-

砷(As)作为剧毒且致癌的类金属元素,可通过食物链富集,对环境、食品安全和人体健康产生负面影响[1−3]。根据2014年《全国土壤污染状况调查公报》,As已成为中国农业土壤中普遍存在的污染物。化肥、农药的不合理使用以及矿山开采和金属冶炼活动,导致含As固体废物和废水排放增加,加剧了As污染,并恶化了土壤和水体的As污染状况[4]。鉴于其毒性,开发有效的As污染治理技术成为全球关注焦点。As在环境中主要以砷酸盐和亚砷酸盐形式存在[5],相较于传统的沉淀、膜过滤和离子交换等治理方法,吸附技术因其高效、低成本和操作简便,被认为是一种极具潜力的As污染治理手段,值得深入研究和应用[6]。

生物质炭是一种通过在缺氧条件下热解废弃生物质所制备的富含碳的固态材料,具有较大的比表面积和丰富的官能团,对重金属(类金属)表现出高效的吸附能力[7],因而在重金属污染治理领域展现出巨大的应用潜力。作为南方典型园林植物,细叶榕Ficus microcarpa修剪产生的枝条常因处理不当被焚烧或填埋,造成资源浪费和环境污染。为了实现细叶榕枝条的高值化利用,已有学者将其制备成生物质炭用于重金属吸附处理,并取得了较好的效果[8]。然而,As主要以含氧阴离子形式存在,而生物质炭表面通常带负电荷,这种电荷特性限制了其对As的吸附效果[9]。因此,需通过功能化改性提升生物质炭对As的吸附和修复能力。

生物质炭改性的目的是拓展其应用范围并提升性能[10]。含铁材料改性的生物质炭不仅能有效吸附地下水和土壤中的As[11],还可促使三价砷[As(Ⅲ)]氧化为更易吸附及更稳定的五价砷[As(Ⅴ)][12]。有研究表明:pH小于6.5时,生物质炭负载四氧化三铁(Fe3O4)对As的去除效率比原始生物质炭提高近40倍[13]。戴志楠等[14]使用氯化铁(FeCl3)对生物质炭进行改性,降低了原始生物质炭的pH,显著降低了土壤中有效态As及水稻Oryza sativa植株中As的含量。王慧戈等[15]研究发现:pH为4.0~8.0时,硫铁改性生物质炭对砷铅复合污染土壤中As的稳定化效率大于75%,远远优于原始生物质炭。现有研究显示:铁基改性生物质炭对As吸附性能卓越,FeCl3和硫酸铁[Fe2(SO4)3]已被广泛用于其制备,并在重金属治理中成效显著。聚合硫酸铁(polymerized ferric sulfate, PFS)作为高效无机高分子混凝剂,在水处理领域表现优异[16],但用于制备铁基改性生物质炭的研究较少。因此,本研究以细叶榕枝条为原料,分别用FeCl3、Fe2(SO4)3和PFS制备原始及铁基改性生物质炭,通过表征和静态吸附实验剖析As吸附影响因素与机理,筛选最佳改性材料,旨在为铁基改性细叶榕生物质炭治理As污染提供理论依据,推动环境修复技术发展。

-

细叶榕修剪枝条收集于广东省佛山市某公园,经切碎处理后85 ℃烘干备用。硝酸(HNO3)、氢氧化钠(NaOH)、FeCl3、Fe2(SO4)3、PFS、亚砷酸钠(NaAsO2)、硝酸钠(NaNO3)均为分析纯,购自阿拉丁试剂(上海)有限公司,实验用水均为超纯水。

-

将烘干后的细叶榕枝条碎片放入小型炭化设备(ECO-8-10),以20 ℃·min−1的速率升温至500 ℃后,在限氧条件下热解2 h,制得细叶榕生物质炭(FMB),生物质炭经研磨后过2 mm不锈钢筛备用。改性生物质炭的制备:采用浸渍热解法对细叶榕修剪枝条进行前处理,即将碎屑按照炭铁质量比20∶1分别浸泡于FeCl3、Fe2(SO4)3、PFS溶液中,充分搅拌后在105 ℃下烘干至恒量。将处理后的生物质置于同一炭化设备中,同样以20 ℃·min−1的速率升温至500 ℃,在限氧条件下热解2 h,制得氯化铁改性生物质炭(FC-FMB)、硫酸铁改性生物质炭(FS-FMB)、聚合硫酸铁改性生物质炭(PFS-FMB),经研磨后过2 mm不锈钢筛备用。

-

测定生物质炭的pH、灰分及碳(C)和氮(N)等元素,其中元素以质量分数的形式表示。生物质炭比表面积采用比表面积分析仪(TristarⅡ3020)测定。通过傅里叶红外光谱仪(FTIR,NICOLET iS20)分析生物质炭表面官能团,获得生物质炭表面官能团种类。X射线衍射分析(XRD)利用X射线衍射仪(D8advance)进行。采用X射线光电子能谱仪(XPS,Thermo ESCALAB 250Ⅺ)分析生物质炭表面元素组成及化学状态,其中表征分析的吸附后材料是在吸附实验中确定的最佳吸附条件下重新制备的生物质炭。生物质炭的表面形貌特征通过扫描电子显微镜(SEM,Sigma 300)分析。生物质炭中总铁质量分数使用硝酸-氢氟酸-高氯酸三酸消解法进行消解,并通过电感耦合等离子体质谱法测定。

-

使用0.01 mol·L−1的NaNO3溶液作为背景电解质以保持储备液浓度的稳定。As(Ⅲ)具有较高的毒性和较强的迁移性,通常比As(Ⅴ)更具危害性,因此选用亚砷酸盐作为As(Ⅲ)的来源,以探究改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附性能。生物质炭与溶液的质量体积比采用最佳比例:2.5 g·L−1[17]。

-

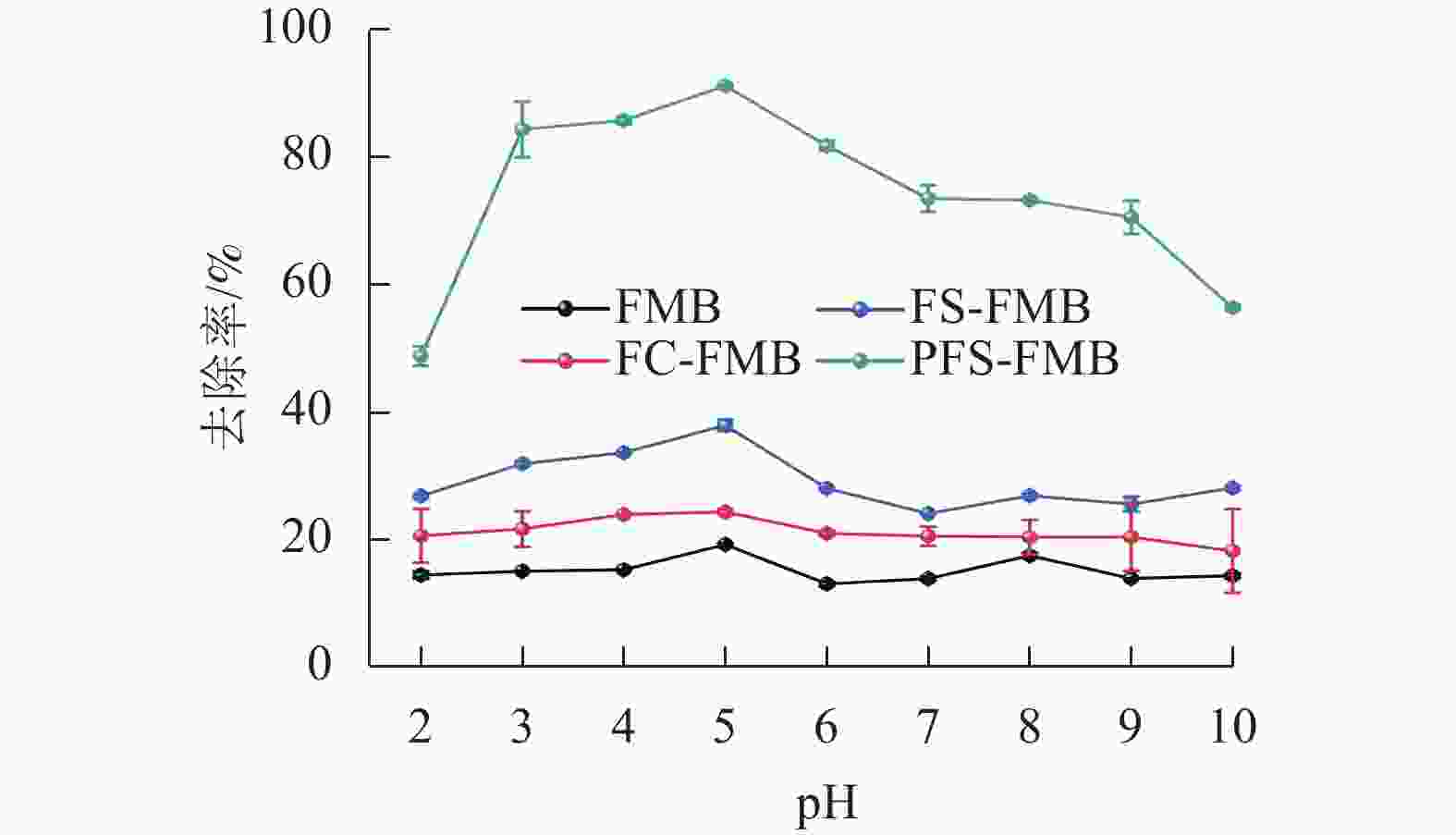

分别称取0.05 g FMB、FC-FMB、FS-FMB、PFS-FMB置于50 mL离心管,加入20 mL质量浓度为40 mg·L−1(以As计),初始pH分别为2、3、4、5、6、7、8、9、10的NaAsO2溶液(采用0.1 mol·L−1 NaOH或0.1 mol·L−1 HNO3调节溶液pH),置于恒温振荡箱中,在恒温25 ℃及 220 r·min−1条件下振荡24 h。然后在4 000 r·min−1条件下离心10 min,取上清液过0.45 μm滤膜(PES)后,利用电感耦合等离子体发射光谱仪(ICP-OES,PerkinElmer 8300)测定As质量浓度。

-

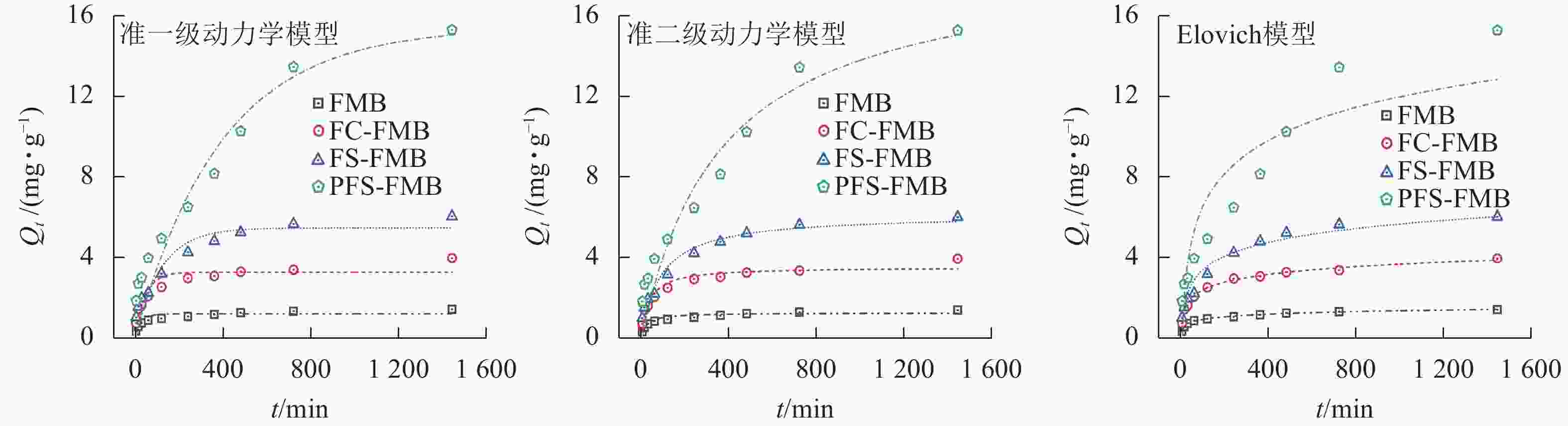

分别称取0.05 g FMB、FC-FMB、FS-FMB、PFS-FMB置于50 mL离心管中,加入20 mL质量浓度为60 mg·L−1的NaAsO2溶液(pH为5)。将离心管放入恒温振荡箱中,在25 ℃、220 r·min−1 条件下振荡5、15、30、60、120、240、360、480、720、1 440 min。振荡后取出,4 000 r·min−1条件下离心10 min,上清液过0.45 μm滤膜,稀释后利用ICP-OES测定As质量浓度。

计算不同时刻生物质炭As吸附量,通过准一级动力学模型、准二级动力学模型[18]以及 Elovich 模型[19]进行动力学拟合,研究生物质炭及改性生物质炭材料对As的吸附动力学。

式(1)为准一级动力学模型,式(2)为准二级动力学模型。Qt为t时刻生物质炭的吸附量(mg·g−1);Qe为生物质炭的平衡吸附量(mg·g−1);k1为准一级动力学方程的吸附速率常数(min−1);k2为准二级动力学方程的吸附速率常数(g·mg−1·min−1)。

Elovich模型被广泛应用于描述水溶液污染物的吸附过程,该模型的假设是吸附剂表面具有高度的不均匀性。其方程式为:$ {Q}_{t}=\alpha +\beta \mathit{{\mathrm{ln}}}t $。其中,$ \alpha $为初始Elovich吸附速率(mg·mg−1·min−1);$ \beta $为与化学吸收活化能和表面覆盖率有关的Elovich解吸常数(g·mg−1)。

-

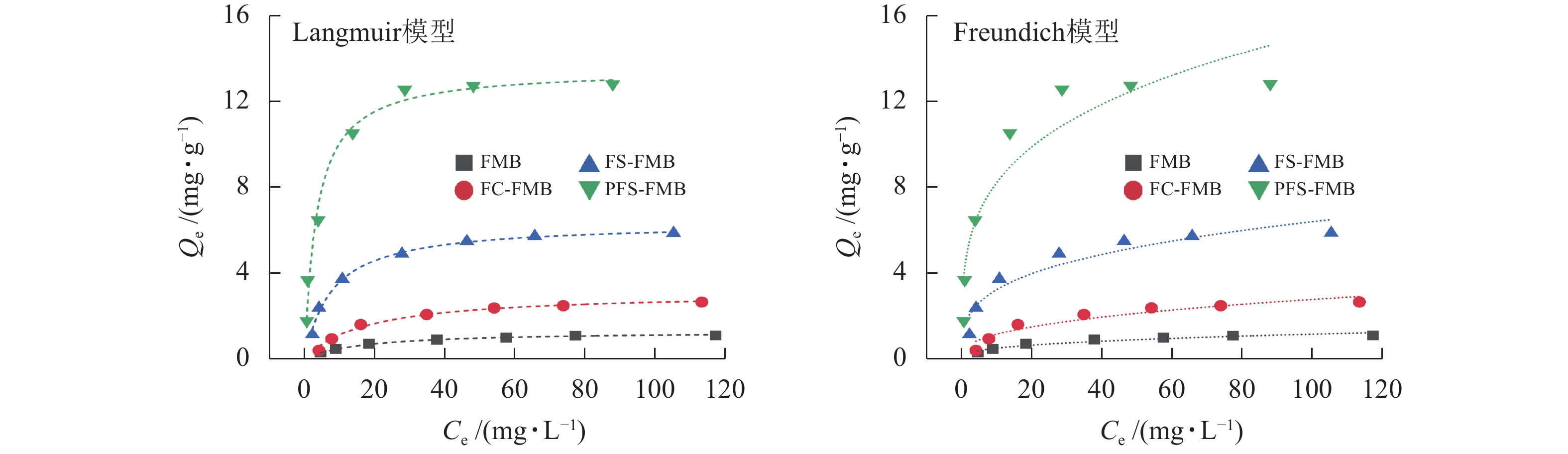

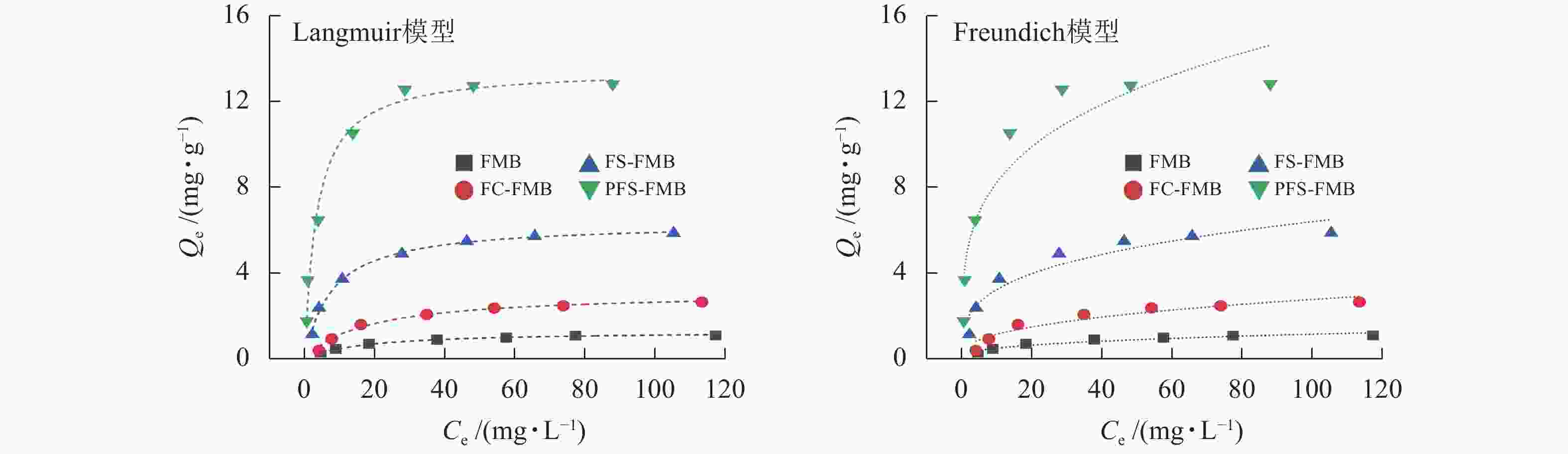

称取0.05 g生物质炭样品于50 mL离心管中,分别加入20 mL质量浓度为5、10、20、40、60、80、120 mg·L−1的NaAsO2溶液(pH为5),在25 ℃,220 r·min−1条件下振荡24 h后取出,4 000 r·min−1条件下离心10 min,上清液过0.45 μm滤膜,ICP-OES测定As质量浓度,并采用Langmuir和Freundlich模型进行拟合。

Langmuir模型反映了单分子层吸附剂单位吸附量与溶液中离子浓度的关系[20],方程式为:$ {Q}_{\mathrm{e}}=\dfrac{{Q}_{\mathrm{m}}{K}_{\mathrm{L}}{C}_{\mathrm{e}}}{1+{K}_{\mathrm{L}}{C}_{\mathrm{e}}} $。其中:Qe为生物质炭的平衡吸附量(mg·g−1);Qm为As的最大吸附量(mg·g−1);KL为吸附常数(L·mg−1);Ce为吸附平衡时的溶液中As质量浓度(mg·L−1)。

Freundlich模型是基于多相吸附表面或表面支撑的活性位点具有不同表面能的猜想建立的经验表达式[21],其方程式为:$ {Q}_{\mathrm{e}}={K}_{\mathrm{F}}{C}_{{\mathrm{e}}}^{N} $。其中,Qe为生物质炭的平衡吸附量(mg·g−1);KF为吸附系数(mg1−N·LN·g−1);Ce为吸附平衡时的溶液中As质量浓度(mg·L−1);N为吸附强度的常数。

-

每处理设置3个重复,最终结果以平均值表示。运用Excel、Origin Pro 2021、SPSS 19.0、Jade 6等软件对数据进行处理与分析。

-

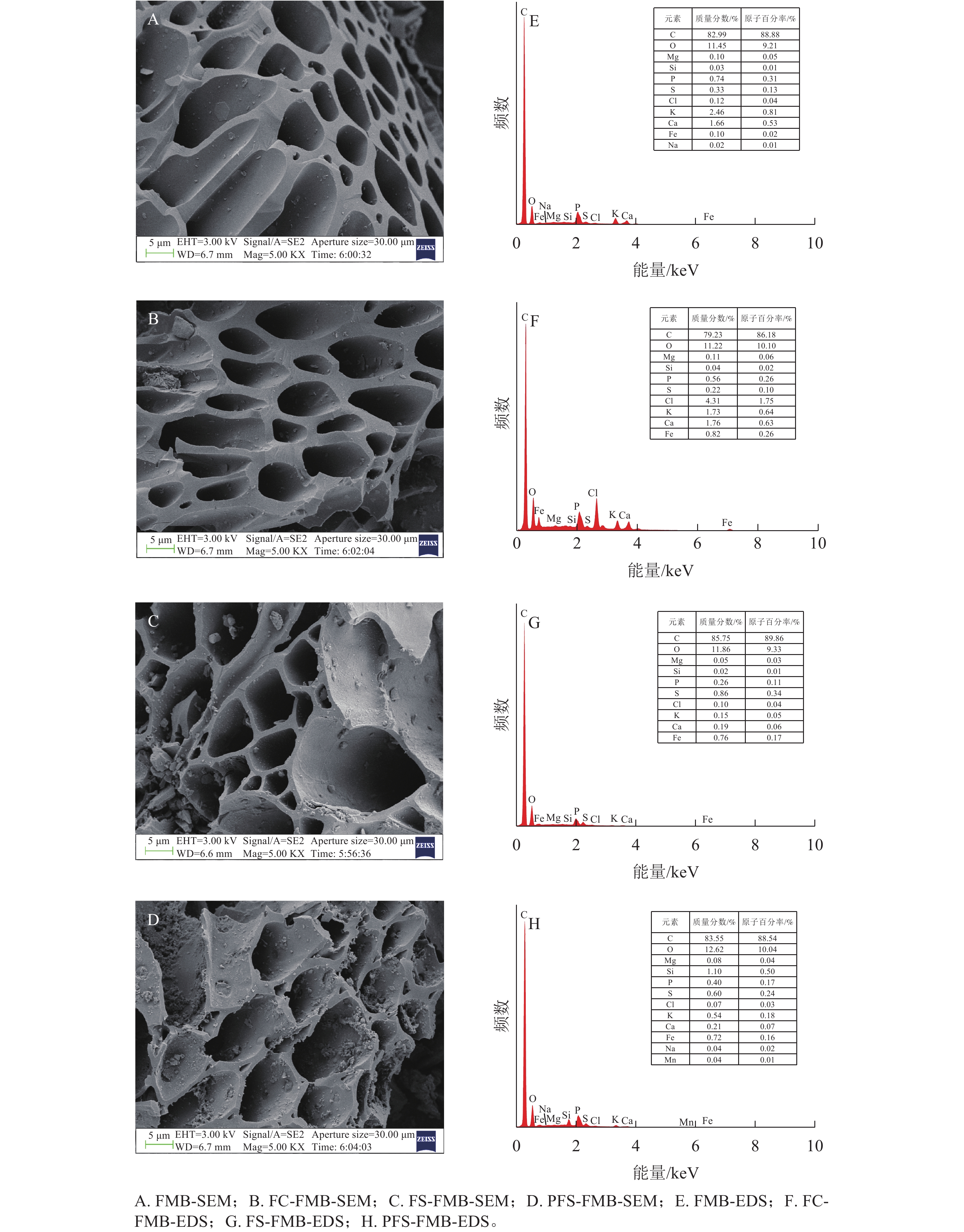

如图1A~D所示:生物质炭均呈现出规则排列的管状微观结构,这一特性可归因于低温热解过程中部分碳骨架得以保留,从而维持了原始生物质中的导管结构[8]。经过铁基改性后的生物质炭表面粗糙度增加,且在其微孔结构和管状通道中观察到大量颗粒状物质。这是由于在加热条件下,酸性环境对生物质炭表面产生了腐蚀作用,使其表面变得粗糙,而这些颗粒状物质主要由铁(Fe)构成的细小颗粒组成。EDS半定量分析结果(图1E~H)表明:FC-FMB表面的Fe和氯(Cl)质量分数明显增加,而FS-FMB和PFS-FMB表面的Fe和硫(S)质量分数也得到增加。上述结果表明,FeCl3、Fe2(SO4)3和PFS 3种改性材料均成功负载于生物质炭表面。

生物质炭的理化性质表明(表1):铁基改性极大提升了生物质炭的比表面积。其中,以PFS-FMB比表面积提升最为明显,相比FMB增加了422.38%。已有研究表明:在酸性环境中,生物质炭的孔隙结构和表面特性会发生极大改变[22]。低温制备的生物质炭保留了生物质的碳骨架,但酸处理会侵蚀其表面微粒。在加热过程中,酸与炭的相互作用导致大量气体释放,这一过程进一步增加了生物质炭的比表面积[23]。比表面积的增加有助于提高物理吸附效率,而孔隙结构的优化则促进了重金属离子向生物质炭内部的渗透,并与内部的活性位点及官能团发生化学反应,从而增强了生物质炭对重金属离子的化学吸附效能。此外,原始生物质炭的pH高达10.07,这可能是由于在热解过程中酸性官能团的分解以及碱性矿物的析出,使得生物质炭表现出较强的碱性[24]。经过铁基改性后,FC-FMB、FS-FMB、PFS-FMB的pH分别降低至4.72、5.35和5.46,这可能是由于改性后生物质炭表面的三价铁[Fe(Ⅲ)]经过水解作用产生大量氢离子,导致生物质炭的pH降低[25]。铁基改性生物质炭的灰分质量分数均高于原始生物质炭,这可能是因为铁基化合物与生物质炭发生反应,形成了铁氧化物,进而增加了生物质炭的灰分[26]。铁基改性生物质炭总铁质量分数的增加进一步验证了铁材料在生物质炭表面的成功负载。

生物质炭 pH 灰分质

量分数/

(g·kg−1)碳质量

分数/

(g·kg−1)氢质量

分数/

(g·kg−1)总铁质

量分数/

(g·kg−1)比表面积/

(m2·g−1)FMB 10.07 216.03 685.01 27.94 7.89 19.44 FC-FMB 4.72 387.24 435.28 23.58 48.62 84.79 FS-FMB 5.35 421.59 428.45 15.82 41.38 96.01 PFS-FMB 5.46 486.32 380.93 18.44 42.17 101.55 Table 1. Selected physical and chemical properties of the biochars

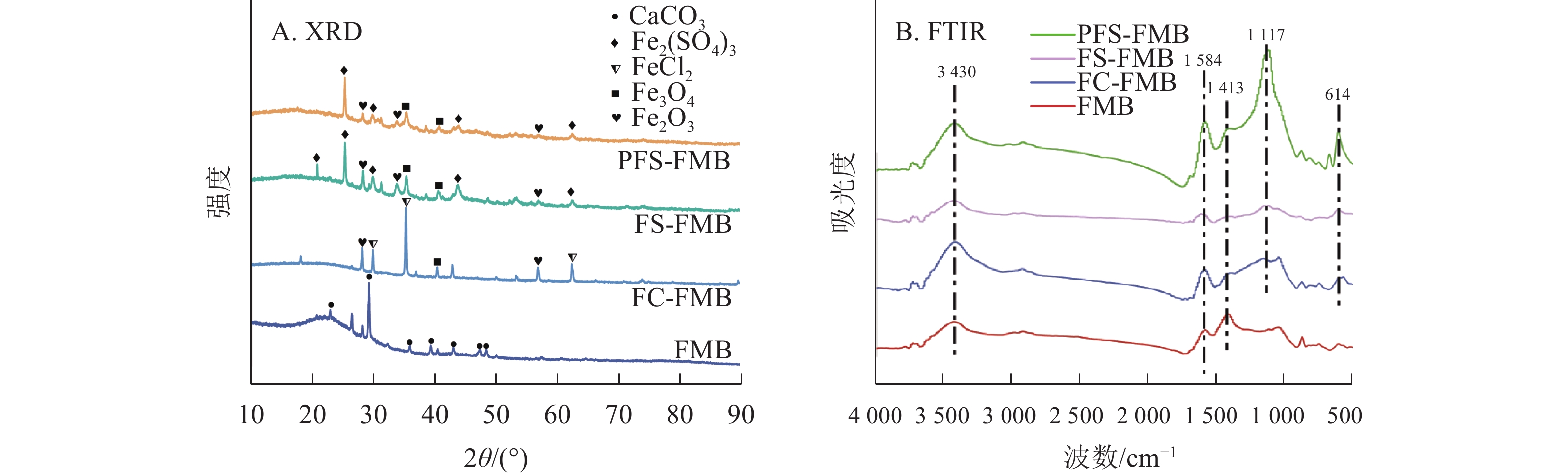

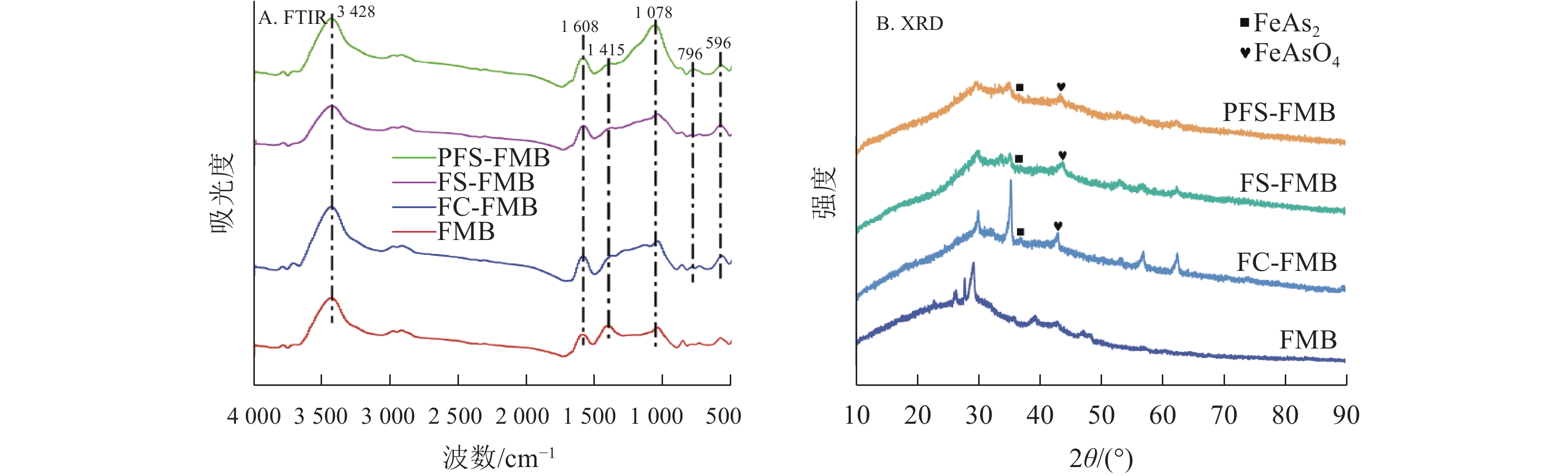

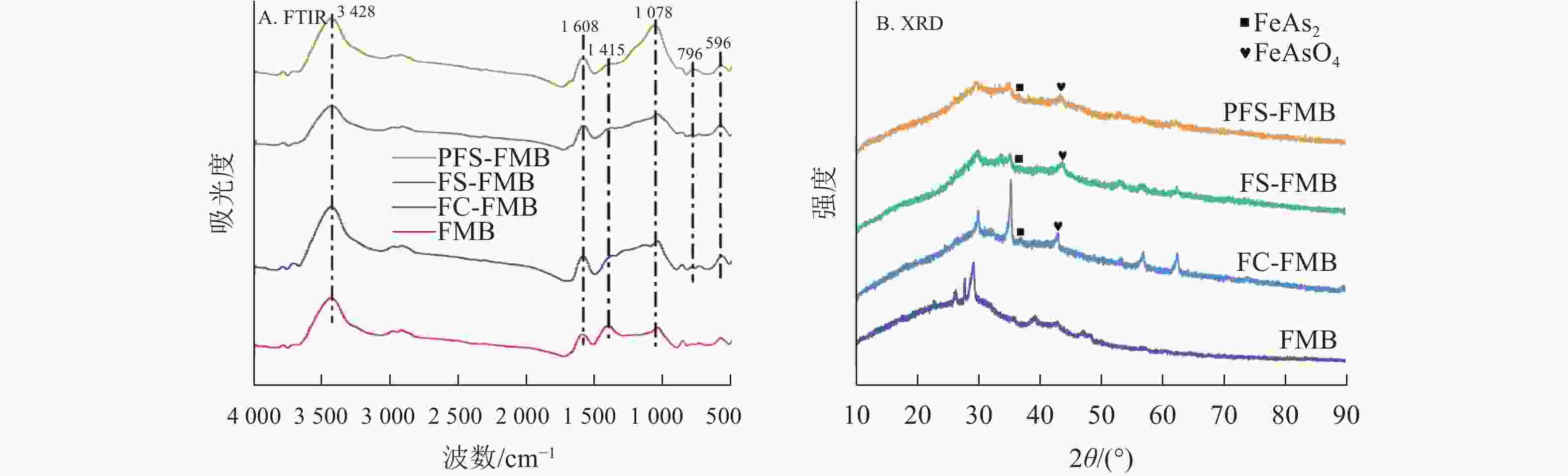

XRD分析结果如图2A所示:细叶榕枝条生物质炭的主要晶体结构为方解石(CaCO3)。在铁基改性生物质炭的衍射图谱中,于25°~45°处均观察到铁氧化物的特征衍射峰。FC-FMB图谱中出现了氯化亚铁(FeCl2)的特征衍射峰,而FS-FMB和PFS-FMB图谱中则显示出Fe2(SO4)3的特征衍射峰。这些特征衍射峰表明,铁基改性材料已成功负载于生物质炭表面。

Figure 2. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) pattern and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) pattern of biochars

图2B表明:生物质炭在改性前后的红外特征峰位置基本保持一致,但峰强存在明显差异。在3 430 cm−1附近观察到的宽峰主要归因于羟基(—OH)的伸缩振动[27]。1 400~1 600 cm−1附近的特征峰则主要由羰基(C=O)的伸缩振动引起,同时包含共轭双键(C=C)的伸缩振动[28]。与FMB相比,铁基改性生物质炭在1 413 cm−1附近的峰强度有所降低,这可能是由于生物质炭在改性过程中发生二次裂解,导致部分含氧官能团的丢失[29]。此外,FS-FMB和PFS-FMB在1 117 cm−1处的峰强度较高,这主要是由于硫酸根(${\mathrm{SO}}_4^{2-} $)在此波数附近具有强烈的红外振动吸收峰[30],这一结果与XRD分析中检测到的Fe2(SO4)3物相一致。PFS-FMB的各个官能团特征峰均较高,这不仅表明其表面含有丰富的官能团,还可能与铁负载过程中引入的高浓度硫酸根对含碳官能团的保护作用有关[31−32]。此外,在614 cm−1附近的吸收峰表明了Fe—O官能团的存在[33],进一步证实了铁基材料已成功负载于生物质炭表面。

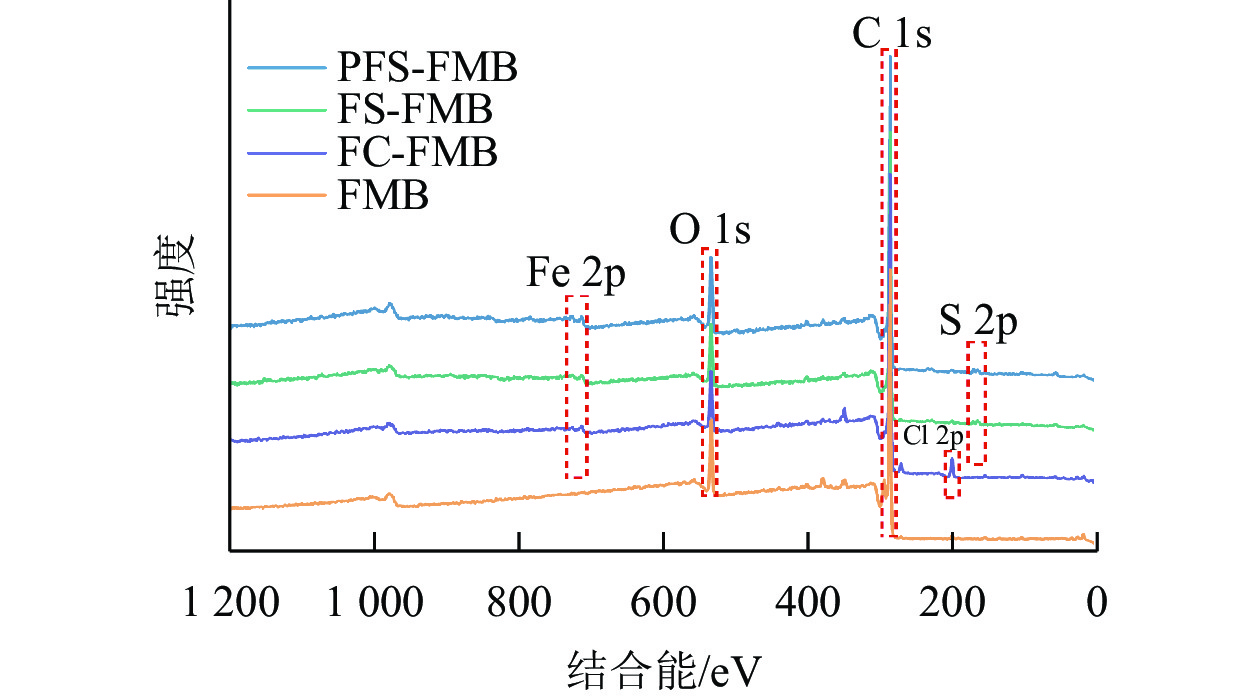

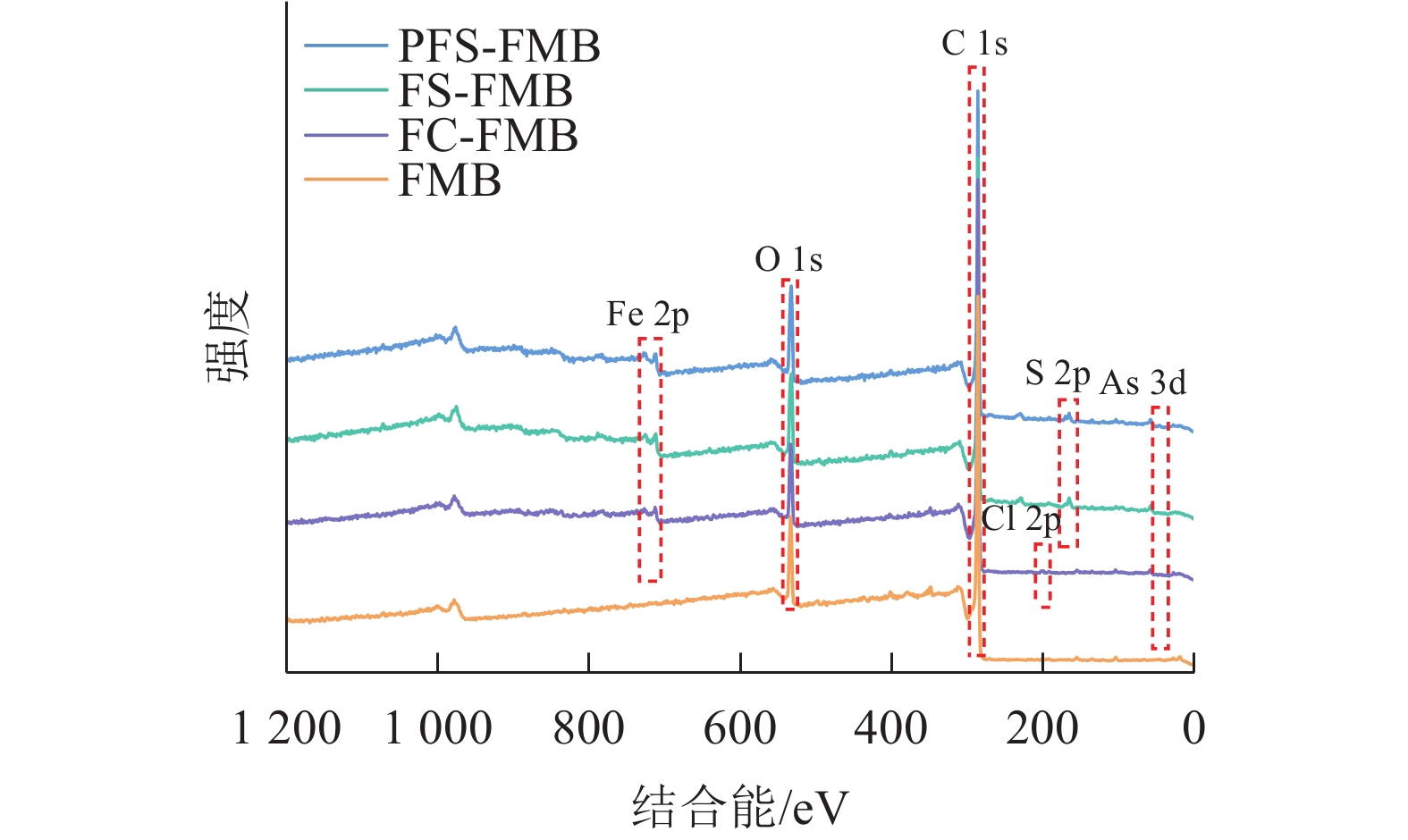

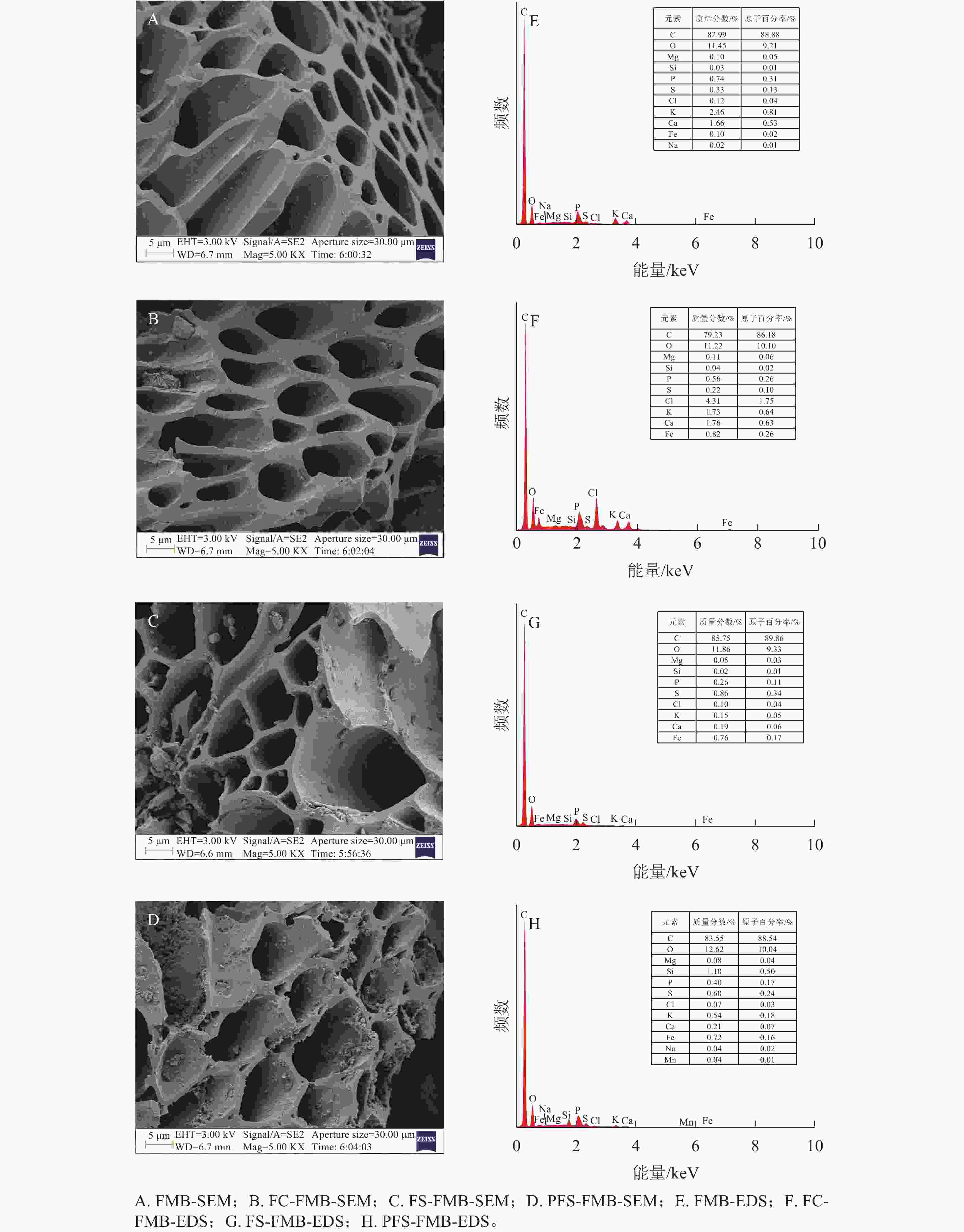

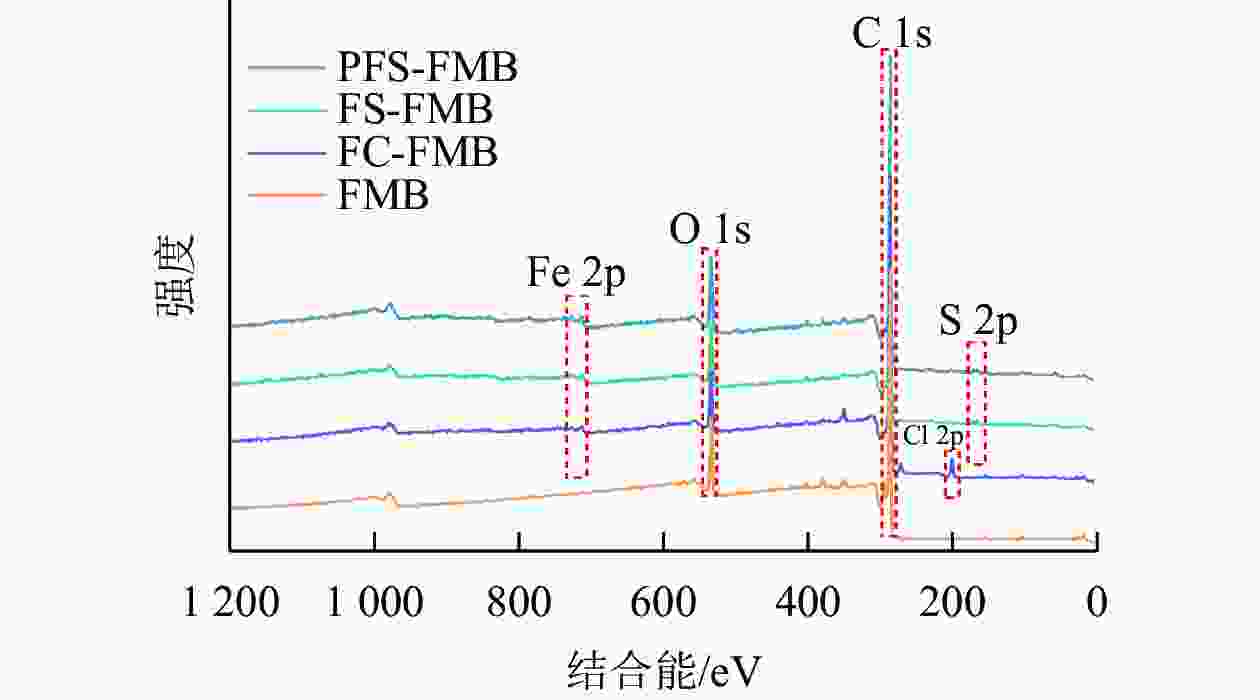

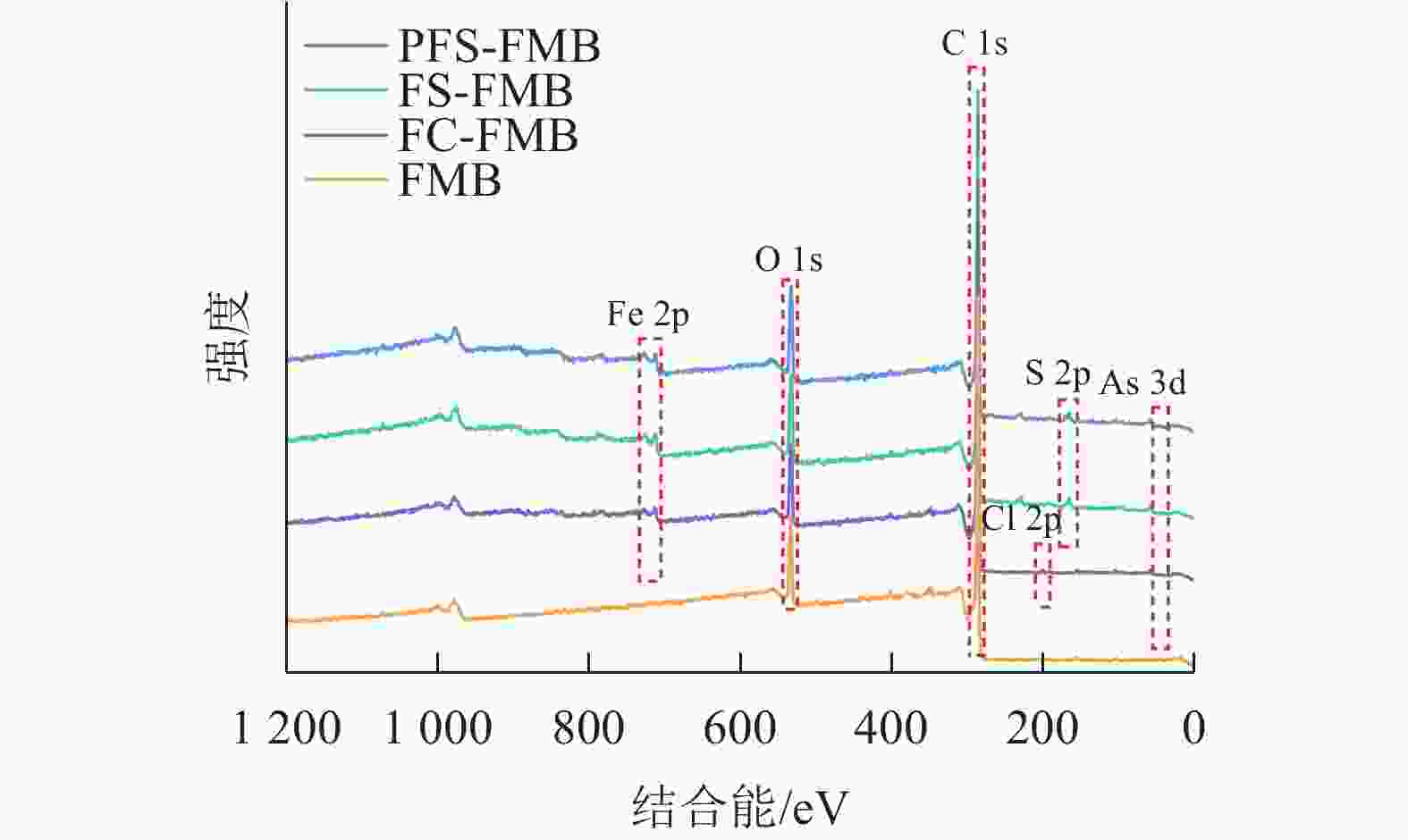

XPS分析结果显示(图3):生物质炭在结合能284.8 eV处检测到C 1s峰,在532.03 eV处检测到O 1s峰。对于铁基改性生物质炭,FC-FMB在200.58 eV处出现了Cl 2p峰,而FS-FMB和PFS-FMB则在163.34 eV处检测到S 2p峰。此外,3种铁基改性生物质炭均在710.87 eV处共同出现了Fe 2p峰。这些特征峰的出现表明,不同改性生物质炭的表面已成功负载了相应的基团,进一步证实了铁基材料及其他改性元素在生物质炭表面的引入。

-

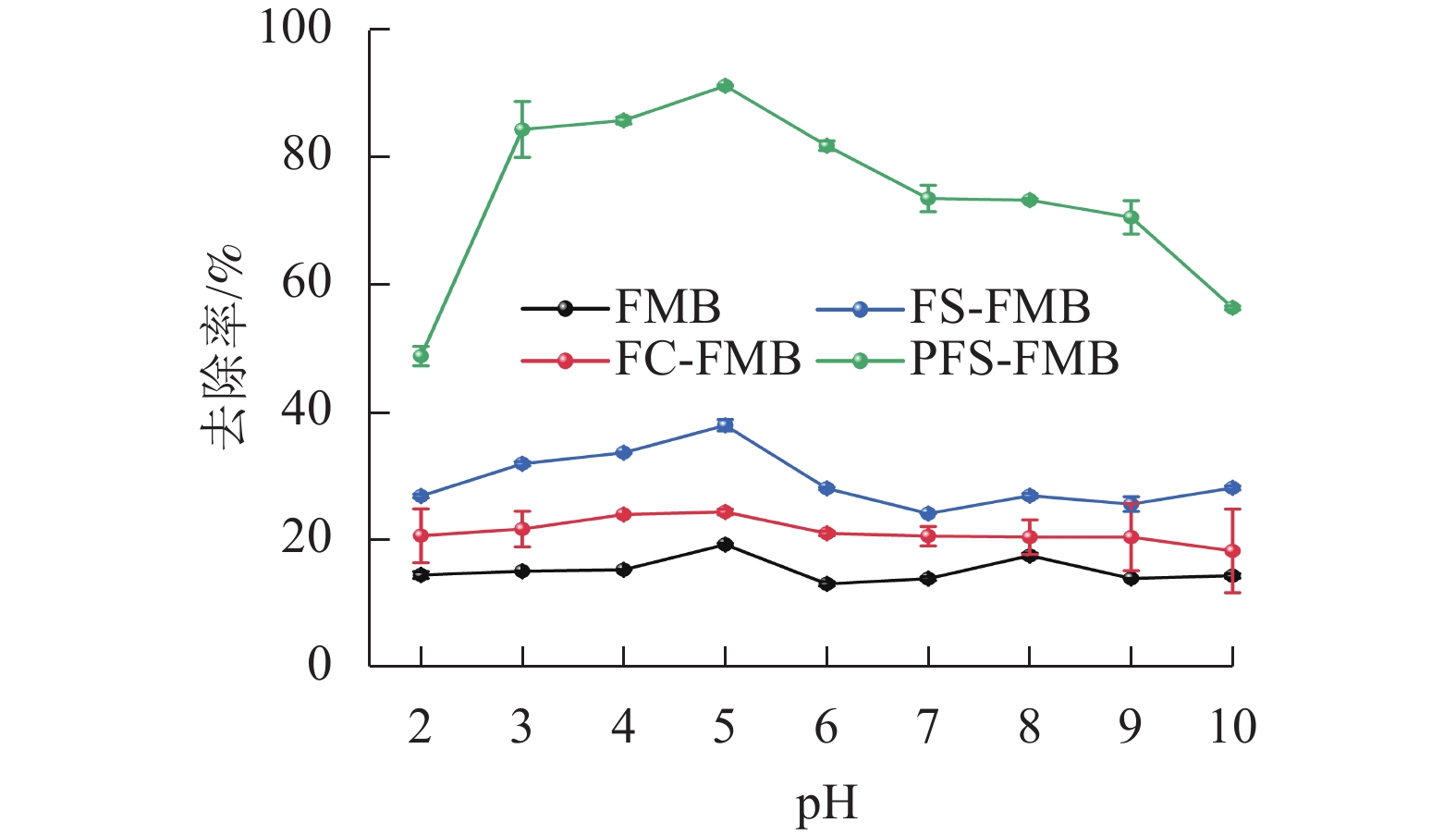

由图4可知:当pH低于5时,4种生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的去除率均随pH升高而增加,并在pH为5时达到最大去除率。然而,当pH高于5时,去除率呈下降趋势。与FMB相比,铁基改性生物质炭在不同pH下对As(Ⅲ)的去除率均有明显提升,其中PFS-FMB的提升最为明显,在pH为5时去除率最高,达到91.16%。在pH低于5时,吸附效果较差,这可能与溶液中较高的Fe(Ⅲ)或Fe(Ⅱ)浓度有关。这些Fe(Ⅲ)或Fe(Ⅱ)可能与As(Ⅲ)在生物质炭表面的活性位点发生竞争吸附,从而减少了As(Ⅲ)的有效吸附位点[34]。当溶液pH高于5时,生物质炭表面负电荷增加,增强了与含砷阴离子之间的静电排斥作用,从而抑制了As(Ⅲ)的吸附。PFS-FMB对As(Ⅲ)的去除率最高,主要归因于其表面含有丰富的羧基(—COOH)和羟基(—OH)等官能团,这些官能团能够与As(Ⅲ)形成稳定的络合物,从而增强吸附能力。此外,PFS-FMB的比表面积和孔隙结构得到了明显优化,进一步增强了其吸附能力。相比之下,FC-FMB的去除率最低,原因在于其改性过程中,Fe主要以FeCl3形式存在,在热解过程中,形成的含氧官能团数量和种类不如另外2种改性生物质炭丰富。同时,FC-FMB的比表面积和孔隙结构相对较小,吸附位点有限,这些因素共同导致了其对As(Ⅲ)的吸附能力较弱。

-

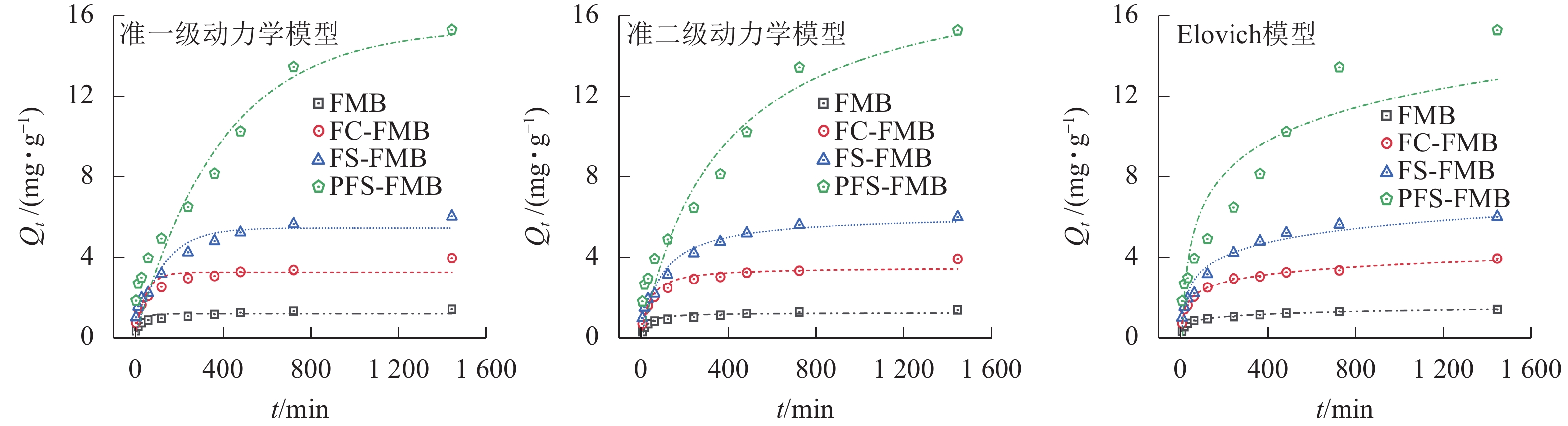

图5表明:生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附过程可分为快速吸附阶段和吸附平衡阶段。除PFS-FMB外,其余生物质炭在前240 min处于快速吸附阶段,吸附量随时间增长明显增加,并在240~480 min逐渐达到吸附平衡。PFS-FMB的快速吸附阶段则持续至480 min,并在此后保持匀速吸附,直至达到吸附平衡。在吸附初始阶段,生物质炭表面丰富的孔隙结构和官能团为As(Ⅲ)提供了大量吸附位点,同时溶液中较高的As(Ⅲ)初始浓度为吸附反应的快速进行提供了动力学优势。随着吸附过程的推进,生物质炭表面的吸附位点逐渐被As(Ⅲ)占据,吸附能力趋于饱和。当达到吸附平衡时,生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附量不再明显增加[35]。PFS-FMB在快速吸附阶段持续时间较长,这主要归因于其较大的比表面积和丰富的表面孔隙通道,使得As(Ⅲ)能够在更长时间内持续占据吸附位点,从而延长了快速吸附阶段。

生物质炭及其改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附过程涉及固相和液相的复杂反应机制。由表2可知:准二级动力学模型和Elovich模型的决定系数(R2)明显高于准一级动力学方程,这表明吸附过程主要受化学吸附机制的控制[36−37]。其中,Elovich模型不仅能够较好地描述4种生物质炭在溶液中的扩散行为,还能揭示其他动力学方程可能忽略的数据不规则性,这一结果反映了吸附过程可能涉及不同活性位点的吸附[23],表明生物质炭吸附As(Ⅲ)的过程中,活化能的变化较大。因此,可以推断生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附是非均相的扩散-吸附过程[38]。

生物质炭 准一级动力学模型 准二级动力学模型 Elovich动力学模型 Qe/(mg·g−1) k1/min−1 R2 Qe/(mg·g−1) k2/(g·mg−1·min−1) R2 α/(g·mg−1·min−1) β/(g·mg−1) R2 FMB 1.204 0.034 0.786 1.297 0.036 00 0.912 0.308 5.366 0.994 FC-FMB 3.256 0.022 0.825 3.548 0.008 00 0.925 0.432 1.811 0.993 FS-FMB 5.462 0.008 0.892 6.159 0.001 90 0.945 0.313 1.015 0.955 PFS-FMB 15.384 0.003 0.903 18.826 0.000 15 0.919 0.085 0.222 0.939 Table 2. Fitting parameters of the kinetic models for the adsorption of As(Ⅲ) by biochar before and after modification

-

从图6和表3可以看出:4种生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附量均随着初始浓度的增加而迅速上升,并最终趋于平衡。Langmuir模型的拟合度优于Freundlich模型,表明生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附过程更符合单分子层吸附机制[39],且吸附位点在生物质炭表面分布均匀[40]。Langmuir模型的拟合结果显示:FMB对As(Ⅲ)的饱和吸附量为1.290 mg·g−1,而FC-FMB、FS-FMB、PFS-FMB的饱和吸附量分别提高至3.111、6.357和13.527 mg·g−1。这一结果表明:改性生物质炭极大增强了对As(Ⅲ)的吸附性能。特别是经过硫铁改性处理的生物质炭在吸附能力上提升更为明显,其中以PFS-FMB的效果最为突出,其饱和吸附量分别是FMB和FC-FMB的10.49和4.35倍。

生物质炭Langmuir模型 Freundlich模型 Qm/(mg·g−1) KL R2 KF/(mg1−N·LN·kg−1) N R2 FMB 1.290 0.059 0.983 0.215 0.364 0.888 FC-FMB 3.111 0.057 0.985 0.478 0.382 0.892 FS-FMB 6.357 0.130 0.993 1.639 0.296 0.889 PFS-FMB 13.527 0.293 0.982 4.486 0.264 0.878 Table 3. Fitting parameters of isothermal adsorption model of As(Ⅲ) by biochars before and after modification

-

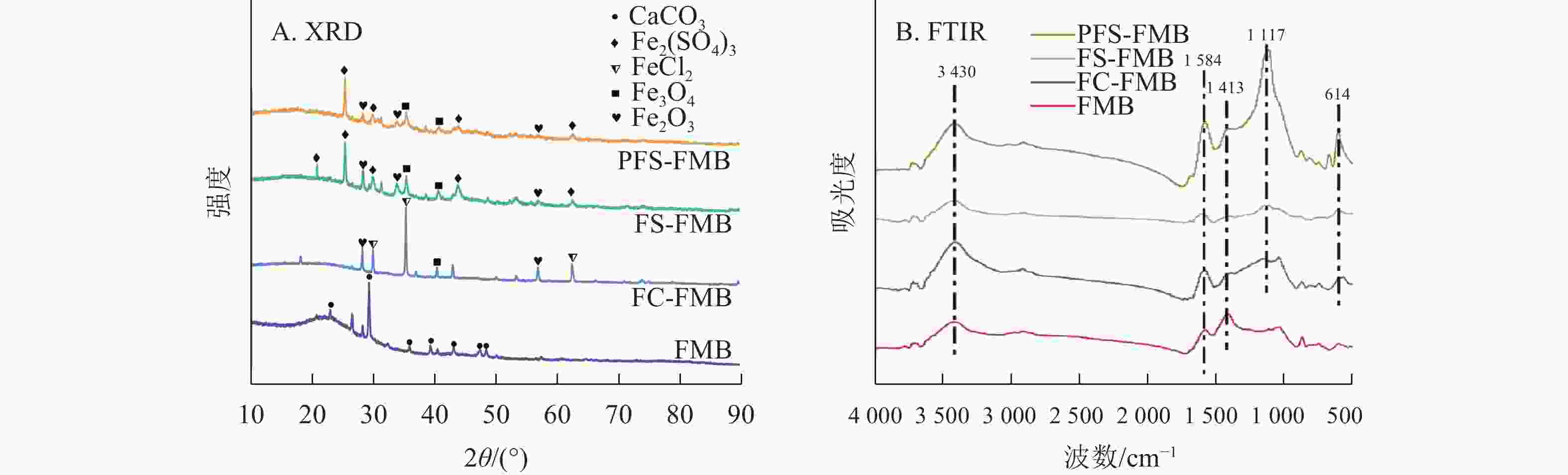

生物质炭吸附As(Ⅲ)后的FTIR分析结果显示(图7A):As(Ⅲ)吸附后,—OH吸收带出现了轻微位移,C—O吸收带在1 078 cm−1处以及Fe—O吸收带在596 cm−1处的强度有所降低。此外,铁基改性生物质炭在796 cm−1处出现了新的吸收峰,该峰归因于As—O—Fe键的振动[41]。这些变化表明:在吸附过程中,生物质炭表面的含氧官能团参与了吸附反应,且Fe—O键的结构发生了变化。As—O—Fe键的形成解释了Fe—O峰的位移现象,并进一步证实了内层络合物的生成[42]。PFS-FMB在796 cm−1处吸收峰强度最大,这与其表现出对As(Ⅲ)的最佳吸附性能相一致。此外,C=O振动带在1 415 cm−1处的变化表明:吸附质可能在生物质炭表面的芳香族化合物上发生了亲电取代反应[43]。这些结果表明:铁基改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附过程不仅涉及表面络合反应,还可能包括生物质炭表面官能团与As(Ⅲ)之间的化学键合。

生物质炭吸附As(Ⅲ)后的XRD图谱(图7B)与原始图谱(图2A)相比,改性生物质炭在吸附As(Ⅲ)后均形成了新的矿物相。由于对As(Ⅲ)的吸附能力较弱,FMB在吸附As(Ⅲ)后未检测到明显的含砷化合物特征峰。相比之下,铁基改性生物质炭在吸附As(Ⅲ)后表现出明显的矿物相变化。首先,检测到了斜方砷铁矿(FeAs2)的存在,这表明共沉淀生成不溶性物质是铁基改性生物质炭去除As(Ⅲ)的重要机制之一。此外,检测到的FeAsO4矿物相进一步证实了Fe与As(Ⅲ)反应生成了低迁移性物质。这一结果表明:铁基改性生物质炭能够通过将As(Ⅲ)氧化为毒性较低的As(Ⅴ),从而实现对As(Ⅲ)的高效去除[44]。

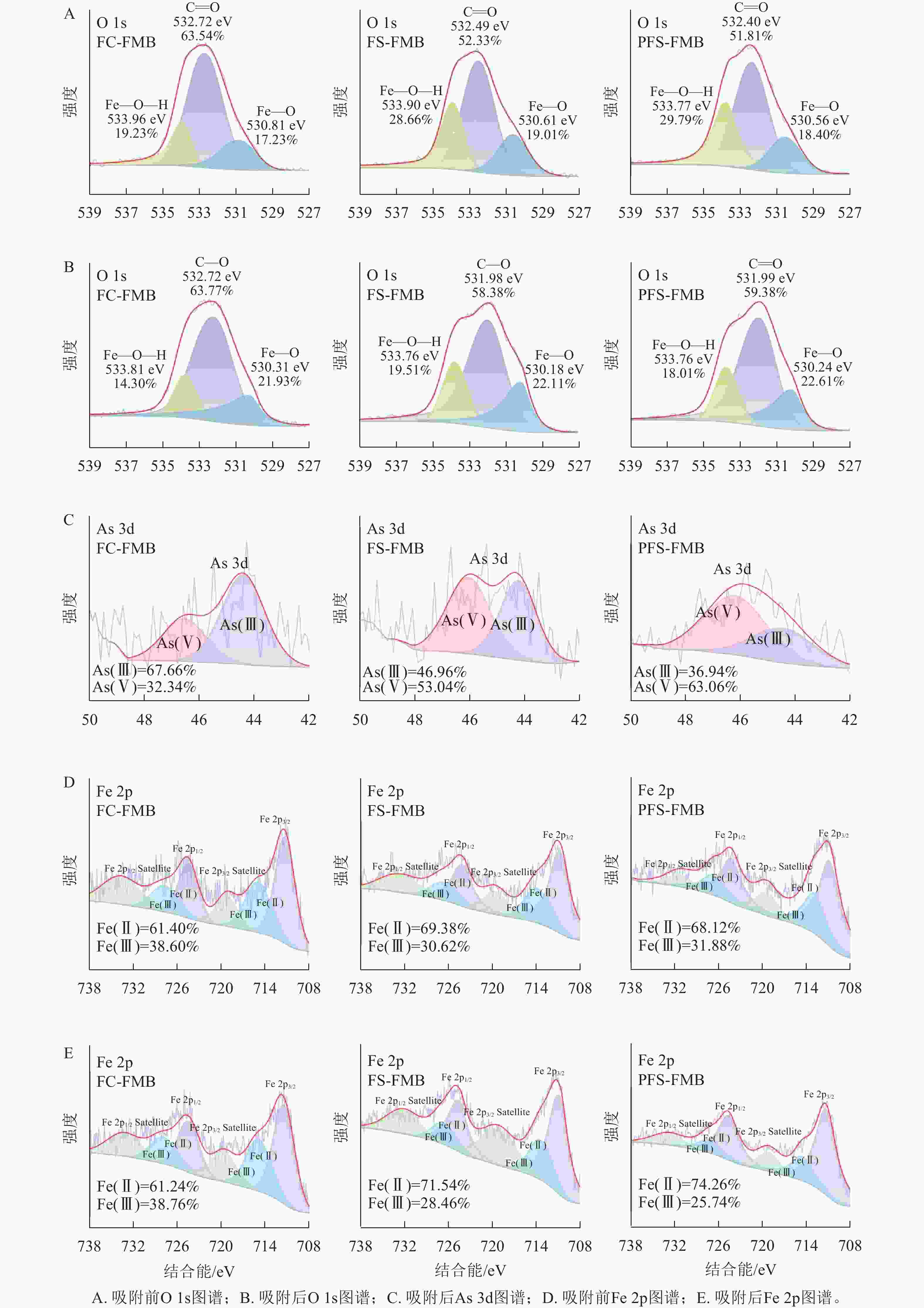

由图8可知:As(Ⅲ)主要通过静电作用和共沉淀作用在生物质炭表面形成吸附[34]。XPS图谱中清晰可见C、O、Fe和As的特征峰,其中吸附后新出现的As 3d峰表明As已成功吸附于生物质炭表面。此外,铁基改性生物质炭的Fe 2p峰向更高结合能方向移动,这可能是由于As—O—Fe结构的形成[45],与吸附后的FTIR分析结果一致。图9A~B中的O 1s光谱解卷积结果显示了530.24、531.99和533.76 eV 3个特征峰,分别对应金属—O、C=O和金属—O—H结构[46]。吸附前生物质炭的O 1s解卷积结果显示:C=O峰的强度高于其他2种含氧结构,表明生物质炭表面以C=O结构为主。吸附后,O存在于金属—O—H结构的比例明显降低,表明Fe—O—H结构在As的吸附过程中发挥了重要作用。同时,Fe—O结构的比例增加,可能是由于形成了Fe—O—As结构[47]。

综上所述,生物质炭吸附后,2个配体原子同时与2个中心金属离子形成配位键,结合FTIR分析中内层络合物的形成,推断As(Ⅲ)与生物质炭之间的结合主要通过双齿双核内球络合机制实现[45]。PFS-FMB的Fe—O—H结构比例最高,其次是FS-FMB,FC-FMB最低(图9A)。由于Fe—O—H结构在As的吸附过程中发挥重要作用,其比例的差异直接影响了改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附能力。这与PFS-FMB对As(Ⅲ)的吸附量最大,而FC-FMB的吸附量在三者中最低的实验结果一致。

XPS分析显示(图9C):生物质炭表面的As(Ⅴ)比例从大到小依次为:PFS-FMB、FS-FMB、FC-FMB。结合先前的吸附实验结果,可以发现随着吸附量的增加,生物质炭表面的As(Ⅴ)比例也随之增加,表明改性生物质炭主要通过氧化As(Ⅲ)实现吸附。Fe 2p谱的解卷积结果显示:Fe(Ⅱ)和Fe(Ⅲ)在改性生物质炭表面共存(图9D~E)。吸附后,Fe(Ⅱ)的峰面积增大,而Fe(Ⅲ)的峰面积相应减少,表明可能发生了氧化还原反应。改性生物质炭在吸附和氧化As(Ⅲ)过程中扮演多重角色,不仅含有能够吸附和固定砷酸盐阴离子的活性基团,还能产生持久自由基和超氧自由基。此外,生物质炭还可以作为Fe(Ⅲ)向Fe(Ⅱ)提供或传递电子的媒介[48−50],研究表明,反应的可能顺序是As(Ⅲ)首先与Fe(Ⅲ)—O—H通过静电吸引结合形成Fe(Ⅲ)—O—H—As(Ⅲ)结构。同时,改性生物质炭表面的一部分Fe(Ⅲ)获得生物质炭转移的电子生成Fe(Ⅱ),释放含氧自由基到水相中,使As(Ⅲ)与含氧自由基反应生成Fe(Ⅱ)—O—H—As(Ⅴ)结构[45]。将改性生物质炭吸附前后的Fe(Ⅱ)和Fe(Ⅲ)峰面积进行对比,发现变化最大的是PFS-FMB,其次是FS-FMB,变化最小的是FC-FMB。这一结果与生物质炭的吸附量呈正相关,进一步证明改性生物质炭是通过氧化As(Ⅲ)实现吸附的。同时,PFS-FMB拥有最大的Fe(Ⅱ)和Fe(Ⅲ)峰面积变化,也证实了PFS-FMB是吸附As(Ⅲ)的最佳改性生物质炭。

-

与FMB相比,改性后生物质炭的铁质量分数均明显增加,其比表面积增大了3.36~4.22倍,含氧官能团的数量也有所增加。溶液pH为5时,改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附效果最佳。Elovich动力学模型和Langmuir等温吸附方程能有效描述生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附行为,对As(Ⅲ)的最大吸附容量从大到小依次为PFS-FMB、FS-FMB、FC-FMB、FMB。铁基改性生物质炭对As(Ⅲ)的吸附方式是以化学吸附为主的表面络合形式,主要吸附机制为砷氧阴离子与铁氧化物的内圈配位效应以及表面羟基官能团的络合作用,其中PFS-FMB对As(Ⅲ)的吸附效果最好。

Adsorption effect and mechanism of different iron-based modified biochar on As(Ⅲ)

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250126

- Received Date: 2025-01-22

- Accepted Date: 2025-05-22

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-05-17

- Available Online: 2026-01-27

- Publish Date: 2026-02-20

-

Key words:

- iron-based modified biochar /

- As(Ⅲ) /

- adsorption mechanism /

- polymerized ferric sulfate

Abstract:

| Citation: | ZHOU Xiaoli, YANG Xing, LU Kouping, et al. Adsorption effect and mechanism of different iron-based modified biochar on As(Ⅲ)[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2026, 43(1): 153−165 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250126 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: