-

土壤盐碱化是全球范围内非常严峻的环境问题,目前已有超过13.81亿hm2的土地受到过量盐分的影响[1]。过高的盐分会在植物体内引发渗透胁迫、离子胁迫和氧化胁迫,导致水分吸收受阻,离子平衡及细胞稳态破坏,从而抑制植物的生长与发育,甚至造成植株死亡[2−3]。植物通常通过渗透调节、离子稳态调节和活性氧清除等途径应对盐胁迫[2−3],而植物激素在这些过程中发挥着重要调控作用[4−5]。已有研究表明:褪黑素(melatonin)[6]、茉莉酸甲酯(methyl jasmonate,MeJA)[7]、水杨酸(salicylic acid,SA)[8]、细胞分裂素(cytokinin,CK)[9]、乙烯(ethylene)[10]以及脱落酸(abscisic acid,ABA)[11]等多种植物激素参与盐胁迫的响应。

脱落酸被认为是植物应对逆境,尤其是盐胁迫的核心信号因子[11]。外源施加脱落酸可有效缓解盐胁迫对植物生长的抑制[12];施加脱落酸合成抑制剂钨酸钠(Na2WO4),则会削弱植物的渗透调节能力,阻碍气孔关闭并加剧活性氧积累,最终导致植株生长受抑[13−16]。在盐胁迫条件下,植物体内脱落酸会迅速升高,从而启动一系列防御机制。首先,脱落酸能够被受体PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE/PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE-LIKE(PYR/PYL)感知,受体结合脱落酸后可以抑制蛋白磷酸酶(protein phosphatase 2C,PP2C)的活性,进而解除对Ⅲ类SnRK2蛋白激酶的抑制,并使其下游靶蛋白发生磷酸化[17]。活化的SnRK2激酶进一步调控多种生理过程,包括离子转运和气孔关闭等[18],并通过调控多种转录因子介导渗透物质的生物合成[19−22]。

芙蓉菊Crossostephium chinense是菊花Chrysanthemum × morifolium的近缘属物种,能够在700 mmol·L−1 氯化钠(NaCl)的胁迫条件下维持正常的形态和生理功能。甘菊C. lavandulifolium是菊花同属植物,在500 mmol·L−1 氯化钠胁迫下即整株死亡,对盐敏感,耐盐性差[23]。已有研究表明:将芙蓉菊作为母本,甘菊为父本进行属间远缘杂交能够获得杂交后代[24]。也有研究对父母本甘菊、芙蓉菊与杂交后代统一进行了耐盐评价,发现后代耐盐性介于两亲本之间,其中FG26后代相对较为耐盐[23]。这表明芙蓉菊可通过属间杂交将耐盐等优良性状导入栽培菊花,获得杂交后代。尽管前期研究表明芙蓉菊具有强耐盐性,但其耐盐相关的及与后代遗传有关的生理及分子机制,特别是脱落酸在芙蓉菊盐胁迫过程中所起的作用和影响尚不明确。基于此,本研究以耐盐种质芙蓉菊,盐敏感种质甘菊及较耐盐的杂交后代FG26为研究材料,系统评估盐胁迫下植株内源脱落酸的动态变化;分析外源施加脱落酸及脱落酸合成抑制剂钨酸钠处理对耐盐性相关关键生理指标的影响,包括脯氨酸(proline,Pro)、超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase,SOD)和丙二醛(malondialdehyde,MDA),并结合转录组数据[25],解析脱落酸在芙蓉菊及杂交后代盐胁迫适应过程中的生理分子层面的调控机制,以期为耐盐菊花新品种的创制提供理论依据和基因资源。

-

选用耐盐型芙蓉菊、盐敏感型甘菊及以芙蓉菊作为母本、甘菊为父本获得的较耐盐杂交后代FG26为研究材料[23−24]。试验材料种植于国家花卉工程研究中心研发温室。3种材料的扦插苗在蛭石∶珍珠岩为1∶1(体积比)的基质中生根,随后移栽至草炭∶珍珠岩∶松针土为6∶3∶1(体积比)的基质中,在人工气候室中培养1.5个月。培养条件为光周期12 h (光照)/12 h (黑暗)、温度25 ℃和相对湿度60%。

-

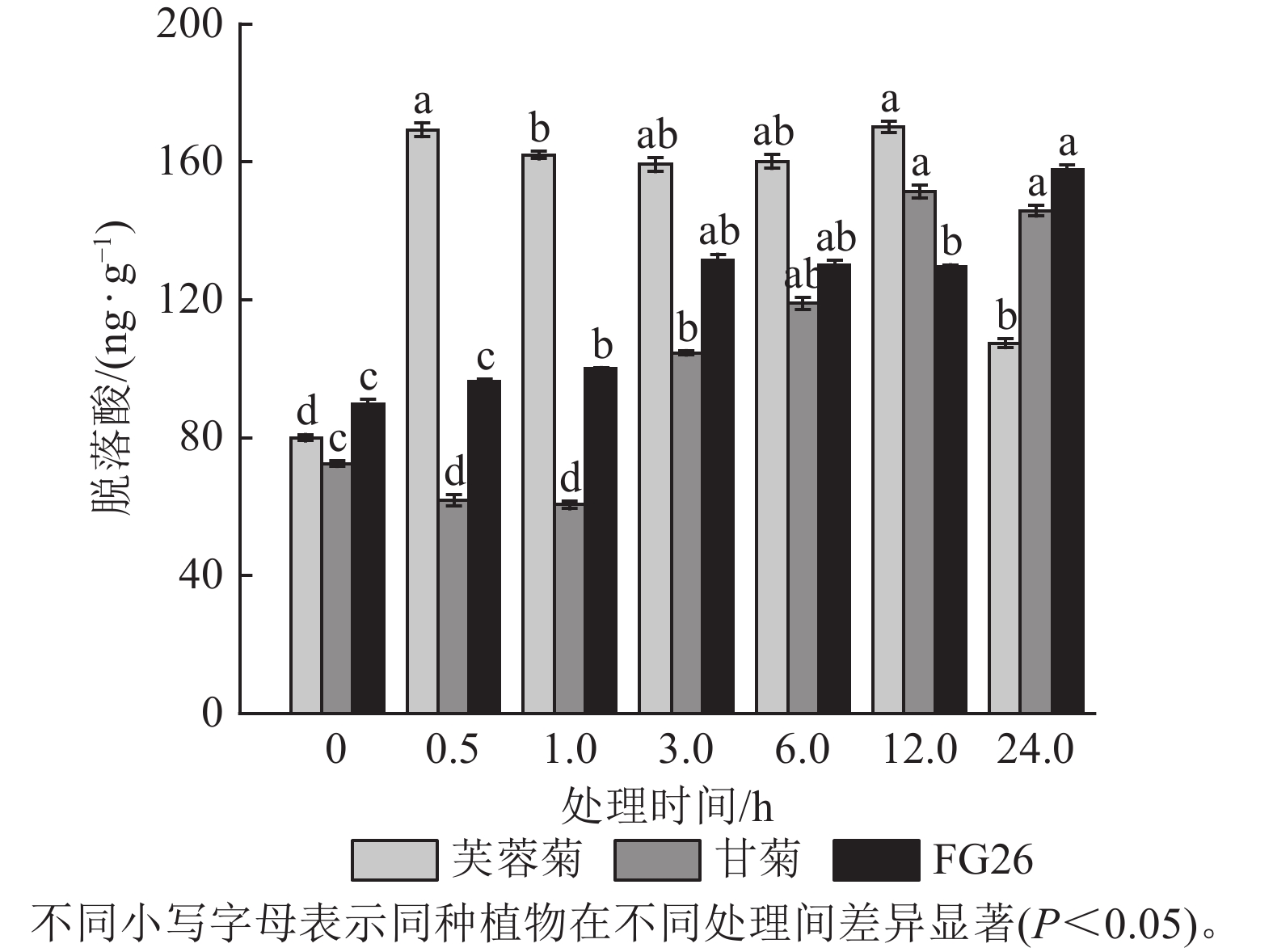

选择生长状态良好且一致的植株进行试验,每个处理设置3个生物学重复。参考盐胁迫转录组的研究[25],采用700 mmol·L−1氯化钠溶液处理植株,并分别于处理0、0.5、1.0、3.0、6.0、12.0和24.0 h在中段叶位采集叶片样品0.5 g。样品迅速用铝箔纸包裹,经液氮速冻后转移至−80 ℃超低温冰箱保存,用于内源激素质量分数测定,所用样品均为鲜质量。脱落酸质量分数的测定采用酶联免疫吸附法(ELISA)[26]。

-

为筛选出适宜的处理浓度,预试验以清水处理为对照,将3种材料的扦插苗分别用不同浓度的氯化钠(0、100、300 mmol·L−1)结合不同浓度的脱落酸(0、100、150、200 μmol·L−1)或钨酸钠(0、1、2 mmol·L−1)处理7 d。结果表明,300 mmol·L−1 氯化钠结合200 μmol·L−1 脱落酸或1 mmol·L−1钨酸钠处理,生理指标变化最显著(P<0.05),3种材料间差异最大,且植株均未死亡。因此,正式试验选用300 mmol·L−1 氯化钠、200 μmol·L−1 脱落酸及1 mmol·L−1钨酸钠作为处理浓度。

选择生长状态良好且一致的植株进行试验,每个处理设置5个生物学重复,胁迫时间为7 d。以0 mmol·L−1 氯化钠处理并施加清水为对照组(ck),以300 mmol·L−1 氯化钠溶液处理并施加清水(T1)、300 mmol·L−1 氯化钠溶液处理并施加200 μmol·L−1 脱落酸(T2),以及300 mmol·L−1 氯化钠溶液处理并施加1 mmol·L−1 钨酸钠溶液(T3)为试验组。试验在人工气候室中进行,培养条件为光周期12 h (光照)/12 h (黑暗)、温度25 ℃和相对湿度60%。处理结束后在中段叶位采集叶片样品0.5 g,经铝箔纸包裹、液氮速冻后,保存于−80 ℃冰箱,用于内源脱落酸、脯氨酸、超氧化物歧化酶活性及丙二醛测定。所用样品均为鲜质量。

-

脯氨酸采用可见分光光度法测定[27],超氧化物歧化酶活性采用WST-1法测定[28],丙二醛采用硫代巴比妥酸法(TBA)测定[29]。所用试剂盒均购自南京建成生物科技有限公司。

-

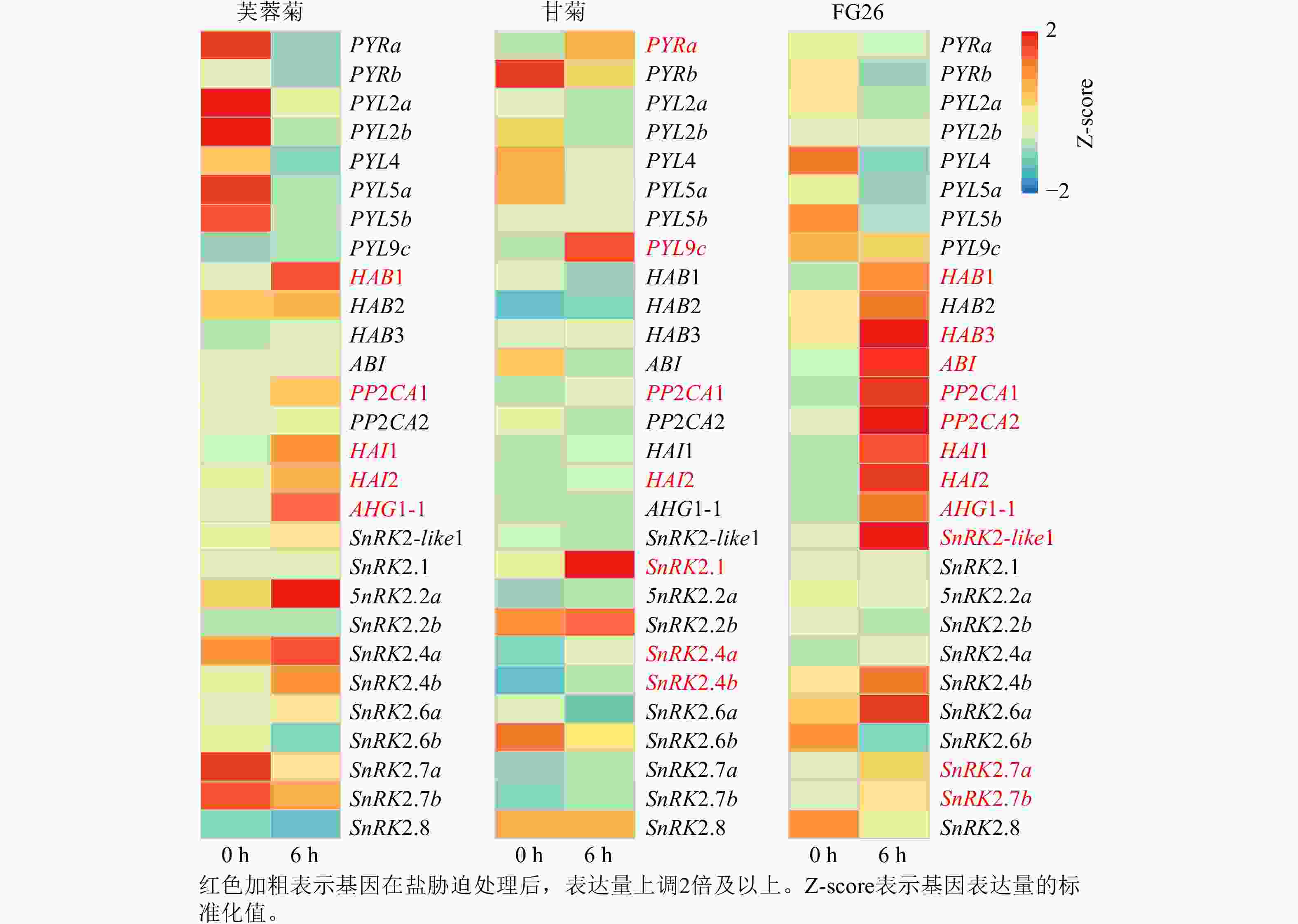

根据已发表转录组数据[25],提取芙蓉菊中与盐胁迫响应有关的PYRs/PYLs、PP2Cs和SnRK2s基因的TPM(transcripts per million)值,并利用TBtools绘制基因表达热图[30]。

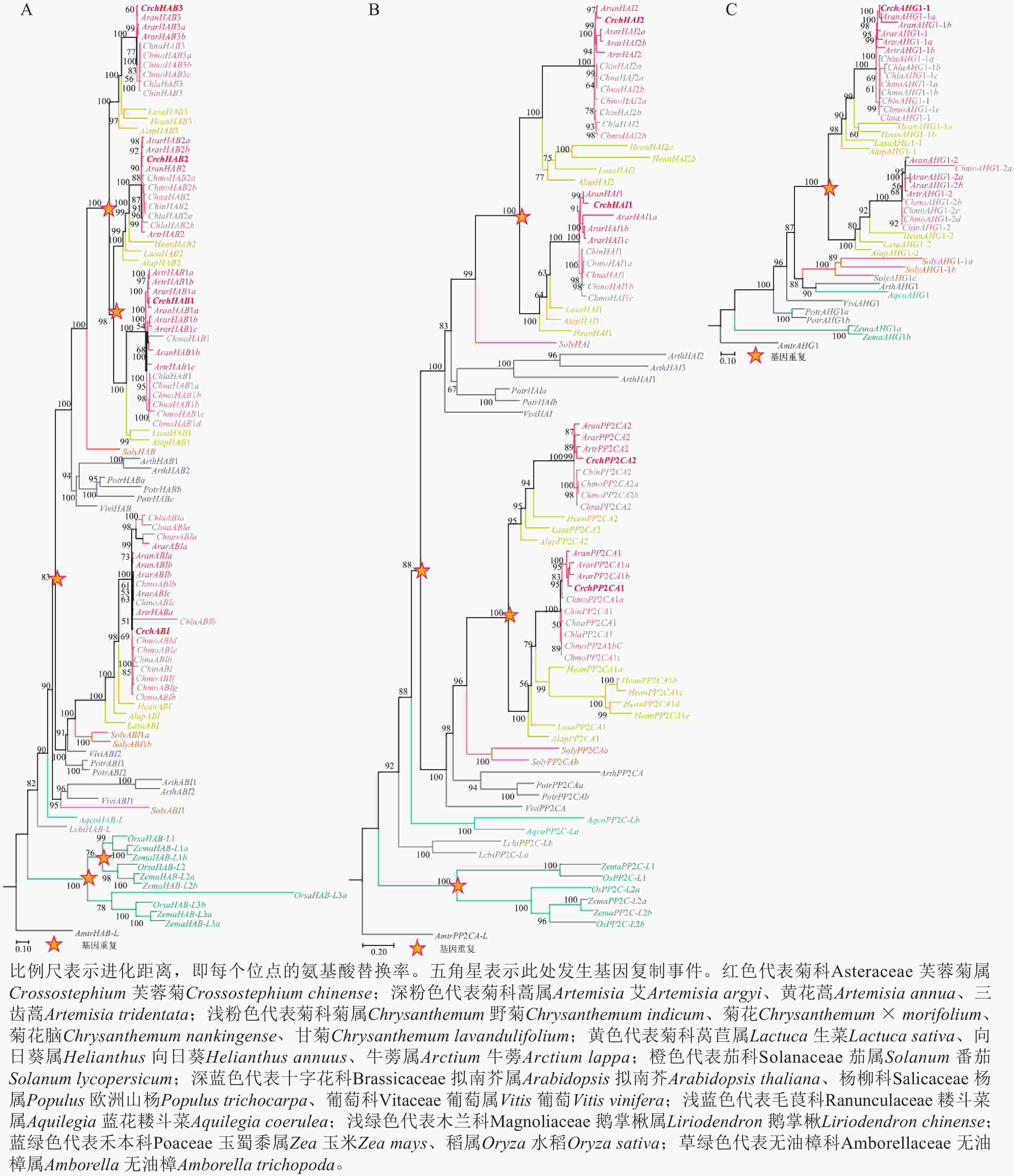

以拟南芥Arabidopsis thaliana脱落酸信号通路中盐胁迫响应有关的PYRs/PYLs、PP2Cs和SnRK2s基因的蛋白质序列为查询序列[2−3],使用 BLASTP v2.5.0+在芙蓉菊转录组及其他18个被子植物的基因组中搜索对应的同源基因,E的阈值设为1.0×10−5[31]。为进行系统发育分析,各基因的氨基酸序列使用 MAFFT v7.505 进行比对[32],并通过 PAL2NAL v14 生成对应的基于密码子的核苷酸比对[33]。随后使用 IQ-TREE 2.1.4-beta 构建最大似然系统发育树,参数设置为“-bb

1000 -nt AUTO”[34],并利用MEGA11进行可视化[35]。本研究用到的转录组和基因组数据均下载于已发表的研究论文(表1)。科名 种名 缩写 参考文献 科名 种名 缩写 参考文献 菊科 Asteraceae 芙蓉菊Crossostephium chinense Crch [25] 茄科 Solanaceae 番茄Solanum lycopersicum Soly [46] 野菊Chrysanthemum indicum Chin [36] 十字花科 Brassicaceae 拟南芥Arabidopsis thaliana Arth [47] 菊花Chrysanthemum × morifolium Chmo [37] 杨柳科 Salicaceae 欧洲山杨Populus trichocarpa Potr [48] 菊花脑Chrysanthemum nankingense Chna [38] 葡萄科 Vitaceae 葡萄Vitis vinifera Vivi [49] 甘菊Chrysanthemum lavandulifolium Chla [39] 毛茛科 Ranunculaceae 蓝花耧斗菜Aquilegia coerulea Aqco [50] 生菜Lactuca sativa Lasa [40] 禾本科 Poaceae 玉米Zea mays Zema [51] 向日葵Helianthus annuus Hean [41] 水稻Oryza sativa Orsa [52] 牛蒡Arctium lappa Alap [42] 木兰科Magnoliaceae 鹅掌楸Liriodendron chinense Lich [53] 艾Artemisia argyi Arar [43] 无油樟科Amborellaceae 无油樟Amborella trichopoda Amtr [54] 黄花蒿Artemisia annua Aran [44] 三齿蒿Artemisia tridentata Artr [45] Table 1. Genomic and transcriptomic data used for phylogenetic analyses

-

采用Excel 2021进行数据统计和处理,用SPSS 26软件进行单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA),采用Duncan’s多重比较检验(P<0.05)分析不同处理间的差异显著性。

-

盐胁迫会影响植物代谢,进而对植物内源激素产生影响,所以内源激素水平的变化可以反映植物对盐胁迫的响应。由图1可知:盐胁迫显著改变了3种植物叶片的内源脱落酸质量分数(P<0.05)。芙蓉菊的脱落酸质量分数在盐处理后0.5 h即快速响应,显著升高至169.37 ng·g−1(P<0.05),较处理0 h增加 111.71%。随后较长时间内(1~12 h),脱落酸质量分数持续保持较高的水平,直至24 h显著下降(P<0.05),恢复至接近处理前的水平。甘菊的脱落酸质量分数呈现先下降后上升再下降的趋势,响应过程较为缓慢,在12 h才达到峰值(151.40 ng·g−1)。后代FG26的脱落酸质量分数则一直呈现上升趋势,在24 h时仍呈现出上升趋势(157.78 ng·g−1)。这些结果表明:脱落酸在3种植物盐胁迫响应过程中均发挥作用,但芙蓉菊中脱落酸对盐胁迫的响应速度更加迅速,在1~12 h内都保持着较高质量分数。FG26的脱落酸一直保持着上升趋势,而甘菊的脱落酸调控可能存在延迟,响应速度较慢,且在24 h内甘菊与FG26的脱落酸质量分数都低于芙蓉菊在0.5 h的脱落酸质量分数,甘菊的峰值质量分数也小于FG26的最终质量分数。

-

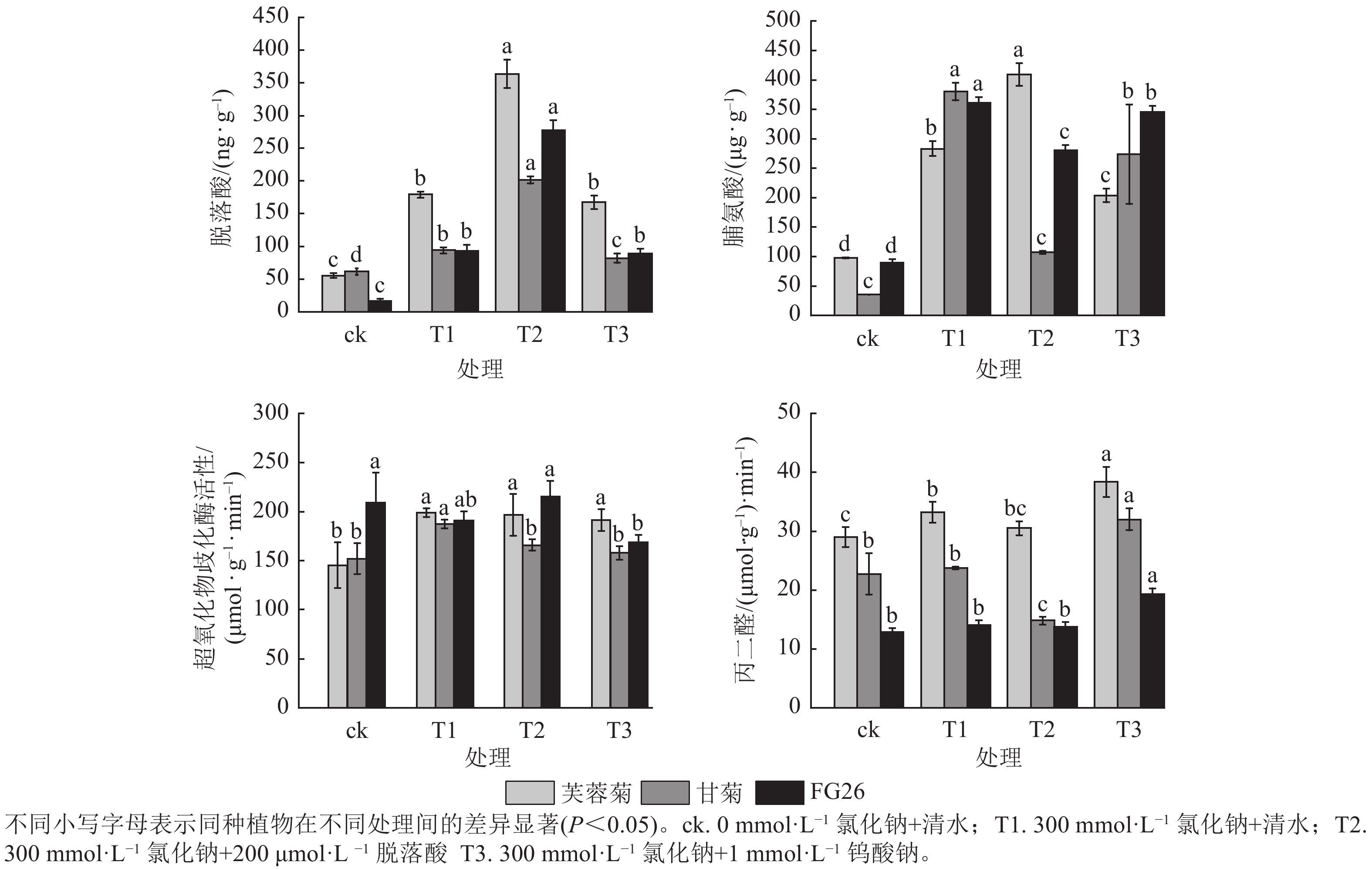

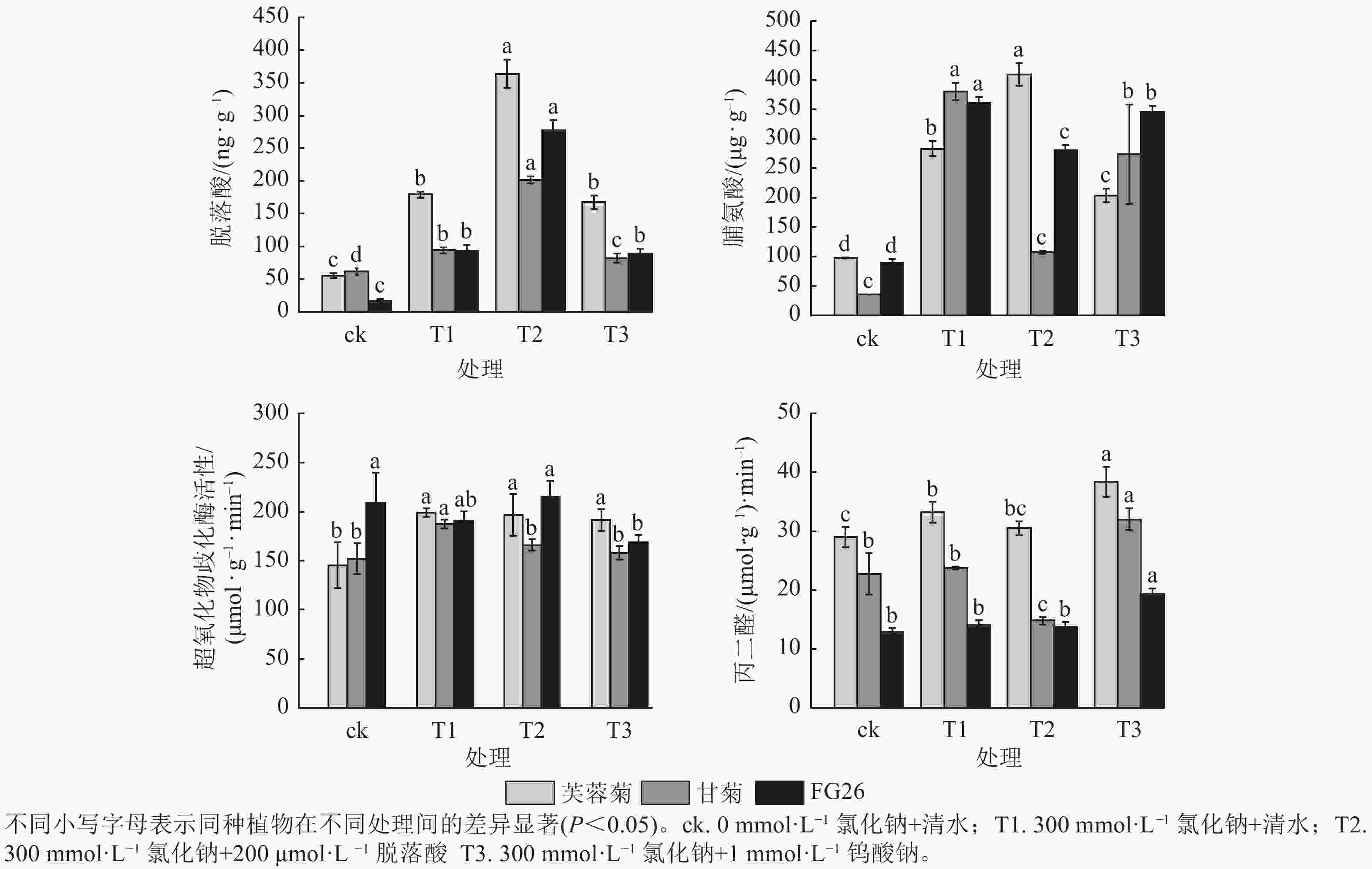

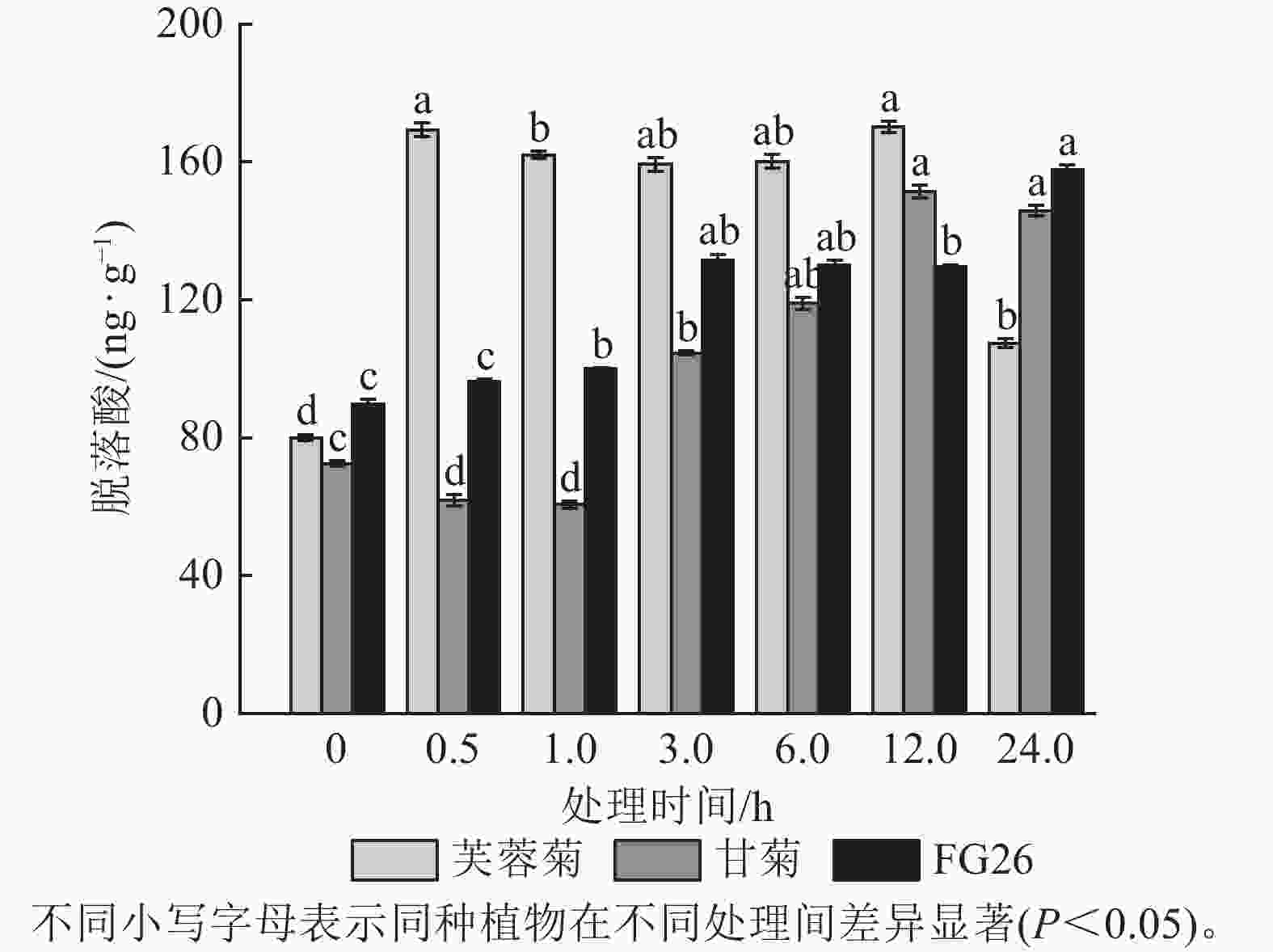

由图2可知:T1处理显著提升3种植物脱落酸质量分数(P<0.05),较ck分别增加3.23、1.53及5.61倍。T2处理进一步提高了三者脱落酸质量分数,较T1分别增加2.03、2.14及2.99倍,且T1、T2处理中芙蓉菊的脱落酸质量分数均最高,FG26的脱落酸上升倍数最高。相反,在T3处理时,降低了脱落酸质量分数,芙蓉菊脱落酸质量分数较T1下降了6.31%,甘菊下降幅度最大达12.72%,FG26下降幅度最小达4.00%。

Figure 2. Effects of exogenous ABA and Na2WO4 on physiological indicators of Crossostephium chinense, Chysanthemum lavandulifolium and their hybrid FG26 under salt-stress condition

T1处理使3种植物脯氨酸质量分数显著上升(P<0.05),较ck分别增加2.90、10.69及4.03倍,三者脯氨酸质量分数及上升倍数和耐盐力强弱排序相反,盐敏感型甘菊的脯氨酸质量分数上升倍数最高,可能是因为甘菊作为盐敏感物种,遭受的胁迫更严重,促使渗透调节物质被动积累,但其细胞结构或保护系统无法有效利用这些物质,最终仍死亡。T2处理促进芙蓉菊中脯氨酸质量分数较盐处理组上调44.42%,而在甘菊和FG26中,脯氨酸质量分数较T1分别降低71.74%和22.27%,可能暗示着脯氨酸代谢途径对高浓度脱落酸的响应存在物种特异性。在T3处理中,3种植物的脯氨酸质量分数较T1分别下降了28.00%、28.00%及4.45%,其中FG26的下降幅度远小于芙蓉菊与甘菊,进一步证明了脱落酸在渗透调节中的积极作用。

T1处理芙蓉菊的超氧化物歧化酶活性最高,FG26次之,甘菊最低;与ck相比,芙蓉菊、甘菊中超氧化物歧化酶活性显著升高(P<0.05),分别增加1.37和1.23倍,而FG26中变化不显著(P<0.05)。在T2和T3处理中,芙蓉菊和FG26较T1变化均不显著,可能由于其活性氧清除系统在盐胁迫下较为稳定,受到干扰较小;甘菊的超氧化物歧化酶活性较T1分别下降11.45%与15.72%,说明其抗氧化系统较为脆弱,易受胁迫扰动。

T1处理导致3种植物丙二醛质量摩尔浓度上升,较ck分别增加14.62%、4.58%和9.47%,芙蓉菊上升幅度最大,但其基础丙二醛质量摩尔浓度较甘菊高,耐盐性却最强,推测其较甘菊来说具备更强膜修复与抗氧化能力,或细胞膜结构存在差异。在T2处理中,甘菊较T1处理丙二醛质量摩尔浓度显著下降37.63% (P<0.05),而芙蓉菊和FG26变化不显著,可能暗示着脱落酸能有效缓解盐胁迫对盐敏感物种的膜损伤,对耐盐性强的物种作用不显著。在T3处理中,3种植物较T1组丙二醛质量摩尔浓度均有显著上调(P<0.05),分别上调了15.43%、34.72%及36.95%,进一步验证内源脱落酸在维持细胞膜稳定性中的关键作用。

-

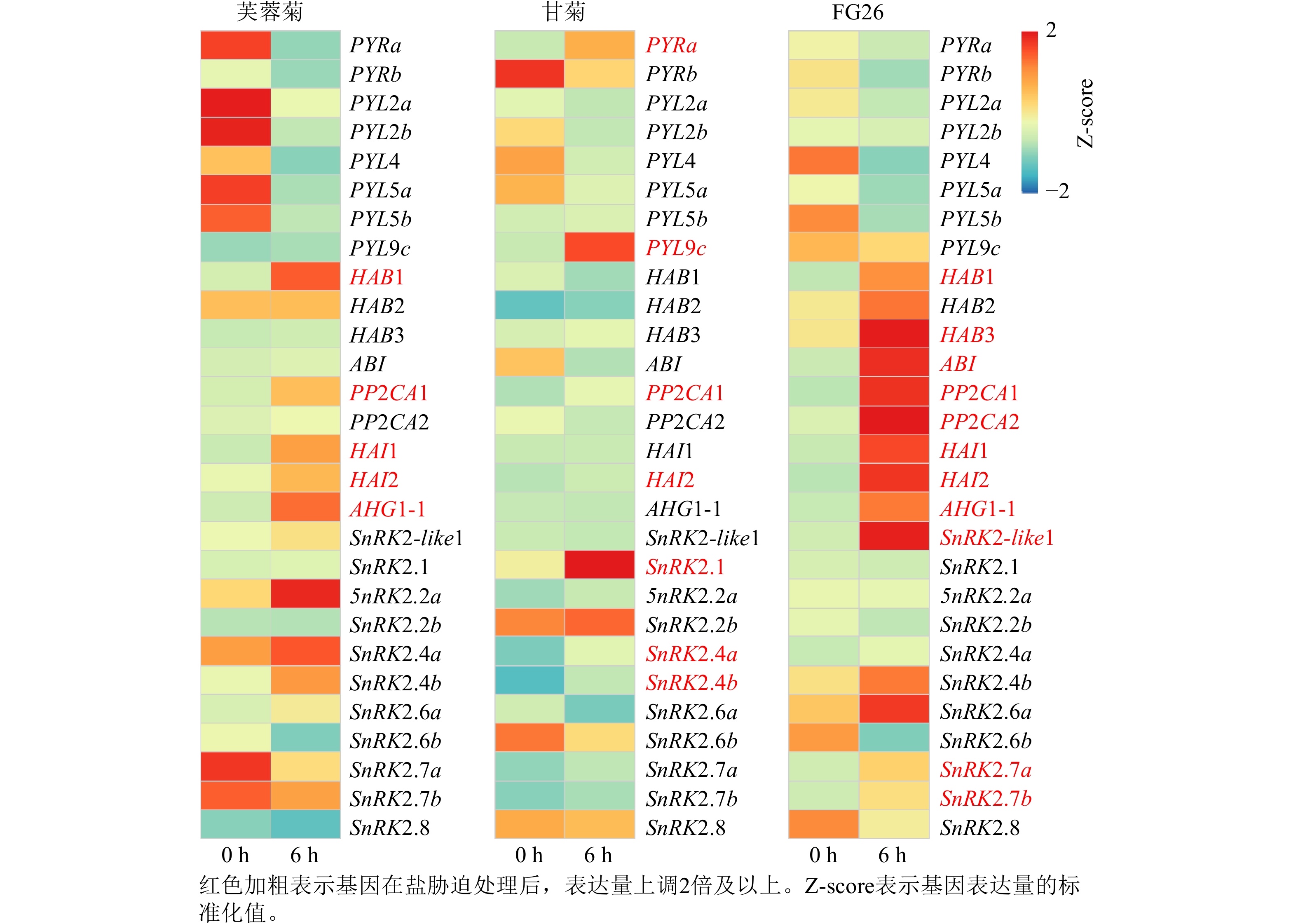

基于前期已发表的芙蓉菊转录组数据[25],共鉴定到脱落酸信号通路中响应盐胁迫关键基因28个,其中包括8个PYRs/PYLs基因,9个PP2Cs基因和11个Ⅲ类SnRK2s基因(图3)。在上述28个候选基因中,芙蓉菊中有5个PP2Cs基因在盐胁迫处理6 h后表达显著上调。值得注意的是,PP2CA1和HAI2在盐胁迫处理6 h后3种植物中的表达水平均显著提高,暗示它们在盐胁迫响应中的调控作用可能具有保守性。相反,另外3个基因(HAB1、HAI1和AHG1-1)则仅在盐胁迫处理6 h后的芙蓉菊和FG26中表达上调,表明PP2C类基因,尤其是HAB1、HAI1和AHG1-1,可能对芙蓉菊超强耐盐特性的获得具有重要作用,并且能够通过杂交遗传给后代,增强后代的耐盐性。

-

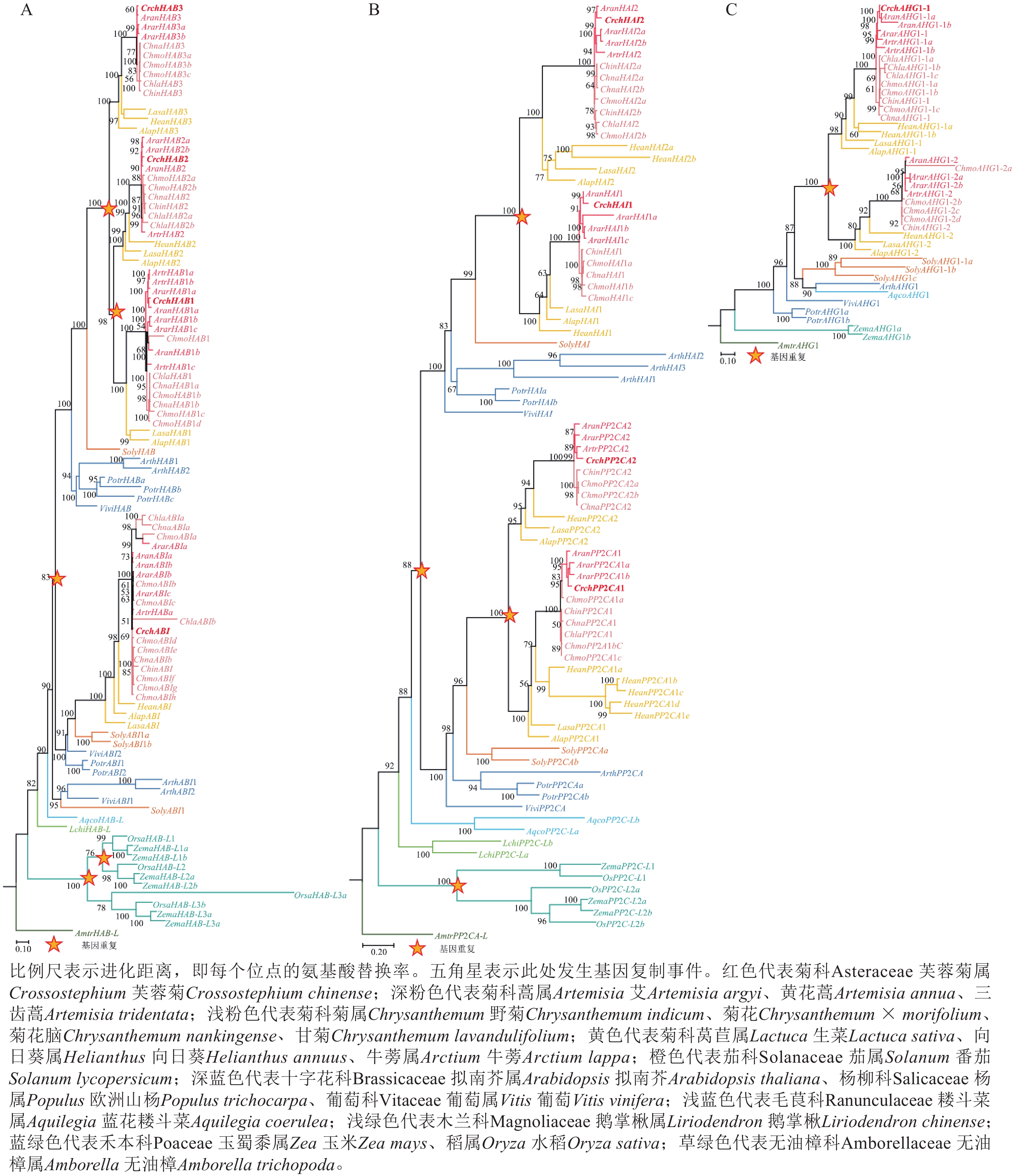

对芙蓉菊耐盐关键候选基因PP2C家族基因的进化历史进行了研究。由图4A可知:HAB类基因在芙蓉菊的进化过程中发生了3次基因重复,形成了CrchHAB1、CrchHAB2、CrchHAB3和CrchABI等4个拷贝。其中1次重复事件发生于核心真双子叶最近共同祖先中,其余2次发生于菊科Asteraceae植物的最近共同祖先中。类似地,由图4B可知:PP2CA类基因同样经历了3次重复事件。其中1次重复事件发生在核心真双子叶最近共同祖先中,形成PP2CA和HAI等2个分支。随后,这2个分支分别在菊科最近共同祖先中各发生1次重复,形成CrchPP2CA1、CrchPP2CA2、CrchHAI1和CrchHAI2等4个拷贝。由图4C可知:AHG1基因在菊科最近共同祖先中发生过1次重复,但在芙蓉菊中丢失了其中1个拷贝,仅保留CrchAHG1-1。上述结果表明:芙蓉菊PP2C家族基因经历了与菊科多数植物相似的基因重复事件,暗示基因重复后的表达分化可能在芙蓉菊耐盐特性形成中发挥了重要作用。

-

植物激素在植物应对非生物胁迫的过程中发挥着关键作用[55]。本研究结果表明:盐胁迫导致芙蓉菊、甘菊及其杂交后代FG26的内源脱落酸质量分数均显著升高。这与盐胁迫下燕麦Avena sativa[56]、向日葵Helianthus annuus[57]的脱落酸变化趋势相似,表明脱落酸在盐胁迫响应中具有重要作用。芙蓉菊表现出更快速强烈的脱落酸响应,其峰值最高,FG26次之,甘菊最低。这可能与3种植物的耐盐性差异有关。

T2处理提高了3种植物的内源脱落酸质量分数,其中芙蓉菊内源脱落酸质量分数最高,FG26的上升倍数最高。这与盐胁迫下外源脱落酸对楸树Catalpa bungei内源脱落酸质量分数的影响结果相符[58]。T3处理下,甘菊的脱落酸质量分数下降幅度最大,其次是FG26,芙蓉菊最小。表明芙蓉菊具有更强的脱落酸合成及代谢调控能力。渗透调节方面,T1处理的甘菊脯氨酸质量分数和增幅变化表明:在盐胁迫下可能是因为甘菊作为盐敏感物种,遭受的胁迫更严重,促使渗透调节物质被动积累,但其细胞结构或保护系统无法有效利用这些物质,最终仍死亡。T2处理可显著提高芙蓉菊的脯氨酸质量分数,这与刺槐Robinia pseudoacacia[59]、鹰嘴紫云英Astragalus cicer[60]在盐胁迫时外施脱落酸的脯氨酸变化一致。甘菊与FG26的脯氨酸质量分数下降,可能暗示着脯氨酸代谢途径对高质量分数脱落酸的响应存在物种特异性。

T1处理下芙蓉菊和甘菊的超氧化物歧化酶活性上升。这与望春玉兰Magnolia biondii[61],八棱海棠Malus × robusta[62]在盐胁迫时外施脱落酸的超氧化物歧化酶的变化一致。T2及T3处理组对芙蓉菊和FG26的超氧化物歧化酶质量分数均无显著影响,表明其活性氧清除系统具备较强的稳定性。甘菊的超氧化物歧化酶质量分数易受干扰,说明其抗氧化系统较为脆弱。T1处理导致3种植物的丙二醛均有上升,这与望春玉兰[61]、红豆草Onobrychis cyri[63]在盐胁迫下的丙二醛质量摩尔浓度变化一致。芙蓉菊丙二醛质量摩尔浓度相对增幅较大,表明芙蓉菊可能具备更强的细胞膜修复能力或抗氧化能力。T2处理能显著降低甘菊的丙二醛质量摩尔浓度,这与银边吊兰Chlorophyt comosum var. variegatum[64]在盐胁迫下外施脱落酸的丙二醛变化一致。但T2处理对芙蓉菊和FG26的丙二醛影响不显著,说明脱落酸可能对盐敏感物种的丙二醛作用更强。T3处理则显著提高3种植物丙二醛质量摩尔浓度,反面证实了内源脱落酸在维持细胞膜稳定性中的作用。

在分子水平上,基于转录组数据[25],芙蓉菊脱落酸信号通路关键基因中PP2Cs家族基因在盐胁迫下表现出显著差异表达。PP2CA1和HAI2在3种植物中均呈显著上调,显示其盐胁迫响应的保守性;而HAB1、HAI1和AHG1-1则仅在芙蓉菊及FG26中表达上调,表明它们可能是芙蓉菊强耐盐性形成及其向子代传递的关键分子基础。在拟南芥中过表达AtHAIs能提高植物抗逆性[65],也有研究证实AtHAB3参与脱落酸响应过程[66]。同时,已证实天女木兰Magnolia sieboldii中MsAHG1能改变脱落酸敏感性[67],并且EsHABs、EsHAIs、EsAHG1在耐盐植物盐芥Eutrema salsugineum中可以增强耐盐性[68]。系统发育分析表明:PP2Cs基因经历了与菊科多数植物类似的基因重复事件,重复后基因的表达分化也可能为芙蓉菊耐盐特性的形成提供了分子基础。这些发现与盐胁迫下芙蓉菊脱落酸的迅速响应及其他生理变化形成了生理与分子协同的耐盐机制。

-

盐胁迫下芙蓉菊、甘菊及其杂交后代FG26的内源脱落酸质量分数均显著升高,表明脱落酸在盐胁迫响应中发挥关键作用。脱落酸可调控耐盐性,但调控效应具有物种特异性,主要通过促进芙蓉菊渗透调节和减轻甘菊细胞损伤参与植物盐胁迫响应。芙蓉菊较强的耐盐性源于脱落酸的快速响应能力、脱落酸代谢稳定性以及高效的渗透调节与较稳定的抗氧化与膜保护系统。杂交后代FG26在多数生理指标上介于两亲本之间,但更倾向于耐盐亲本,表现出一定的杂交优势。通过转录组数据和系统发育分析,发现了仅在芙蓉菊及FG26中表达上调的PP2C类基因HAB1、HAI1和AHG1-1。它们可能在芙蓉菊超强耐盐性的形成中发挥核心作用,并且能够通过杂交遗传给后代。本研究不仅揭示了脱落酸在盐胁迫中的作用及在不同耐盐性菊科植物中的调控机制,还分析了芙蓉菊及其杂交后代响应盐胁迫的生理与分子层面上的变化,为耐盐菊花新品种创制提供了可参考的理论依据。

Physiological characteristics and molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance regulated by abscisic acid in Crossostephium chinense and its hybrid progeny

doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250469

- Received Date: 2025-08-30

- Accepted Date: 2025-09-27

- Rev Recd Date: 2025-09-26

- Publish Date: 2025-10-20

-

Key words:

- salt stress /

- Crossostephium chinense /

- ABA /

- PP2C gene family

Abstract:

| Citation: | LIU Chang, LU Yufan, JIANG Yan, et al. Physiological characteristics and molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance regulated by abscisic acid in Crossostephium chinense and its hybrid progeny[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2025, 42(5): 1025−1036 doi: 10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20250469 |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: