著高于20~40 cm (P<0.05),ML15的各土层微生物生物量碳质量分数差异显著(P<0.05)。各处理不同土层的微生物生物量碳质量分数方面,0~10与20~40 cm 土层中 HL5相差最小,为229.13 mg·kg−1,ML5相差最大,为298.99 mg·kg−1,各采伐林分均高于ck的176.18 mg·kg−1,且ML15显著高于HL5 (P<0.05)。不同采伐强度林分的土壤微生物生物量碳质量分数方面,采伐后各林分不同土层均高于ck,同一恢复年限下各土层的中度采伐林分(ML5、ML15)均高于重度采伐林分(HL5、HL15)。采伐后不同恢复年限的林分土壤微生物生物量碳质量分数方面,恢复年限为15 a的2种不同采伐林分(ML15、HL15)均分别显著高于ML5、HL5 (P<0.05),且中度采伐与重度采伐林分各土层微生物生物量碳质量分数均随着恢复年限的增加而上升,最高为0~10 cm 土层下ML15,为(895.87±158.71) mg·kg−1,其中ML15、HL15均显著高于ck (P<0.05)。

各处理土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数随土层加深而降低(图2C),其中ML5、HL5、ML15、HL15的0~10 cm土层的颗粒有机碳质量分数显著高于20~40 cm (P<0.05)。各林分不同土层颗粒有机碳质量分数方面,ML15均为最高,ck均为最低,ML15显著高于ck、ML5、HL5 (P<0.05),为0~10、10~20、20~40 cm相同土层下ck的3.0、7.4、11.8倍。不同采伐强度林分的土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数方面,采伐后各林分不同土层均有所增加,其中ML15、HL15显著高于ck (P<0.05),且同一恢复年限下重度采伐林分(HL5、HL15)均低于中度采伐林分(ML5、ML15),ML15与HL15差异显著(P<0.05)。采伐后不同恢复年限的林分土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数方面,中度采伐与重度采伐林分各土层颗粒有机碳质量分数均随着恢复年限的增加而上升,最高为0~10 cm 土层下ML15,为(11.74±0.26) g·kg−1,15 a恢复期的林分(ML15、HL15)分别显著高于5 a恢复期的林分(ML5、HL5,P<0.05),且ML15、HL15的颗粒有机碳质量分数至少为0~10、10~20、20~40 cm相同土层下ML5、HL5林分的2.60倍以上。

如图2D所示:各林分土壤易氧化碳质量分数随土层加深而降低,其中HL5、ML15的0~10 cm土层易氧化碳质量分数显著高于20~40 cm (P<0.05), ML15的各土层间差异显著(P<0.05)。各林分不同土层的易氧化碳质量分数方面,ML15的0~10 cm最高,为(4.34±0.03) g·kg−1,且10~20、20~40 cm土层ML15均显著高于其他林分(P<0.05)。不同采伐强度林分的土壤易氧化碳质量分数方面,中度采伐与重度采伐林分各土层均随着恢复年限的增加而上升,其中ML5、ML15、HL15显著高于ck (P<0.05),且同一恢复年限下重度采伐林分(HL5、HL15)均低于中度采伐的林分(ML5、ML15)。采伐后不同恢复年限的林分土壤易氧化碳质量分数方面,各采伐强度的林分土壤易氧化碳质量分数随恢复年限延长而显著增加(P<0.05)。

-

双因素方差检验结果(表2)表明:采伐强度及植被自然恢复年限是土壤有机碳及其活性组分质量分数的显著影响因素(P<0.05),其中,采伐强度对土壤活性有机碳组分质量分数的影响达极显著(P<0.001),植被自然恢复年限则对土壤微生物生物量、水溶性有机碳、易氧化碳、颗粒有机碳有极显著影响(P<0.001)。而采伐强度与植被自然恢复年限的交互作用仅对土壤颗粒有机碳有显著影响(P<0.05)。

影响因子 采伐强度 恢复年限 采伐强度×恢复年限 F P F P F P 有机碳 11.440 <0.050 6.247 <0.050 0.647 0.426 微生物生物量碳 14.838 <0.001 29.273 <0.001 1.100 0.301 水溶性有机碳 133.725 <0.001 54.664 <0.001 0.223 0.640 易氧化碳 15.781 <0.001 9.498 <0.001 0.346 0.560 颗粒有机碳 18.922 <0.001 76.350 <0.001 4.111 <0.05 Table 2. Two-way ANOVA of soil organic carbon and its active components under logging and natural restoration

-

如表3所示:各林分土壤pH为4.23~4.47,容重为0.96~1.40 g·cm−3,土壤含水率为12.05%~20.00%,土壤孔隙度41.05~52.40 mg·kg−1。硝态氮与铵态氮质量分数呈现为随着土层加深而降低的趋势,且随植被恢复年限的延长而增加,最高均为0~10 cm土层ML15林分。采伐强度对土壤pH、容重、硝态氮有极显著影响(P<0.01),对土壤含水量、铵态氮有显著性影响(P<0.05);恢复年限仅对硝态氮有极显著影响(P<0.01),对土壤孔隙度、铵态氮有显著性影响(P<0.05);采伐强度及恢复年限的交互作用对pH和土壤容重有显著性影响(P<0.05)。

处理 土层/cm pH 容重/(g·cm−3) 含水量/% 孔隙度/% 硝态氮/(mg·kg−1) 铵态氮/(mg·kg−1) ck 0~10 4.31±0.04 Aa 1.33±0.20 Aa 12.05±5.84 Aa 42.92±1.36 Ab 2.21±0.21 Ac 2.89±0.29 Ac 10~20 4.30±0.06 Ab 1.40±0.18 Aa 14.63±5.27 Aa 42.53±1.25 Ab 1.52±0.23 Bc 2.33±0.78 Ad 20~40 4.27±0.04 Aa 1.35±0.09 Aa 17.84±4.80 Aa 41.05±2.62 Ab 1.17±0.06 Bb 2.08±0.68 Aa ML5 0~10 4.32±0.06 Aa 0.96±0.10 Bc 20.00±1.53 Aa 52.40±2.72 Aa 3.84±0.54 Ab 5.52±1.41 Abc 10~20 4.33±0.04 Ab 1.05±0.08 Bc 15.33±0.67 Ba 51.16±2.46 Aa 2.79±0.38 Bb 4.58±0.66 Abc 20~40 4.24±0.03 Aa 1.15±0.05 Ab 16.00±0.58 Ba 49.28±0.19 Aa 2.05±0.40 Bab 4.02±0.47 Aa HL5 0~10 4.24±0.01 Aa 1.02±0.12 Ac 12.33±0.33 Aa 45.43±2.93 Aab 2.54±0.31 Ac 4.33±0.50 Abc 10~20 4.34±0.03 Ab 1.10±0.12 Ac 15.67±1.45 Aa 48.65±1.36 Aab 2.14±0.48 ABbc 3.39±1.17 Acd 20~40 4.30±0.09 Aab 1.16±0.08 Aab 10.67±2.60 Aa 43.95±2.49 Aab 1.57±0.25 Bb 2.46±0.99 Aa ML15 0~10 4.32±0.06 Aa 1.29±0.12 Aab 19.03±1.74 Aa 49.21±2.30 Aab 6.68±0.46 Aa 13.71±2.61 Aa 10~20 4.31±0.09 Ab 1.29±0.13 Aab 18.01±1.51 Aa 47.48±1.15 Aab 4.87±0.41 ABa 6.33±0.93 Ba 20~40 4.23±0.07 Aa 1.36±0.04 Aa 18.06±1.32 Aa 48.25±2.20 Aab 3.72±0.93 Ba 4.02±1.88 Ba HL15 0~10 4.31±0.17 Aa 1.07±0.06 Abc 19.11±2.21 Aa 49.92±0.75 Aab 4.53±0.47 Ab 6.27±0.66 Ab 10~20 4.23±0.03 Aa 1.25±0.04 Aab 18.38±0.79 Aa 46.30±2.44 Aab 3.01±0.57 ABb 5.46±0.68 ABab 20~40 4.47±0.09 Aa 1.20±0.19 Aab 17.83±0.48 Aa 45.35±2.98 Aab 2.10±0.50 Bab 3.77±0.71 Ba L - ** ** * - ** * Y - - - - * ** * L×Y - * * - - - - 说明:不同大写字母表示相同采伐强度与自然恢复年限下不同土层土壤理化性质差异显著(P<0.05);不同小写字母表示不同采伐强度与自然恢复年限下同一土层土壤理化性质差异显著 (P<0.05)。L表示采伐强度,Y表示恢复年限。*表示0.05水平下差异显著,**表示0.01水平下差异极显著,-表示无显著影响。 Table 3. Soil physical and chemical factors and two-way ANOVA analysis in forest stands under different logging intensities and natural restoration years

-

相关分析可知(图3):土壤有机碳及其活性组分之间均呈显著正相关关系(P<0.05),其中,土壤易氧化碳与与土壤微生物生物量碳相关系数最高,达0.87。土壤容重与土壤有机碳显著负相关(P<0.05),土壤含水率与土壤微生物生物量碳、土壤水溶性碳、土壤颗粒有机碳间表现出显著正相关(P<0.05);土壤硝态氮、土壤铵态氮与土壤有机碳及其活性组分间亦为显著正相关(P<0.05)。

-

间伐等森林采伐管理措施对固存土壤有机碳影响较大[16]。本研究发现:适度采伐提高了土壤有机碳及其活性组分质量分数,这一结果与之前的研究结果类似。王昌亮等[34]研究表明:40%采伐强度的落叶松Larix gmelinii人工林0~60 cm土层中的土壤有机碳、土壤易氧化有机碳显著高于对照;MA等[16]研究表明:适度采伐(30%采伐强度)的华北落叶松Larix principis-rupprechtii林土壤有机碳和土壤易氧化有机碳明显高于重度采伐及低强度采伐林分。究其原因为中度采伐提高了林分的地上凋落物和地下植物细根量,而重度采伐下的林分一段时间内碳源不足,林分微环境的碳循环能力减弱,致使其土壤中的有机碳质量分数降低。同时,土壤易氧化有机碳、土壤颗粒有机碳、土壤微生物生物量碳、土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数从高到低均表现为中度采伐、重度采伐、ck,其原因可能在于中度采伐的林分植被覆盖更为完整,所提供的有机物质如凋落物等在土壤中分解后形成易氧化碳、颗粒有机碳等[19],植被还可以通过根系分泌物和凋落物的形式向土壤中输入水溶性有机碳。从土壤微生物活性来说,中度采伐对于土壤扰动小于重度采伐,同时增加林地光照,改善通气状况,有利于植物细根的生长并促进土壤微生物的活动,加速地上与地下凋落物的分解,增加微生物生物量碳及颗粒有机碳来源[20];中度采伐对林分的人为干扰小于重度采伐,对森林结构的完整性破坏较小,有利于土壤生态系统恢复和有机物质的积累,从而提高土壤碳的质量分数[34]。当表层土壤有机碳的黏结点达到饱和时,易氧化碳将其解析并以水溶性有机碳的形式向土壤深层移动。水溶性有机碳可以提高土壤中稳定性有机碳的分解,土壤活性有机碳质量分数随之升高[35]。

-

自然恢复年限对土壤有机碳及其活性组分变化产生显著影响,它们的质量分数均随恢复年限增长而增加。相同采伐强度下的马尾松次生林土壤有机碳、土壤易氧化碳、土壤微生物生物量碳、土壤颗粒有机碳、土壤水溶性有机碳质量分数均与其植被自然恢复年限成正比。活性有机碳组分是土壤中植物和微生物具有较高可利用性的化学活性组分,可作为土壤碳库稳定的指示因子,表征土壤碳库稳定性[35],如混交林土壤活性有机碳与土壤有机碳的占比低于纯林,土壤碳库稳定性更强[36],这与本研究结果一致。土壤颗粒有机碳主要是与砂砾结合的动植物半残体分解物组成,是有机碳中的非保护性部分[37]。本研究中土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数表现为0~10 cm土层大于10~40 cm土层,这与尚瑶等[38]的研究结果相符。其原因可能是自然恢复过程中会增加动植物残体、凋落物等,这些物质的增加会促使易氧化碳和颗粒有机碳的形成[27],从而提高其质量分数。而土壤水溶性有机碳随恢复年限增加呈显著增加的原因在于土壤水溶性有机碳主要来源于凋落物、植物残体腐殖质等,恢复年限越长的林分中有机质越高[39]。植被的改善有利于土壤吸收更多的根系分泌物和凋落物[21],促进微生物的发展和生长,提高微生物生物量碳的质量分数。同时,微生物的活动也有助于土壤有机质的分解和转化[23],影响其他有机碳组分的质量分数。随着有机质的积累和微生物的作用,土壤结构得到改善,土壤中养分的有效循环提高植物生产力,增加土壤有机碳的输入,有利于土壤有机碳的累积。

-

马尾松次生林经适度采伐后,出现大量林窗,增加了灌草生长空间,凋落物、细根生物量随之增加,土壤有机碳碳源得到补充;随着植被恢复,植物种类增加,群落组成结构趋于复杂,提高了土壤微生物底物的可利用性,促进土壤微生物生长和活性,有利于土壤碳的累积。马尾松次生林土壤有机碳质量分数随土层加深而降低,符合凋落物、根系等碳源集中在表层土的特征[39]。土壤颗粒有机碳、土壤微生物生物量碳等是土壤活性有机碳的重要组分[40],因而各活性组分亦表现为随土层深度增加其有效性降低的规律[9, 41]。本研究中土壤颗粒有机碳、土壤水溶性有机碳、土壤易氧化碳、土壤微生物生物量碳均与土壤有机碳存在极显著的正相关关系。这与王斐等[42]、朱浩宇等[43]的研究结果相符合,显示土壤有机碳是影响活性有机碳主要的决定性因素。活性有机碳组分之间也呈现极显著正相关关系,表明其关系密切,作为活性碳库的成分,共同影响土壤有机碳周转。土壤硝态氮、土壤铵态氮与有机碳及其组分均存在极显著正相关关系,表明氮素有效性也是影响有机碳及其组分的关键。本研究中,采伐后林分土壤硝态氮、铵态氮质量分数均高于未采伐林分,并随着恢复时限的增长而增加。氮素的增加会刺激植物生长,从而增加根系分泌物和凋落物的产生[3],同时可能会促进微生物的生长和活性,加速其对有机质的分解,影响有机碳的稳定性和质量分数。本研究中,采伐后的马尾松次生林土壤含水率高于未采伐林分。土壤含水率的提高通常有利于土壤中有机物质的保持,减少矿化,这促使土壤有机碳和易氧化碳的积累[44]。良好的水分条件亦有益于微生物活动环境,促进微生物生物量碳的增加[45]。土壤容重的大小反映土壤结构、质地和腐殖质等的变化,从而影响有机碳的变化。本研究发现:土壤容重与土壤有机碳呈现显著负相关关系。这与袁星明等[46]的研究结果相符合。相比ck,马尾松次生林采伐后的土壤容重有所降低,意味着土壤质地变得更加疏松,有助于提高土壤的通气性和水分保持能力,为微生物活动提供更好的环境,促使其更有效地分解有机质,从而增加土壤有机碳、土壤易氧化碳、土壤颗粒有机碳质量分数[9]。采伐后的林分土壤孔隙度高于ck,有利于改善土壤结构,增加空气和水的渗透性,为植物根系生长和微生物活动提供良好的环境,减少有机物质的干燥和氧化,有助于维护有土壤有机碳的稳定性,增加土壤有机碳及其活性组分的质量分数[9]。

-

采伐对马尾松林分土壤有机碳及其活性组分质量分数具有显著的促进作用,形成的马尾松次生林微环境,加快了土壤活性有机碳组分的转化,尤其是0~10 cm土层的有机碳及其活性组分质量分数对采伐的响应更为敏感。30%~40%中度采伐的改善作用强于60%~80%的重度采伐。

采伐后马尾松次生林土壤有机碳及其活性组分质量分数与植被自然恢复年限呈显著正相关。15 a自然恢复年限的土壤有机碳库显著高于5 a的自然恢复年限及未采伐的马尾松林分,且各活性有机碳组分对自然恢复年限的响应趋势相同。

土壤中的有机碳及其活性组分间具有协同提升的作用。土壤不同活性有机碳组分对马尾松次生林采伐强度与自然恢复年限的响应是通过改变林下植物种类、改善林木生长空间和光温水热等复杂的生物与非生物因素驱动的。因此,在森林经营条件许可的情况下,可以针对马尾松纯林进行适当强度的采伐,选择适地树种人工促进更新,加快针叶纯林演替成混交林,促进森林土壤碳循环,增加土壤有机碳库。

Effects of natural vegetation restoration after logging on soil organic carbon and its active components in Pinus massoniana secondary forests

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20240264

- Received Date: 2024-03-26

- Accepted Date: 2024-07-15

- Rev Recd Date: 2024-07-09

- Available Online: 2024-08-29

- Publish Date: 2024-11-20

-

Key words:

- soil organic carbon /

- Pinus massoniana secondary forest /

- logging /

- natural restoration of vegetation /

- pine wilt disease

Abstract:

| Citation: | HU Ao, ZHAO Yihui, WU Jilai, et al. Effects of natural vegetation restoration after logging on soil organic carbon and its active components in Pinus massoniana secondary forests[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2024, 41(6): 1189-1200. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20240264 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: