-

屋顶绿化是一种独立于自然土壤,在各类建筑的顶部种植树木花卉的绿化形式[1-2],对解决中国城市绿化覆盖率低、绿化资源紧张、“热岛效应”加剧等问题具有重大意义[3-4]。由于屋顶环境的风力大、光照强、湿度低且荷载非常有限[5-6],同时植物的健康生长需要适宜的温度、水分和养分,因此绿化基质应兼备质地轻、持水保水性强、通气透水性强、肥力适中、结构稳定、经济环保等特点[7]。屋顶绿化常用的基质有改良土和无机复合种植土,前者是将田园土与有机物质和无机物质按一定比例混合而成[8],后者是非金属矿物经高温膨化后加入外源添加剂配制而成[9]。相比改良土,无机复合种植土不但能更好地解决基质容重大、透气保水性差、肥力低等问题,还可避免基质结构不稳定、有机质含量及排水色度过高等问题,是屋顶绿化基质的最佳选择[10]。研究表明:以适宜的粒径比配制的珍珠岩轻型基质可改善基质的容重、孔隙度、电导率等指标,既能减轻屋顶负荷,又能避免板结[11]。由于珍珠岩交换吸附能力弱,通过孔隙截留作用和土粒吸附作用的保水保肥效果不理想。因此,在珍珠岩基质中添加合适的改良剂,提高轻型基质的保水保肥性能,对无机复合种植土的研发具有重要意义。保水剂是一种高分子亲水聚合物,可反复吸水,能使基质的容重降低,持水量升高,孔隙状况得到改善[12],水分蒸发及养分流失减缓[13-14]。生物表面活性剂是无毒、可降解的微生物代谢产物,能降低固体物料的表面张力,在农业中常作为润湿剂。适量添加生物表面活性剂不但能使基质有效水分分布更均匀,缓解基质局部干燥,提高水分利用率[15-16],还能增加基质的保水保肥能力,促进植物根系发育[17],降低土壤侵蚀,减少露霜危害和抑制土传病原菌的繁殖[18]。保水剂和生物表面活性剂的应用主要集中在园艺栽培基质、农田土壤和森林土壤,但大多为单施,对两者混施于屋顶绿化专用基质的研究鲜有报道。本研究在施用缓释肥条件下在珍珠岩基质中添加保水剂和生物表面活性剂,结合基质的理化性质和植物生长指标,选出最优屋顶绿化专用基质配方。研究结果可为保水剂和生物表面活性剂在屋顶绿化基质方面的应用提供依据,同时对屋顶绿化新型基质的研发提供思路。

HTML

-

试验地点位于北京林业大学三顷园苗圃(40°01′N,116°35′E),为暖温带半湿润半干旱季风气候区,年均降水量626 mm,其中80%集中在夏季,年均太阳辐射量4.7~5.7 GJ·m−2。

供试材料包括珍珠岩、缓释肥、保水剂和生物表面活性剂。珍珠岩产自河南信阳。将粒径为0.20~1.00 mm和1.00~3.35 mm的2种珍珠岩按照质量比7∶3均匀混合,备用。保水剂为粉末状,粒径180~230 μm,购自烟台润星环保科技有限公司;生物表面活性剂购自西安瑞捷生物科技有限公司。将生物表面活性剂原液用去离子水稀释50倍得到质量分数为2%的生物表面活性剂溶液备用。缓释肥为美国施可得公司(The Scotts Company)的奥绿肥,主要养分组成:氮为15%、五氧化二磷为9%、氧化钾为11%、氧化镁为2%(均为质量分数)。

供试植物金叶莸Caryopteris clandonensis ‘Worcester Gold’和马蔺Iris lactea。试验中选用长势相同,苗龄1 a的植株。

-

试验于2019年3月至2020年7月进行,由基质筛选试验(2019年3−5月)和室外栽培试验(2019年7月至2020年7月)2个部分组成。

-

采用3×3完全随机试验,因素A为保水剂添加量,施用水平(以珍珠岩质量分数计)为0、0.5、1.0 g·kg−1,分别记为A0、A0.5、A1.0;因素B为质量分数2%的生物表面活性剂添加量,施用水平为0、100、200 mL·kg−1,分别记为B0、B100、B200;A0B0为对照组,共9个处理。每个处理重复5次,合计45盆。各处理基质组成见表1。

处理 保水剂/

(g·kg−1)2%生物表面活性剂/

(mL·kg−1)缓释肥/

(g·kg−1)对照 0 0 30 A0B100 0 100 30 A0B200 0 200 30 A0.5B0 0.5 0 30 A0.5B100 0.5 100 30 A0.5B200 0.5 200 30 A1.0B0 1.0 0 30 A1.0B100 1.0 100 30 A1.0B200 1.0 200 30 Table 1. Composition of substrate treatments

等量称取9份1.1节中的珍珠岩,分别平铺于园艺地垫上,按照表1的施用水平向珍珠岩均匀施加2%生物表面活性剂,混匀并风干。再施加保水剂和缓释肥,充分混匀后将各处理装入花盆(高17.5 cm,口径16.0 cm,底径12.5 cm)中,基质厚度设置为15 cm,每组处理装5盆。定期浇水,保持基质湿度为田间持水量的60%左右,将基质在室外培育2个月后(2019年5月)现场取样。

-

根据1.2.1节试验结果,筛选出A1.0B100、A1.0B200等2种基质与对照进行屋顶栽培试验,每种基质种植金叶莸和马蔺各1槽(种植槽长156 cm、宽78 cm、高48 cm,槽底装有排蓄水板和排水口)。按照简单式屋顶花园种植规划,设置厚度为40 cm的基质层。种植前1 d均匀浇水至排水口刚好流出水,种植当天将每株金叶莸和马蔺修剪株高至10 cm,每槽种植32株,株间距17 cm×16 cm。期间由专人管护,定期浇水、除草,栽培1 a后(2020年7月)取样。

-

基质样品采集与处理:称量体积为V的环刀质量(M0)。用环刀取样后,将花盆中剩余基质置于牛皮纸上充分混匀,四分法缩分后将样品封存于聚乙烯自封袋,带回晾土室自然风干,去除杂质、粉碎并过筛。用于全氮测定的样品过100目筛,测定其他指标的样品过10目筛。

将取样后的环刀放入水(密度为ρ水)中并保持水面与环刀上口持平但不淹没环刀顶端,浸泡24 h后称量(M1),将环刀底盖向下置于石英砂上,静置2 h时称量(M2),继续静置至8 h时称量(M3),最终在105 ℃下烘干至恒量,冷却至室温后称量(M4)。测定:基质容重A=(M4−M0) /V;基质饱和含水量B=(M1−M4)/(M4−M0);基质毛管持水量C=(M2−M4)/(M4−M0);基质田间持水量D=(M3−M4)/(M4−M0);总孔隙度E=AB/ρ水;毛管孔隙度F=CA/ρ水;通气孔隙度G=E−F;水气比H=F/G[19]。

pH、电导率测定:以质量比为5∶1的水土比将去离子水和基质混合震荡30 min,静置后用雷磁S-3C型pH计测定pH,MP521型电导率仪测定电导率。

全氮、有效磷、速效钾和阳离子交换量测定参考《土壤农化分析》[20]。全氮:凯氏定氮法;有效磷:0.5 mol·L−1 碳酸氢钠浸提-钼锑抗比色法(波长700 nm);速效钾:醋酸铵浸提-火焰光度计法;阳离子交换量:氯化钡-硫酸镁(强迫交换)法。

-

将基质的理化指标组成优劣排序值矩阵,对基质进行综合评价,评分越高表明基质越优[21]。

-

每槽随机选取5株植物,测定株高、根长、地上部鲜质量和根部鲜质量以及植物总鲜质量,并计算根冠比。

-

根据f(x)=(x−xmin)/(xmax−xmin)求得植物某一形态指标的隶属函数值[22]。其中:x为该指标某一测定值,xmax和xmin分别表示该指标的最大值和最小值。基质综合评价指数为各形态指标隶属函数值的平均数,其值越大表明栽培基质越优。

-

数据的整理和制图用Excel 2016,数据分析用SPSS 20.0。

1.1. 供试材料

1.2. 试验设计

1.2.1. 基质筛选试验

1.2.2. 种植试验

1.3. 测定项目及方法

1.3.1. 基质理化性质测定

1.3.2. 基质理化性质综合评价

1.3.3. 植株指标测定

1.3.4. 植株指标综合评价

1.4. 数据分析

-

由表2可知:随保水剂和生物表面活性剂施用量增加,基质的容重、总孔隙度和通气孔隙度均呈降低趋势;毛管孔隙度和水气比呈升高趋势。就容重和通气孔隙度而言,8个处理组较对照均显著(P<0.05)降低,且在A1.0B200处理下达到最小值0.096 g·cm−3和17.11%。就总孔隙度而言,除A0.5B200处理较对照显著(P<0.05)降低11.12%外,其余各处理较对照均无显著差异。毛管孔隙度在A1.0B0处理下达到最大值54.19%,较对照提高10.82%,但各处理间差异均不显著。各处理水气比为1.76~3.14,其中A1.0B200处理显著(P<0.05)高于除A1.0B100外的其他处理。

处理 容重/(g·cm−3) 总孔隙度/% 通气孔隙度/% 毛管孔隙度/% 水气比 对照 0.134 a 76.98 a 28.08 a 48.90 a 1.76 e A0B100 0.122 b 72.43 ab 24.04 b 48.39 a 2.02 de A0B200 0.115 c 76.03 ab 22.94 bc 53.09 a 2.33 cd A0.5B0 0.119 b 73.28 ab 22.64 bcd 50.64 a 2.26 cd A0.5B100 0.113 bc 71.49 ab 20.53 cde 50.97 a 2.50 cd A0.5B200 0.099 d 68.42 b 19.94 de 48.48 a 2.43 cd A1.0B0 0.112 bc 75.20 ab 21.01 cd 54.19 a 2.60 bc A1.0B100 0.104 cd 71.80 ab 18.07 ef 53.73 a 2.99 ab A1.0B200 0.096 d 70.65 ab 17.11 f 53.54 a 3.14 a 说明:同列不同小写字母表示不同处理间差异显著(P<0.05) Table 2. Physical properties of substrate treatments

-

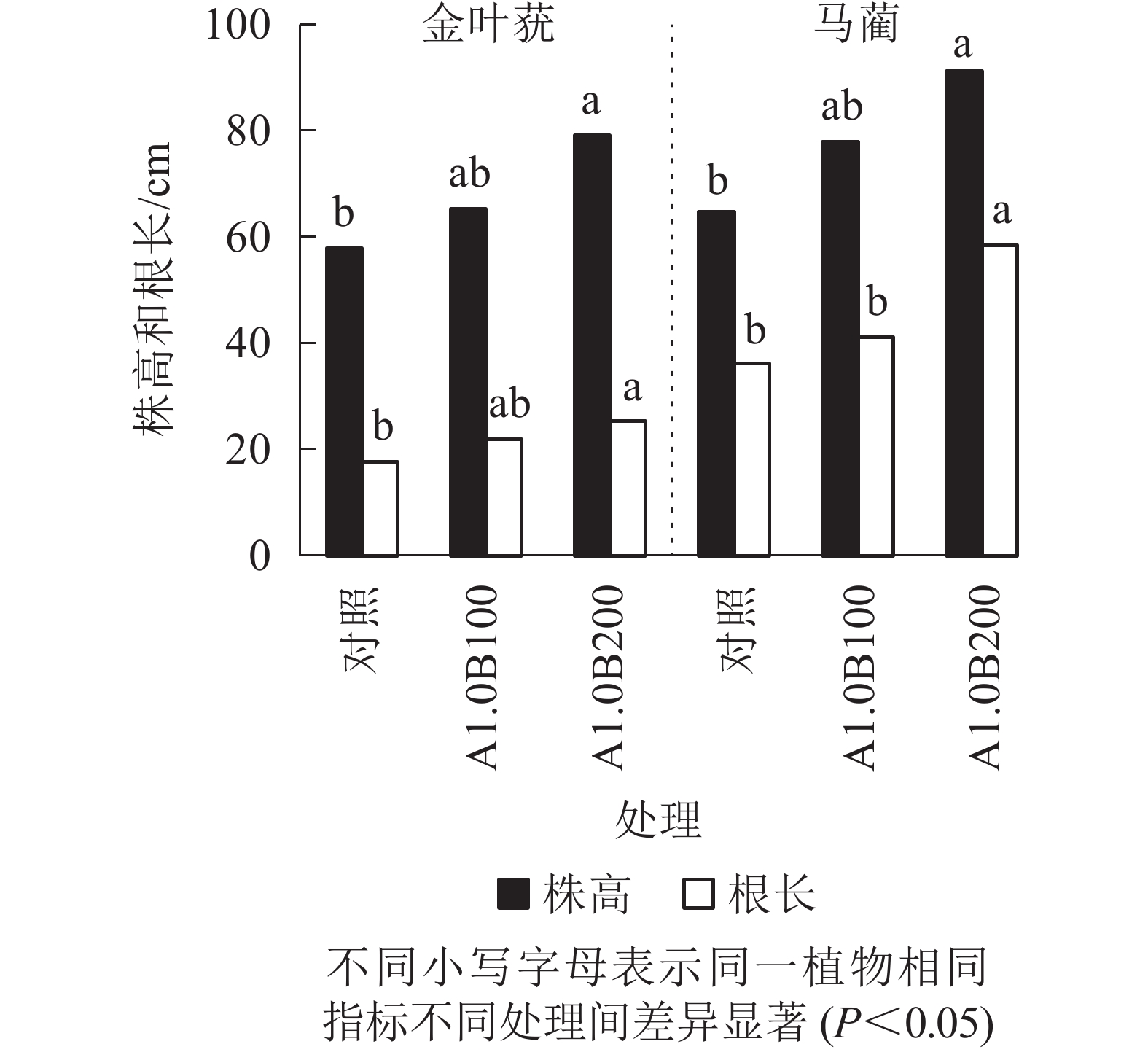

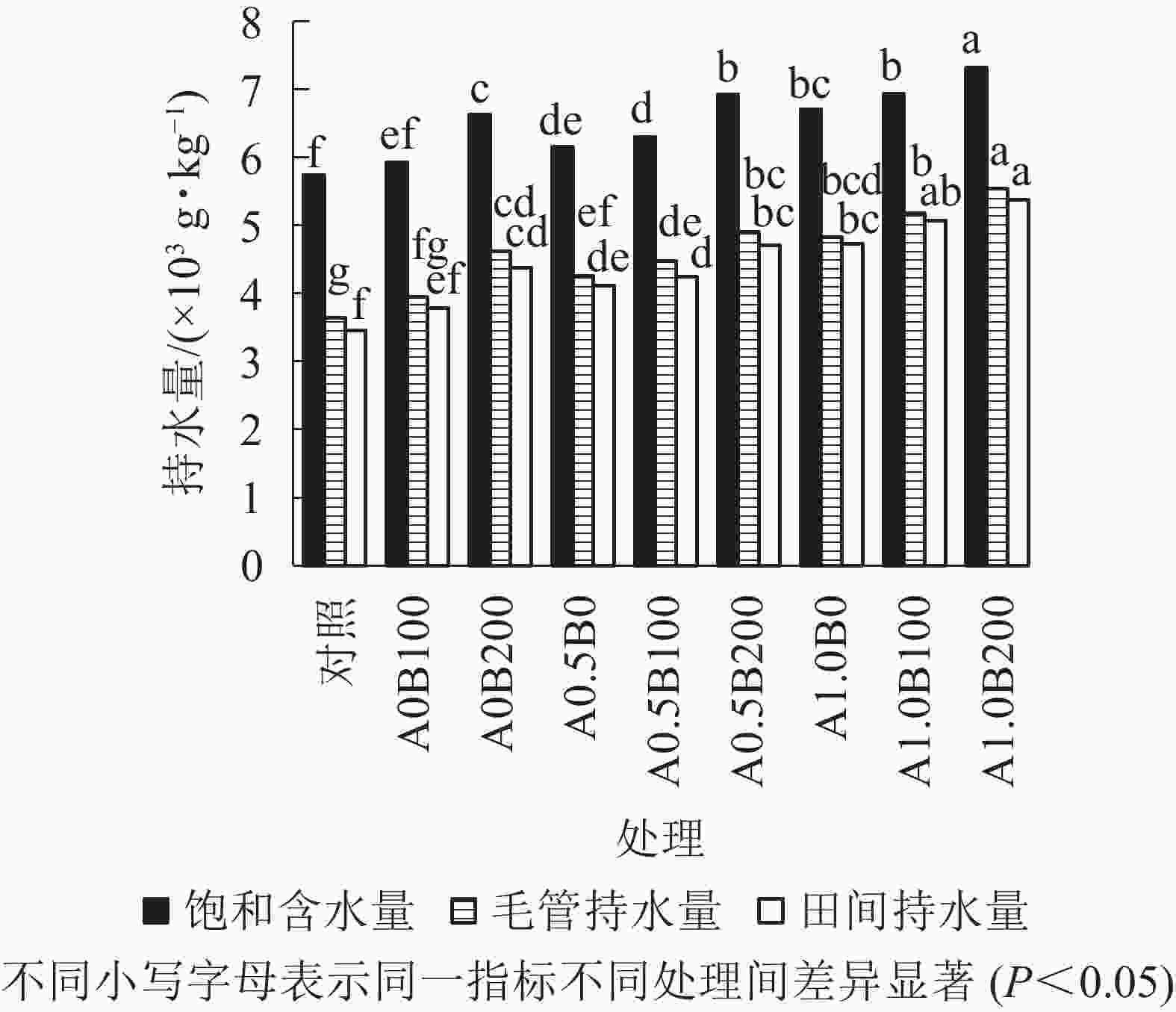

由图1可知:随保水剂和生物表面活性剂施用量增加,基质饱和含水量、毛管持水量、田间持水量均呈升高趋势,且均在A1.0B200处理下达到最大值,分别较对照显著(P<0.05)提高27.48%、52.20%和55.55%。单施保水剂或生物表面活性剂均提高了基质的持水量,其中A1.0B0处理的饱和含水量、毛管持水量、田间持水量较对照分别显著(P<0.05)提升16.88%、32.70%和36.71%;A0B200处理较对照分别提升15.48%、27.04%和26.60%。混施保水剂和生物表面活性剂与单施保水剂或生物表面活性剂相比,对基质持水量的提高更显著(P<0.05),其中A1.0B200处理的饱和含水量、毛管持水量和田间持水量较A1.0B0处理分别提高9.07%、14.70%和13.78%,较A0B200处理分别提高10.39%、19.81%和22.86%。

-

如表3所示:单施生物表面活性剂可降低基质pH,A0B100和A0B200处理的pH较对照均显著(P<0.05)降低。其中,A0B100处理的pH为各处理间最低,较对照显著降低(P<0.05),较A0B200处理无显著差异。随单施保水剂用量增加,基质pH先降低后升高。混施保水剂和生物表面活性剂降低了基质的pH,A1.0B200处理下,pH比对照显著(P<0.05)降低,基质更接近中性。

处理 pH 电导率/

(μS·cm−1)阳离子交换量/

(cmol·kg−1)全氮/

(g·kg−1)有效磷/

(mg·kg−1)速效钾/

(mg·kg−1)对照 8.22 a 343.44 cd 5.74 f 5.75 e 96.70 e 2 703.3 e A0B100 6.51 d 270.36 d 5.93 ef 5.89 e 101.80 e 2 883.4 d A0B200 6.86 bcd 341.76 cd 6.63 c 5.83 e 107.30 de 2 957.8 cd A0.5B0 7.38 b 553.74 b 6.16 de 6.09 d 118.40 cd 2 937.5 cd A0.5B100 7.01 bcd 438.95 bc 6.30 d 6.37 bc 125.50 bc 3 088.1 bc A0.5B200 6.68 cd 480.10 bc 6.93 b 6.44 ab 129.80 abc 3 143.8 b A1.0B0 8.01 a 768.74 a 6.71 bc 6.24 cd 131.30 abc 3 178.4 b A1.0B100 7.12 bc 580.76 b 6.94 b 6.43 ab 145.64 a 3 421.8 a A1.0B200 7.32 b 564.96 b 7.32 a 6.60 a 139.60 ab 3 386.6 a 说明:同列不同小写字母表示不同处理间差异显著(P<0.05) Table 3. Chemical properties of substrate treatments

-

相同生物表面活性剂施用水平下,随保水剂施用量增加,基质电导率呈升高趋势(表3),并在A1.0B0处理下达到最大值,较其余处理显著(P<0.05)提高。相同保水剂施用水平下,生物表面活性剂施用量为100或200 mg·kg−1时,基质电导率较不施生物表面活性剂时均显著(P<0.05)降低,但在2种施用量之间,生物表面活性剂对电导率的降低效果无显著差异。

-

随着保水剂和生物表面活性剂用量增加,各处理阳离子交换量以及全氮、有效磷和速效钾质量分数均呈升高趋势(表3)。其中阳离子交换量和全氮质量分数在A1.0B200处理下达到最大值,较对照显著(P<0.05)增加,A1.0B10处理下次之。A1.0B100处理下的有效磷和速效钾质量分数最高,分别较对照显著(P<0.05)提高44.36%和26.58%,A1.0B200处理次之,较A1.0B100无显著差异。单施保水剂可显著(P<0.05)提高基质的阳离子交换量以及全氮、有效磷和速效钾质量分数;A1.0B0处理基质的阳离子交换量以及全氮、有效磷和速效钾质量分数较对照均显著(P<0.05)增加。单施生物表面活性剂时,仅基质的阳离子交换量和速效钾质量分数显著(P<0.05)提高。

-

采用矩阵法综合评价各组基质,容重越小得分越高;总孔隙度>70%时,越大得分越高;水气比越接近3.00评分越高;通气孔隙度和持水孔隙度、饱和含水量、毛管持水量、田间持水量、阳离子交换量以及全氮、有效磷和速效钾质量分数越大评分越高;pH和电导率分别以接近7.00和500 μS·cm−1为优。最终求得各处理得分:对照为35分、A0B100为38分、A0B200为67分、A0.5B0为58分、A0.5B100为71分、A0.5B200为80、A1.0B0为87分、A1.0B100为100分和A1.0B200为100分,综合评分最高的2组基质为A1.0B100和A1.0B200,故选用此2种基质进行栽培试验。

-

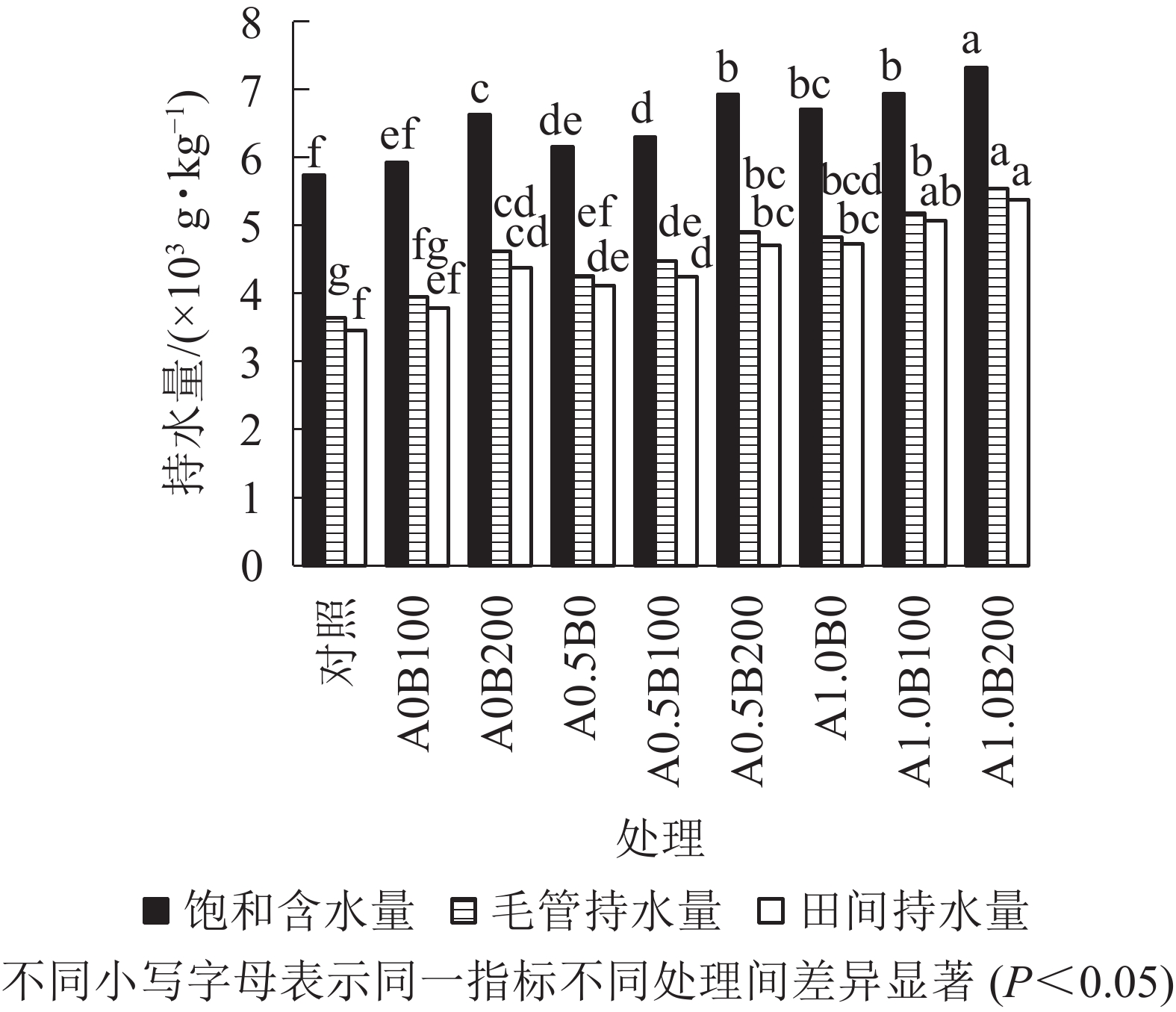

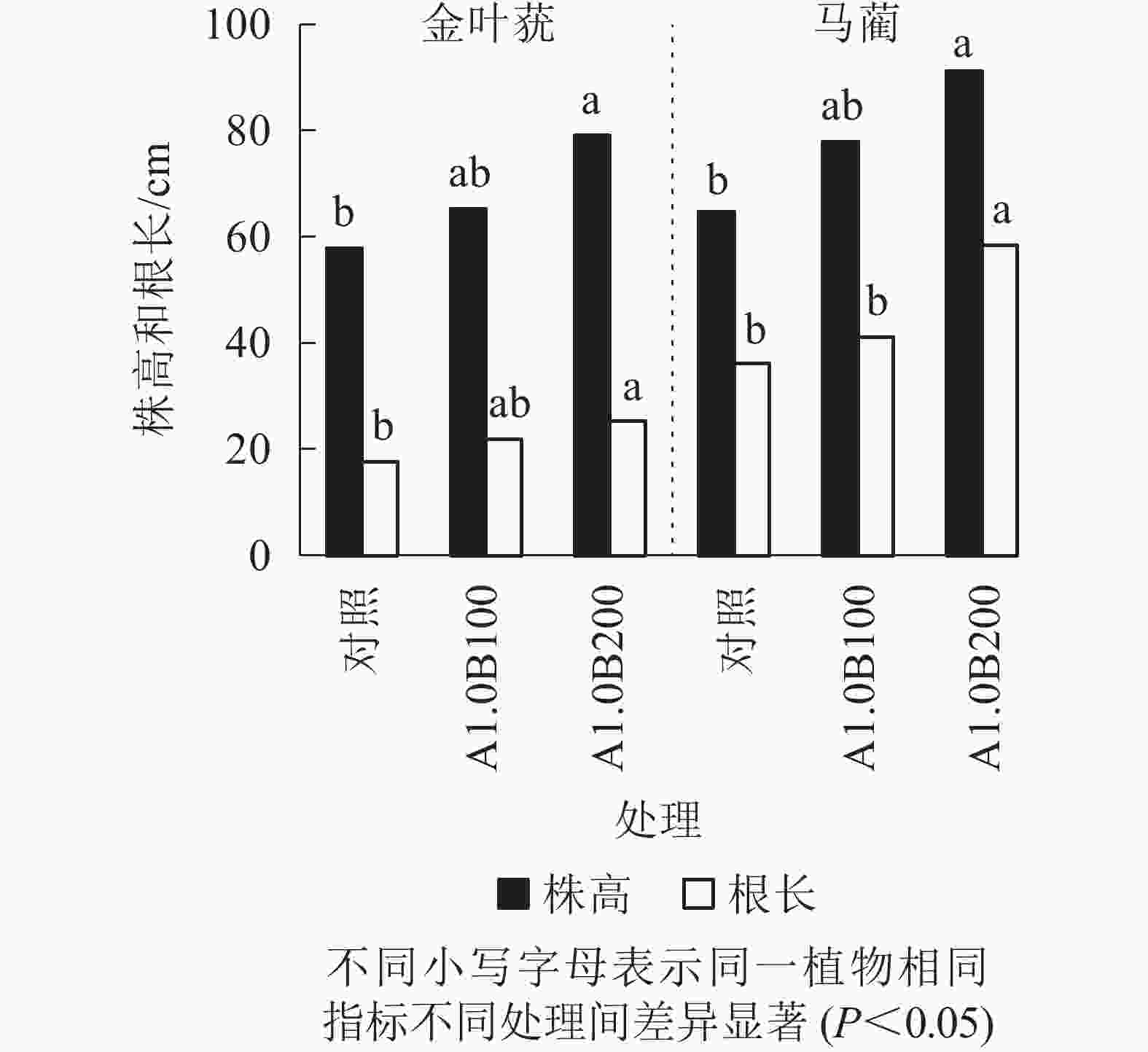

如图2所示:无论是金叶莸还是马蔺,2种植物的株高和根长均为A1.0B200处理最大,A1.0B100处理次之、对照最小。在A1.0B200基质上栽培金叶莸和马蔺较在对照基质上均显著(P<0.05)提高了株高和根长,而在A1.0B100基质上的栽培效果与在对照上相比,金叶莸的株高、根长增高均不显著。

由表4可知:2种植物的总鲜质量、地上部鲜质量和根部鲜质量均为A1.0B200处理最大,A1.0B100处理次之,对照最小。在A1.0B200栽培基质上,金叶莸的总鲜质量、地上部鲜质量和根部鲜质量均达到最大值,较对照均有显著(P<0.05)提高,较A1.0B100均无显著差异;马蔺的总鲜质量显著(P<0.05)大于对照和A1.0B100处理,地上部和根部鲜质量均显著(P<0.05)大于对照处理,较A1.0B100无显著差异。金叶莸和马蔺的根冠比在各处理间差异不显著。

植物 处理 总鲜质量/g 根鲜质量/g 地上部鲜质量/g 根冠比 金叶莸 对照 49.74 b 14.03 b 35.71 b 0.39 a A1.0B100 61.09 ab 18.26 ab 42.83 ab 0.43 a A1.0B200 72.59 a 22.95 a 49.64 a 0.48 a 马蔺 对照 85.56 b 36.19 b 49.37 b 0.73 a A1.0B100 104.00 b 44.08 ab 59.92 ab 0.76 a A1.0B200 129.16 a 51.69 a 77.47 a 0.68 a 说明:同一植物相同指标不同小写字母表示不同处理间差异显著(P<0.05) Table 4. Fresh weight and root top ratio of plant

-

通过植株生长指标的隶属度函数,计算得出A1.0B200基质的综合评价系数大于A1.0B100处理和对照,即A1.0B200处理为本研究最适宜屋顶绿化基质配方(表5)。

处理 金叶莸 马蔺 综合评价

系数综合

排名株高 根长 总鲜

质量根鲜

质量地上部

鲜质量根冠比 株高 根长 总鲜

质量根鲜

质量地上部

鲜质量根冠比 对照 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.67 0.06 3 A1.0B100 0.35 0.56 0.50 0.47 0.51 0.42 0.50 0.23 0.42 0.51 0.38 1.00 0.49 2 A1.0B200 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.00 0.92 1 Table 5. Comprehensive evaluation of growth indexes of C.clandonensis ‘Worcester Gold’ and I. lactea

2.1. 基质物理性质

2.1.1. 容重、孔隙度及水气比

2.1.2. 持水量

2.2. 基质化学性质

2.2.1. pH

2.2.2. 电导率

2.2.3. 阳离子交换量和基质养分

2.3. 基质理化性质综合评价

2.4. 植物生长指标

2.5. 植物生长指标综合评价

-

降低基质容重可减轻屋顶系统的载质量,从而为适当增加基质厚度,种植较大型植物提供条件。本研究各处理基质容重均接近0.1 g·cm−3,达到基质容重的标准值(0.1~0.5 g·cm−3)[23]。施用保水剂和生物表面活性剂均降低了珍珠岩基质的容重、总孔隙度和通气孔隙度,提高了其毛管孔隙度,原因可能是保水剂在基质中吸水膨胀,使单位体积内土粒减少[24],堵塞了部分孔隙[25],并将部分通气孔隙转变为毛管孔隙。这与崔敏[15]的研究结果基本一致。孔隙状况影响基质的通气性状,栽培基质的总孔隙度应控制在54%~96%,水气比以2~4较为合理[26]。除A0.5B200处理外,其余8组基质的总孔隙度均能达到常用无机复合种植土70%的标准[2],而一般的改良土仅达49%。施加保水剂和生物表面活性剂还可改善珍珠岩基质的水气比,A1.0B100和A1.0B200基质的水气比最优,均较为接近3.0。混施保水剂和生物表面活性剂不但可以改善基质的三相比例、持水性能,还能提高其水肥利用率[27-28]。本研究中A1.0B200处理的饱和含水量、毛管持水量和田间持水量均大于其余处理,可能与施加生物表面活性剂可显著增加土壤水分分布的均匀性,进而改善持水性能有关[16]。

密集型屋顶绿化栽培基质的pH适宜范围为5.5~8.0,偏中性的基质更能保证基质养分的有效性。除对照和A1.0B0这2组基质外,其余6组基质pH均在适宜范围内。ABAD等[29]认为:栽培基质的电导率应≤500 μS·cm−1。本研究中各处理的电导率为270~770 μS·cm−1,基本符合要求,但也有研究指出电导率在100~2 000 μS·cm−1也是合理的[30]。

施加保水剂和生物表面活性剂均提高了基质的阳离子交换量,增强了珍珠岩基质的保肥能力。施加聚丙烯酸保水剂可以增加土壤的阳离子交换量,且在施用量为0.25%时达到最佳保肥效果[31]。生物表面活性剂呈酸性,同时具有一定的还原性,施加生物表面活性剂使珍珠岩中交换性阳离子Al3+和Fe2+的有效性增加,同时将部分Fe3+还原,这可能是生物表面活性剂提高珍珠岩基质阳离子交换量的主要原因[32]。本研究中,施加保水剂和生物表面活性剂提高了施肥条件下珍珠岩基质的全氮、有效磷和速效钾质量分数,表明保水剂和生物表面活性剂可减少珍珠岩基质的养分淋失。马焕成等[14]研究表明:保水剂对土壤中的氮、磷、钾有较强的吸附作用,在改善土壤水分状况的同时,可降低土壤养分淋失,改善土壤养分状况。CHANG等[33]研究表明:施肥条件下施加生物表面活性剂通过改善草坪土壤水分状况,从而减少草坪土壤养分流失。保水剂可与一些活性基团和离子发生反应,吸附养分[34];生物表面活性剂可使土壤水分分布更均匀[16],因此本研究与马焕成等[14]和CHANG等[33]的研究结果基本一致。

植物对基质的适应性可通过植物生长指标反映,植株长势越好表明基质越优。大量研究证实:施用保水剂或生物表面活性剂可明显促进植物的生长。卫星等[35]研究指出:保水剂提高了基质对氮、磷、钾的吸附和固定作用,增强了基质的保水能力,使白桦Betula platyphylla苗高和地径提高;MA等[36]研究表明:保水剂施用量为1%时对土壤结构改善效果最好,促进了结缕草Zoysia japonica的生长;CHOI等[37]研究发现:施加生物表面活性剂的基质上,鸡冠花Celosia cristata的株高、冠幅、鲜质量和干质量比不施加的处理提高明显。本研究中A1.0B100和A1.0B200处理组的金叶莸和马蔺的株高、根长和根冠比等指标均高于对照,主要是因为施加保水剂和生物表面活性剂明显改善了基质的水气比、阳离子交换量和酸碱性等理化性质,使基质更适合于植物的生长。此外,YANG等[38]研究发现:保水剂与氮肥混施增强了冬小麦Triticum aestivum叶绿素含量,进而提高其光合强度和水分利用效率,促进了植物的生长。本研究还发现:与2%生物表面活性剂施加量为100 mL·kg−1时相比,施加量为200 mL·kg−1时仅对马蔺生长的促进作用更明显,这可能与植物种类有关。但保水剂和生物表面活性剂对植物生长发育的促进作用也要建立在严格控制用量的基础上,因为保水剂中含大量的可溶性离子,过量施用会引起植物的盐害,同时栽培基质中生物表面活性剂用量过高会阻碍植物根系生长,抑制种子萌发[15, 39]。

-

施加保水剂和生物表面活性剂可以提高珍珠岩基质的持水和保肥性能,改善水气比,减缓养分淋失,同时降低容重。在1.0 g·kg−1保水剂和200 mL·kg−1 质量分数2%生物表面活性剂的施加量下,A1.0B200珍珠岩基质的持水性能最佳,水气比接近3.00,全氮、速效磷、有效钾质量分数达到最高,pH为偏中性,保肥效果最好。结合金叶莸和马蔺生长指标的综合评价,A1.0B200被筛选其为最优基质。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: