-

随季节变化,植物生长环境中的光照强度、气温等均会发生改变。一般认为,植物光合作用的季节性变化是其对气温的适应性响应[1]。光能和二氧化碳(CO2)分别是光合作用的动力和基本原料,研究光合作用对光强和CO2的响应特征有助于阐明植物在环境变化中的生理生态适应性[2-3]。因此,研究植物光合作用的季节性变化对预测树种响应气候变化引起的气温改变具有重要的意义[4]。研究不同季节植物叶片的气体交换参数(Jmax和Vcmax)、叶绿素含量、叶氮含量及氮分配的变化是揭示植物叶片光合作用季节性变化的生理机制的一种方法[1,5-12]。香榧Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’种籽经炒制后食用,风味香醇,营养价值高,是中国珍稀的上等干果。随着市场需求的增大,从2008年开始,浙江香榧的种植面积迅速增大。截至2019年,浙江省香榧种植面积达4.8万hm2,已成为中国南方山区重要的经济树种[13]。在生产上,通常采用2年生实生榧树Torreya grandis作为砧木嫁接香榧,4~5 a开始挂果,15 a后达盛果期。叶片或树体的生理年龄被认为是评估其对逆境响应能力时需协同考虑的重要因子,因为不同生理年龄的叶片或树体生长对碳源的需求、酶活性、激素活性、水、冠层微环境和叶片的形态结构等均会发生变化[14]。随树龄的增加,树体会由于光合作用/呼吸作用比率降低发生碳饥饿,树体老化[15]。橡树Quercus cerris叶片的光合速率随树龄的增加呈降低趋势[16]。近年来,对于香榧的研究主要集中在药用价值和幼苗与生长环境的关系上[17-19],对香榧不同树龄不同季节叶片光合特性方面的研究国内尚未见报道。本研究以6年生嫁接苗(初挂果期)和16年嫁接苗(盛果期)香榧叶片为研究对象,从表观光合特性和光合内部机构系统地探讨不同树龄香榧叶片光合作用及对气温的响应机制,为制定香榧高效栽培措施提供理论依据。

-

试验区位于浙江省杭州市临安区浙江农林大学香榧基地,29°56′~30°23′N,118°51′~119°52′E,属于亚热带季风气候区,温暖湿润,光照充足,雨量充沛。土壤类型为黄壤土,林地肥料以复合肥为主,配施农家肥。供试材料为16年生和6年生香榧嫁接苗。其中,16年生香榧嫁接苗为2000年采用嫁接苗造林,林分密度为450株·hm−2,砧木为2年生实生榧树,接穗为1年生香榧,平均地径为11.5 cm,平均树高为2.6 m,记为16-a;6年生香榧嫁接苗为2010年采用嫁接苗造林,砧木为2年生实生榧树,接穗为1年生香榧,平均地径为8.3 cm,平均树高为1.8 m,记为6-a。香榧于每年4月底萌发新叶,约50 d叶片生长成为成熟叶[20]。本研究分别以2017年春季(5月)的未成熟叶片、夏季(8月)的成熟叶和秋季(11月)的成熟叶的当年生叶片为材料。

-

气象数据取自杭州市临安区气象局。选择晴朗无风的天气,采用Li-6400便携式光合仪(Licor-6400,Licor,美国),使用可控光簇状叶室(22 L)进行香榧当年生叶片的光响应测定。测定时,叶室内CO2摩尔分数设置为400 μmol·mol−1,由便携式CO2小钢瓶控制CO2摩尔分数;根据气温(5月的最低和最高气温分别为16.2和27.2 ℃;8月分别为21.0和32.5 ℃;11月分别为13.3和24.7 ℃),将5月、8月及11月叶室测定温度分别控制在25、30和20 ℃,叶室的空气相对湿度约50%;采用RGB-18白光光源,设定气体流动速度为500 μmol·s−1。正式记录前,先用800 μmol·m−2·s−1光强对叶片进行光诱导20 min,待叶片活化稳定后,再记录测定数据,记为净光合速率;再将光强调至0 μmol·m−2·s−1,并用黑色布将测定叶室罩住,待稳定后再记录测定数据,记为暗呼吸速率。重复3~5次,取平均值作为测定结果,以上测定均在9:00—11:00完成。

-

成熟香榧叶片的光饱和点为(779.0±71.9) μmol·m−2·s−1[21],因此,对叶片进行CO2响应曲线测定时,光照强度设为800 μmol·m−2·s−1。同时,为模拟生长环境的温度,5月、8月及11月叶室温度分别控制为25、30和20 ℃。在开始CO2响应曲线测定前,先将叶片在CO2摩尔分数为400 μmol·mol−1和光强为800 μmol·m−2·s−1下持续30 min,再依次按不同的CO2摩尔分数(400、300、200、100、50、400、800、1 200、1 600、1 800、2 000 μmol·mol−1)进行净光合速率(Pn)的测定,再将数据通过FARQUHAR等[5]的模型拟合CO2响应曲线。当RuBP充足时,Rubisco是光合速率(Ac)的限制因子,公式如下:

$$ A{\rm{c}} = \frac{{V_{{\rm{c}}\max} (C_{\rm{i}} - {\varGamma ^*})}}{{C_{\rm{i}} + K_{\rm{c}}(1 + O/K_{\rm{o}})}} - R_{\rm{d}} 。 $$ (1) 式(1)中:Vcmax是最大RuBP羧化速率;Kc和Ko是Rubisco羧化作用和加氧作用的Michaelis常数;Ci和O分别为细胞间隙中的CO2和氧气(O2)摩尔分数;Rd是光下的呼吸速率;Г*是不含暗呼吸的CO2补偿点。本研究采用von CAEMMERER等[22]模型中的Rubisco动力学参数进行数据拟合。

当光合速率(Aj)受RuBP更新的限制,可表示为:

$$ A_{\rm{j}} = \frac{{J_{\max} (C_{\rm{i}} - {\varGamma ^*})}}{{4C_{\rm{i}} + 8{\varGamma ^*}}} - R_{\rm{d}} 。 $$ (2) 式(2)中:Jmax是光饱和时用于RuBP再生的光合电子传递速率。通过非线性最小二乘法得到拟合A—Ci曲线,分析得出Vcmax和Jmax。叶片的Vcmax和Rd可根据A—Ci曲线(Ci<250 μmol·mol−1)得出;Jmax则根据A—Ci曲线(Ci>600 μmol·mol−1)获得。

CO2响应曲线的测定在9:00—11:30和14:00—16:00完成。每株树为1个重复,每个处理为5~6个重复。

-

在气体交换测定完成后,收集叶片并带回实验室,将测定枝上的披针叶全部剪下,用透明胶带把叶片粘贴在复印纸上,然后把复印出的针叶剪下称量,叶面积根据单位复印纸的质量计算。随后将叶片放置烘箱,保持85 ℃烘干至恒量,称干质量。比叶重(g·m−2)=干质量/叶面积。

-

采香榧新鲜叶片约0.02 g,剪碎浸入盛有8 mL提取液(体积分数为95%乙醇)的离心管中,密封避光低温浸提至无色[20]。根据用紫外分光光度计(UV 2500,岛津)检测波长在649和664 nm处的吸光度。记录所测叶片的鲜质量和面积,计算叶绿素含量(mg·dm−2)。

-

采香榧叶片,用凯式定氮法[20]测定单位面积上的叶氮含量(NA,g·m−2)。以饱和最大光合速率(Amax)与NA的比值表示光合氮素利用效率(photosynthetic nitrogen utilization efficiency,PNUE)[20]。植物叶氮在光合机构中的分配[12],即分配到Rubisco的氮素(Vcmax/NA)、RuBP再生作用的氮素(Jmax/NA)和捕光组分的氮素(Chl/NA)。

-

用Excel处理数据,通过SigmaPlot 12.5作图,使用Origin 8.0绘制光合—光响应曲线和光合—CO2响应曲线,用SPSS检验显著性差异。

-

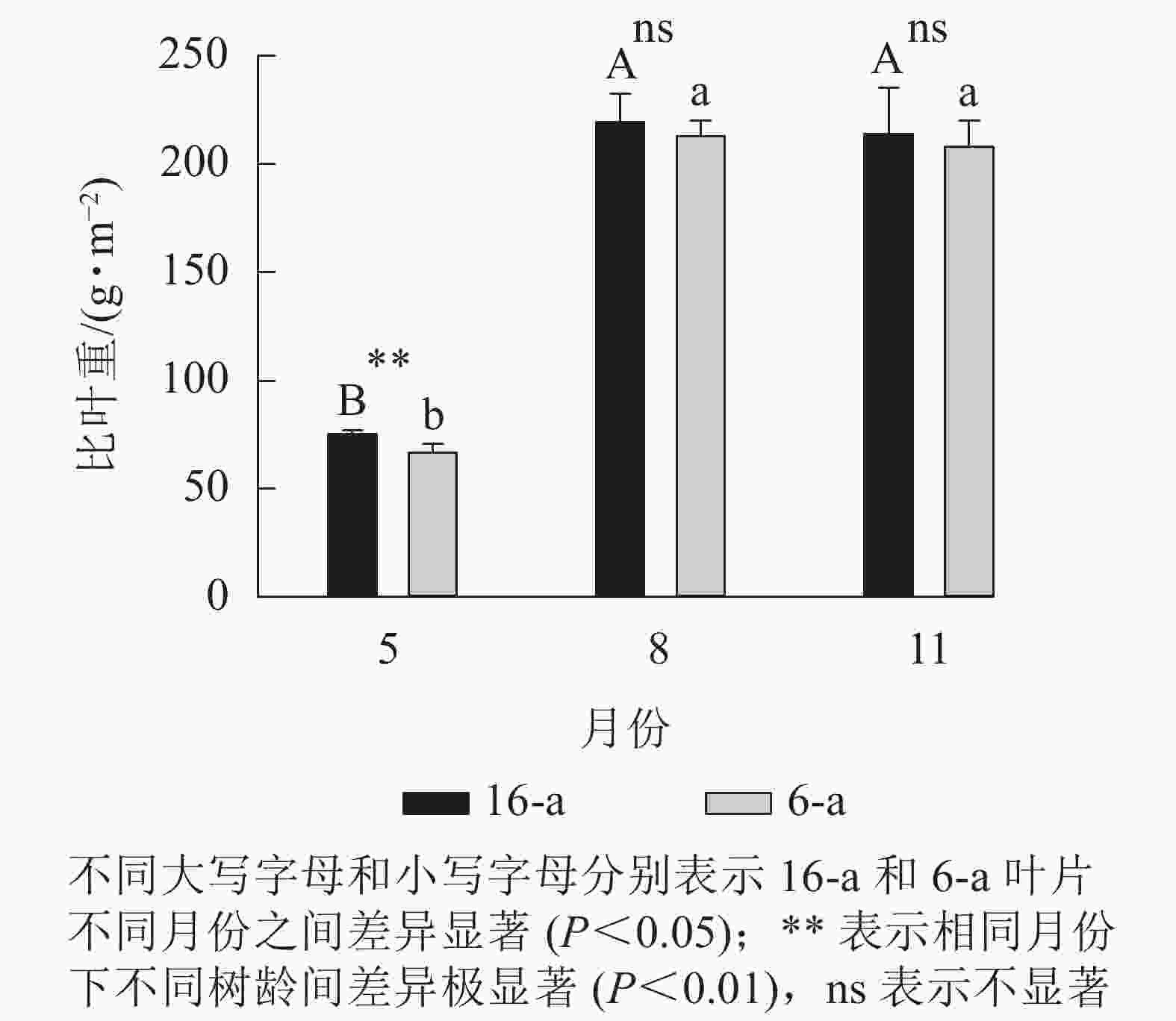

从图1可以看出:无论树龄大小,8月和11月香榧叶片的比叶重显著大于5月香榧叶片的比叶重(P<0.05),8月和11月香榧叶片比叶重之间无显著差异(P>0.05)。5月,16-a的比叶重显著高于6-a(P<0.05);8月和11月,树龄之间的比叶重无显著差异(P>0.05)。

-

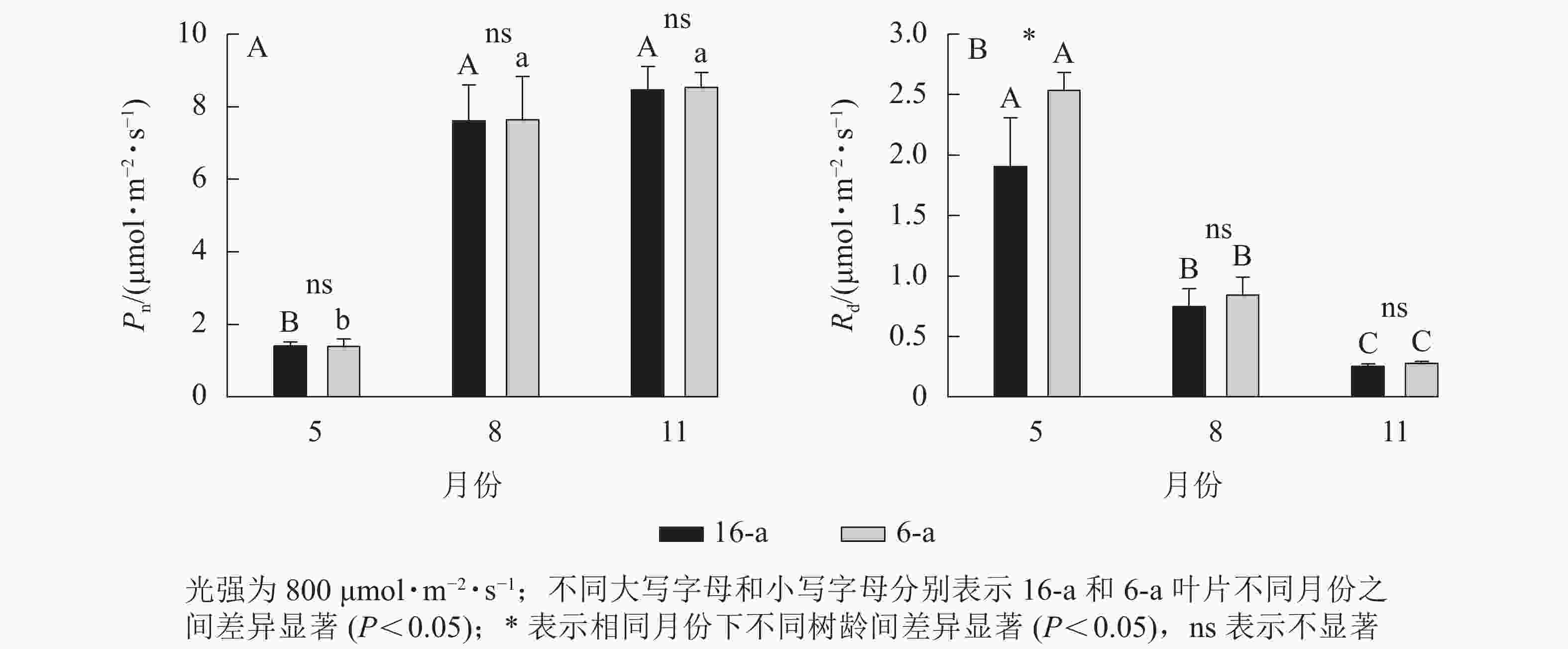

无论树龄大小,香榧叶片的Pn在5月较低,8月快速上升达到峰值,且保持稳定至11月(图2)。5—11月,6-a和16-a香榧叶片的Pn均无显著差异(P>0.05)。5月6-a香榧叶片的Rd显著高于16-a (P<0.05),但8—11月两者之间无显著差异(P>0.05)。

-

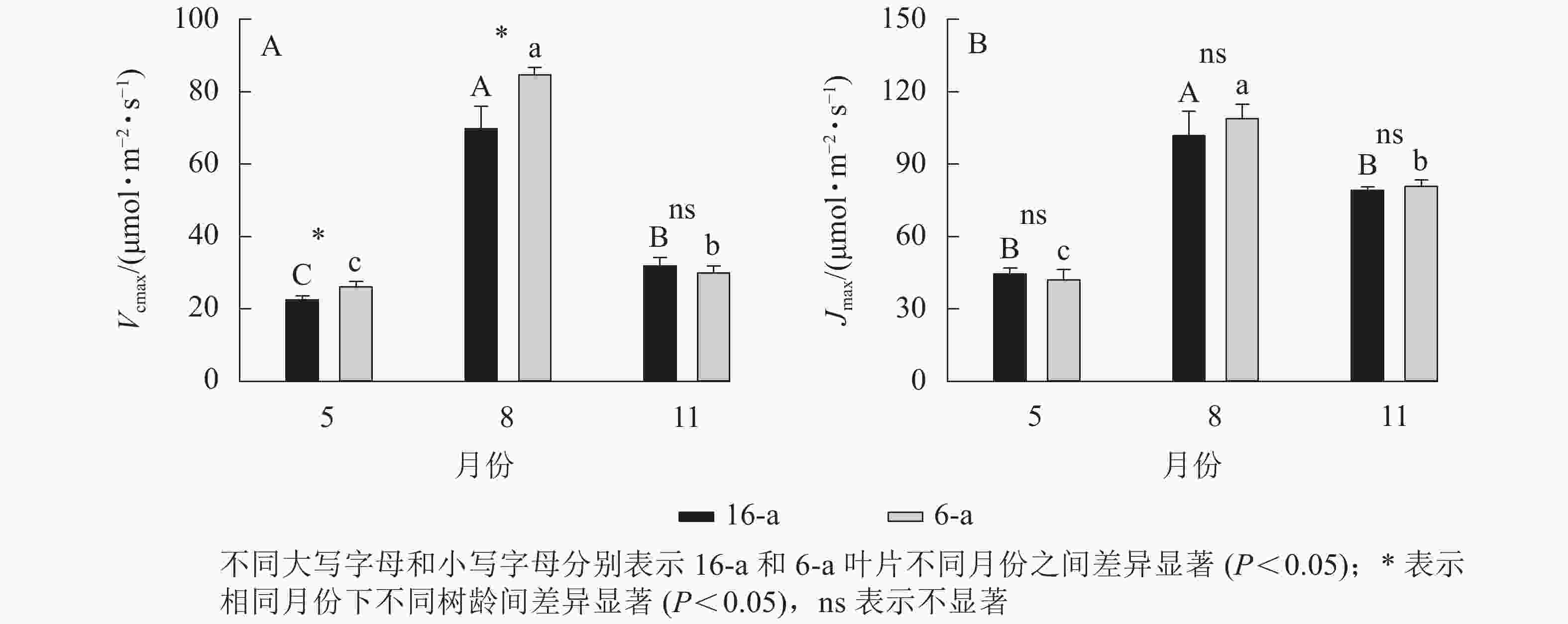

由图3可知:无论树龄大小,11月香榧叶片的CO2饱和点显著高于8月(P<0.05);8月时,16-a和6-a香榧叶片的CO2饱和点分别为725和550 μmol·mol−1,11月时分别为740和1075 μmol·mol−1。由图4可知:无论树龄大小,5月香榧叶片的Vcmax和Jmax均显著低于8月和11月(P<0.05)。与8月相比,11月16-a和6-a的Vcmax分别降低了54.4%和64.6%,而Jmax分别降低了22.1%和25.8%。

-

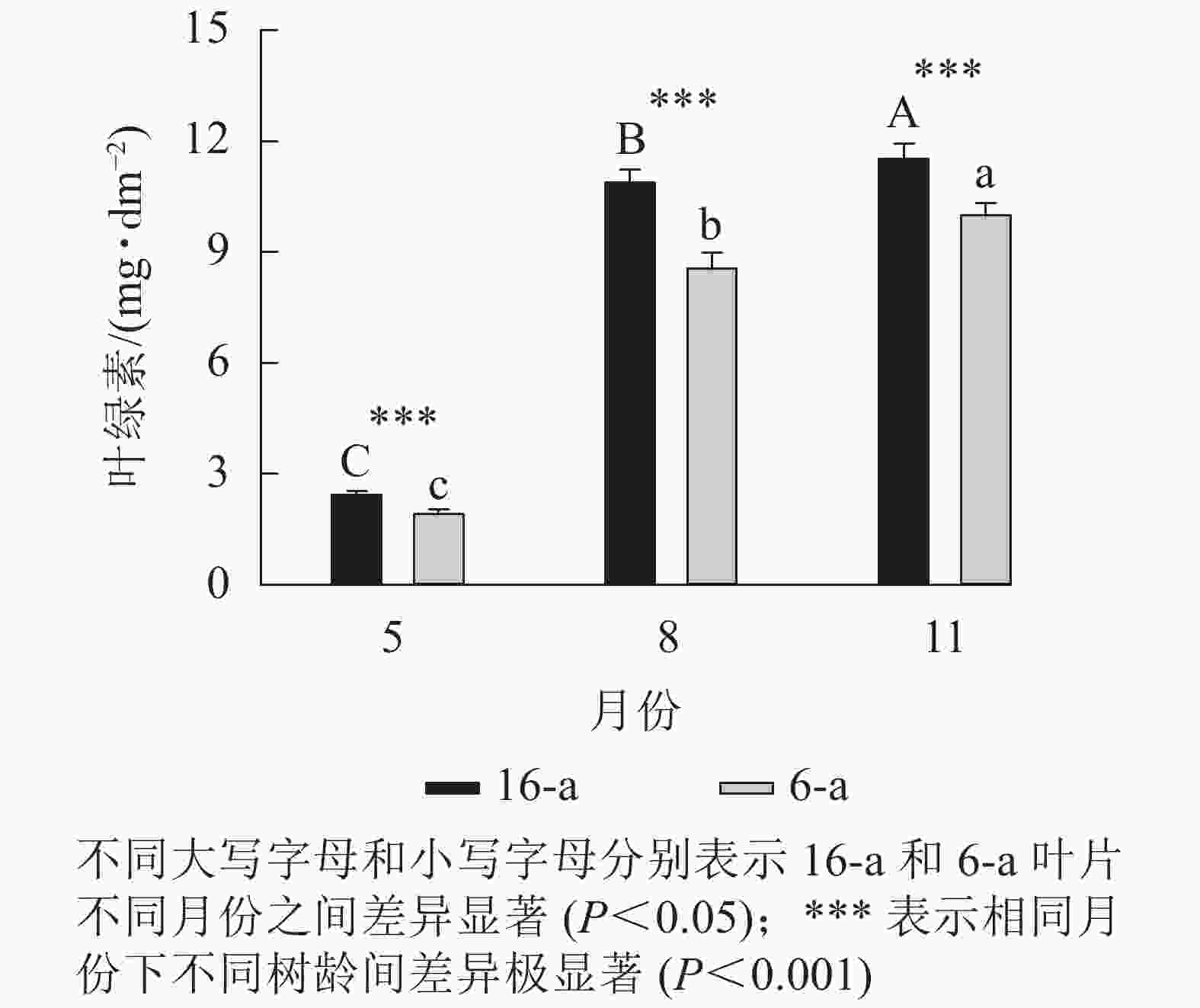

图5显示:无论树龄大小,5月香榧叶片的叶绿素含量显著高于8和11月(P<0.05),且16-a香榧叶片的叶绿素含量均极显著高于6-a香榧叶片的叶绿素含量(P<0.001)。

-

由图6可见:无论树龄大小,与5月相比,8月16-a和6-a香榧叶片的氮含量分别下降了23.8%和17.6%,差异显著(P<0.05);与8月相比,11月16-a和6-a香榧叶片的氮含量均增加了11.0%,差异显著(P<0.05);且6-a香榧叶片的PNUE均极显著高于16-a (P<0.001);其中8月和11月时,6-a香榧叶片的PNUE分别为16-a香榧叶片的1.14和1.20倍。

图 6 不同月份不同树龄单位面积上的香榧叶片氮含量(NA)和光合氮素利用效率(PNUE)的变化

Figure 6. Changes in nitrogen content per area (NA) and photosynthetic nitrogen utilization efficiency (PNUE) in leaves of T. grandis‘Merrillii’ at different tree ages among different months

由表1可见:无论树龄大小,与5月相比,8月香榧叶片的Jmax/Vcmax显著降低(P<0.05);而与8月相比,11月香榧叶片的Jmax/Vcmax显著增加(P<0.05)。5月和8月时,16-a香榧叶片的Jmax/Vcmax显著高于6-a (P<0.05)。无论树龄大小,与5月相比,8月香榧叶片的Jmax/NA、Vcmax/NA和Chl/NA均显著增加(P<0.05);与8月相比,11月的16-a和6-a的Jmax/NA分别降低了30.1%和29.4%,而Vcmax/NA分别降低了60.9%和67.8%,而Chl/NA无显著变化(P>0.05)。

表 1 不同月份不同树龄香榧叶片Jmax/Vcmax、Jmax/NA、Vcmax/NA和Chl/NA的变化

Table 1. Changes in Jmax/Vcmax, Jmax/NA, Vcmax/NA and Chl/NA in leaves of T. grandis ‘Merrillii’ at different tree ages among different months

月份 不同树龄 Jmax/Vcmax Jmax/NA

/(μmol·g−1·s−1)Vcmax/NA

/(μmol·g−1·s−1)Chl/NA

/(μg·g−1)5 16-a 1.98±0.03 B** 22.65±1.24 Cns 11.45±0.80 C* 12.3±0.06 Cns 6-a 1.61±0.08 b 25.47±2.60 c 15.80±0.88 c 11.6±0.07 b 8 16-a 1.46±0.01 C* 67.98±6.76 Ans 48.74±1.12 A** 78.0±0.22 A*** 6-a 1.29±0.05 c 77.37±2.54 a 62.07±1.49 a 62.7±0.32 a 11 16-a 2.59±0.27 Ans 47.50±0.88 B* 19.06±1.48 Bns 70.2±0.02 B** 6-a 2.70±0.09 a 54.61±1.82 b 19.96±1.31 b 65.5±0.13 a 说明:不同大写字母和小写字母分别表示16-a和6-a叶片不同月份之间差异显著(P<0.05);*、**、***和ns分别表示相同月份下不同 树龄间差异显著(P<0.05)、极显著(P<0.01)、极显著(P<0.001)和不显著 -

植物干物质的90%~95%来源于光合作用。本研究结果显示:5月时,16-a香榧叶片的比叶重显著高于6-a叶片的,而此时16-a与6-a香榧叶片的Pn之间无显著差异,但6-a香榧叶片的Rd则明显大于16-a香榧叶片,这可能是由于呼吸消耗相对较低的16-a香榧叶片更有利用干物质的积累,可为盛果期的丰产提供较多的物质基础。5和8月时,16-a和6-a香榧叶片的SLW均增至最大,这与其快速增长的Pn、太阳总辐射和日照长度的增长密切相关。杭州地区8月的太阳总幅射和日照时数均明显多于5月[23]。

本研究结果显示:与5月相比,无论树龄大小,8月香榧叶片的Pn和SLW均明显增大;但8月香榧叶片的NA均显著降低,这可能是由于叶片光合作用增强,碳水化合物快速积累,而使其叶片中的氮含量被稀释了[9-10]。有研究表明:随着山胡椒属Lindera植物Lindera umbellate落叶植物叶片的衰老,叶片中可代谢的氮素(如光合相关蛋白质)会降解成可再利用的氮素[24],再转移至其他发育的器官中[25]。无论树龄大小,与8月相比,11月香榧叶片的Pn略有上升,且NA显著增加,表明当年生的香榧叶片并未启动衰老过程,其所增加的叶片氮含量可能来源于其他多年生衰老的叶片。这与赵雨馨[26]的研究结果相一致,12月香榧叶片光合速率显著高于7和10月。无论哪个月份,16-a香榧叶片的NA均显著高于6-a香榧叶片的,但其PNUE却均显著低于6-a香榧叶片的,表明在生产上须注意氮肥的施用,尤其是像16-a这种进入盛果期的香榧。通常,叶片中50%以上的氮素分配到光合作用相关的蛋白质中,如Rubisco、捕光蛋白等[8]。有研究表明:Vcmax的降低通常是由于Rubisco含量的减少[27]或Rubisco活化位点降低[28]。矮垂头菊Daphniphyllum humile当年生叶片的氮含量、Rubisco含量随季节变化(从春季到秋季)呈逐渐增加的趋势,但其叶片的饱和光合速率稳定不变[9]。本研究结果显示:无论树龄大小,与8月相比,11月香榧叶片SLW、Pn无显著变化,而其NA均显著增加,但Vcmax均显著降低,表明当年生的香榧叶片Vcmax的降低可能是Rubisco活化位点的减少引起的。8月时,6-a香榧叶片的Vcmax显著高于16-a香榧叶片的,但两者之间的Amax无显著差异,这可能是由于其Rubisco未完全激活,仅起着储存氮素的作用[29]。已有研究表明:相比较易招引昆虫的氨基酸形式的氮素形态,Rubisco是更好的氮素储存形式[30]。

与20世纪相比,大气CO2摩尔分数和温度均明显升高,且未来还将会持续升高[31-32]。本研究结果显示:无论树龄大小,香榧叶片的CO2饱和点均大于500 μmol·mol−1,表明香榧叶片的光合作用在当今大气的CO2摩尔分数下仍未达到饱和,对高摩尔分数CO2有一定的适应性,这可能也是香榧的结果期可达百年甚至千年的原因之一。研究表明:Jmax/Vcmax可以指示RuBP再生作用和羧化作用2个过程的相关蛋白质的分配情况[33-34]。本研究结果显示:无论树龄大小,随温度的降低(8—11月),香榧叶片的Jmax/Vcmax均明显增大,这与前人的研究结果一致[7, 35]。当光合速率处于受RuBP羧化作用限制的阶段(Ac)时,碳同化对温度的变化不太敏感,由于低温下光呼吸也受抑制,有利于促进CO2的羧化固定,降低的光呼吸消耗从一定程度上弥补了低温引发减弱的RuBP羧化作用[36],而当光合速率受RuBP再生作用限制的阶段(Aj),其碳同化较易受到低温的影响[36-37],因此,在高CO2摩尔分数下,温度对其光合碳同化的影响远大于其在低CO2摩尔分数下的影响。由此可知,较低温下(与8月相比,11月香榧苗木生长的环境温度约下降了10 ℃以上),香榧叶片通过Jmax的相对增加(下降幅度相对较小)来缓减低温对RuBP再生作用的影响,即植物通过改变Jmax/Vcmax来调整Ac和Aj之间的失衡状态[37-38]。

此外,调整氮素在光合机构的分配常被认为是植物适应温度变化的重要机制[11]。本研究结果显示:随着气温的降低(8—11月),香榧叶片分配到Rubisco的氮素(Vcmax/NA)显著减少,其下降幅度明显大于分配到其他光合蛋白的氮素(Jmax/NA和Chl/NA)。这可能是由于不同光合蛋白的理化性质引起的,即Rubisco是一种可溶性蛋白,而反应中心和捕光蛋白(如LHCII)是类囊体膜蛋白,因此,Rubisco中氮素再利用效率明显高于其他捕光蛋白(如LHCII)中的氮素。有研究表明:在高CO2摩尔分数下,如果将氮素相对较少地分配到Rubisco,且相对较多地分配到RuBP再生作用相关的光合蛋白上,则会大大提高氮素的光合利用效率[37, 39]。本研究结果显示:随着气温的降低(8—11月),6-a香榧叶片Vcmax/NA的下降幅度明显大于16-a叶片的,而6-a与16-a香榧叶片Jmax/NA的下降幅度相差不多,因此,低温下(11月),6-a香榧叶片分配到RuBP羧化作用的氮素较少和分配到RuBP再生作用的氮素较多是其叶片PNUE相对较高的原因。此外,香榧是一种长寿的经济树种,是否能通过调控氮素在光合组分中的分配来适应逐渐变暖、CO2摩尔分数持续上升的全球气候变化?因此,未来应该重点研究香榧古树与新种植的香榧树对温度和CO2摩尔分数倍增变化的适应性是否存在差异。

Changes of photosynthesis in leaves of Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’ in different months and different tree ages

-

摘要:

目的 研究不同树龄香榧Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’叶片光合作用季节性变化的生理机制,为香榧苗木的高效栽培和香榧产业的可持续发展提供理论支持。 方法 分别在5、8和11月测定不同树龄(6和16年生嫁接苗,分别记为6-a和16-a)香榧叶片的叶绿素、二氧化碳(CO2)的响应曲线、单位面积上的叶片氮含量(NA)和光合氮素利用效率(PNUE)等,系统地分析比较表观光合特性和光合内部结构的变化。 结果 5月和8月,无论树龄大小,香榧叶片的净光合速率(Pn)、比叶重(SLW)、最大RuBP羧化速率(Vcmax)、光饱和时用于RuBP再生的光合电子传递速率(Jmax)、总叶绿素含量(Chl)及分配到Rubisco的氮素(Vcmax/NA)、RuBP再生作用的氮素(Jmax/NA)和捕光色素组分的氮素(Chl/NA)均显著增加,而NA则显著降低。无论树龄大小,与8月相比,11月香榧叶片Chl、叶片氮含量和Jmax/Vcmax比值均显著增加,而Vcmax、Jmax、Vcmax/NA、Jmax/NA和Chl/NA均显著降低,Amax和SLW则无显著变化。8月和11月,6-a香榧叶片的Vcmax/NA下降幅度显著大于16-a叶片的,而6-a与16-a香榧叶片Jmax/NA的下降幅度相当。5、8和11月,6-a香榧叶片的PNUE均显著高于16-a叶片的。 结论 从5月至8月,无论树龄大小,香榧叶片的光合能力逐渐增强,干物质不断的积累,从而稀释了其叶片中的氮含量,叶片发育成熟;从8—11月(随温度的降低),无论树龄大小,香榧叶片未发生衰老,但其氮素在各光合组分中的分配比例发生变化,即通过Jmax的相对增加来缓减低温对RuBP再生作用的影响。随温度的降低,6-a香榧叶片分配到RuBP羧化作用的氮素较少和分配到RuBP再生作用的氮素较多,可能是导致其叶片PNUE相对较高的原因。图6表1参39 Abstract:Objective This study aims to investigate the physiological mechanism of seasonal changes of photosynthesis of Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’ leaves at different tree ages, so as to provide theoretical support for the efficient cultivation and sustainable development of T. grandis ‘Merrillii’ industry. Method The response curves of chlorophyll and CO2, leaf nitrogen content per unit area (NA) and photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency (PNUE) in leaves of T. grandis ‘Merrillii’ at different tree ages (6 and 16-year-old grafted trees, named as 6-a and 16-a respectively) were measured in May, August and November. The changes of surface photosynthetic characteristics and internal structure of photosynthesis were systematically analyzed and compared. Result In May and August, net photosynthetic rate (Pn), specific leaf weight (SLW), maximum RuBP carboxylation rate (Vcmax), photosynthetic electron transfer rate for RuBP regeneration (Jmax), total chlorophyll content (Chl), nitrogen allocated to Rubisco (Vcmax/NA), nitrogen for RuBP regeneration (Jmax/NA), and nitrogen for light harvesting pigment components (Chl/NA) in leaves increased significantly regardless of tree age, while NA decreased significantly. Regardless of tree age, Chl content, leaf nitrogen content and Jmax/Vcmax ratio in leaves increased significantly in November compared with those in August, while Vcmax, Jmax, Vcmax/NA, Jmax/NA, and Chl/NA decreased significantly. There was no significant change in Amax and SLW. The decrease of Vcmax/NA in 6-a leaves was significantly greater than that in 16-a leaves, while the decrease of Jmax/NA and Chl/NA in 6-a and 16-a leaves was the same. The PNUE of 6-a leaves was significantly higher than that of 16-a leaves in May, August and November. Conclusion From May to August, regardless of tree age, the photosynthetic capacity of leaves gradually enhances, and dry matter accumulates continuously, which significantly dilutes the nitrogen content and makes the leaves mature. From August to November (with the decrease of temperature), leaf senescence never occurs. However, the nitrogen distribution proportion in photosynthetic components changes, that is, the effect of low temperature on RuBP regeneration is mitigated by the relative increase of Jmax. With the decrease of temperature, 6-a leaves allocate less nitrogen to RuBP carboxylation and more nitrogen to RuBP regeneration, which may be the reason for the relatively high PNUE of 6-a leaves. [Ch, 6 fig. 1 tab. 39 ref.] -

Key words:

- tree ages /

- Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’ /

- light response curve /

- CO2 response curve

-

表 1 不同月份不同树龄香榧叶片Jmax/Vcmax、Jmax/NA、Vcmax/NA和Chl/NA的变化

Table 1. Changes in Jmax/Vcmax, Jmax/NA, Vcmax/NA and Chl/NA in leaves of T. grandis ‘Merrillii’ at different tree ages among different months

月份 不同树龄 Jmax/Vcmax Jmax/NA

/(μmol·g−1·s−1)Vcmax/NA

/(μmol·g−1·s−1)Chl/NA

/(μg·g−1)5 16-a 1.98±0.03 B** 22.65±1.24 Cns 11.45±0.80 C* 12.3±0.06 Cns 6-a 1.61±0.08 b 25.47±2.60 c 15.80±0.88 c 11.6±0.07 b 8 16-a 1.46±0.01 C* 67.98±6.76 Ans 48.74±1.12 A** 78.0±0.22 A*** 6-a 1.29±0.05 c 77.37±2.54 a 62.07±1.49 a 62.7±0.32 a 11 16-a 2.59±0.27 Ans 47.50±0.88 B* 19.06±1.48 Bns 70.2±0.02 B** 6-a 2.70±0.09 a 54.61±1.82 b 19.96±1.31 b 65.5±0.13 a 说明:不同大写字母和小写字母分别表示16-a和6-a叶片不同月份之间差异显著(P<0.05);*、**、***和ns分别表示相同月份下不同 树龄间差异显著(P<0.05)、极显著(P<0.01)、极显著(P<0.001)和不显著 -

[1] SILVA E A, DAMATTA F M, DUCATTI C, et al. Seasonal changes in vegetative growth and photosynthesis of Arabica coffee trees [J]. Field Crops Res, 2004, 89(2/3): 349 − 357. [2] XIA Jiangbao, ZHANG Shuyong, ZHANG Guangcan, et al. Critical responses of photosynthetic efficiency in Campsis radicans (L. ) seem to soil water and light intensities [J]. Afr J Biotechnol, 2011, 10(77): 17748 − 17754. [3] VONGCHAROEN K, SANTANOO S, BANTERNG P, et al. Seasonal variation in photosynthesis performance of cassava at two different growth stages under irrigated and rain-fed conditions in a tropical savanna climate [J]. Photosynthetica, 2018, 56(4): 1398 − 1413. [4] MEDLYNE B E, LOUSTAU D, DELZON S. Temperature response of parameters of a biochemically based model of photosynthesis (Ⅰ) Seasonal changes in mature maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.) [J/OL]. Plant Cell Environ, 2002, 25(9) [2021-03-04]. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00890.x. [5] FARQUHAR G D, CAEMMERER S V, BERR J A. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species [J]. Planta, 1980, 149(1): 78 − 90. [6] MURAOKA H, KOIZUMI H. Photosynthetic and structural characteristics of canopy and shrub trees in a cool-temperate deciduous broadleaved forest: implication to the ecosystem carbon gain [J]. Agric Fort Meteorol, 2005, 134(1/4): 39 − 59. [7] ONODA Y, HIKOSAKA K, HIROSE T. Seasonal change in the balance between capacities of RuBP carboxylation and RuBP regeneration affects CO2 response of photosynthesis in Polygonum cuspidatum [J]. J Exp Bot, 2005, 56(412): 755 − 763. [8] MAKINO A. Rubisco and nitrogen relationships in rice: leaf photosynthesis and plant growth [J]. Soil Sci Plant Nutr, 2003, 49(3): 319 − 327. [9] MIGLIETTA C K. Long term effects of naturally elevated CO2 on Mediterranean grassland and forest trees [J]. Oecologia, 1994, 99: 343 − 351. [10] ONODA Y, HIROSE T, HIKOSAKA K. Effect of elevated CO2 levels on leaf starch, nitrogen and photosynthesis of plants growing at three natural CO2 springs in Japan [J]. Ecol Res, 2007, 22: 475 − 484. [11] KATAHATA S, NARAMOTO M, KAKUBARI Y, et al. Seasonal changes in photosynthesis and nitrogen allocation in leaves of different tree ages in evergreen understory shrub Daphniphyllum humile [J]. Trees-Struct Funct, 2007, 21(6): 619 − 629. [12] OSADA N, ONODA Y, HIKOSAKA K. Effects of atmospheric CO2 concentration, irradiance, and soil nitrogen availability on leaf photosynthetic traits of Polygonum sachalinense around natural CO2 springs in northern Japan [J]. Oecologia, 2010, 164(1): 41 − 52. [13] 何祯, 王宗星, 张骏, 等. 浙江省香榧产业发展现状与对策[J]. 浙江农业科学, 2020, 61(7): 1345 − 1347. HE Zhen, WANG Zongxing, ZHANG Jun, et al. Present situation and countermeasures of Torreya grandis ‘ Merrillii’ industry development in Zhejiang [J]. J Zhejiang Agric Sci, 2020, 61(7): 1345 − 1347. [14] HYINK D M, ZEDAKER S M. Stand dynamics and evolution of forest decline [J]. Tree Physiol, 1987, 3(1): 17 − 27. [15] GERISH G. Relating carbon allocation patterns to tree senescence in Metrosideros forests [J]. Ecology, 1990, 71(3): 1176 − 1184. [16] WOLKERSTORFER S V, WONISCH A, STANKOVA T, et al. Seasonal variations of gas exchange, photosynthetic pigments, and antioxidants in Turkey oak (Quercus cerris L.) and Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto Ten.) of different ages [J]. Trees, 2011, 25: 1043 − 1052. [17] 徐超, 王鸿飞, 邵兴锋, 等. 香榧子油抗氧化活性及降血脂功能研究[J]. 中国粮油学报, 2012, 27(8): 43 − 47. XU Chao, WANG Hongfei, SHAO Xingfeng, et al. Study on antioxidant activity and reducing blood fat function of kaga oil [J]. J Chin Cereals Oil Assoc, 2012, 27(8): 43 − 47. [18] SHEN Chaohua, HU Yuanyuan, DU Xuhua, et al. Salicylic acid induces physiological and biochemical changes in Torreya grandis cv. ‘Merrillii’ seedlings under drought stress [J]. Trees-Struct Funct, 2014, 28(4): 961 − 970. [19] LI Tingting, HU Yuanyuan, DU Xuhua, et al. Salicylic acid alleviates the adverse effects of salt Stress in Torreya grandis cv. Merrillii seedlings by activating photosynthesis and enhancing antioxidant systems[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10): e0109492[2021-03-04]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109492. [20] 黄增冠, 喻卫武, 罗宏海, 等. 香榧不同叶龄叶片光合能力与氮含量及其分配关系的比较[J]. 林业科学, 2015, 51(2): 44 − 51. HUANG Zengguan, YU Weiwu, LUO Honghai, et al. Photosynthetic characteristics and their relationships with leaf nitrogen content and nitrogen allocation in leaves at different leaf age [J]. Sci Silv Sin, 2015, 51(2): 44 − 51. [21] 陈佳妮, 廖亮, 黄增冠, 等. 香榧与榧树叶片光合特性及其光保护机制的比较[J]. 林业科学, 2015, 51(10): 134 − 141. CHEN Jiani, LIAO Liang, HUANG Zengguan, et al. A comparative study on photosynthetic characteristics and photoprotective mechanisms between Torreya grandis cv. ‘Merrillii’ and Torreya grandis [J]. Sci Silv Sin, 2015, 51(10): 134 − 141. [22] Von CAEMMERER S, EVANS J R, HUDSON G S, et al. The kinetics of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco [J]. Planta, 1994, 195(1): 88 − 97. [23] 张立波, 娄伟平. 1961—2010年杭州太阳总辐射及日照时数气候变化[J]. 浙江气象, 2013, 34(1): 37 − 41. ZHANG Libo, LOU Weiping. Total solar radiation and sunshine duration’s climate change from 1960−2010 [J]. J Zhejiang Meterol, 2013, 34(1): 37 − 41. [24] YASUMURA Y, HIKOSKA K, HISROSE T. Seasonal changes in photosynthesis, nitrogen content and nitrogen partitioning in Lindera umbellate leaves grown in high or low irradiance [J]. Tree Physiol, 2006, 26(10): 1315 − 1323. [25] MAE T. Leaf senescence and nitrogen metabolism[M]// NOODÉN L D. Plant Cell Death Processes. Amesterdam: Elsevier, 2004: 157 − 168. [26] 赵雨馨. 氮沉降与生物炭对香榧生长和种子品质的影响[D]. 杭州: 浙江农林大学, 2018. ZHAO Yuxin. Effects of Nitrogen Deposition and Biochar on the Growth and Seed Quality of Torreya grandis[D]. Hanghou: Zhejiang A&F University, 2018. [27] BENOMAR L, MOUTAOUFIK M T, ELFERJANI R , et al. Thermal acclimation of photosynthetic activity and RuBisCO content in two hybrid poplar clones[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(2): e438069[2021-03-04]. doi: 10.1101/438069. [28] SHAO Yuhang , LI Shiyu , GAO Lijun , et al. Magnesium application promotes Rubisco activation and contributes to high-temperature stress alleviation in wheat during the grain filling[J/OL]. Front Plant Sci, 2021, 12: 675582[2021-03-04]. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.675582. [29] WARREN C R, ADAMS M A. Evergreen trees do not maximize instantaneous photosynthesis [J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2004, 9: 270 − 274. [30] COCKFIELD S D. Relative availability of nitrogen in host plants of invertebrate herbivores: three possible nutritional and physiological definitions [J]. Oecologia, 1988, 77: 91 − 94. [31] YAMAGUCHI D P, NAKAJI T, HIURA T, et al. Effects of seasonal change and experimental warming on the temperature dependence of photosynthesis in the canopy leaves of Quercus serrata [J]. Tree Physiol, 2016, 36(10): 1283 − 1295. [32] VITALI V, BUNTEGEN U, BAUHUS J. Seasonality matters: the effects of past and projected seasonal climate change on the growth of native and exotic conifer species in central Europe [J]. Dendrochronologia, 2018, 48: 1 − 9. [33] HIKOSAKA K, HIROSE T. Leaf and canopy photosynthesis of C3 plants at elevated CO2 in relation to optimal partitioning of nitrogen among photosynthetic components: theoretical prediction [J]. Ecol Modelling, 1998, 106: 247 − 259. [34] HIKOSAKA K. Nitrogen partitioning in the photosynthetic apparatus of Plantago asiatica leaves grown under different temperature and light conditions: similarities and differences between temperature and light acclimation [J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2005, 46(8): 1283 − 1290. [35] YAMORI W, NOGUCHI K, TERASHIMA I. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis in spinach leaves: analyses of photosynthetic components and temperature dependencies of photosynthetic partial reactions [J]. Plant Cell Environ, 2005, 28(4): 536 − 547. [36] KIRSCHBAUM M U F, FARQUHAR G D. Temperature dependence of whole-leaf photosynthesis in Eucalyptus pauciflora Sieb. ex Spreng [J]. Aust J Plant Physiol, 1984, 11: 519 − 538. [37] HIKOSAKA K, MURAKAMI A, HIROSE T. Balancing carboxylation and regeneration of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate in leaf photosynthesis: temperature acclimation of an evergreen tree, Quercus myrsinaefolia [J]. Plant Cell Envrion, 1999, 22(7): 841 − 849. [38] HIKOSAKA K. Modelling optimal temperature acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus in C3 plants with respect to nitrogen use [J]. Ann Bot, 1997, 80: 721 − 730. [39] MEDLYN B E. The optimal allocation of nitrogen within the C3 photosynthetic system at elevated CO2 [J]. Aust J Plant Physiol, 1996, 23(5): 593 − 603. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20210394

下载:

下载: