-

桂花Osmanthus fragrans为木犀科Oleaceae园林观赏植物,是中国十大传统名花之一,自古享有“独占三秋压众芳”的美誉。其树姿优美,在园林中常用作行道树、孤植树;因香气浓郁,被列为中国重要的天然保健植物和特产经济香花植物,广泛用于食品添加剂及护肤品等产业。关于桂花茶、桂花(米)酒、桂花糕等鲜花采收加工产业已成熟,近年来新兴的桂花香水、乳液、香熏和精油等高档化妆品也逐渐打开市场[1−3]。然而,由于桂花花期较短,最佳观赏期和采收期仅2~3 d,极大地限制了其观赏价值与经济价值[4−5]。在目前记载的160多个桂花品种中,大部分由于雌蕊败育不结实,表现为开花后期脱落型;另一类为结实型桂花品种,开花后期花瓣表现为萎蔫,在树体不脱落[6]。前期研究发现:在不结实桂花品种‘柳叶金桂’O. fragrans ‘Liuye Jingui’的衰老过程中,当脱落期花瓣出现明显可见的衰老特征时,花瓣中DNA断裂迅速增加,衰老后期花瓣中出现染色质凝结等典型的细胞程序性死亡(PCD)现象[4, 7]。然而,对于结实型桂花衰老过程中的PCD特征还不清楚。因此,本研究以结实型桂花品种‘潢川金桂’O. fragrans ‘Huangchuan Jingui’为试材,探索结实型桂花花瓣衰老过程中PCD特征,为桂花花瓣衰老机制提供理论支撑。

-

选取华中农业大学校园内40~50年生、健康、无病虫害、四周光照均匀的‘潢川金桂’植株,分别采收不同开花阶段的桂花花朵,收集花瓣后称量,保存在冰盒或者液氮中,立即带回实验室,进行指标的检测并存至−80 ℃超低温冰箱备用。

-

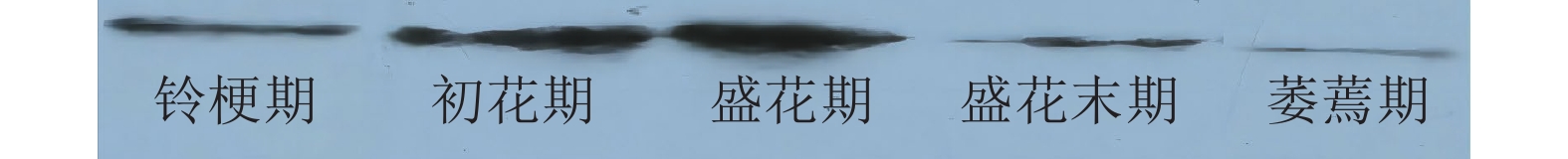

参考ZOU等[4]桂花开花级数的划分体系,将 ‘潢川金桂’开花级数划分为:①铃梗期(花苞期),花朵呈紧闭的花苞状,未展开;②初花期,花朵微张,呈半开放状态;③盛花期,花瓣完全展开,柱头产生黄色黏性物时进行授粉,花径达到最大;④盛花末期,花瓣略微开始失水,有的花瓣伴随褐斑出现;⑤萎蔫期,花朵失水萎焉并留在树体上,花瓣呈黄褐色,子房略膨大。

-

参考ZOU等[4]的方法测定ROS质量摩尔浓度(nmol·g−1),参考林植芳等[8]的方法测定过氧化氢质量摩尔浓度(nmol·g−1)。称取新鲜花瓣组织0.2 g,按材料与提取液1∶1的质量比加入4 ℃下预冷丙酮和少许石英砂研磨成匀浆后,转入离心管10 000 r·min−1离心10 min,弃去残渣,上清液即为样品提取液。用Ti2(SO4)-浓氨水法制作过氧化氢标准曲线,取样品提取液1 mL用于反应测定。

-

参考ZOU等[5]的方法,以小鼠细胞色素c单克隆抗体(Merck & Co., Inc)作为一抗(1∶200稀释),用封闭液按1∶50 000稀释相应的HRP标记羊抗小鼠二抗。参照ZOU等[5]的方法,采用高效液相色谱法检测ATP质量分数(ng·g−1)。

-

参考ZOU等[4]的方法测定桂花乙烯释放量(nL·g−1)。

-

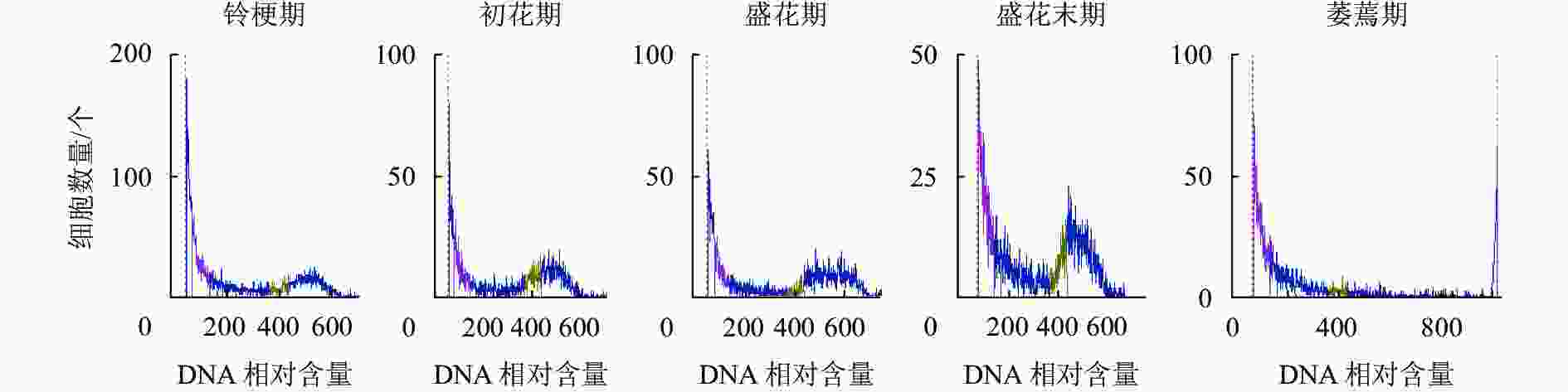

参考YAMADA等[9]的方法,采用流式细胞法测定不同衰老时期桂花花瓣中核含量(DNA团块)的变化。将桂花花瓣置于细胞核提取缓冲液中,将提取物通过50 μm尼龙网过滤,收集分离介质和DNA凝聚物,DAPI染色后,将溶液旋涡混合,用流式细胞仪分析从细胞核中分离出的DNA,计算并分析5 000个样品细胞中所含有核的DNA相对含量。流式细胞仪的仪器型号为BECKMAN COULTER (Cell Lab QuantaTM),仪器条件为:Ev 2.36;FL1 5.12、5.9;SS 5.12;5 000个细胞。

-

每处理3次生物学重复,数据为平均值±标准误。用SAS v.8.0.软件进行方差分析和多重比较分析(Duncan, P=0.05)。

-

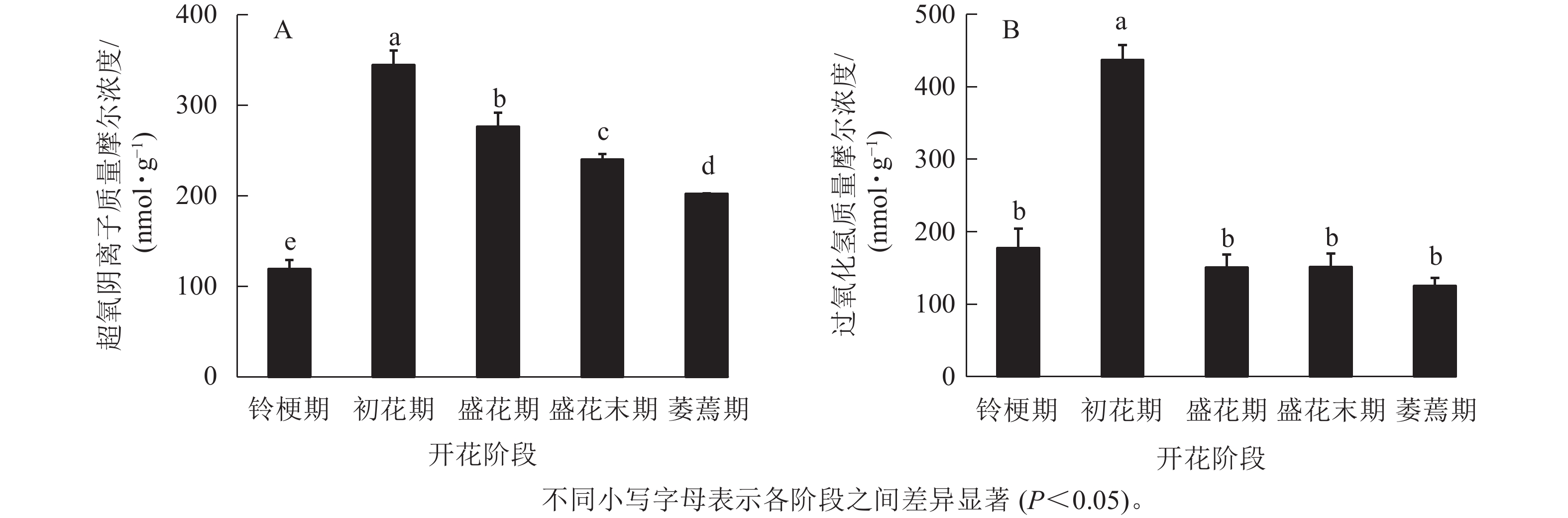

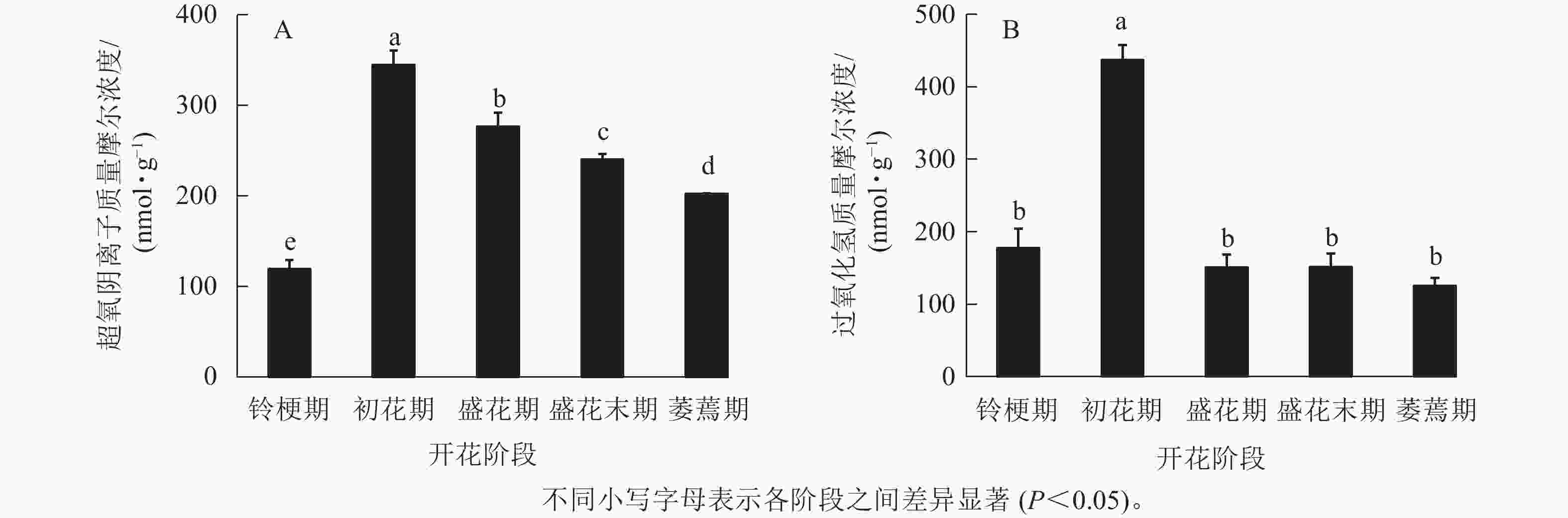

在‘潢川金桂’桂花开花至衰老过程中,超氧阴离子质量摩尔浓度在初花期显著上升到最大值,为344.6 nmol·g−1,其后逐渐降低至200 nmol ·g−1(图1 A)。在‘潢川金桂’初花期花朵刚开放时,过氧化氢的质量摩尔浓度也显著地迅速上升到最大值,为437 nmol·g−1,此时过氧化氢质量摩尔浓度是花苞期的3倍。在随后衰老过程中,过氧化氢又下降到花苞期的水平(图1 B)。

-

如图2所示:从线粒体释放细胞质中的细胞色素c在初花和盛花期变得明显,表明此时已经发生了线粒体细胞色素c的泄漏;在盛花末期开始逐渐减弱,在萎蔫期的花瓣中则逐渐消失,可能与此时花瓣衰老细胞膜功能逐渐丧失有关。

-

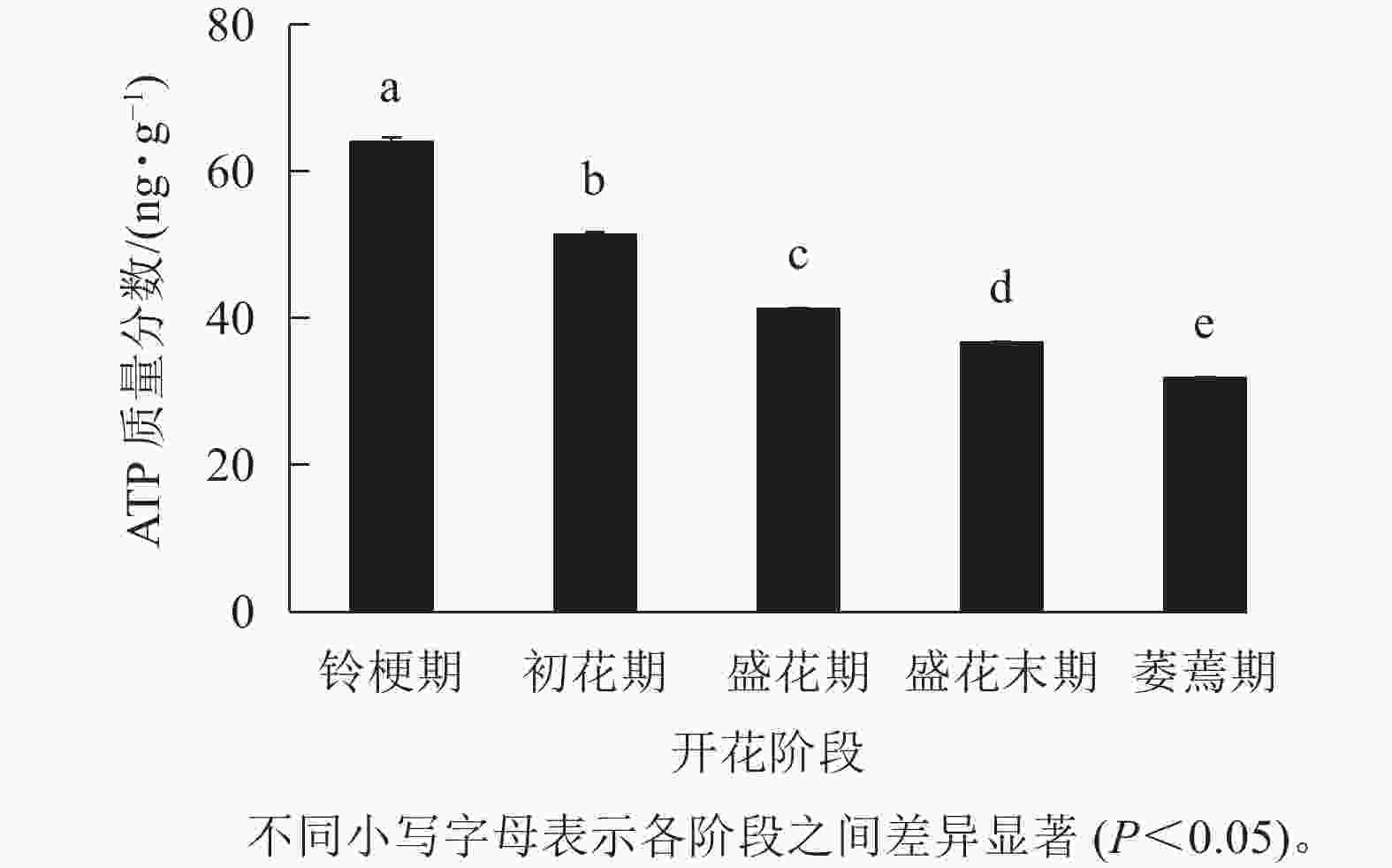

如图3 所示:在‘潢川金桂’的铃梗期花瓣中测量到较高的ATP水平(63.9 ng·g−1),但随着花朵的开放至萎蔫期时,‘潢川金桂’花瓣中的ATP质量分数为31.8 ng·g−1,只有花苞期的一半。由此可见,在桂花花瓣衰老过程中ATP消耗或缺乏可能是PCD发生的早期信号。

-

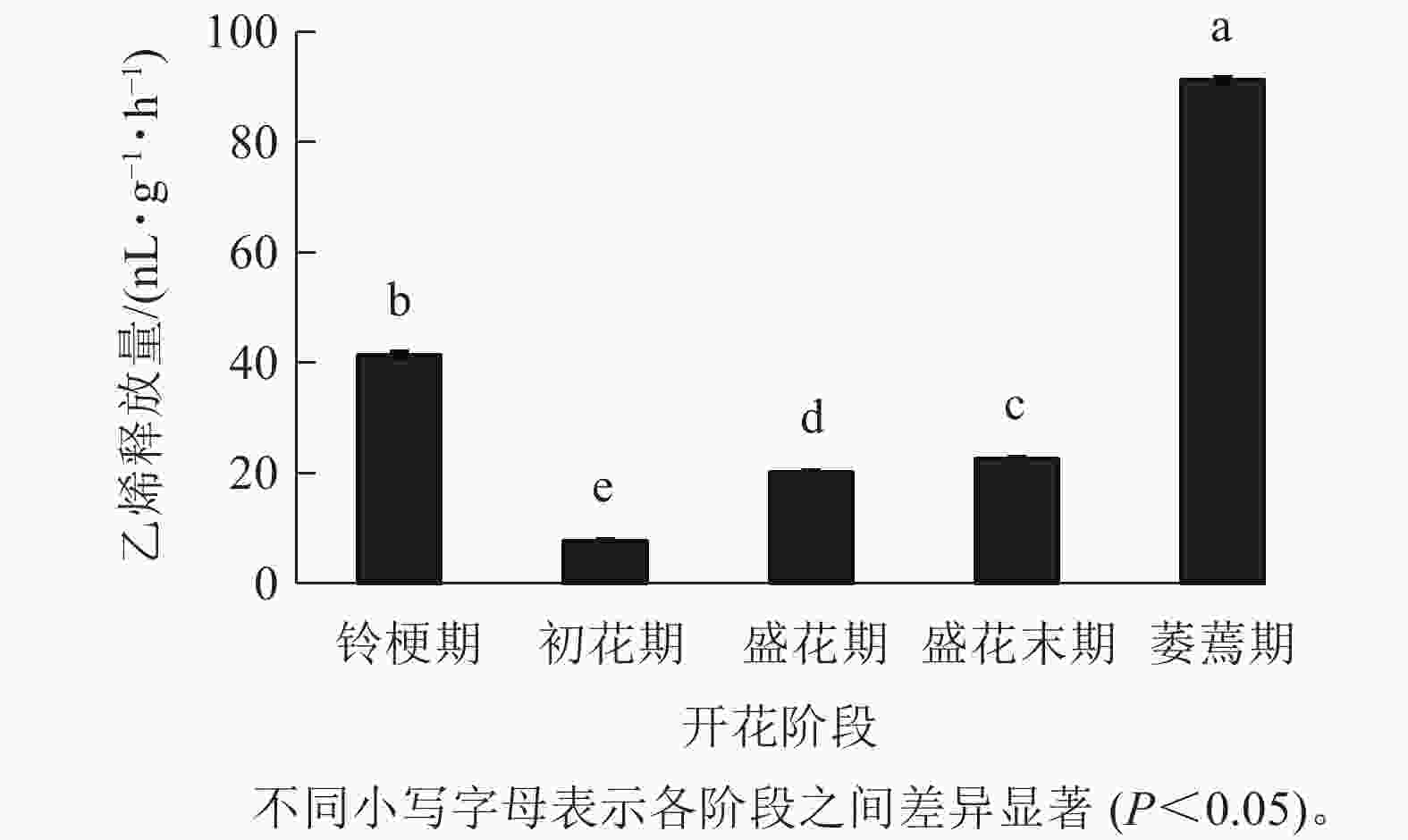

在‘潢川金桂’开放及衰老过程中,乙烯释放量从盛花期开始逐渐上升;盛花末期花瓣出现可见的外观衰老特征时,其释放量显著增加到35.9 nL·g−1·h−1,而在萎蔫期时上升至最大值,为91.2 nL·g−1·h−1(图4),因此乙烯释放类型表现为典型的末期上升型,其释放量的增加可能与花瓣晚期PCD事件的发生相关。

-

如图5所示:DNA相对含量在开花早期相对稳定,而随着花瓣衰老进程的发展,核DNA相对含量逐渐降解,直到萎蔫期花瓣的核DNA基本消失,暗示着核DNA完全降解。

-

花瓣衰老标志着花朵生命的最后阶段,是发育相关的PCD[9]。PCD的诱发和执行过程都常常伴随一系列典型的生理、生化、形态学上的变化以及特征事件[10-11]。在动物细胞PCD进程中,ROS可以作为信号分子激活线粒体上非特异性的通透性孔道(PTP)开放[11-17],从而造成线粒体中细胞色素c和凋亡诱导因子(AIF)释放到细胞质中,而后细胞色素c与凋亡酶激活因子(Apaf-1)结合,从而促使细胞发生PCD[10]。在本研究中,‘潢川金桂’活性氧含量在初花期急剧增加,可能是桂花花瓣PCD早期诱导因子。作为线粒体中电子传递链的重要组成成分,细胞色素c泄露会导致电子传递链受阻,线粒体功能活性下降,从而导致ATP减少[18],最终加快花瓣衰老。在‘潢川金桂’花瓣衰老过程中,细胞质中细胞色素c逐渐积累,至盛花期达到最大,ATP水平从初花期开始持续下降,说明此时线粒体功能活性已逐渐丧失。在郁金香花瓣中,能量损耗也被认为是诱发细胞程序性死亡的早期信号[15]。

有些不结实的桂花栽培品种,盛花后2~3 d,在花瓣仍然具有膨压时便脱落[5-6];而在大多结实的桂花栽培种中,通常以花瓣萎蔫为衰老特征。乙烯是一种促进成熟与衰老的激素,也是导致花瓣发生细胞程序性死亡的因素之一,在促进DNA片段化、导致花瓣脱落和枯萎等方面发挥着作用[12]。研究表明:大多数植物的花瓣脱落都对乙烯敏感,且受到内源乙烯的调控[19-20]。在‘柳叶金桂’衰老过程中,乙烯的增加导致花瓣细胞中液泡结构损坏,在外观上表现为花瓣褐化和失水萎蔫[4]。也有研究发现:花瓣明显可见的萎蔫常常伴随着乙烯峰骤变,该乙烯骤变多又与授粉结实有关[21-23]。在本研究中,当结实型桂花品种‘潢川金桂’萎蔫期花瓣内乙烯释放量增加到最大值时,对应的外观形态上表现出枯萎、褐化,细胞内部发生核DNA的降解等现象,说明乙烯可能是导致结实型桂花花瓣衰老的主要执行因子。在月季Rosa × hybrida花瓣程序性死亡的研究中发现:施用外源乙烯可以诱导ACC基因的表达,促进内源乙烯的生物合成,从而加速PCD进程[24]。

DNA断裂和降解作为PCD发生的标志性特征之一[25],常表现出经典的“DNA ladders”,如唐菖蒲Gladiolus、六出花Alstroemeria和飞燕草Delphinium belladonna[9, 26-27];而有些植物衰老过程中并没有出现“DNA ladders”,如矮牵牛Petunia[28-29]。在‘柳叶金桂’的花瓣衰老过程中也未检测到“DNA ladders”,但通过原位末端标记法(TUNEL)发现:其花瓣在盛花末期开始发生明显的DNA断裂和降解;且其DNA降解受内源乙烯调控[4, 7]。在本研究中,花瓣衰老后期乙烯的骤变与后期DNA相对含量的下降,说明乙烯可能促进了“潢川金桂”花瓣DNA的降解,在矮牵牛[30]和豌豆Pisum sativum[31]中也有类似报道。

-

本研究探索了结实桂花品种‘潢川金桂’衰老的PCD特征,表明ROS激发、细胞色素c释放和ATP质量分数下降是早期PCD诱导因子;乙烯跃变可能作为晚期作用因子促进花瓣细胞的失水、萎蔫和DNA降解。

Programmed cell death events during the petal senescence of Osmanthus fragrans ‘Huangchuan Jingui’

-

摘要:

目的 探索了结实型桂花Osmanthus fragrans花瓣衰老过程中,生理生化变化,为提高桂花园林赏花价值与经济用花价值提供理论依据。 方法 以‘潢川金桂’O. fragrans ‘Huangchuan Jingui’为材料,采用蛋白质印迹法测定细胞质中细胞色素c的释放,高效液相色谱法检测腺嘌呤核苷三磷酸(ATP),气相色谱法测定内源乙烯释放,流式细胞法检测核DNA变化,以及检测桂花开放及衰老过程中超氧自由基等生理指标变化。 结果 ①桂花花瓣中超氧阴离子和过氧化氢质量摩尔浓度在初花期达到最高值,随后逐渐下降。②细胞色素c的含量在初花期开始积累至盛花期最高,在盛花末期开始减少至消失,而ATP质量分数一直呈下降趋势。③乙烯释放量从盛花末期开始逐渐上升至萎蔫期达到最大值,此时花瓣中的核物质也基本消失。④桂花花瓣中活性氧的激发、细胞色素c释放和ATP持续下降明显发生于初花期,为早期细胞程序性死亡(PCD)事件;乙烯跃变、DNA降解发生在盛花末期之后,为晚期PCD事件。 结论 线粒体功能活性下降可能是桂花花瓣早期PCD信号,内源乙烯跃变引起花瓣萎蔫失水和DNA降解可能是PCD执行的结果。图5参31 Abstract:Objective This study, with an investigation of the physiological and biochemical changes during the senescence of sweet Osmanthus fragrans flowers, is aimed to provide guidance for improving both ornamental and economical value of O. fragrans. Method With O. fragrans ‘Huangchuan Jingui’ selected as the experimental material, the release of cytochrome c (Cyt c) in the cytoplasm was determined by Western blotting; the content of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was determined by high performance liquid chromatography; the endogenous ethylene production was determined by gas chromatography; the content of nuclear DNA were detected by flow cytometry and the changes of other physiological indicators such as free radicals during the flowering were also detected. Result (1) The amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in osmanthus petals reached the highest value in the initial flowering stage, and then it gradually decreased; (2) The content of Cyt c began to accumulate in the initial flowering stage and reached the highest in the full flowering stage, but decreased at the late full flowering stage whereas the ATP content declined during the whole flowering stages; (3) The ethylene release gradually increased from late full flowering stage to the maximum in the wilting petals, at which time the nuclear matter in the petals also disappeared; (4) The excitation of ROS, the release of Cyt c into the cytoplasm and the continuous decrease of ATP in petals of O. fragrans ‘Huangchuan Jingui’ mainly occurred in the initial flowering stage, which was an early programmed cell death (PCD) event while the climacteric of ethylene production and DNA degradation occurred in the late flowering stage, referred to as late PCD events. Conclusion Just as the decrease of mitochondrial functional activity may be the early PCD signal during the petal senescence of sweet osmanthus, petal wilting and DNA degradation related to endogenous ethylene production may be the result of PCD execution. [Ch, 5 fig. 31 ref.] -

Key words:

- Osmanthus fragrans /

- programmed cell death /

- petal senescence /

- cytochrome c /

- adenosine triphosphate (ATP) /

- ethylene

-

-

[1] WANG Limei, LI Maoteng, JIN Wenwen, et al. Variations in the components of Osmanthus fragrans Lour. essential oil at different stages of flowering [J]. Food Chemistry, 2009, 114(1): 233 − 236. [2] WU Lichen CHANG Lihui, CHEN Sihan, et al. Antioxidant activity and melanogenesis inhibitory effect of the acetonic extract of Osmanthus fragrans: a potential natural and functional food flavor additive [J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2009, 42(9): 1513 − 1519. [3] CAI Xuan, MAI Rongzhang, ZOU Jingjing, et al. Analysis of aroma-active compounds in three sweet osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans) cultivars by GC-olfactometry and GC-MS [J]. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B (Biomedicine & Biotechnology), 2014, 15(7): 638 − 648. [4] ZOU Jingjing, ZHOU Yuan, CAI Xuan, et al. Increase in DNA fragmentation and the role of ethylene and reactive oxygen species in petal senescence of Osmanthus fragrans [J]. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2014, 93: 97 − 105. [5] ZOU Jingjing, CAI Xuan, WANG Caiyun. The spatial and temporal distribution of programmed cell death (PCD) during petal senescence of Osmanthus fragrans [J]. Acta Horticulturae, 2017, 1185(39): 315 − 324. [6] 向其柏, 刘玉莲. 中国桂花品种图志[M]. 杭州: 浙江科学技术出版社, 2008: 93 − 260. XIANG Qibai, LIU Yulian. An Illustrated Monograph of the Sweet Osmanthus Cultivars in China [M]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Science & Technology Press, 2008: 93 − 260. [7] 周媛. 桂花花瓣衰老过程中细胞程序性死亡特征与机制研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2008. ZHOU Yuan. Research on Characters and Mechanism of Programmed Cell Death (PCD) during the Petal Senescence in Osmanthus fragrans [D]. Wuhan: Huazhong Agricultural University, 2008. [8] 林植芳, 李双顺, 林桂珠, 等. 衰老叶片和叶绿体中H2O2的累积与膜脂过氧化的关系[J]. 植物生理学报, 1988, 14(1): 16 − 22. LIN Zhifang, LI Shuangshun, LIN Guizhu, et al. Relationship between H2O2 accumulation and membrane lipid peroxidation in senescent leaves and chloroplasts [J]. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 1988, 14(1): 16 − 22. [9] YAMADA T, ICHIMURA K, van DOORN W G. Relationship between petal abscission and programmed cell death in Prunus yedoensis and Delphinium belladonna [J]. Planta, 2007, 226(5): 1195 − 1205. [10] 吴兰芳, 杨爱珍, 刘和, 等. 线粒体调控细胞凋亡的研究进展[J]. 中国农学通报, 2010, 26(8): 63 − 68. WU Lanfang, YANG Aizhen, LIU He, et al. The study progress of apoptosis of regulation of mitochondrial [J]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2010, 26(8): 63 − 68. [11] 赵云罡, 徐建兴. 线粒体, 活性氧和细胞凋亡[J]. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2001, 28(2): 168 − 171. ZHAO Yungang, XU Jianxing. Mitochondria, reactive oxygen species and apoptosis [J]. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2001, 28(2): 168 − 171. [12] ZHOU Yuan, WANG Caiyun CHENG Zhengwei. Effects of exogenous ethylene and ethylene inhibitor on longevity and petal senescence of sweet osmanthus [J]. Acta Horticulturae, 2008, 768: 487 − 493. [13] YAMADA T, ICHIMURA K, van DOORN W G. DNA degradation and nuclear degeneration during programmed cell death in petals of Antirrhinum, Argyranthemum, and Petunia [J] Journal of Experimental Botany, 2006, 57(14): 3543 − 3552. [14] van DOORN W G, WOLTERING E J. Physiology and molecular biology of petal senescence [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2008, 59(3): 453 − 480. [15] AZAD A K, ISHIKAWA T, ISHIKAWA T, et al. Intracellular energy depletion triggers programmed cell death during petal senescence in tulip [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2008, 59(8): 2085 − 2095. [16] ROGERS H J. Is there an important role for reactive oxygen species and redox regulation during floral senescence? [J]. Plant Cell Environ, 2012, 35(2): 217 − 233. [17] STEN O, BORIS Z, PIERLUIGI N. Regulation of cell death: the calcium- apoptosis link [J]. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2003, 4(7): 552 − 565. [18] van AKEN O, van BREUSEGEM F. Licensed to kill: mitochondria, chloroplasts, and cell death [J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2015, 20(11): 754 − 766. [19] van DOORN W G. Categories of petal senescence and abscission: a re-evaluation [J]. Annals of Botany, 2001, 87(4): 447 − 456. [20] van DOORN W G. Effect of ethylene on flower abscission: a survey [J]. Annals of Botany, 2002, 89(6): 689 − 693. [21] STEAD A D. Pollination-induced flower senescence: a review [J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 1992, 11(1): 13 − 20. [22] LUANGSUWALAI K, KETSA S, van DOORN W G. Ethylene-regulated hastening of perianth senescence after pollination in Dendrobium flowers is not due to an increase in perianth ethylene production [J]. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2011, 62(3): 338 − 341. [23] SHIMIZU-YUMOTO H, ICHIMURA K. Effects of ethylene, pollination, and ethylene inhibitor treatments on flower senescence of gentians [J]. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2012, 63(1): 111 − 115. [24] 潘海春. 月季花发育过程中花瓣细胞程序化死亡机制研究[D]. 泰安: 山东农业大学, 2004. PAN Haichun. Programmed Cell Death in Petal during Rose (Rosa×hybrida) Flower Development [D]. Tai’an: Shandong Agricultural University, 2004. [25] ALEKSANDRUSHKINA N I, VANYUSHIN B F. Endonucleases and their involvement in plant apoptosis [J]. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology, 2009, 56(3): 291 − 305. [26] WAGSTAFF C, MALCOLM P, RAFIQ A, et al. Programmed cell death (PCD) processes begin extremely early in Alstroemeria petal senescence [J]. New Phytologist, 2003, 160(1): 49 − 59. [27] ARORA A, SINGH V P. Polyols regulate the flower senescence by delaying programmed cell death in Gladiolus [J]. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2006, 15: 139 − 142. [28] YAMADA T, ICHIMURA K, van DOOORN W G. DNA degradation and nuclear degeneration during programmed cell death in petals of Antirrhinum, Argyranthemum, and Petunia [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2006, 57(14): 3543 − 3552. [29] YAMADA T, TAKATSU Y, KASUMI M, et al. Nuclear fragmentation and DNA degradation during programmed cell death in petals of morning glory (Ipomoea nil) [J]. Planta, 2006, 224: 1279 − 1290. [30] LANGSTON B J, BAI S, JONES M L. Increases in DNA fragmentation and induction of a senescence-specific nuclease are delayed during corolla senescence in ethylene-insensitive (etr1-1) transgenic petunias [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2005, 56(409): 15 − 23. [31] ORZAEZ O, GRANELL A. DNA fragmentation is regulated by ethylene during carpel senescence in Pisum sativum [J]. The Plant Journal, 1997, 11(1): 137 − 144. -

-

链接本文:

https://zlxb.zafu.edu.cn/article/doi/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20220782

下载:

下载: