-

目前,二氧化碳(CO2)升高导致的全球变暖已成为人类生存所面临的重要生态问题,土壤呼吸作为大气最大的CO2排放源之一,已成为科学界研究的热点。土壤呼吸在陆地生态系统碳循环和碳收支中占有重要地位[1],其任何微小变化都将影响大气CO2的排放[2]。土壤作为森林生态系统中的最大碳库[3],其呼吸作用占森林生态系统碳排放的30%~80%[4],是森林参与全球碳循环的关键部分。因此,探究森林生态系统土壤呼吸动态变化特征对评估陆地生态系统碳循环具有重要意义。林下植被通过影响森林生态系统的地上及地下过程,在驱动森林生态系统的结构和功能方面发挥了重要作用[5−6]。研究表明:桉树Eucalyptus人工林林下植被根系呼吸占土壤总呼吸的11%~36%[7],对土壤总呼吸具有重要贡献。林下植被去除是人工林经营中一种常见的管理措施。一般而言,去除林下植被可以减少林冠与林下物种的竞争,促进种苗萌芽和生长[8−9],改变林地土壤微环境及养分有效性[10−11]。林地土壤环境的改变会引起土壤呼吸速率不同程度的升高或降低,进而影响森林生态系统土壤碳循环[12−15]。

桉树是中国南方速生丰产林的重要造林树种之一。现全球桉树人工林面积2 000多万hm2,占世界人工林面积的15%,截至2015年中国桉树人工林面积超过450万hm2,仅次于印度和巴西[16]。目前,对桉树人工林土壤呼吸的研究多集中在林型、环境因子、氮添加及林下植被去除的响应等方面[17−20],而物理去除和施用除草剂[13, 21−22]引起的土壤呼吸组分动态差异的研究少见报道。本研究以雷州半岛北部10年生尾巨桉Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis人工林为研究对象,分析物理和化学2种方式去除林下植被后林地土壤呼吸组分动态变化及其驱动因素,以期深入了解桉树人工林土壤碳循环过程,为经营干扰下森林土壤碳排放估算提供科学依据。

-

研究区位于广东湛江桉树林生态系统国家定位观测研究站(21°15′53.5″N,110°05′39.2″E,平均海拔为150.4 m)。该区地处北热带湿润大区雷琼区北缘,为海洋性季风气候。年平均气温为23.2 ℃,年平均降水量为1723.1 mm,集中在5—10月(数据来源于遂溪县气象台,为1981—2010年均值)。土壤类型为玄武岩发育的砖红壤,土壤肥力中等,土层厚度达84 cm以上。林下灌木有五色梅Lantana camara、白背叶Mallotus apelta、鹅掌柴Schefflera octophylla、盐肤木Rhus chinensis、三桠苦Evodia lepta、菝葜Smilax china等,灌木层盖度为30%。林下草本有南美蟛蜞菊Wedelia trilobata、白花鬼针草Bidens pilosa var. radiata、牛筋草Eleusine indica、马唐Digitaria sanguinalis、山管兰Dianella ensifolia、芒萁Dicranopteris dichotoma等,草本层盖度为80%。

-

2017年12月,选取10年生尾巨桉人工林,林分密度为667株·hm−2,郁闭度为47%,平均树高为22.66 m,平均胸径为22.70 cm。采用随机区组设计,设置物理、化学2个林下植被去除处理,以未去除为对照。每个处理各布置3块40 m×40 m重复样地,样地间隔10 m,在每个样地中心设置1个20 m × 20 m的样方。物理去除使用割灌机贴地割除灌草并作移除处理,移除前在每个20 m × 20 m样方内随机设置3个2 m × 2 m的灌草收集样方,收集林下植被地上部分,并分别称取鲜质量,测定含水量(将植被新鲜样品放置于烘箱内,在65 ℃条件下烘至恒量),换算为单位面积干质量。化学去除喷施除草剂(草甘膦铵盐水剂,草甘膦铵盐质量分数为33%,草甘膦质量分数为30%,用量为7 500 mL·hm−2),植被残体不移除。3次林下植被去除时间分别为2017年12月、2018年6月、2018年12月,每次在物理去除和对照喷施与化学去除等量的不含除草剂的水,以去除施药导致土壤水分增大带来的差异。3次物理去除处理的灌草地上部分生物量均值分别为5.94、5.70、4.56 t·hm−2。试验地处理前后土壤基本概况见表1。

采样时间(年-月) 处理 有机碳/(g·kg−1) 全氮/(g·kg−1) 全磷/(g·kg−1) pH 2017-12 − 33.37±0.30 a 2.50±0.06 a 0.89±0.01 a 4.48±0.02 a 2019-03 物理 30.03±0.73 b 2.09±0.08 b 0.85±0.01 ab 3.97±0.01 c 化学 32.65±0.52 a 2.54±0.06 a 0.80±0.04 b 4.12±0.01 b 对照 33.76±0.58 a 2.48±0.09 a 0.90±0.02 a 4.40±0.01 a 说明:数值均为0~20 cm土层均值±标准误。不同小写字母表示不同处理间差异显著(P<0.05);−表示林下植被去除处理之前的本底调查 Table 1. Survey of sample plots

-

2018年3月至2019年3月,每月月中和月底测定2次(避开阴雨天气)土壤呼吸速率,测定时间为9:00—12:00。测定采用LI-8100A土壤碳通量自动测量系统(Li-COR),系统配套的土壤温度和湿度传感器测定土壤5 cm深处的温度和湿度(体积含水率)。为降低断根呼吸的影响[23],于测定开始前3个月,在每个20 m × 20 m样方中随机设置9个1 m×1 m小区(相互间隔最小为2 m),作3类观测小区:断根去凋(切断根系+去除凋落物层)、去凋(去除凋落物层)、对照(保留根系和凋落物层)。每类小区重复3次。断根小区采用壕沟法(宽度20 cm,深度100 cm),硬质聚氯乙烯板置于沟中用以阻隔林木根系,并按原土壤层次进行回填。壕沟距离树干2~3 m,故可认为死根分解对土壤呼吸影响较小[24]。去凋小区移除现有凋落物层,上方放置塔形尼龙网筛阻止凋落物进入。每个小样方中心位置埋设1个PVC环(内径20 cm,高10 cm),垂直压入土壤5 cm深处。每次测定前剪除环内活地被物,并保证在整个观测期间对土壤环无扰动。

-

土壤呼吸组分计算公式为:RM=R1;RR=R2−R1;RL=R3−R2;RA=R3。其中:RM为矿质土壤呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);RR为根系呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);RL为凋落物层呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);R1为断根去凋小区土壤呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);R2为去凋小区土壤呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);R3对照小区土壤呼吸速率,即土壤总呼吸速率RA(μmol·m−2·s−1)。

采用指数方程描述土壤呼吸及其组分与土壤温度的关系:

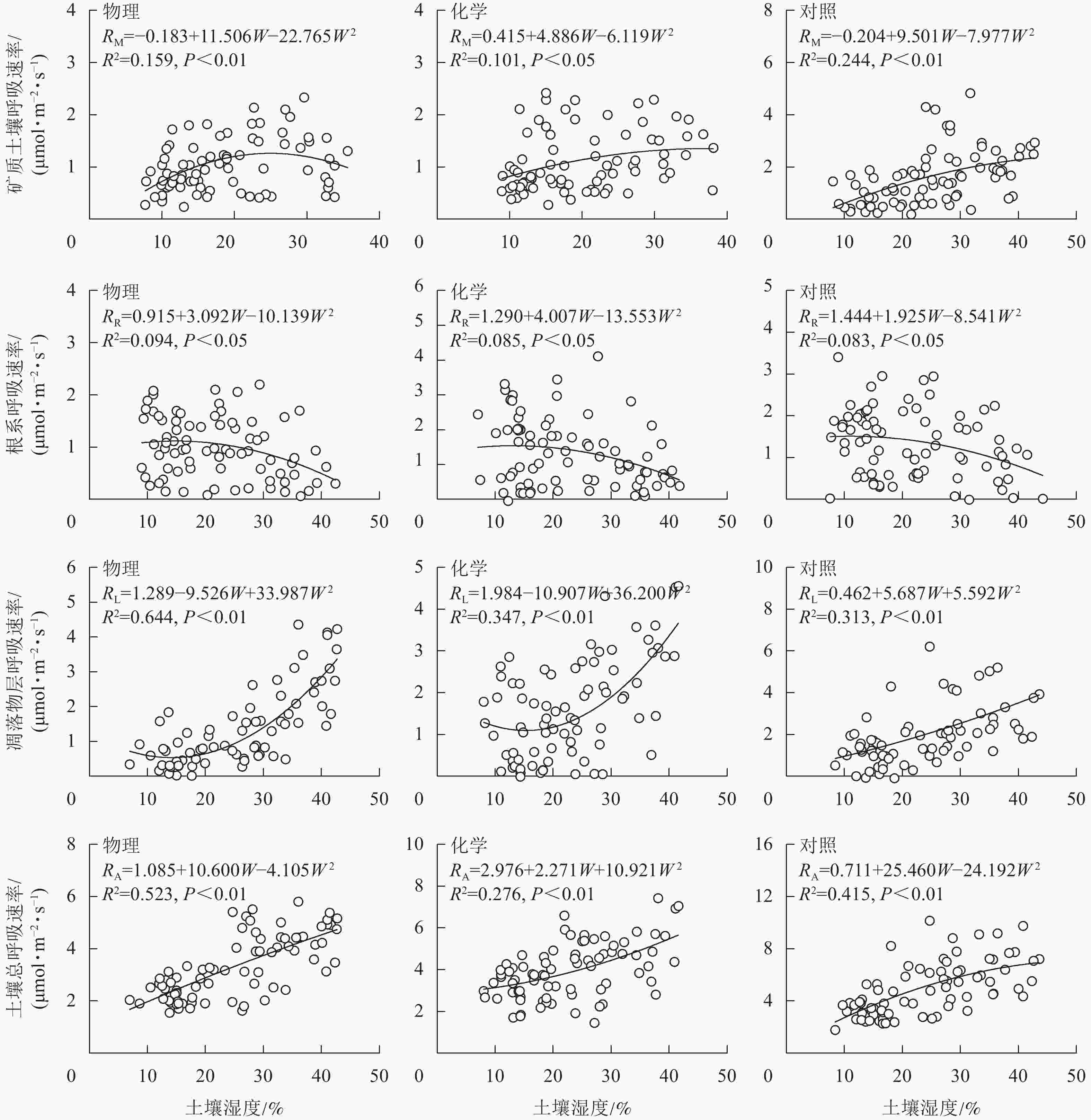

$ R=a{\mathrm{e}}^{bT} $ 。其中:R为土壤总呼吸速率或各组分呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);T为对应处理的土壤温度(℃,5 cm);a为温度0 ℃时的土壤呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);b为温度反应系数。采用二次函数方程描述土壤呼吸及其组分与土壤湿度的关系:

$ R={c}_{1}+{c}_{2}W+{c}_{3}{W}^{2} $ 。其中:R为土壤总呼吸速率或各组分呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);W为土壤湿度(%,5 cm),c1、c2、c3为拟合参数。采用线性模型描述土壤呼吸及其组分土壤温度、湿度的叠加效应:

$ \mathrm{l}\mathrm{n}R=\alpha +\beta T+\gamma W+\delta {T}^{2}+\varepsilon {W}^{2} $ 。其中:R为土壤总呼吸速率或各组分呼吸速率(μmol·m−2·s−1);T为对应处理的土壤温度(℃,5 cm);W为土壤湿度(%,5 cm);α、β、γ、δ、ε为拟合参数。土壤呼吸温度敏感性系数(Q10)计算公式为:

$ {Q}_{10}={\mathrm{e}}^{10b} $ 。其中:b为温度反应系数。采用重复测量方差(ANONA)检验土壤呼吸速率及其组分和土壤温度、湿度变化的差异显著性;单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA)检验土壤呼吸速率及土壤温度、湿度年均值差异性。

-

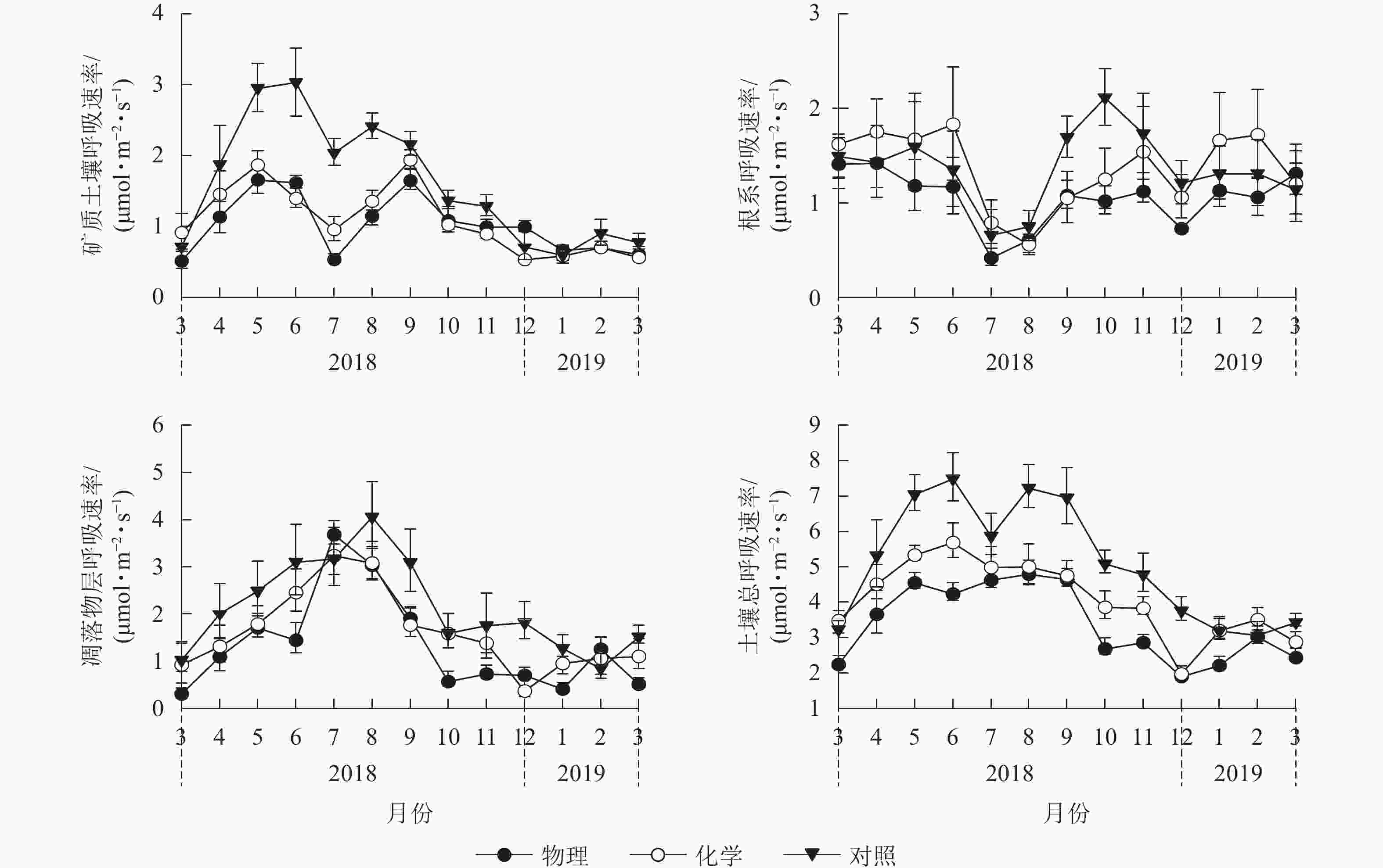

从表2可见:与对照相比,物理和化学去除分别使土壤总呼吸速率降低了33.27%和19.73%,且三者存在显著差异(P<0.05)。物理和化学去除使矿质土壤呼吸速率分别降低了35.40%和31.68%(P<0.05)。仅物理去除使根系呼吸速率降低了25.55%,化学去除对根系呼吸速率无显著影响。物理和化学去除分别使凋落物层呼吸速率降低了36.53%和23.74% (P<0.05)。矿质土壤呼吸速率、根系呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率对土壤总呼吸速率的贡献率分别为26.34%~31.29%、30.10%~35.26%和36.45%~39.40%,凋落物层呼吸速率和根系呼吸速率占主要部分。与对照相比,仅化学去除显著降低了矿质土壤呼吸速率对土壤总呼吸速率的贡献率(26.34%)(P<0.05)。

处理 RA/

(μmol·m−2·s−1)RM RR RL T1/℃ 数值/

(μmol·m−2·s−1)贡献率/% 数值/

(μmol·m−2·s−1)贡献率/% 数值/

(μmol·m−2·s−1)贡献率/% 物理 3.45±0.14 C 1.04±0.06 B 31.29±1.56 A 1.02±0.07 B 32.26±2.28 A 1.39±0.13 B 36.45±2.28 A 24.32±0.36 Aa 化学 4.15±0.15 B 1.11±0.06 B 26.34±1.08 B 1.37±0.11 A 35.26±2.76 A 1.67±0.13 B 38.39±2.57 A 24.94±0.39 Aa 对照 5.17±0.23 A 1.61±0.12 A 30.51±1.65 A 1.37±0.09 A 30.10±2.27 A 2.19±0.17 A 39.40±1.83 A 25.28±0.41 Aa 处理 T2/℃ T3/℃ W1/% W2/% W3/% SOCs1/

(t·hm−2)SOCs2/

(t·hm−2)SOCs3/

(t·hm−2)物理 24.56±0.36 Aa 24.00±0.32 Aa 18.00±0.75 Bc 20.86±0.83 Ab 24.03±0.94 Aa 55.93±1.19 Cb 63.02±0.76 Ba 55.18±0.47 Cb 化学 24.00±0.33 Aa 24.39±0.35 Aa 18.45±0.75 Bb 21.47±0.89 Aa 21.60±0.81 Aa 59.46±0.72 Bb 65.66±0.38 Aa 62.89±1.14 Ba 对照 24.80±0.36 Aa 24.53±0.33 Aa 22.80±0.90 Aa 20.50±0.90 Aa 22.42±0.89 Aa 63.98±0.95 Ab 61.60±0.85 Bb 69.01±0.69 Aa 说明:不同大写字母表示不同林下植被处理方式间差异显著(P<0.05),不同小写字母表示不同试验小区间差异显著(P<0.05)。RA、RM、RR、RL分别为土壤总呼吸速率、矿质土壤呼吸速率、根系呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率。T1、T2、T3分别表示断根去凋小区、去凋小区、对照小区土壤温度。W1、W2、W3分别表示断根去凋小区、去凋小区、对照小区土壤湿度。SOCs1、SOCs2、SOCs3分别表示断根去凋小区、去凋小区、对照小区0~20 cm土壤有机碳储量。数值为平均值±标准误 Table 2. One way ANOVA for the means of soil respiration components, soil temperature, soil moisture, and soil organic carbon storage

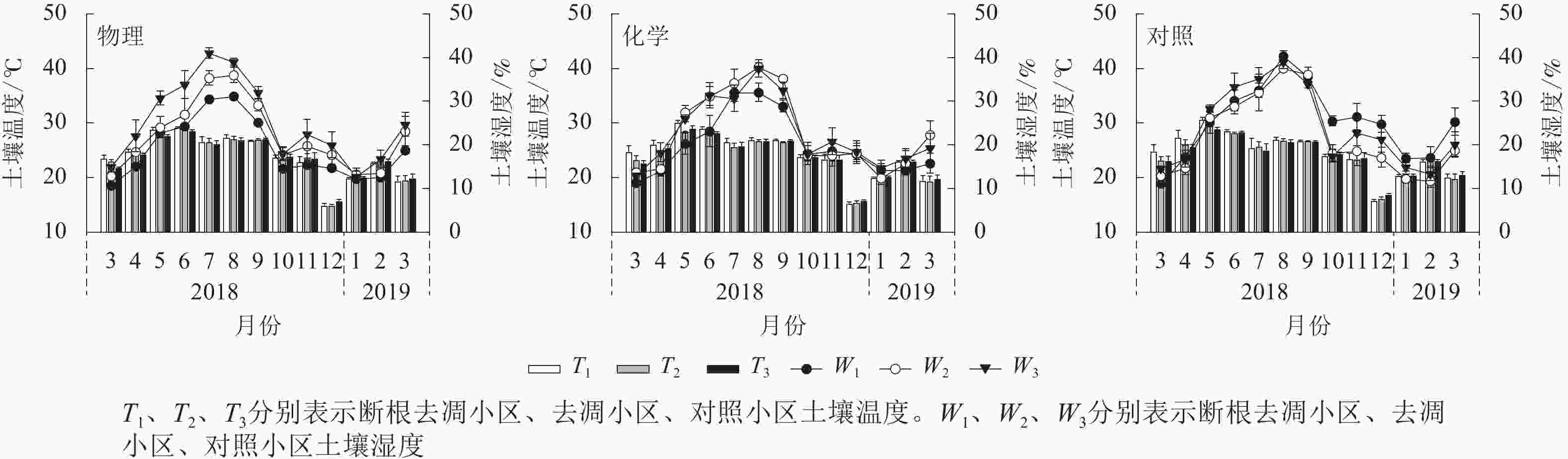

不同处理间土壤温度无显著差异(P>0.05),说明土壤温度对林下植被和凋落物去除未产生明显变异。植被去除显著降低了断根去凋小区土壤湿度(P<0.05)。物理去除中,土壤湿度从大到小依次为对照小区(24.03%)、去凋小区(20.86%)、断根去凋小区(18.00%)。化学去除中,对照小区(21.60%)和去凋小区(21.47%)土壤湿度显著高于断根去凋小区(18.45%)(P<0.05)。

物理和化学去除林下植被显著降低了断根去凋小区和对照小区0~20 cm土壤有机碳储量(P<0.05),保留林下植被时,对照小区(保留根系和凋落物)0~20 cm土壤有机碳储量显著高于其他小区(P<0.05),说明去除林下植被和凋落物均减少了土壤碳输入。

-

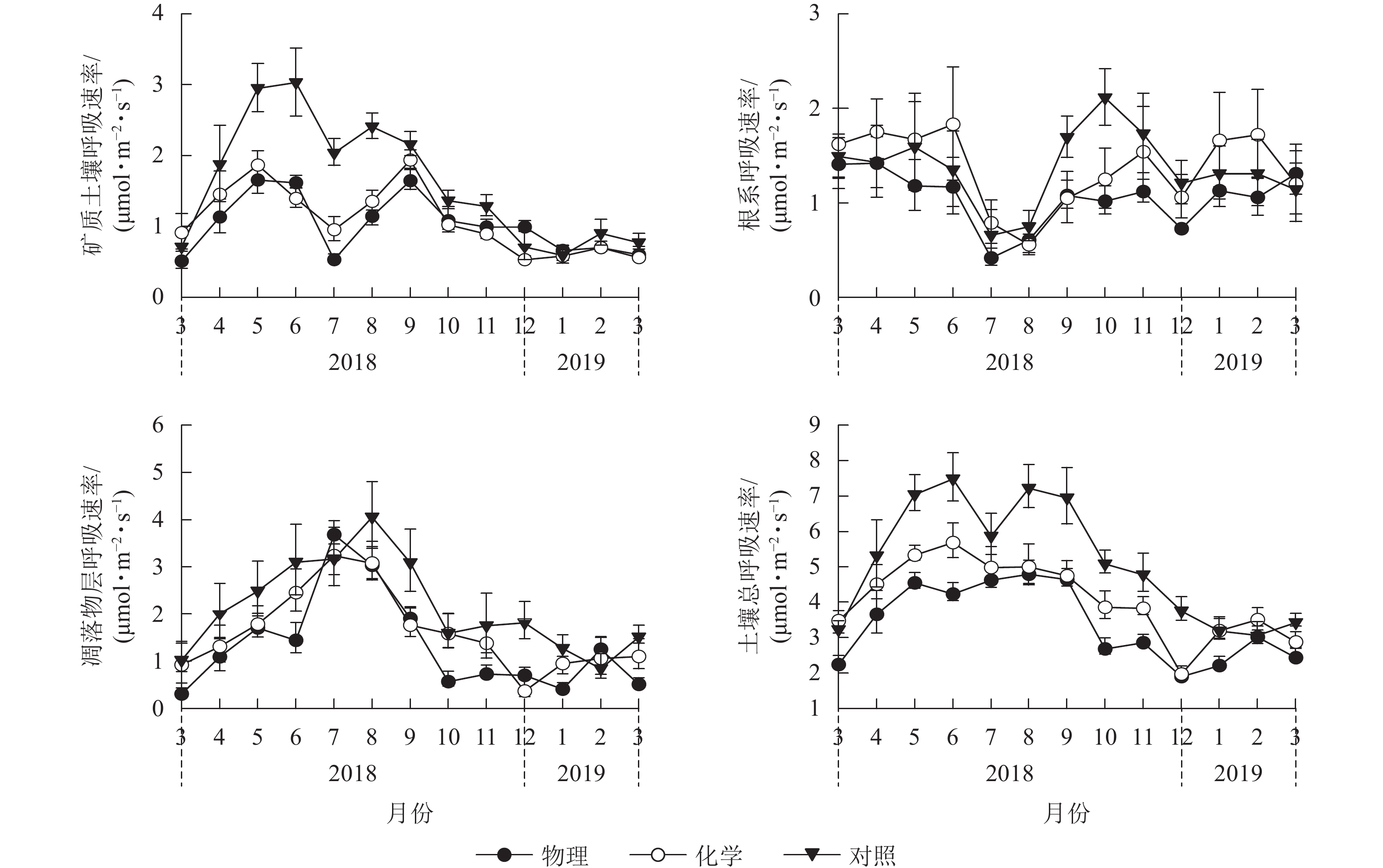

由图1可见:化学去除和对照处理的土壤总呼吸速率月均值在6月最大,物理去除有所推迟,在8月最大。对照样地土壤总呼吸速率月均值在2月最小,物理、化学去除均提前到12月达到最低值。物理、化学去除的矿质土壤呼吸速率及根系呼吸速率在7月骤降,凋落物层呼吸速率则在7月有较大幅度升高,升降幅度差异使得物理、化学去除的土壤总呼吸速率出现差异性变化趋势。

Figure 1. Inter-monthly change of soil respiration and its components in different understory treatments

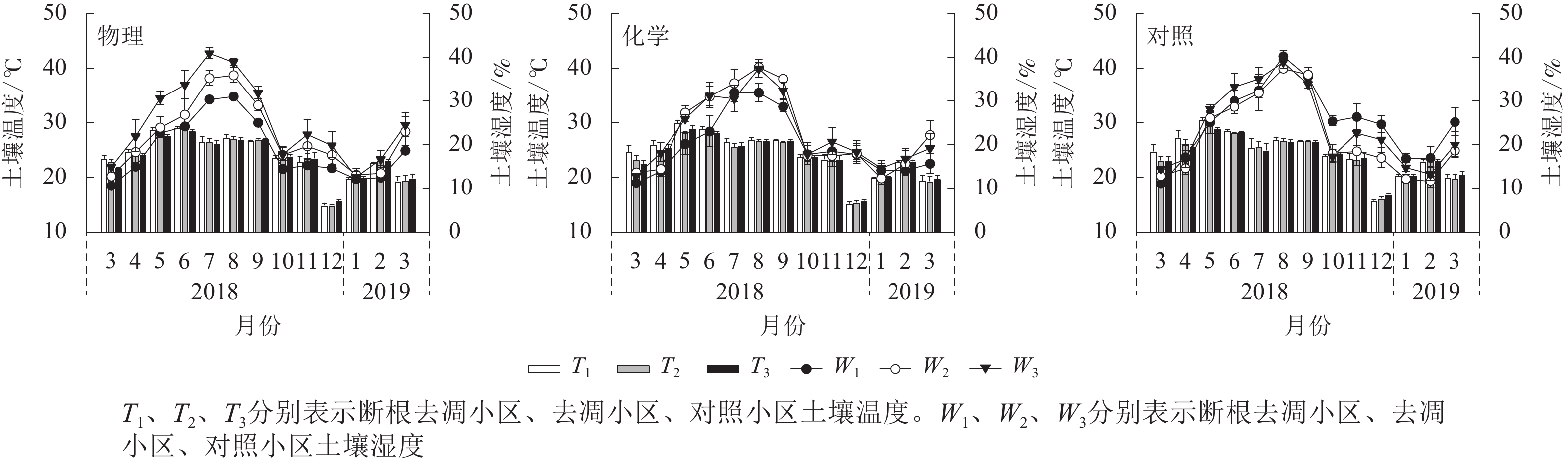

土壤温度、湿度月动态变化均表现出先升后降的趋势(图2)。物理去除的各小区土壤温度均在6月最高,化学去除及对照各小区均在5月最高。不同处理土壤温度最低值均出现在12月。各处理土壤湿度最高值均出现在7—8月,最低值出现在3月和翌年1—2月。

-

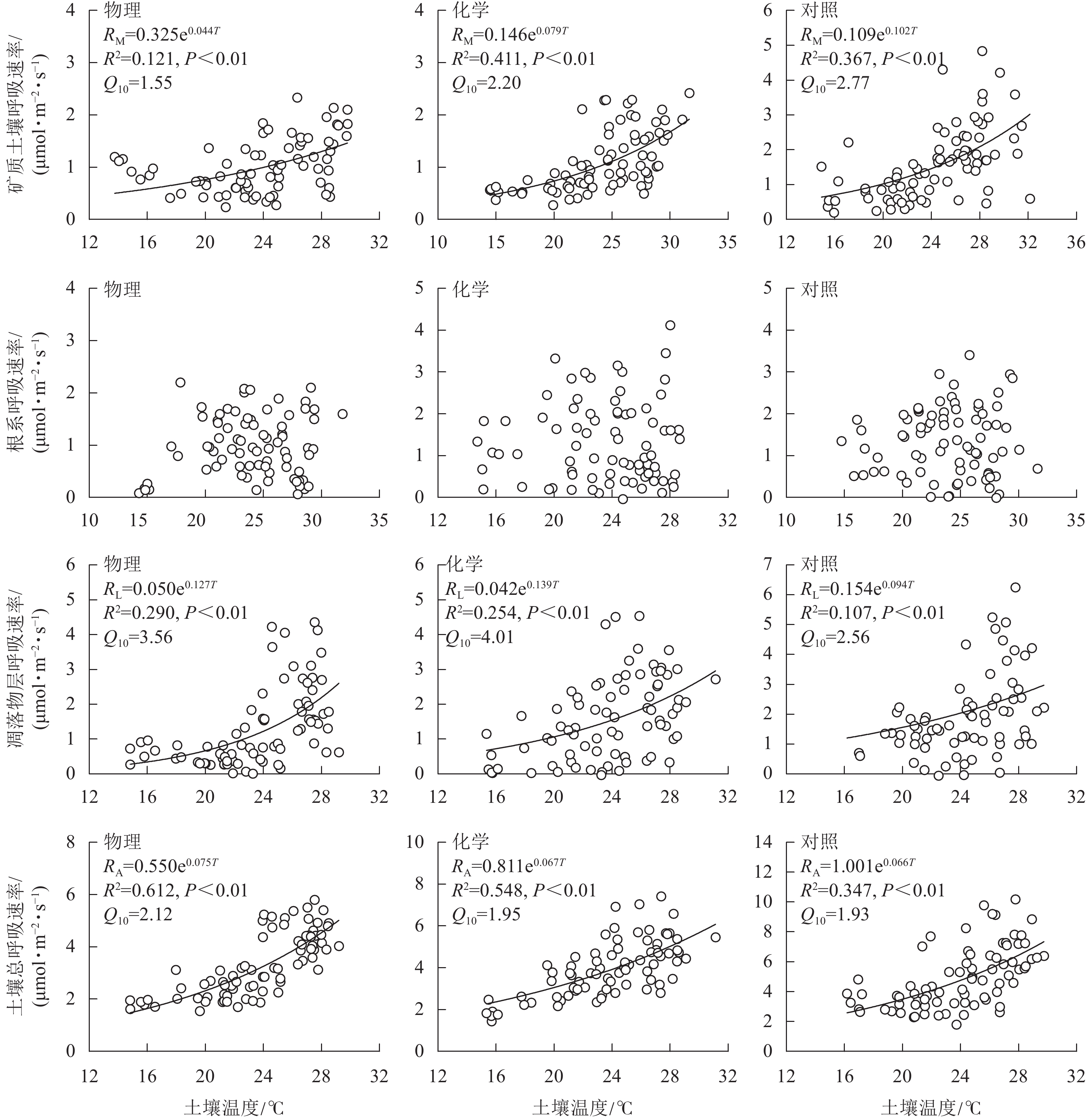

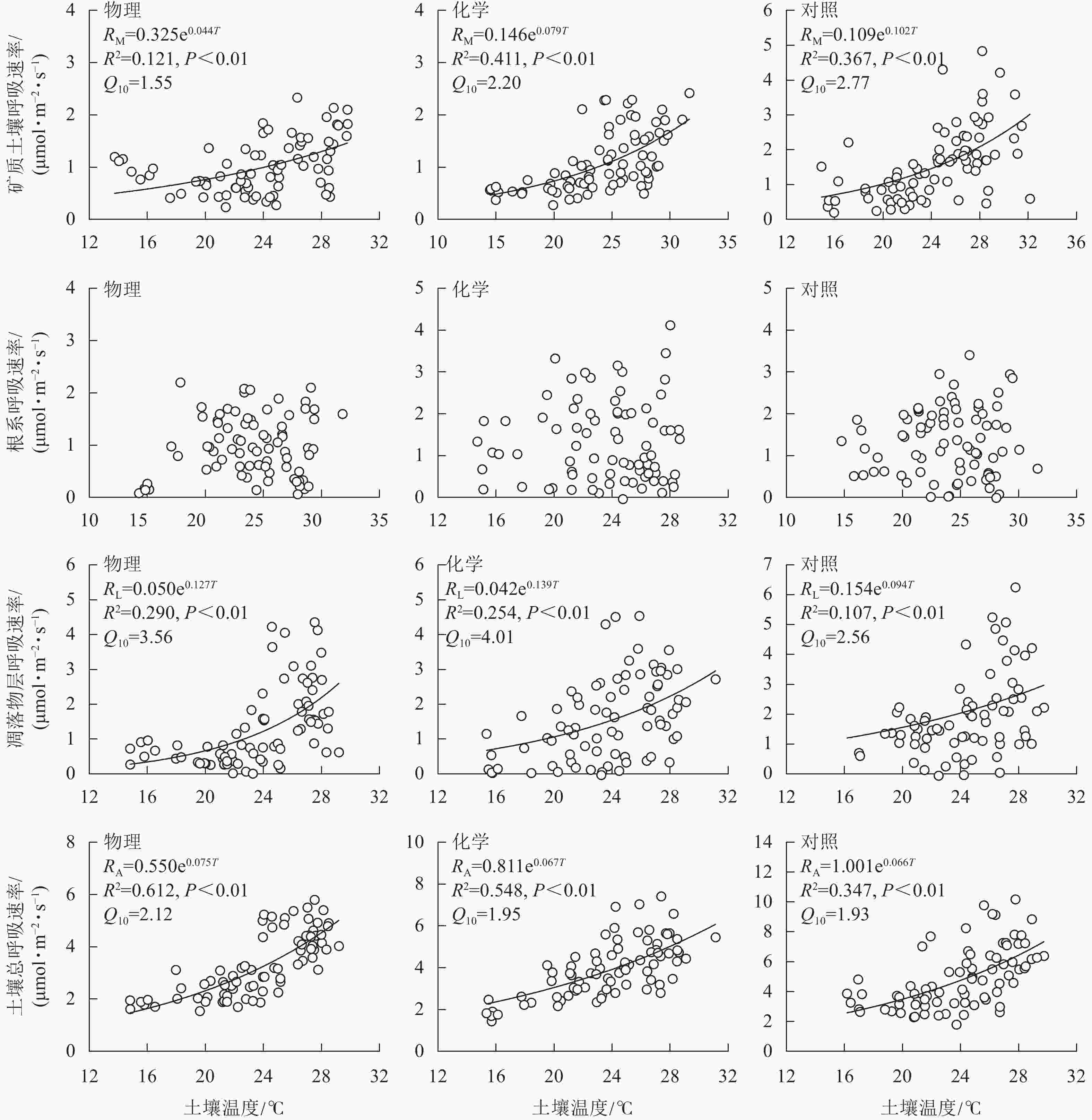

土壤总呼吸速率、矿质土壤呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率与土壤温度呈极显著正相关(P<0.01),根系呼吸速率与土壤温度无显著相关性(P>0.05)。由图3可知:不同处理土壤温度对呼吸速率变化的解释能力差异较大。物理和化学去除的土壤温度分别能解释土壤总呼吸速率变化的61.2%和54.8%,高于对照(34.7%);化学去除的土壤温度能解释矿质土壤呼吸速率变化的41.1%,高于对照(36.7%)和物理去除(12.1%);物理和化学去除的土壤温度分别能解释凋落物层呼吸速率变化的29.0%和25.4%,高于对照(10.7%)。与对照相比,林下植被去除增大了土壤总呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率的温度敏感性系数,减小了矿质土壤呼吸速率温度敏感性系数。矿质土壤呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率温度敏感性系数均为化学去除高于物理去除,土壤总呼吸速率温度敏感性系数为物理去除高于化学去除。

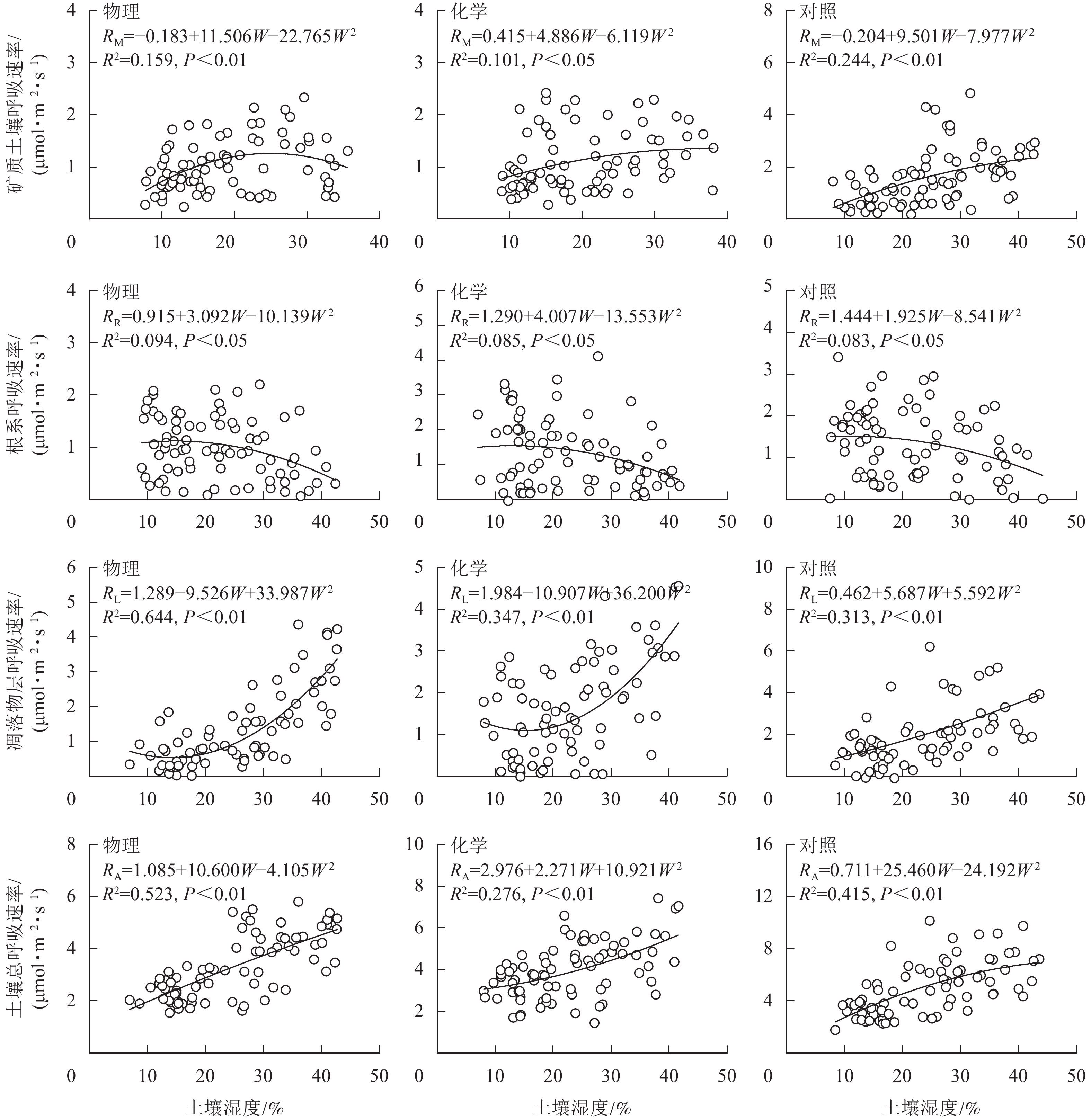

从图4可知:根系呼吸速率与土壤湿度存在显著负相关关系(P<0.05),矿质土壤呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率和土壤总呼吸速率均与土壤湿度存在极显著正相关关系(P<0.01)。土壤总呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率与土壤水分的拟合模型优于矿质土壤呼吸速率和根系呼吸速率。物理去除的土壤水分能解释土壤总呼吸速率变化的52.3%,高于对照(41.5%),而化学去除(27.6%)则低于对照。

-

由表3可知:不同处理土壤温度与湿度的协同作用能更好地解释矿质土壤呼吸速率、根系呼吸速率、土壤总呼吸速率的变化规律,但土壤湿度对凋落物层呼吸速率变化的解释能力高于土壤温度以及土壤温湿度的协同作用。物理和化学去除降低了土壤温湿度协同作用对矿质土壤呼吸速率变化的解释能力,分别降低了29.9%和15.9%。物理和化学去除土壤温湿度协同作用对根系呼吸速率变化的影响相反,物理去除使土壤温湿度对根系呼吸速率的解释能力提高了21.9%,化学去除使土壤温湿度对根系呼吸速率的解释能力降低了8.1%。物理和化学去除提高了土壤温湿度协同作用对土壤总呼吸速率的解释能力,分别是对照的1.32和1.07倍。

项目 物理 化学 对照 α β γ δ ε α β γ δ ε α β γ δ ε 矿质土壤呼吸 数值 2.199 −0.344 9.420 0.009 −22.165 −2.261 0.055 5.728 0.001 −10.379 −4.440 0.136 12.418 −0.001 −17.571 标准误 1.432 0.119 3.871 0.003 9.052 1.287 0.103 3.343 0.002 7.436 1.484 0.120 3.092 0.003 6.010 R2 0.318 0.458 0.617 P <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 根系呼吸 数值 −9.304 0.721 7.645 −0.015 −21.526 −0.933 0.022 6.023 0.001 −16.117 −2.291 0.152 7.296 −0.003 −21.126 标准误 2.016 0.167 4.539 0.004 9.288 4.259 0.362 7.759 0.008 15.188 3.562 0.294 6.064 0.006 12.192 R2 0.343 0.043 0.124 P <0.001 0.510 <0.05 凋落物层呼吸 数值 0.637 −0.172 −1.395 0.005 12.206 −4.334 0.315 −6.974 −0.005 19.906 2.809 −0.287 2.957 0.006 2.835 标准误 2.386 0.206 3.879 0.005 7.263 3.480 0.290 6.326 0.006 12.451 4.207 0.349 5.758 0.008 10.948 R2 0.594 0.329 0.261 P <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 土壤总呼吸 数值 −0.709 0.064 2.636 0.001 −2.196 −2.115 0.239 0.184 −0.004 1.263 0.303 0.001 4.312 0.001 −4.640 标准误 0.764 0.066 1.242 0.001 2.326 0.863 0.072 1.568 0.002 3.086 1.372 0.114 1.878 0.002 3.571 R2 0.751 0.609 0.571 P <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 说明:R2表示关系模型的拟合优度,即决定系数 Table 3. Relation model of soil respiration against soil temperature and soil moisture

-

林下植被是森林生态系统的重要组成部分,去除林下植被能改变土壤温湿度、养分可利用性和土壤微生物群落结构[7, 25],进而影响土壤CO2通量[26]。本研究中,物理和化学去除林下植被显著降低了土壤总呼吸速率,这与王文杰等[27]、WANG等[12]和WU等[15]的研究结果相似。相比于对照,物理和化学去除均使土壤总呼吸速率显著降低,且物理去除的土壤总呼吸速率显著低于化学去除。物理和化学去除使矿质土壤呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率显著降低,但2个处理间无显著差异。化学去除对根系呼吸速率无显著影响。因此,物理去除通过影响3个组分(矿质土壤呼吸速率、根系呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率)造成土壤总呼吸速率出现显著差异性变化,化学去除通过影响2个组分(矿质土壤呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率)使土壤总呼吸速率发生显著差异性变化。

物理和化学去除显著降低了矿质土壤和凋落物层呼吸速率,但2种林下植被去除间无显著差异。矿质土壤呼吸速率主要受到土壤微生物活动和底物供应的影响。林下植被去除后,地表直接暴露,会影响林下植被对水热的调节作用。通常情况下,当土壤含水量很低时,微生物活动受到抑制,且不易获得呼吸所需的底物(底物的扩散性在某种程度上取决于水分的运移)[28]。本研究表明:断根去凋小区土壤平均温度与对照无显著差异,而土壤平均湿度显著低于对照,因而造成矿质土壤呼吸速率显著降低,可能是土壤微生物活动受到土壤湿度限制。凋落物分解产生CO2的过程受到温度和水分的共同作用[29−30]。本研究中对照小区土壤温度和湿度均未产生显著变化,故凋落物层呼吸速率低于对照样地,可能影响因素有:①林下植被去除或死亡后,由草本和灌木产生的凋落物量有所减少。②凋落物的分解包括淋溶、破碎化和化学改变,破碎化是土壤动物将大块凋落物进行裂解的过程,化学组成的变化则主要是细菌和真菌活动的结果。林下植被去除导致土壤动物和微生物生境丢失或改变,引起凋落物层分解者种群发生变化,进而影响凋落物层分解速率。③林下植被去除后,凋落物层可能受到更高的光辐射,进而影响木质素的光降解速率[31−32]和微生物活性[33−34]。

根系生物量和个体根呼吸速率(单位时间生物量释放的CO2)是影响根呼吸量的主要因素[35−36]。本研究中,物理去除林下植被并移除剩余物后,直接降低了地下的活根生物量,导致根系呼吸速率降低。化学去除林下植被后未移除植物残体,会提供养分促进剩余植被的生长,使得活根生物量增加,进而提高剩余植物根系呼吸速率,故化学去除对根系呼吸速率未产生影响,可能是正负效应叠加造成的[37]。

-

土壤温度、湿度是影响土壤呼吸变化的重要环境因子。本研究中,不同林下植被处理方式下土壤总呼吸速率、矿质土壤呼吸速率和凋落物层呼吸速率均与土壤温度存在显著或极显著正相关关系,与土壤温度月均值变化趋势相似。根系呼吸速率与土壤温度相关不显著,与土壤湿度显著负相关,并在土壤湿度月均值达到最高值时根系呼吸速率最低(7—8月),这与相关研究结果不同[38]。REY等[39]研究发现:土壤湿度在最高或者最低时会成为土壤呼吸的主要调控因素,由于本研究区地处北热带湿润大区雷琼区北缘,年均降水量大,旱雨季明显,可能导致土壤湿度成为根系呼吸速率的主要限制因素。

土壤总呼吸速率、矿质土壤呼吸速率与土壤温度湿度的双变量线性模型最优,凋落物层呼吸速率与土壤湿度的单变量线性模型最优,说明研究地土壤总呼吸速率和矿质土壤呼吸速率的时间变化受到土壤温度、湿度综合影响,凋落物层呼吸速率的时间变化主要受到土壤湿度的影响。竹万宽[40]对不同树种桉树人工林土壤总呼吸研究表明:土壤温度和湿度双因子交互作用可以解释土壤呼吸变异的44.8%~83.9%。本研究中,不同处理土壤温度、湿度综合作用能解释土壤总呼吸速率变化的57.1%~75.1%,与以往研究结果[40]相符。林下植被去除增强了土壤温度、湿度对土壤呼吸时间变化的解释能力,且物理去除高于化学去除,可能是物理去除林下植被并移除剩余物导致利于土壤稳定性的缓冲层缺失,物理屏障作用(减轻降水和径流的冲击)和热绝缘作用(避免土壤过热过冷)等减弱[41],进而引起土壤呼吸对温度和湿度变化产生剧烈响应。

土壤温度和湿度能解释的矿质土壤呼吸速率变化从大到小依次为对照(61.7%)、化学去除(45.8%)、物理去除(31.8%),原因可能是林下植被去除减少了矿质土壤呼吸的底物供应,底物供应不足作为主要限制因素,减弱了微生物分解活动对土壤温度和湿度变化的响应程度,物理去除相比于化学去除在更大程度上降低了底物供应。土壤湿度能解释凋落物层呼吸速率变化的31.3%~64.4%,远高于土壤温度,可能是研究区旱雨季分明,凋落物层缺乏土壤成分,难以保持水分,凋落物分解速率对水分变化更为敏感[42]。

HAMDI等[43]研究发现:全球陆地生态系统土壤呼吸的温度敏感性系数(Q10)均值为2.6±1.2,森林生态系统Q10为2.5±0.2。本研究中,Q10为1.93~2.12,均低于全球水平,但高于中国亚热带森林Q10值(1.86)[44]。林下植被去除后,土壤总呼吸速率对温度的敏感程度均高于对照,这与夏秀雪等[21]、WANG等[12]的研究结果类似。土壤呼吸对温度的敏感性取决于树木根系和土壤微生物呼吸对温度的响应程度,两者对温度变化表现出不同程度的敏感性[45],而根呼吸温度敏感性目前存在不同研究结论[46]。本研究中,根系呼吸对温度的敏感性远低于矿质土壤呼吸和凋落物呼吸,相比于土壤温度,根系呼吸对土壤湿度、植物物候变化及光合作用底物供应[47]的响应更为迅速。物理去除相比于化学去除降低了矿质土壤呼吸对温度的敏感性,物理去除林下植被并移除剩余物在更大程度上减少了土壤有机质的输入,底物供应可能作为主要限制因素使得矿质土壤呼吸对温度变化的敏感性降低。凋落物呼吸的温度敏感性主要与其腐朽分解程度相关[47]。物理去除林下植被减少了凋落物量,直接改变了土壤的水热条件,相比于化学去除,物理去除的凋落物呼吸对温度变化的响应可能受到更多因素的共同影响,进而引起不同处理温度敏感性差异。

研究表明:林下植被去除能显著降低土壤有机碳[20],而土壤呼吸则受到土壤有机质中碳底物的调控[48]。本研究中,土壤总呼吸随林下植被的去除而显著降低,与土壤碳储量呈现一致的变化规律。此外,去除林下植被会不同程度地降低凋落物的分解速率[49],进一步减少有机碳的输入量。可见,林下植被去除通过改变林下生物和非生物因子共同作用于土壤呼吸。

-

物理和化学去除尾巨桉人工林林下植被降低了土壤有机碳储量、土壤总呼吸速率、矿质土壤呼吸速率、凋落物层呼吸速率,且物理去除的土壤总呼吸速率显著低于化学去除。土壤总呼吸速率和矿质土壤呼吸速率的时间变异受到土壤温度和湿度双因素的综合影响;凋落物呼吸速率时间变异主要由土壤湿度调控;根系呼吸速率与土壤温度无显著相关性,与土壤湿度显著负相关。本研究表明:林下植被去除通过改变林内生物和非生物因素共同作用于土壤呼吸,且物理去除林下植被相比于化学去除能更大程度降低桉树人工林土壤总呼吸速率,减少森林土壤碳排放,但会在一定程度上影响土壤碳储量。

Response of soil respiration to understory vegetation management in Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis plantation

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220138

- Received Date: 2022-01-25

- Accepted Date: 2022-08-11

- Rev Recd Date: 2022-07-25

- Available Online: 2023-01-18

- Publish Date: 2023-01-17

-

Key words:

- understory vegetation removal /

- soil respiration /

- soil temperature /

- soil moisture /

- Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis plantation

Abstract:

| Citation: | ZHU Wankuan, XU Yuxing, WANG Zhichao, et al. Response of soil respiration to understory vegetation management in Eucalyptus urophylla × E. grandis plantation[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2023, 40(1): 164-175. DOI: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220138 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: