-

美国红枫Acer rubrum为无患子科Sapindaceae槭树属Acer高大落叶乔木,秋季叶片呈现艳丽的红色,具有很高的观赏价值,在中国多地都有引种栽培[1−3]。美国红枫叶色主要与细胞色素含量和比例有关。色素主要包含叶绿素、类胡萝卜素及类黄酮三大类[4],其中类黄酮中的花青素是叶片变红变紫的关键色素[5],其合成途径是通过苯丙氨酸解氨酶等一系列酶促反应将苯丙氨酸转化为花青素[6];该合成过程受到基因调控和外界环境因子的共同影响[4, 7],其中低温条件和光照是影响花青素合成的重要因子,秋季低温天气能促进花青素合成,使叶色更红艳[8−9]。相反,秋季气温过高,花青素合成代谢缺少低温刺激,合成量降低,叶片还未完全转色就已提早落叶,影响观赏价值[10−11]。西南低海拔地区秋季气温普遍较高,重庆10月平均气温仍保持在20 ℃左右。吴琰琰等[8]研究表明:气温过高会抑制美国红枫叶片转色过程中花青素合成和营养物质吸收再利用,导致引种的美国红枫叶片不红、提早落叶等问题。

氮素是影响植物生长和衰老的重要因素,较低的氮水平会加速衰老基因的表达,而适当施氮能增加穗叶的氮浓度,延缓叶片衰老[12]。同时,氮素是影响花青素合成代谢的关键元素之一,低氮环境会刺激黄酮类合成途径基因的表达,提高花青素积累[13],而高氮不仅不会促进花青素积累,反而还会抑制花青素的合成[14−16]。本研究利用氮素对植物衰老的调控作用——持续满足植物对氮的需求能减缓植物衰老,适量增加氮能延长绿叶的维持时间[17−18],通过施氮延长美国红枫营养生长时间,延缓衰老,推迟其秋季叶片转色时间,使其转色期与低温相遇,以期提高美国红枫的叶色质量,并延长观赏期,为西南低海拔地区美国红枫科学种植提供参考。

-

研究区位于重庆市北碚区歇马镇西南大学实验农场,该地属于典型的亚热带湿润季风气候,雨量充沛,海拔为198 m,2024年平均气温为20.1 ℃,9月最高气温为43.6 ℃,1月最低气温为1.2 ℃,年均日照时数为1 299 h,总降水量为465.2 mm,土壤类型为紫色土。土壤理化性质为:pH 6.6,有机质9.73 g·kg−1,全氮0.78 g·kg−1,全磷0.47 g·kg−1,全钾12.05 g·kg−1,铵态氮0.61 mg·kg−1,硝态氮4.72 mg·kg−1,速效磷27.79 mg·kg−1,速效钾12.05 mg·kg−1,田间最大持水量24.54%。

-

采用田间试验,于2024年1月在歇马试验田统一除草整地,在2024年2月初选取健康、长势基本一致(高140~160 cm、地径15~17 mm)、无病虫害的2年生轻基质苗美国红枫栽种品种‘红冠’A. rubrum ‘Red Crown’,划分出5 m×20 m的共5个小区,每个小区之间至少间隔1 m,以株行距2.5 m随机栽植,移栽时在底部施加2 kg有机肥(重庆三峡建设集团忠县柑桔有限公司的柑橘皮渣有机肥)作为基肥,移栽后缓苗1个月。

采用单因素试验(表1),肥料为尿素(总氮质量分数为46.40%)、过磷酸钙(P2O5质量分数为12%)、硫酸钾(K2O质量分数为20%)。磷肥(P)和钾肥(K)均按全年施用量10 g·株−1进行施肥。通过盆栽预试验发现施氮量超过200 g·株−1会抑制美国红枫生长,因此,氮肥按尿素施用量设置5个水平,即ck(0 g·株−1)、T1(50 g·株−1)、T2(100 g·株−1)、T3(150 g·株−1)、T4(200 g·株−1)。每处理12株,共60株。于2024年3月开始处理,施肥以少施多次的原则,根据美国红枫的生长规律,3—9月施用量占比,尿素分别为10%、10%、20%、20%、30%、10%、0%;磷肥和钾肥均分别为0%、0%、20%、20%、20%、30%、0%。施肥方式采用环施法。2024年4月初开始按美国红枫生长规律测其生长指标和叶片性状指标;自9月开始观察记录叶片转色时间(即叶片开始转色至转色结束),并测量SPAD (soil and plant analyzer development)值。从ck叶片开始转色至T3、T4叶片转色结束,划分Ⅰ~Ⅵ共6个阶段,其中Ⅰ~Ⅳ阶段分别代表ck的转色前期、转色初期、转色中期和转色末期,Ⅰ阶段叶片转色数量小于5%(转色前期)、Ⅱ阶段叶片转色数量为5%~30%(转色初期)、Ⅲ阶段叶片转色数量为>30%~70%(转色中期)、Ⅳ阶段叶片转色数量>70%~100%(转色末期);由于不同处理导致叶片转色时间不同,Ⅴ和Ⅵ仅分别代表T3、T4的转色中期和转色末期,其中ck的Ⅳ阶段同为T3、T4的转色初期。

处理 尿素/(g·株−1) 磷/ (g·株−1) 钾/ (g·株−1) ck 0 10 10 T1 50 10 10 T2 100 10 10 T3 150 10 10 T4 200 10 10 Table 1. Fertilizer (N, P, K) application program

-

株高和地径通过钢卷尺和电子游标卡尺(精度0.01 mm)测量,采集叶片并去掉叶柄,使用游标卡尺测量叶片厚度,每个处理选取10片叶,用智能叶面积测量系统(YMJ-C,浙江托普云农科技股份有限公司)测定叶面积。称鲜质量后,105 ℃杀青30 min,65 ℃烘干至恒量测量干质量,计算比叶面积。

-

叶片叶绿素、类胡萝卜素采用丙酮-乙醇混合液浸提法提取,花青苷采用体积分数为1%盐酸甲醇溶液浸提[19]、可溶性糖用蒽酮比色法测定[20];用SONY α6000相机在固定机位和光源下,以A4纸为背景对叶片进行拍照,用Matlab软件提取明度(L*)、红绿色度(a*)、黄蓝色度(b*),并计算彩度(C*)[21]。

-

通过便携式SPAD-502叶绿素仪测定叶片SPAD值,绘制SPAD值曲线,同时观察植株整体叶片着色情况,通过SPAD值的变化趋势和叶片着色时间来判断叶片衰老情况[22-23]。通过连续观察美国红枫叶片着色情况,记录观赏期和最佳观赏期(整株2/3叶片变色时为最佳观赏期开始,整株落叶1/2为最佳观赏期结束)。

-

采用Excel 2010进行数据统计,SPSS 22.0进行显著性差异分析(Duncan法进行多重比较);利用Origin 2018制作图表,用R Studio进行相关性分析和热图制作。

-

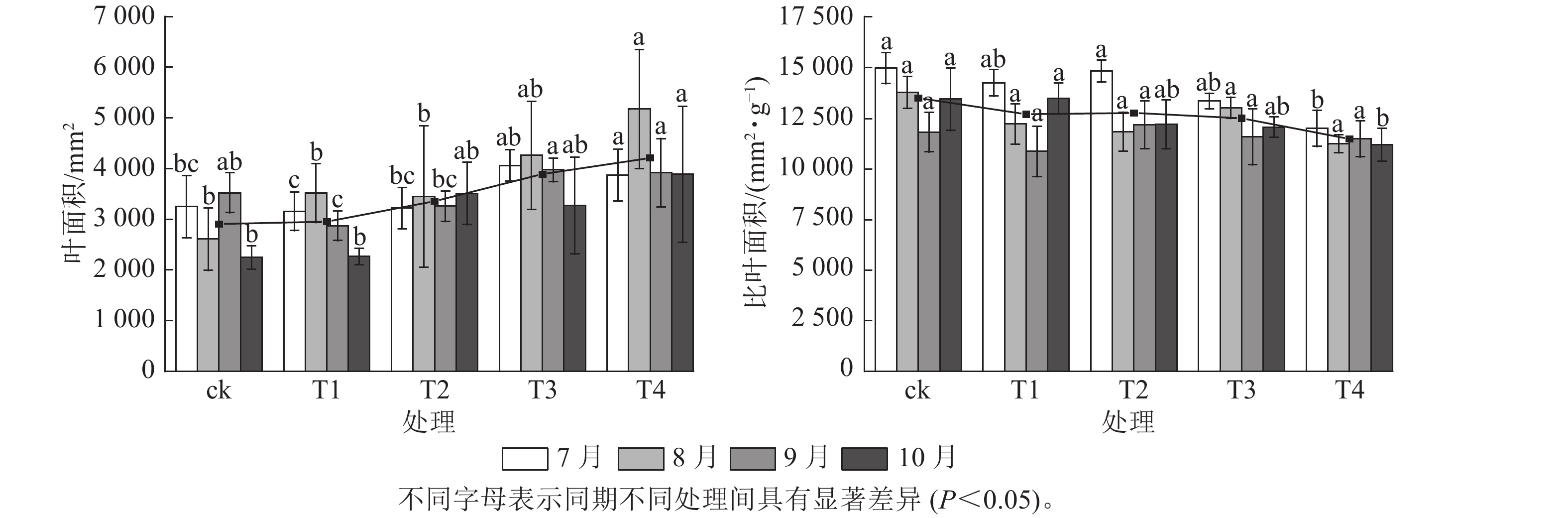

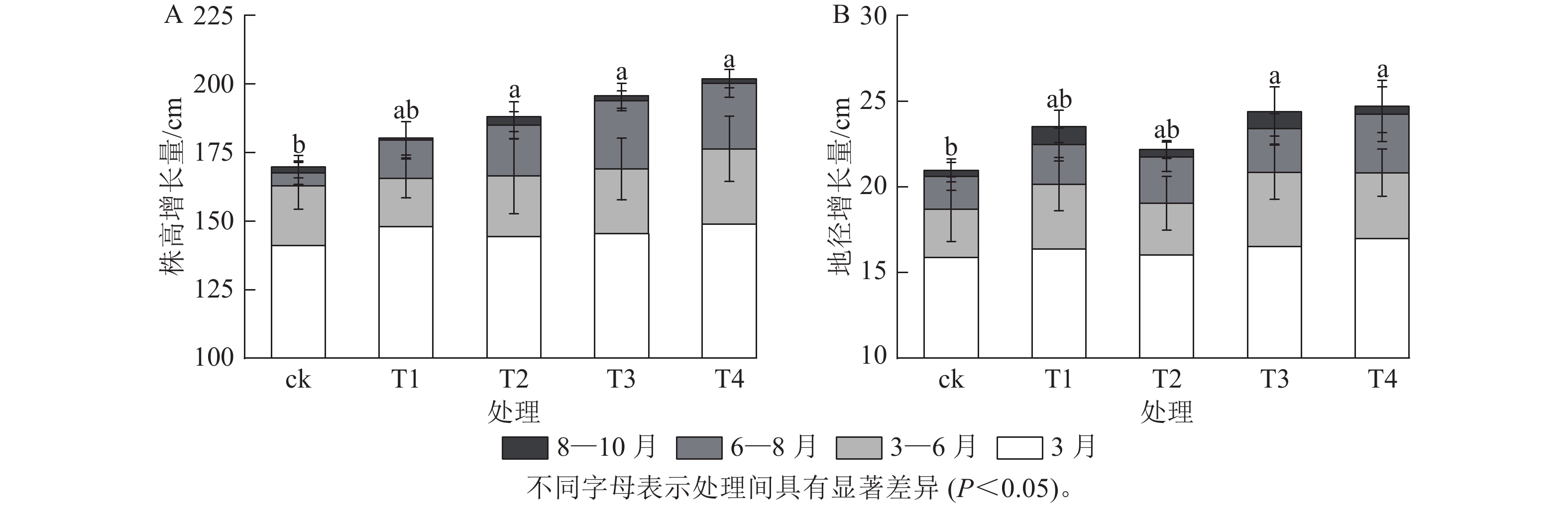

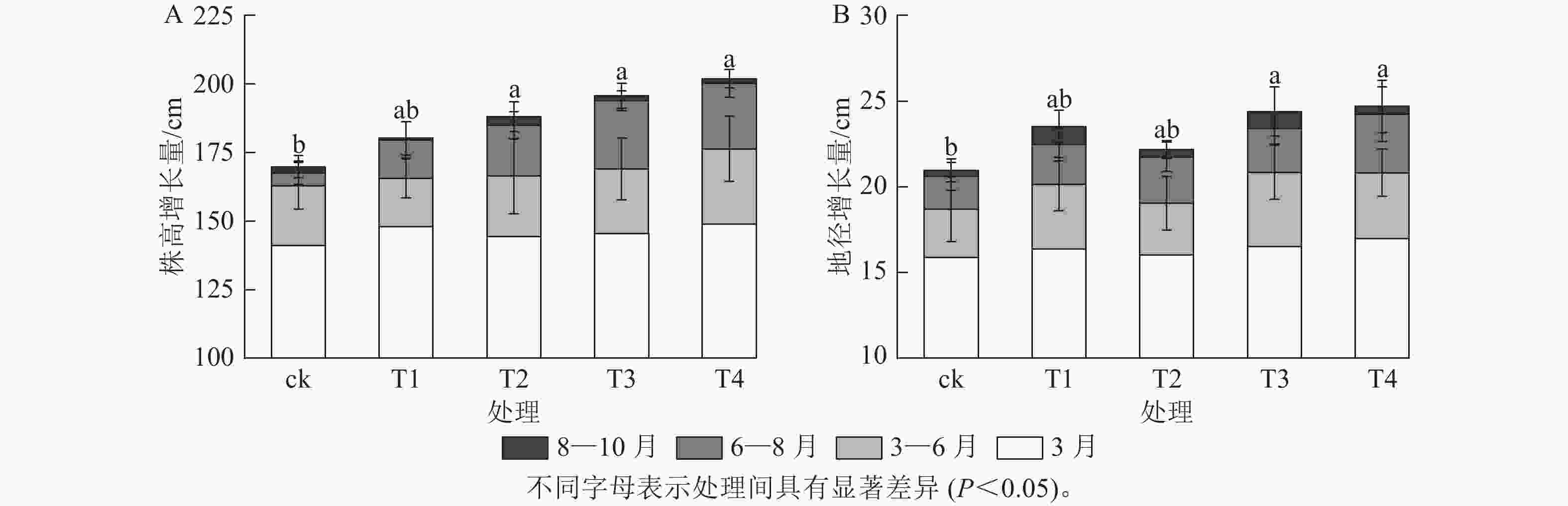

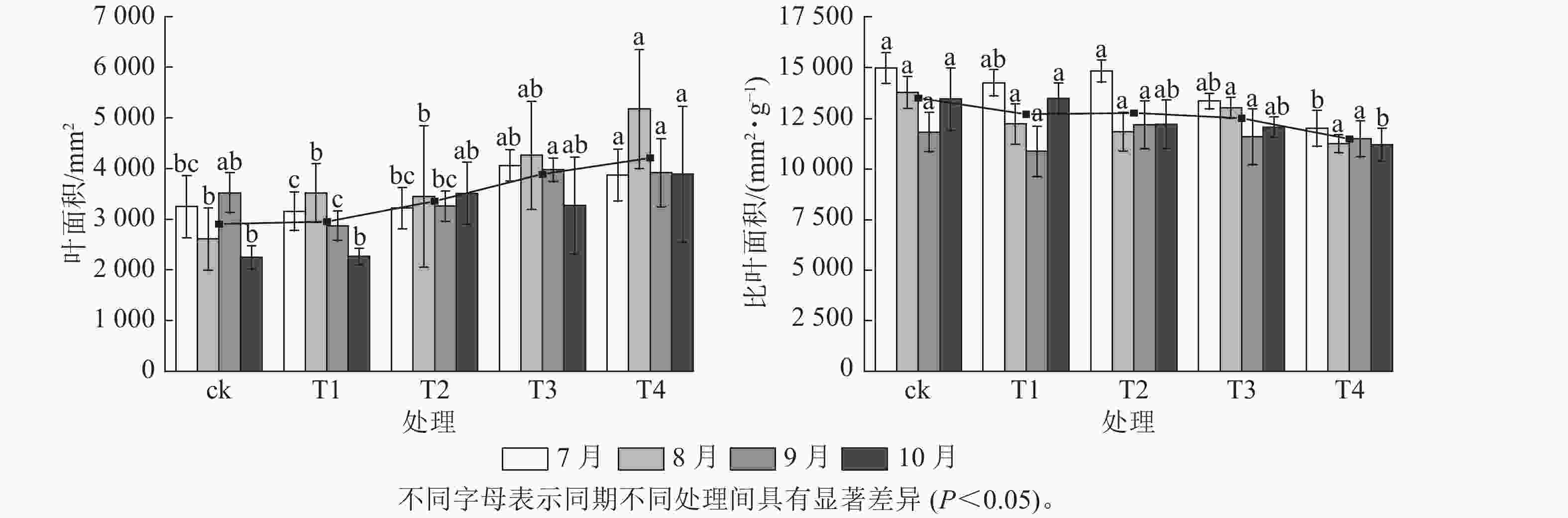

施氮对美国红枫株高和地径的增长具有显著促进作用(图1)。T2、T3、T4的累计株高增长量分别为(43.74±10.07)、(50.25±9.11)和(53.06±8.21) cm,均显著高于ck (P<0.05);T3和T4的累计地径增长量分别为(6.51±2.4)、(6.23±2.3) mm,显著高于ck(P<0.05)。各处理3—6月和8—10月的株高和地径增长量无显著差异;但在6—8月生长关键期,T3[(24.85±3.59) cm]和T4[(23.90±5.10) cm]株高增长量显著高于ck (P<0.05)。由图2可知:总叶面积大小与施氮量呈显著正相关(P<0.05),7—8月T4的叶面积显著高于T2、T1和ck(P<0.05);而比叶面积随着氮施用量增加呈梯度下降,T4的平均比叶面积最小,7月和10月T4的比叶面积显著小于ck (P<0.05)。

-

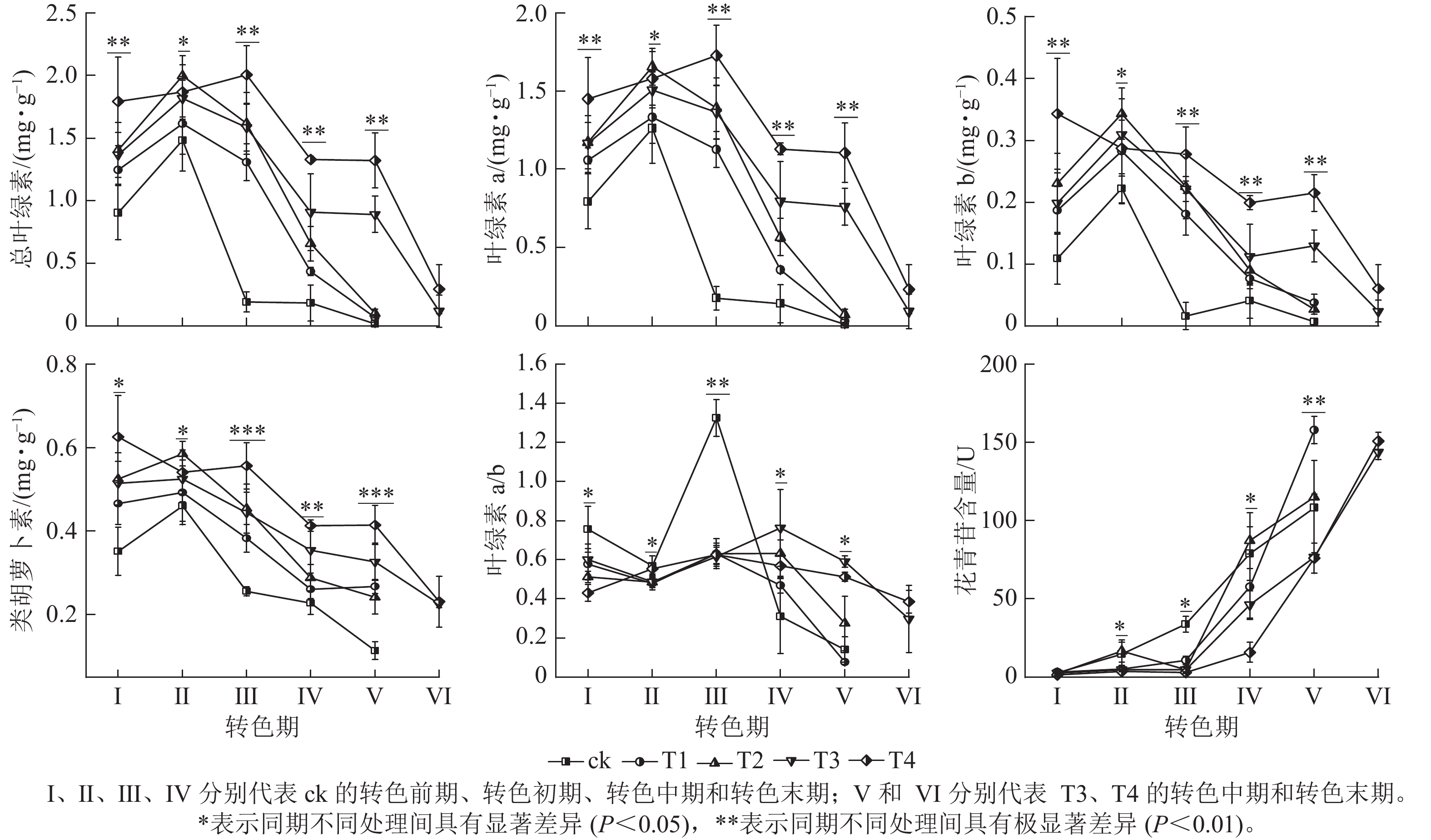

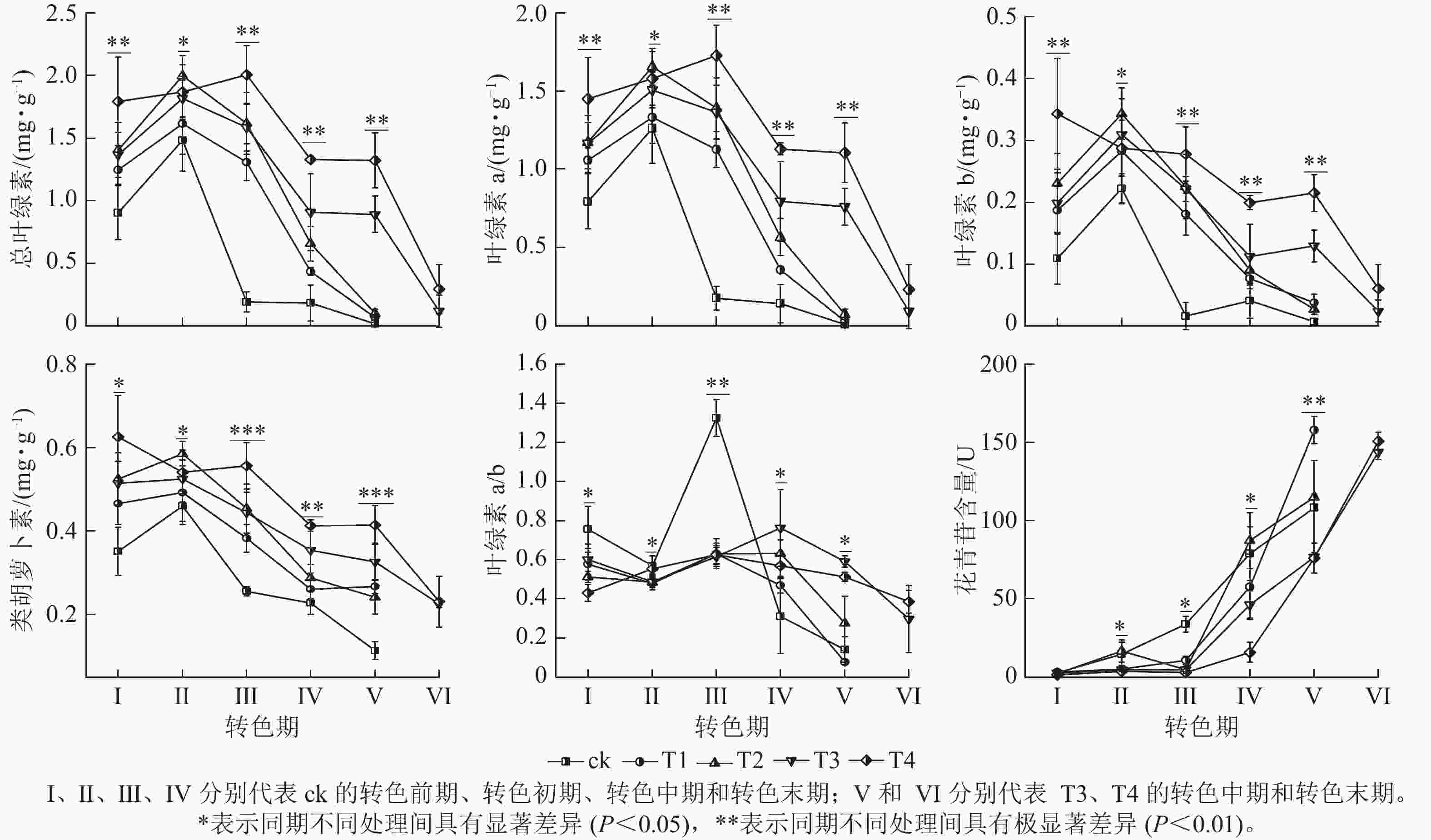

整体上,各组的色素质量分数及变化趋势存在显著差异(图3),其中T4处理的总叶绿素、叶绿素 a、叶绿素 b和类胡萝卜素质量分数相比其他处理在各时期(除Ⅱ期之外)都保持最高水平;在Ⅰ期T4的总叶绿素(1.79 mg·g−1)和类胡萝卜素(0.63 mg·g−1)显著大于ck(P<0.05);进入转色期后,ck的总叶绿素、叶绿素 a、叶绿素b和类胡萝卜素质量分数在Ⅱ期开始快速下降,而T4的总叶绿素和类胡萝卜素质量分数在Ⅱ和Ⅲ期仍保持较高水平,在Ⅳ期才开始下降。各处理叶绿素a/b在Ⅰ、Ⅱ期无显著差别,在Ⅲ期ck的叶绿素a/b(13.24)迅速增加,显著高于其他处理(P<0.05)。呈现该变化可能与ck提早衰老,叶片叶绿素分解速度过快有关。

各处理花青苷含量变化存在明显差异,随着叶片开始转色,各处理花青苷含量不断上升,其中ck叶片最先开始转色,花青苷含量上升速度最快,Ⅲ期ck的花青苷含量显著高于其他处理组(P<0.05);Ⅳ期T1、T2的花青苷含量快速上升,其中T2的花青苷含量超过ck达到最高;Ⅴ期T1组花青苷含量上升最快,此时ck、T1、T2叶片已完全变色并开始落叶;Ⅵ期时,ck、T1、T2已完全落叶,T3和T4叶片完全变色,花青苷含量达到最大值。

-

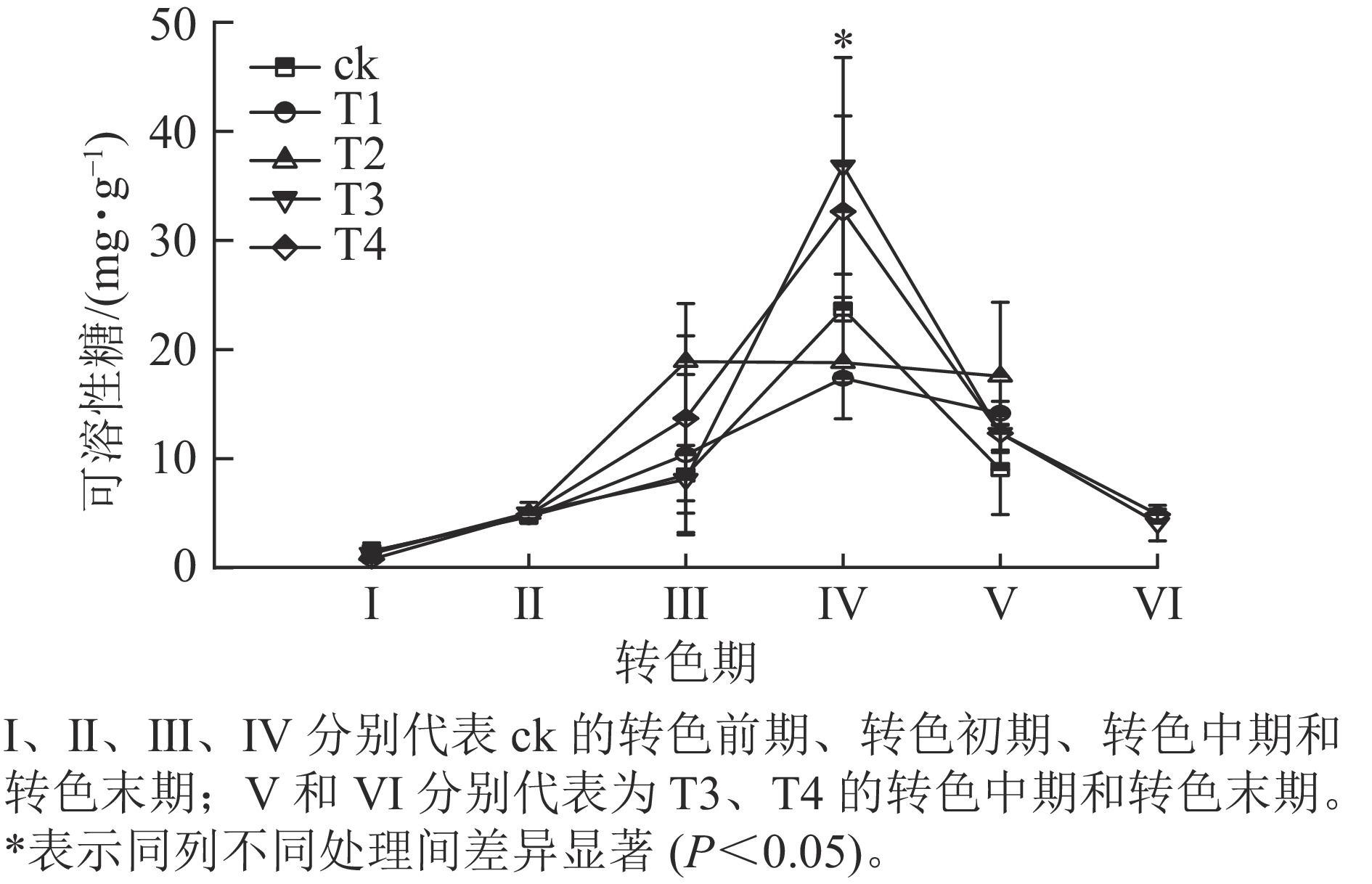

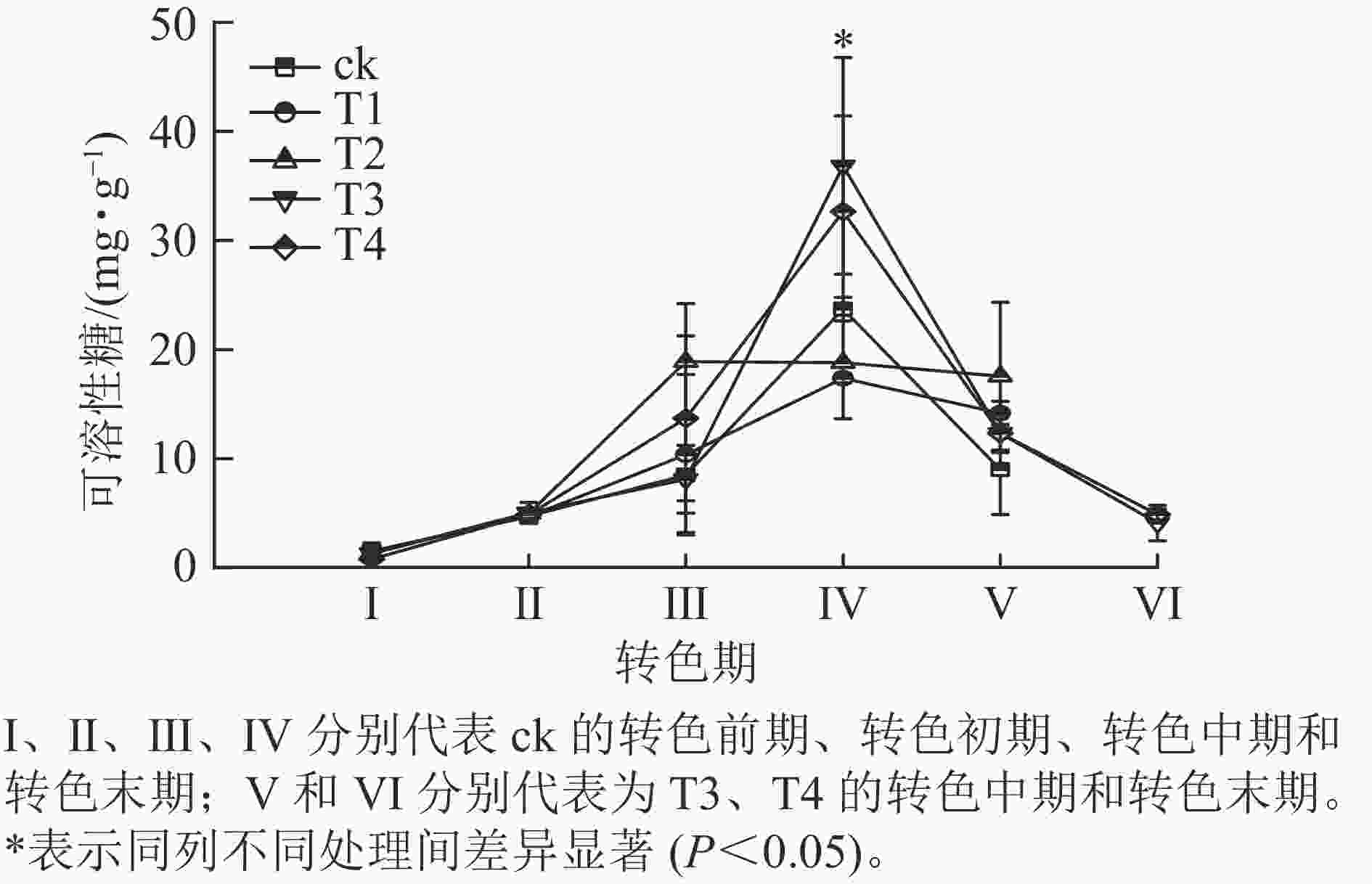

各处理叶片可溶性糖质量分数呈先上升后下降的趋势(图4)。在Ⅰ、Ⅱ期各处理可溶性糖质量分数大致相同,该阶段气温相对较高,各处理叶片刚刚开始衰老转色,可溶性糖质量分数变化差异不显著;进入Ⅲ期,可溶性糖质量分数普遍上升,其中ck的增速最快,可溶性糖增长到20.6 mg·g−1,T2次之,可溶性糖增长到18.9 mg·g−1,此时ck、T1和T2叶片完全转色,而T3和T4仍未开始转色;到了Ⅳ期T3和T4叶片可溶性糖质量分数急速升高,分别增长到了36.8和32.7 mg·g−1,显著超过其他处理(P<0.05);此时T3和T4开始衰老转色,ck、T1和T2叶片受低温刺激开始落叶;Ⅴ期各处理可溶性糖质量分数整体骤降,ck的可溶性糖质量分数降低至9.0 mg·g−1;此时ck、T1和T2处理进入衰老末期,叶片快速脱落,T3和T4进入转色中期;Ⅵ时期T3和T4可溶性糖质量分数继续下降,叶片到达衰老后期,叶片开始脱落。

-

随着转色进程推进,各处理叶色参数和C*的变化各不相同(表2),ck的L*在Ⅰ期显著大于T3,而在Ⅴ期显著小于T3(P<0.05);各处理a*在Ⅰ期差异不显著,但随着叶片转色进程推进,差异逐渐显现;ck的a*在转色期Ⅱ~Ⅴ都显著大于T4(P<0.05);并且ck的a*从Ⅱ期开始逐渐上升,Ⅳ期达到最大值(22.59±3.08);而T4处理a*在Ⅱ、Ⅲ期甚至有所下降,当Ⅳ期才开始上升,Ⅵ期达到最大值(24.35±3.08)。Ⅰ期ck的b*与T3、T4有明显差异,其余时期各处理的b*无显著差异。各处理C*随着叶片转色呈现“V”型变化特征,且各处理间差异显著,在Ⅰ期时,ck的C*与T3、T4有显著差异(P<0.05) ;Ⅳ期时,ck的C*显著大于其他处理(P<0.05) ;T3和T4的C*在Ⅰ~Ⅳ期变化不大,在Ⅴ期急剧下降,而Ⅵ期时又上升,分别达到最大值(29.64±3.19和29.67±4.40)。

转色期 L* a* ck T1 T2 T3 T4 ck T1 T2 T3 T4 Ⅰ 19.87±2.98 a 17.01±3.26 ab 16.14±1.86 b 16.13±1.34 b 15.31±1.04 b −6.55±0.74 a −6.52±1.07 a −6.46±0.79 a −6.96±0.73 a −6.79±0.69 a Ⅱ 16.15±1.70 a 15.88±1.09 a 17.16±0.53 a 16.13±1.04 a 17.01±1.03 a −3.92±1.45 b −0.93±3.64 a −5.56±1.41 bc −6.96±0.73 c −7.11±0.26 c Ⅲ 14.71±4.56 a 15.47±2.88 a 16.65±1.90 a 15.60±1.49 a 16.05±1.79 a 13.52±6.43 a −3.54±4.80 b −10.73±0.70 c −10.11±0.87 c −9.87±0.82 c Ⅳ 16.13±2.15 ab 13.58±2.69 b 15.27±3.02 ab 18.10±0.87 a 17.96±0.42 a 22.59±3.08 a 10.59±3.82 b 0.09±3.53 c −0.85±8.91 c −4.05±3.40 c Ⅴ 13.18±2.59 b 14.16±0.54 ab 9.98±2.57 c 17.34±1.00 a 14.60±2.48 ab 19.95±1.89 a 21.64±1.91 a 15.00±4.61 ab 10.50±6.29 b 0.32±6.12 c Ⅵ 16.92±1.94 17.10±2.62 24.65±2.07 24.35±3.08 转色期 b* C* ck T1 T2 T3 T4 ck T1 T2 T3 T4 Ⅰ 22.42±3.70 a 19.69±3.96 ab 18.89±2.87 ab 16.85±1.64 b 16.01±1.07 b 23.39±3.42 a 20.75±4.08 ab 19.97±2.92 ab 18.23±1.72 b 17.39±1.20 b Ⅱ 18.91±2.73 a 19.18±1.43 a 19.15±0.90 a 16.85±1.64 a 17.30±0.79 a 19.38±2.52 a 19.47±1.17 a 19.98±0.94 a 18.23±1.71 a 18.71±0.72 a Ⅲ 16.56±1.10 a 15.26±1.16 a 17.23±1.68 a 16.29±1.34 a 14.90±1.70 a 21.52±9.94 a 16.06±4.86 a 20.32±1.48 a 19.17±1.59 a 17.87±1.81 a Ⅳ 18.55±3.55 a 12.59±3.36 a 12.90±4.96 a 15.37±2.91 a 17.56±1.39 a 29.26±4.43 a 16.61±4.37 b 13.44±4.23 b 17.00±3.15 b 18.26±1.29 b Ⅴ 14.15±3.52 a 14.08±2.11 a 9.52±3.01 a 10.08±2.96 a 10.32±4.86 a 24.51±3.57 ab 25.83±2.73 a 17.79±5.42 bc 14.71±6.50 c 11.52±5.13 c Ⅵ 16.41±2.87 16.93±3.33 29.64±3.19 29.67±4.40 说明:数值为平均值±标准误。同一变量同一转色期不同字母表示处理间差异显著(P<0.05)。 Table 2. Effects of different nitrogen treatments on leaf color parameters of A. rubrum

-

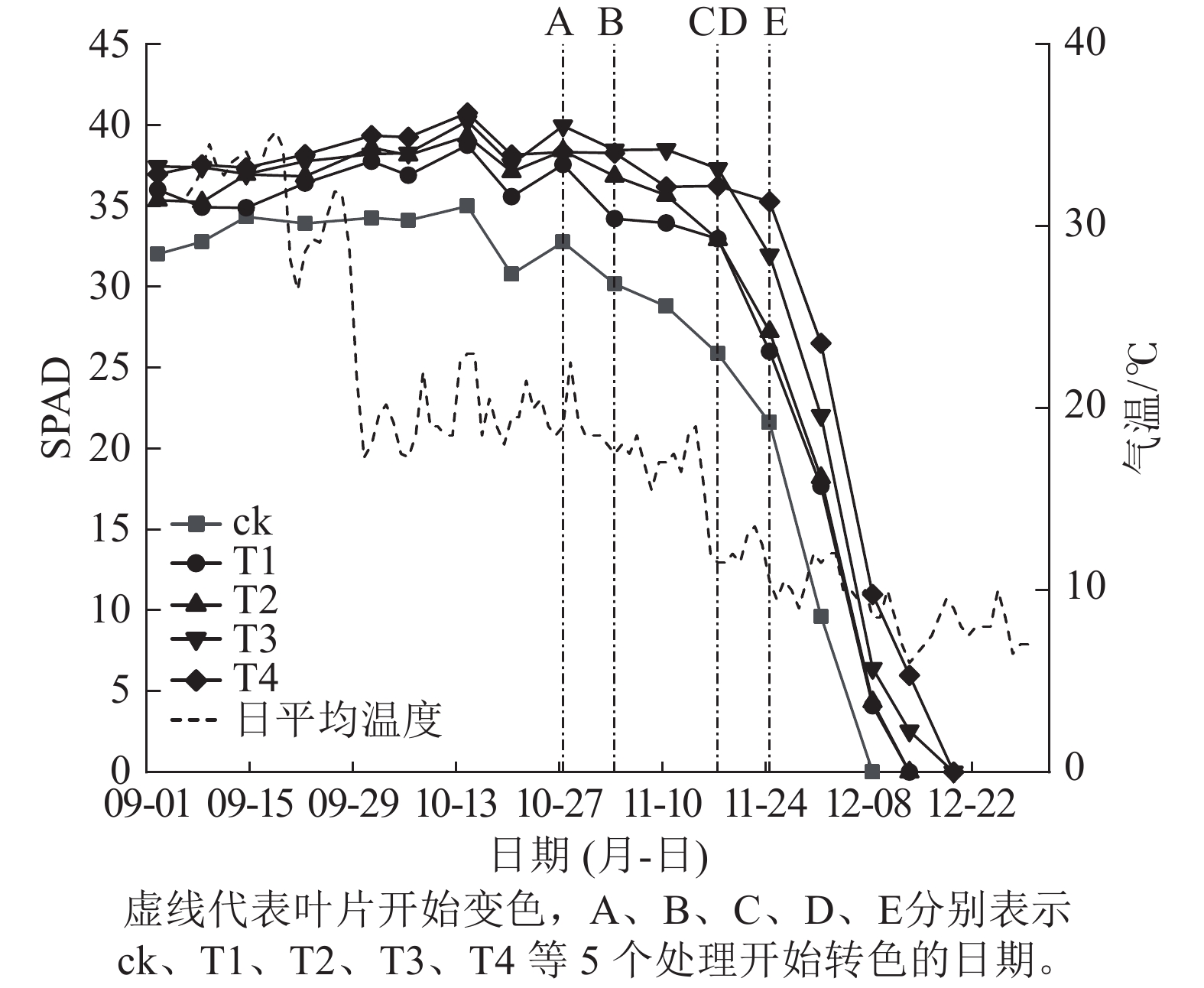

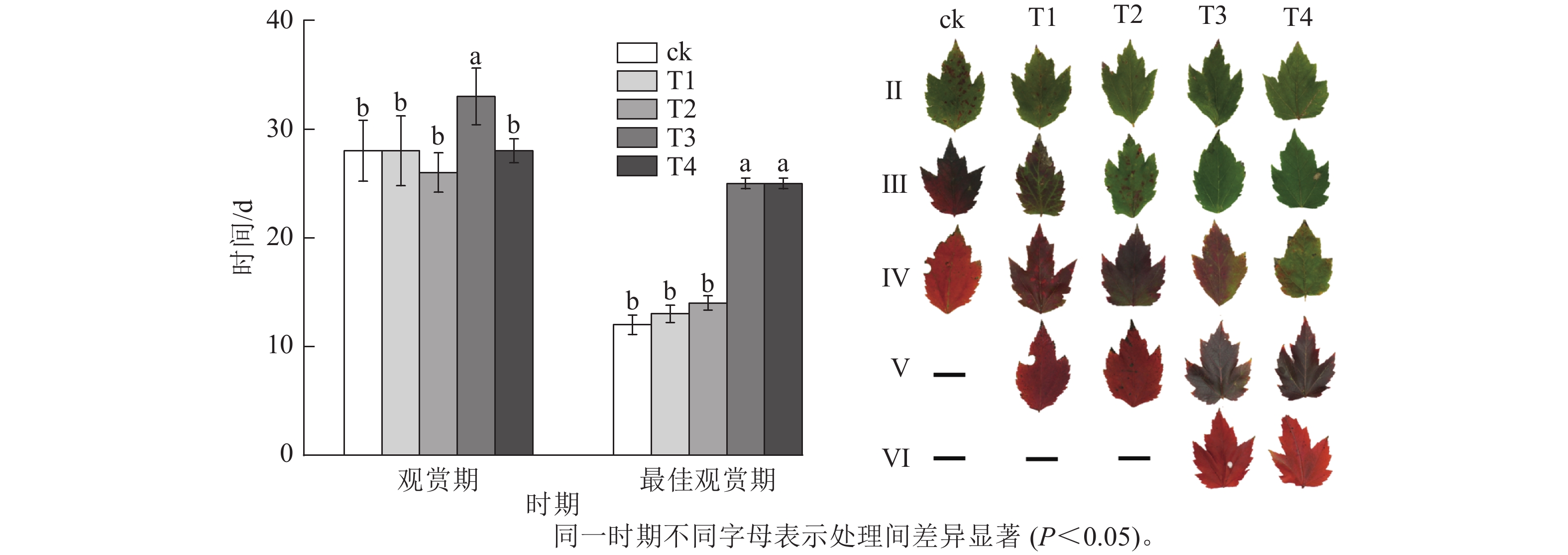

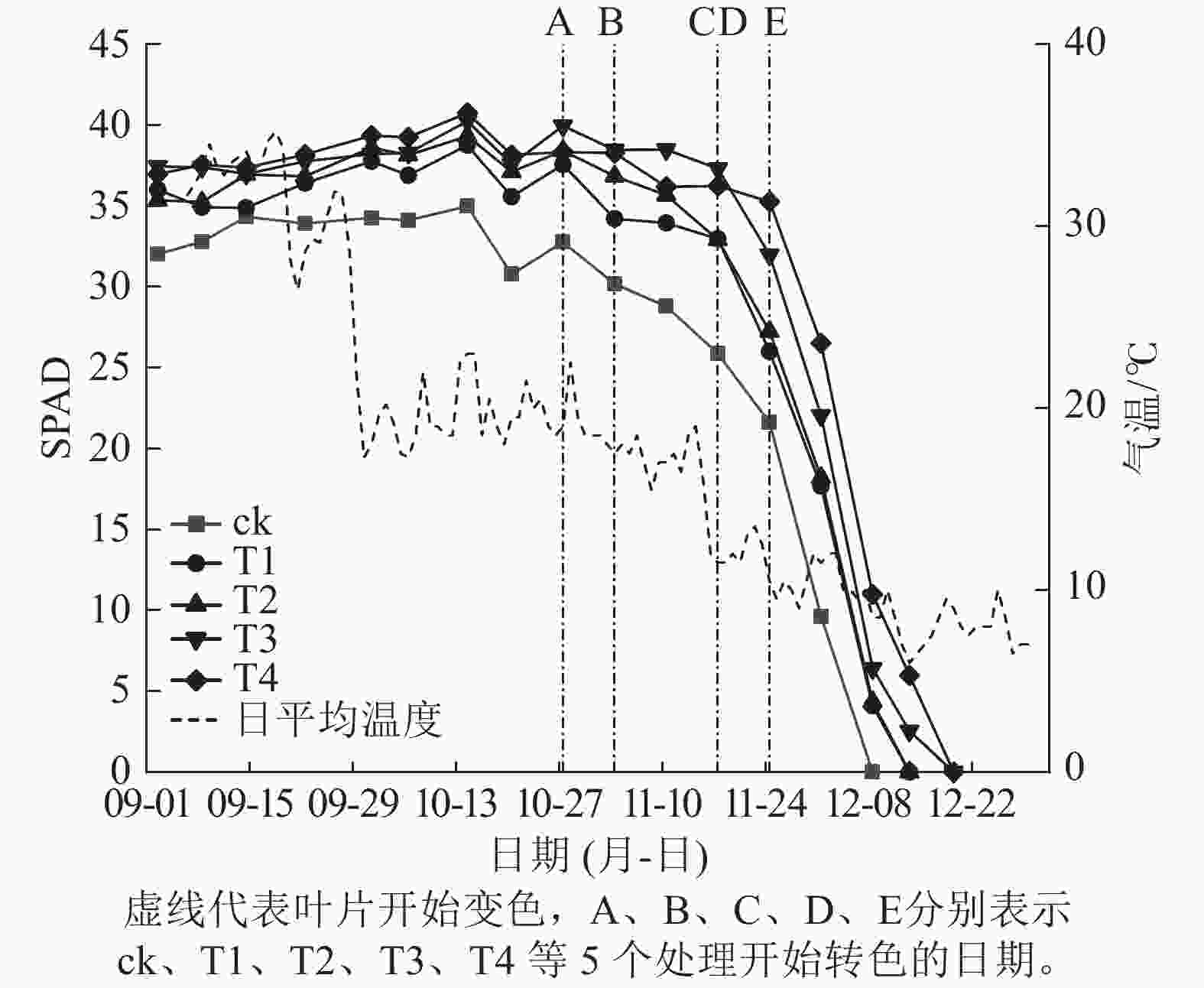

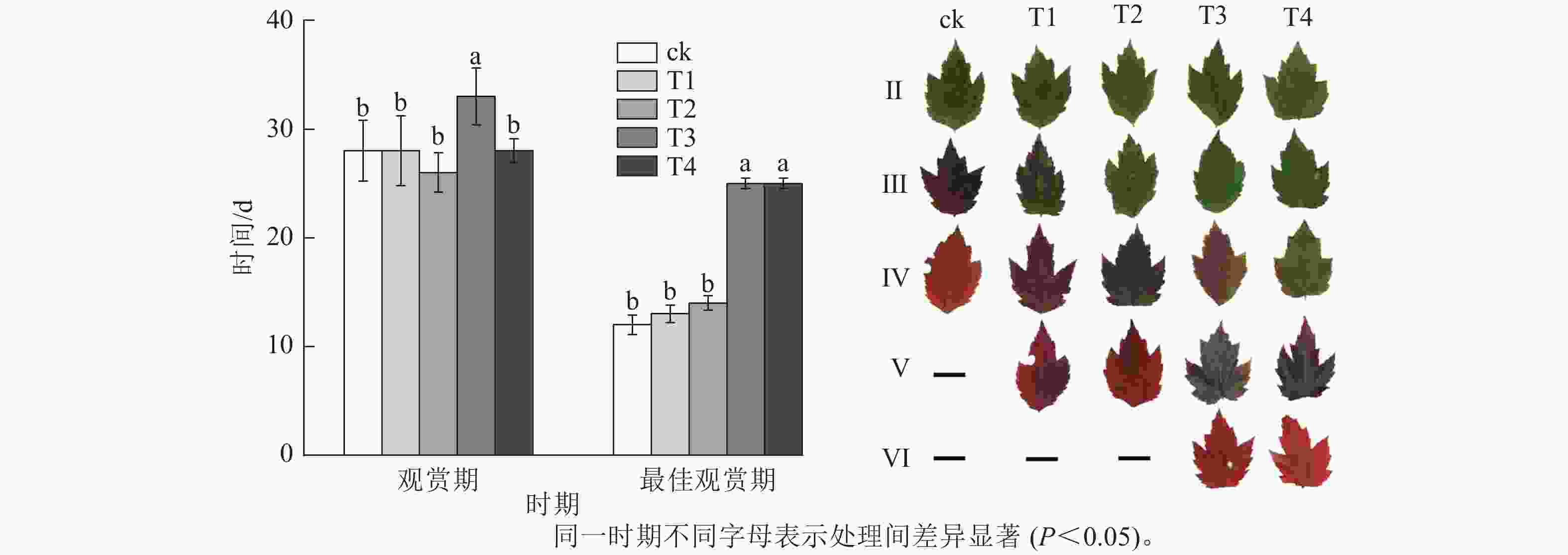

施氮量与美国红枫叶片SPAD值呈正相关(图5),ck总体SPAD值较小,下降最快,叶片开始转色时间(A)最早;T1~T4的SPAD值随施氮量增加呈梯度增加,其中T4的SPAD值一直保持较高水平,下降时间较晚,叶片最晚开始转色(E)。施氮量对美国红枫叶片转色和气温之间响应也有影响,ck、T1分别在10月底和11月初叶片开始逐渐转色,此时日平均气温保持在17~22 ℃,而当气温骤降至10 ℃左右后,T2和T3叶片才开始转色;而T4遇到低温后SPAD值未立刻下降,叶片开始转色时间为11月下旬。从图6可以看出:各处理不同时期的叶色变化差异明显,叶色随着时间呈现梯度性变化。T3的观赏期长短(33 d)与其他处理有显著差异(P<0.05);ck和T1转色时间较早,遇到低温条件后叶片提早落叶,导致最佳观赏期较短(12和13 d);T2、T3、T4叶片转色较晚,但T2最佳观赏期(14 d)显著低于T3和T4(25和25 d) (P<0.05)。

-

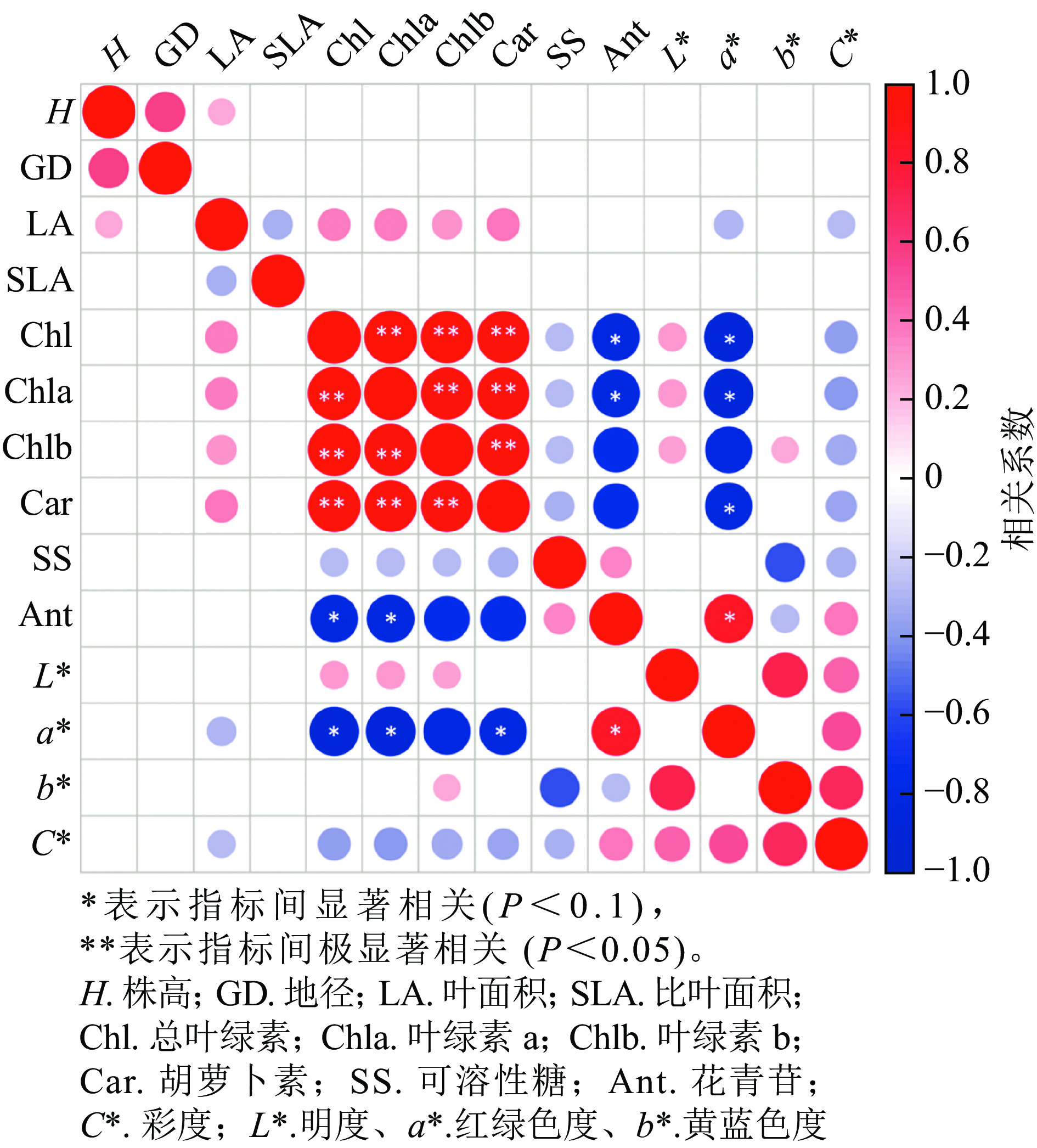

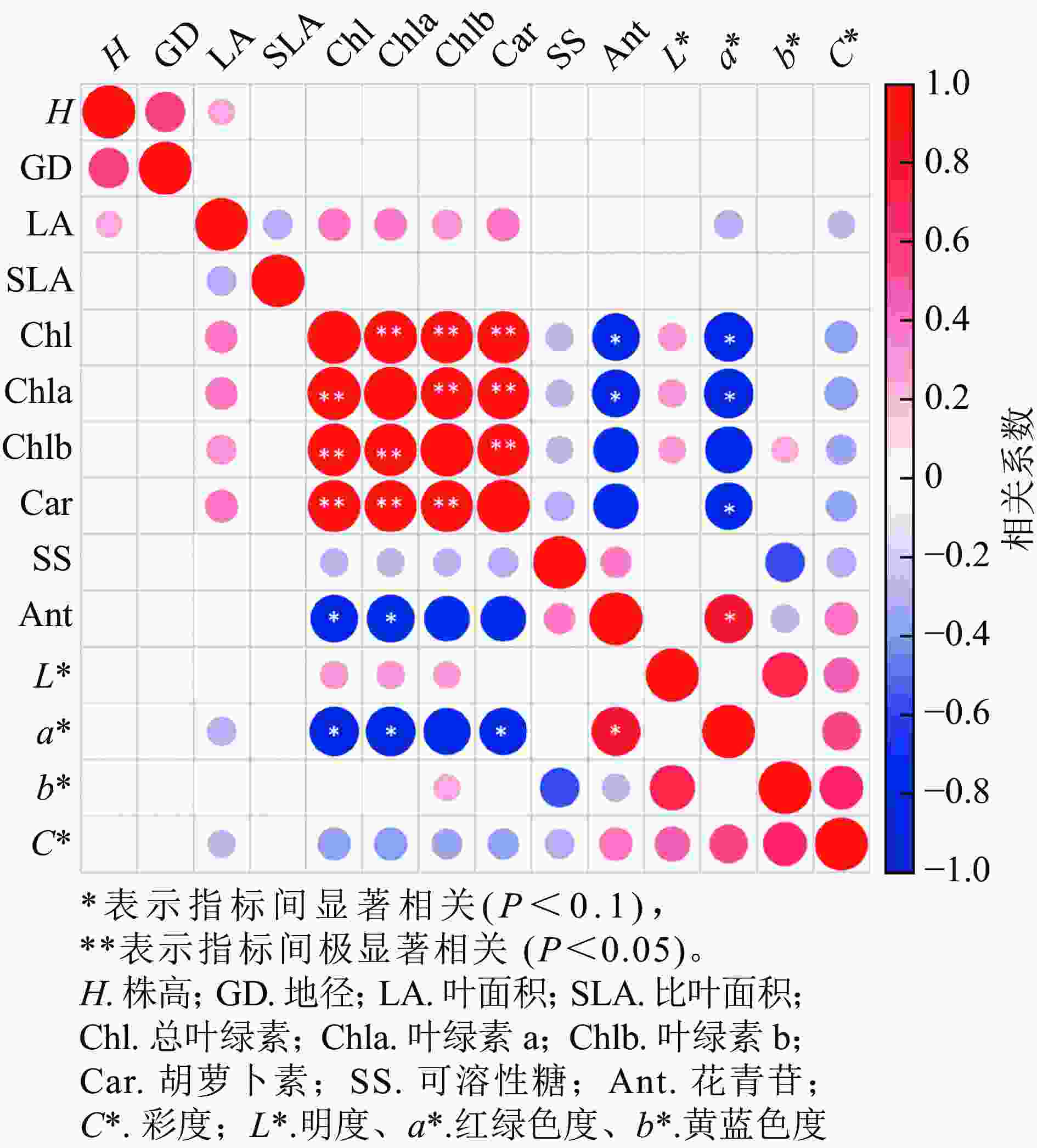

从各指标的相关性分析可知(图7),株高与地径、叶面积呈正相关,叶面积与叶绿素a、叶绿素b和类胡萝卜素呈正相关,与a*、C*呈负相关;叶绿素a与叶绿素b和类胡萝卜素呈显著正相关(P<0.05),与花色苷和a*呈显著负相关(P<0.05);花色苷与叶绿素a、叶绿素b和类胡萝卜素呈显著负相关(P<0.1),与a*呈显著正相关(P<0.1),和C*呈负相关;L*与叶绿素a、叶绿素b和C*呈正相关,与b*显著正相关(P<0.05)。

-

氮是植物生长发育的必需营养元素之一,不同的施氮量会影响植物生物量的积累[24]。KOCH等[25]发现施氮可以增加马铃薯Solanum tuberosum生长期的叶面积和叶片数量,提高对辐射和光子的拦截率,并对光合作用效率产生积极影响,促进马铃薯块茎膨大。适当施氮还有助于提高植株叶绿素含量、酶含量和酶活性[26−27],NASAR等[28]研究发现施氮能有效提高玉米Zea mays的株高和叶绿素含量,促进叶片光合作用,达到增产的目的;陈克玲等[29]研究发现适当施氮能显著提高烟草Nicotiana tabacum叶片的叶绿素含量以及蔗糖磷酸合成酶、蔗糖合成酶、谷氨酸合成酶的活性。在本研究中,施氮显著促进美国红枫生长,提高了美国红枫株高、地径和叶面积,使叶片接收更多光能辐射,同时也增加了美国红枫叶片的光合色素含量,有利于美国红枫叶片营养物质的积累。

叶片衰老是受遗传和环境因素共同控制的过程,而叶绿素的分解是叶片衰老最重要的标志[30]。WANG等[31]研究发现:添加养分能显著延缓落叶松松针的秋季衰老,成熟叶片氮浓度与叶片衰老时间之间呈正相关关系;较高的营养物质(如氮和磷)环境会使叶绿素降解较慢,延迟叶片衰老[17, 32]。在本研究中,施氮显著延缓了美国红枫叶片叶绿素的分解,在200 g·株−1施氮处理下叶绿素质量分数最高且叶绿素降解较慢,延长了叶片营养生长过程,推迟了叶片衰老;叶片可溶性糖增加也往往伴随着叶片衰老,又可以作为底物参与花青素的合成,并为花青素合成过程提供能量[33],本研究中对照的可溶性糖质量分数上升最早,但可溶性糖质量分数却不高,而200 g·株−1施氮处理在Ⅳ期大幅提升可溶性糖储备,支撑花青素的合成。目前定义植物开始衰老的时间没有统一标准,但总体基于叶片衰老过程中发生的3个过程:叶片营养物质再分配,总叶绿素降解和叶片着色[22]。通过连续测量不同时期的SPAD值,以及观察叶片着色情况,能一定程度反映植物的叶片衰老过程[34−35]。本研究各处理SPAD值与施氮量呈正相关,对照的SPAD值最小,下降时间早,叶片过早转色且提早落叶;而在200 g·株−1施氮处理下SPAD值一直保持较高水平,SPAD值下降时间较晚,叶片最晚开始转色,叶片转色时间相比对照推迟了20 d;说明在西南低海拔地区,施氮可以推迟美国红枫叶片衰老,延缓叶片的转色时间,为后续与低温相遇创造条件。

叶片转色主要是由高温或低温和干旱引起的,其中温度比干旱对叶片转色方面的影响更大[36]。较高的生长季气温和较低的秋季最低气温会诱导叶片着色日期提前[37]。陆秀君等[38]发现合适的氮磷钾配比能延长美国红枫幼苗观赏期;李林柯[39]发现适当的水肥耦合处理既能促进‘红冠’生长,又可以提高叶片呈色质量,其中养分对呈色和观赏期的贡献率大于水分。本研究结果表明:在西南低海拔地区,夏季的高温和秋季持续维持20 ℃以上的气温会导致美国红枫叶片提前衰老转色,缩短叶片观赏期,通过适当施氮可以延长叶片营养生长期,推迟美国红枫的叶片衰老过程,延缓叶片转色。花青素是叶片呈红呈彩的关键,而低温是影响花青素合成的主要因素[40],低温能通过诱导转录因子SlAREB1的表达,影响脱落酸含量,进一步调控花青苷相关合成基因的表达[41]。在西南低海拔地区,通过施氮推迟美国红枫叶片衰老过程,使观赏期与冬季的低温条件相遇,促进了叶片花青苷的合成,且施氮显著增加了叶片中可溶性糖质量分数,为花青苷合成代谢提供了底物和能量,进一步增加了美国红枫叶片花青苷含量,显著提高了美国红枫的叶色质量并延迟了最佳观赏期。

-

适量施氮能显著提高美国红枫株高、地径和叶面积,增强光能捕获能力,并增加叶片叶绿素和类胡萝卜素质量分数,进而促进光合作用及营养物质积累;同时适量施氮可延缓叶绿素降解,推迟叶片衰老,延长营养生长期。本研究证实:在西南低海拔地区,秋季的较高温度易导致叶片提前衰老和转色,而适当施氮(150~200 g·株−1)能通过延缓衰老进程,使其与低温条件相遇,促进叶片花青素的合成,有效提高美国红枫叶片可溶性糖质量分数和花青苷含量,显著提升美国红枫在西南低海拔地区的生长性能和秋季叶色观赏价值。

Effects of nitrogen application on growth and leaf coloration of Acer rubrum

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250430

- Received Date: 2025-08-12

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-10-03

- Publish Date: 2025-10-20

-

Key words:

- Acer rubrum /

- anthocyanins /

- senescence /

- change color /

- best viewing period

Abstract:

| Citation: | LIU Sheng, DUAN Xiaoxuan, KAN Lumei, et al. Effects of nitrogen application on growth and leaf coloration of Acer rubrum[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2025, 42(5): 1068−1077 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250430 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: