| [1] |

张英杰. 蝴蝶兰花期的分子调控机制研究[D]. 北京: 北京林业大学, 2023. |

ZHANG Yingjie. Molecular Regulation Mechanism of Flowering Time of Phalaenopsis[D]. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University, 2023. |

| [2] |

孙静清. 不同处理措施对菊花生长的影响[J]. 北方园艺, 2008(12): 130−132. |

SUN Jingqing. Effects of different treatment measures on Chrysanthemum growth [J]. Northern Horticulture, 2008(12): 130−132. |

| [3] |

万亚楠. 菊花的花期调控方法初探[J]. 现代园艺, 2013(10): 50−51. |

WAN Ya’nan. Preliminary study on flowering regulation method of Chrysanthemum [J]. Contemporary Horticulture, 2013(10): 50−51. |

| [4] |

CANNON J A, SHEN Li, JHUND P S, et al. Clinical outcomes according to QRS duration and morphology in the irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function (I-PRESERVE) trial [J]. European Journal of Heart Failure, 2016, 18(8): 1021−1031. |

| [5] |

CHAHTANE H, LAI Xuelei, TICHTINSKY G, et al. Flower development in Arabidopsis [J]. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2023, 2686: 3−38. |

| [6] |

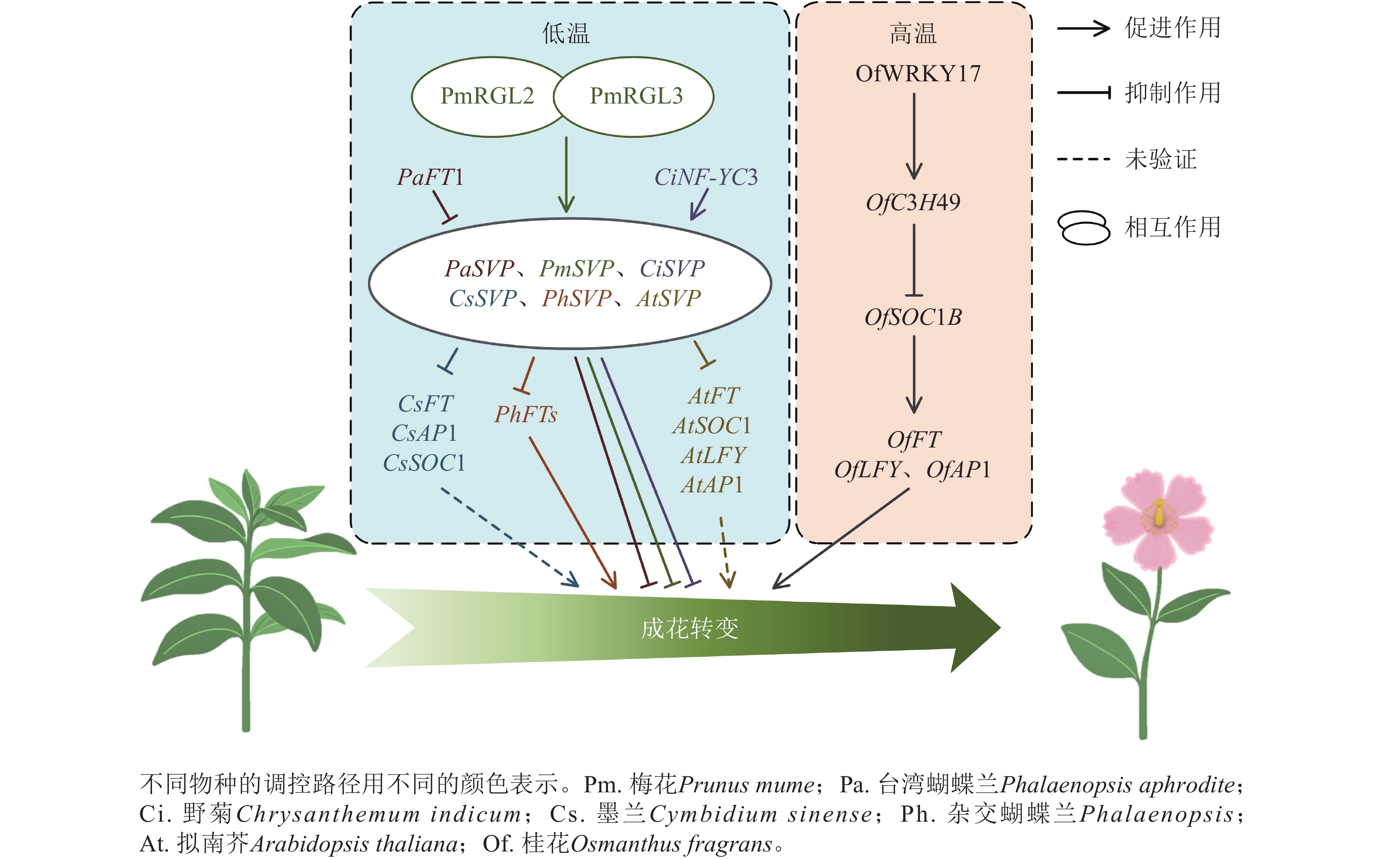

GAO Feng, SEGBO S, HUANG Xiao, et al. PmRGL2/PmFRL3-PmSVP module regulates flowering time in Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc. )[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2025, 48(5): 3415−3430. |

| [7] |

YU Rui, XIONG Zhiying, ZHU Xinhui, et al. RcSPL1–RcTAF15b regulates the flowering time of rose (Rosa chinensis)[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2023, 10(6): uhad083[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1093/hr/uhad083. |

| [8] |

BASTOW R, MYLNE J S, LISTER C, et al. Vernalization requires epigenetic silencing of FLC by histone methylation [J]. Nature, 2004, 427(6970): 164−167. |

| [9] |

FENG Jingqiu, XIA Qian, ZHANG Fengping, et al. Is seasonal flowering time of Paphiopedilum species caused by differences in initial time of floral bud differentiation [J/OL]. AoB Plants, 2021, 13(5): plab053[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1093/aobpla/plab053. |

| [10] |

许申平, 张燕, 袁秀云, 等. 依据显微结构及光合特性探讨蝴蝶兰花芽分化的时期[J]. 园艺学报, 2020, 47(7): 1359−1368. |

XU Shenping, ZHANG Yan, YUAN Xiuyun, et al. Explore the key period of floral determination based on the microstructure and photosynthetic characteristics in Phalaenopsis [J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2020, 47(7): 1359−1368. |

| [11] |

李岩, 刘朝辉, 许会敏. 植物显微技术实验教程[M]. 北京: 中国农业大学出版社, 2022: 104. |

LI Yan, LIU Zhaohui, XU Huimin. Experimentaf Course of Plant Microtechnique[M]. Beijing: China Agricultural University Press, 2022: 104. |

| [12] |

魏钰, 董知洋, 张蕾, 等. 大百合花序分化及生理生化特征[J]. 中国农业大学学报, 2023, 28(8): 108−118. |

WEI Yu, DONG Zhiyang, ZHANG Lei, et al. Inflorescence differentiation of Cardiocrinum giganteum and its morphological and physiological-biochemical characteristics [J]. Journal of China Agricultural University, 2023, 28(8): 108−118. |

| [13] |

孙阳, 朱栗琼, 关超, 等. 木兰科白兰花芽分化的形态学分析[J/OL]. 分子植物育种, 2023-04-23[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20230420005&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

SUN Yang, ZHU Liqiong, GUAN Chao, et al. Morphological observation of flower bud differentiation process of Michelia alba[J/OL]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2023-04-23[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20230420005&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

| [14] |

蔡艳飞, 施自明, 付学维, 等. 山茶花‘烈香’花芽分化进程及内源激素变化[J/OL]. 分子植物育种, 2024-07-22[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20240718002&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

CAI Yanfei, SHI Ziming, FU Xuewei, et al. Flower bud differentiation and endogenous hormone changes of Camellia ‘High Fragrance’[J/OL]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2024-07-22[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20240718002&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

| [15] |

周华近, 张志敏, 王贤荣, 等. 雪落樱花芽形态分化探究[J/OL]. 分子植物育种, 2024-03-07[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20240301004&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

ZHOU Huajin, ZHANG Zhimin, WANG Xianrong, et al. Exploration of the morphological differentiation of Cerasus xueluoensis buds[J/OL]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2024-03-07[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20240301004&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

| [16] |

任莉萍. 基于转录组夏菊花芽分化和菊花脑低温响应的优异基因挖掘[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2015. |

REN Liping. Excellent Gene Mining Related to Flower Bud Differentiation in Summmer Flowering Chrysanthemum and Response to Low Temperature in Chrysanthemum nankingense[D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2015. |

| [17] |

胡晓龙, 田绍泽, 胡惠蓉. ‘晨光’大花金鸡菊花芽分化及光周期特性研究[J]. 南京林业大学学报(自然科学版), 2019, 43(4): 43−47. |

HU Xiaolong, TIAN Shaoze, HU Huirong. Study on floral bud differentiation and photoperiod characteristics of Coreopsis grandiflora ‘Early Sunrise’ [J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Sciences Edition), 2019, 43(4): 43−47. |

| [18] |

石万里, 姚毓璆. 菊花花芽分化初步研究[J]. 园艺学报, 1990, 17(4): 309−312, 324. |

SHI Wanli, YAO Yuqiu. Preliminary researches on flower bud differentiation of Chrysanthemums [J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 1990, 17(4): 309−312, 324. |

| [19] |

YIN Yuying, LI Ji, GUO Beiyi, et al. Exogenous GA3 promotes flowering in Paphiopedilum callosum (Orchidaceae) through bolting and lateral flower development regulation[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2022, 9: uhac091p[2025-08-29]. DOI: 10.1093/hr/uhac091. |

| [20] |

李元鹏, 张英杰, 张京伟, 等. 月季花芽分化形态观测及遮阴对其进程的影响[J]. 分子植物育种, 2024, 22(8): 2715−2721. |

LI Yuanpeng, ZHANG Yingjie, ZHANG Jingwei, et al. Observation on morphology of flower bud differentiation and the effect of shading on the process of Rosa [J]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2024, 22(8): 2715−2721. |

| [21] |

胡鑫, 王彦杰, 金奇江, 等. 活体取样并鉴定荷花花芽分化时期的方法研究[J]. 江苏农业科学, 2018, 46(24): 113−115. |

HU Xin, WANG Yanjie, JIN Qijiang, et al. Study on methods of sampling in vivo and flower bud differentiation period identification of Nelumbo nucifera [J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2018, 46(24): 113−115. |

| [22] |

张亚梅, 曹云冰, 张一单. 4个郁金香品种在博州温室的引种试验[J]. 南方农业, 2025, 19(14): 14−16. |

ZHANG Yamei, CAO Yunbing, ZHANG Yidan. Introduction experiment of four tulip varieties in greenhouse in Bozhou [J]. South China Agriculture, 2025, 19(14): 14−16. |

| [23] |

王英, 张超, 付建新, 等. 桂花花芽分化和花开放研究进展[J]. 浙江农林大学学报, 2016, 33(2): 340−347. |

WANG Ying, ZHANG Chao, FU Jianxin, et al. Progresses on flower bud differentiation and flower opening in Osmanthus fragrans [J]. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University, 2016, 33(2): 340−347. |

| [24] |

陈庭巧, 董晓晓, 袁涛, 等. 单花、有侧花牡丹品种花芽分化特点及内源激素变化[J]. 广西植物, 2023, 43(2): 368−378. |

CHEN Tingqiao, DONG Xiaoxiao, YUAN Tao, et al. Flower bud differentiation characteristics and endogenous hormone changes of in single and lateral-flowered tree peony (Paeonia Sect. Moutan) cultivars [J]. Guihaia, 2023, 43(2): 368−378. |

| [25] |

王桐霖, 吕梦雯, 徐金光, 等. 芍药鳞芽年发育进程及生理机制的研究[J]. 植物生理学报, 2019, 55(8): 1178−1190. |

WANG Tonglin, LÜ Mengwen, XU Jinguang, et al. Study on the developmental process and physiological mechanism of the bulbils of Paeonia lactiflora [J]. Plant Physiology Journal, 2019, 55(8): 1178−1190. |

| [26] |

张继娜. 郁金香花芽分化的观察与研究[J]. 甘肃农业大学学报, 2006, 41(4): 41−44. |

ZHANG Jina. Observation and research on flower bud differentiation of tulip in Lanzhou [J]. Journal of Gansu Agricultural University, 2006, 41(4): 41−44. |

| [27] |

龚湉. 寒兰成花机理及花期调控研究[D]. 福州: 福建农林大学, 2015. |

GONG Tian. Mechanism of Floral Formation of Cymbidium kanran and Flowering Regulation[D]. Fuzhou: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, 2015. |

| [28] |

李淑娴. 墨兰成花机理及花期调控技术研究[D]. 福州: 福建农林大学, 2016. |

LI Shuxian. Mechanism of Flower Development and Early Flowering Technique of Cymbidium sinense[D]. Fuzhou: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, 2016. |

| [29] |

刘晓芬, 凌晓祺, 向理理, 等. 温度和赤霉素对春兰开花的调控[J]. 浙江农业学报, 2023, 35(2): 355−363. |

LIU Xiaofen, LING Xiaoqi, XIANG Lili, et al. Effect of temperature and gibberellin on flowering regulation of Cymbidium goeringii [J]. Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis, 2023, 35(2): 355−363. |

| [30] |

张国兵, 罗玉兰. 八仙花花芽分化形态观察及成花机理研究[J]. 中国农学通报, 2019, 35(34): 72−76. |

ZHANG Guobing, LUO Yulan. Architectural development of inflorescence and flowering mechanism of Hydrangea macrophyflla [J]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2019, 35(34): 72−76. |

| [31] |

范李节, 陈梦倩, 王宁杭, 等. 3种木兰属植物花芽分化时期及形态变化[J]. 东北林业大学学报, 2018, 46(1): 27−30, 39. |

FAN Lijie, CHEN Mengqian, WANG Ninghang, et al. Flower bud differentiation of three species of Magnolia [J]. Journal of Northeast Forestry University, 2018, 46(1): 27−30, 39. |

| [32] |

陈香波, 张冬梅, 傅仁杰, 等. 白玉兰二次开花诱导与生理调控研究[J]. 南京林业大学学报(自然科学版), 2024, 48(5): 97−104. |

CHEN Xiangbo, ZHANG Dongmei, FU Renjie, et al. Induction and physiological regulatory mechanism of secondary flowering in Yulannia denudata [J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Sciences Edition), 2024, 48(5): 97−104. |

| [33] |

罗培润. 生长调节剂诱导杜鹃花芽形成及打破休眠提早开花效应[D]. 福州: 福建农林大学, 2023. |

LUO Peirun. Effects of Growth Regulators on Bud Formation and Early Flowering of Rhododendron [D]. Fuzhou: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, 2023. |

| [34] |

SHEPPARD T L. Flowers from a sweetheart[J/OL]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2013, 9(4): 215[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.1222. |

| [35] |

AMASINO R. Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering [J]. The Plant Journal, 2010, 61(6): 1001−1013. |

| [36] |

CORBESIER L, VINCENT C, JANG S, et al. FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis [J]. Science, 2007, 316(5827): 1030−1033. |

| [37] |

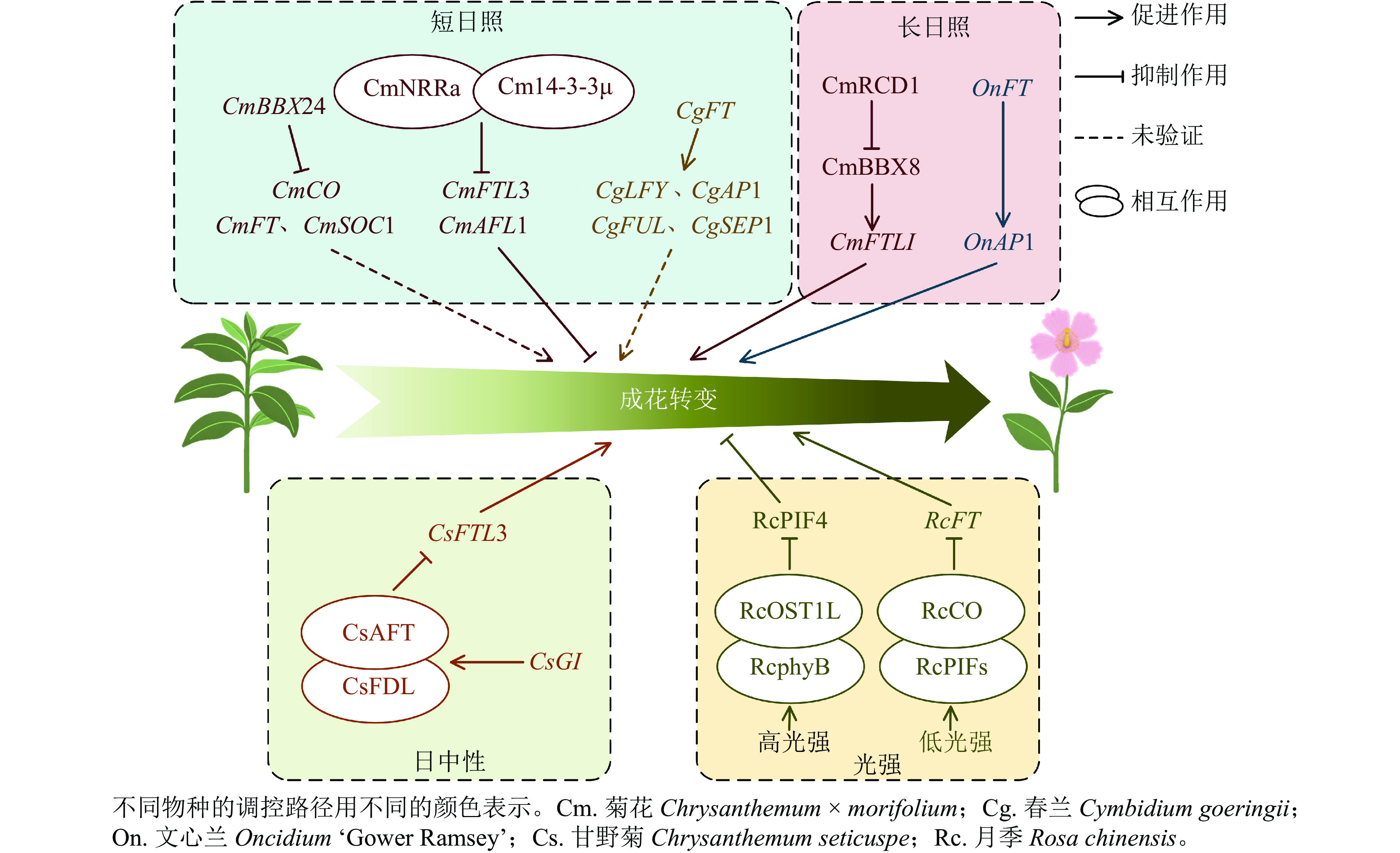

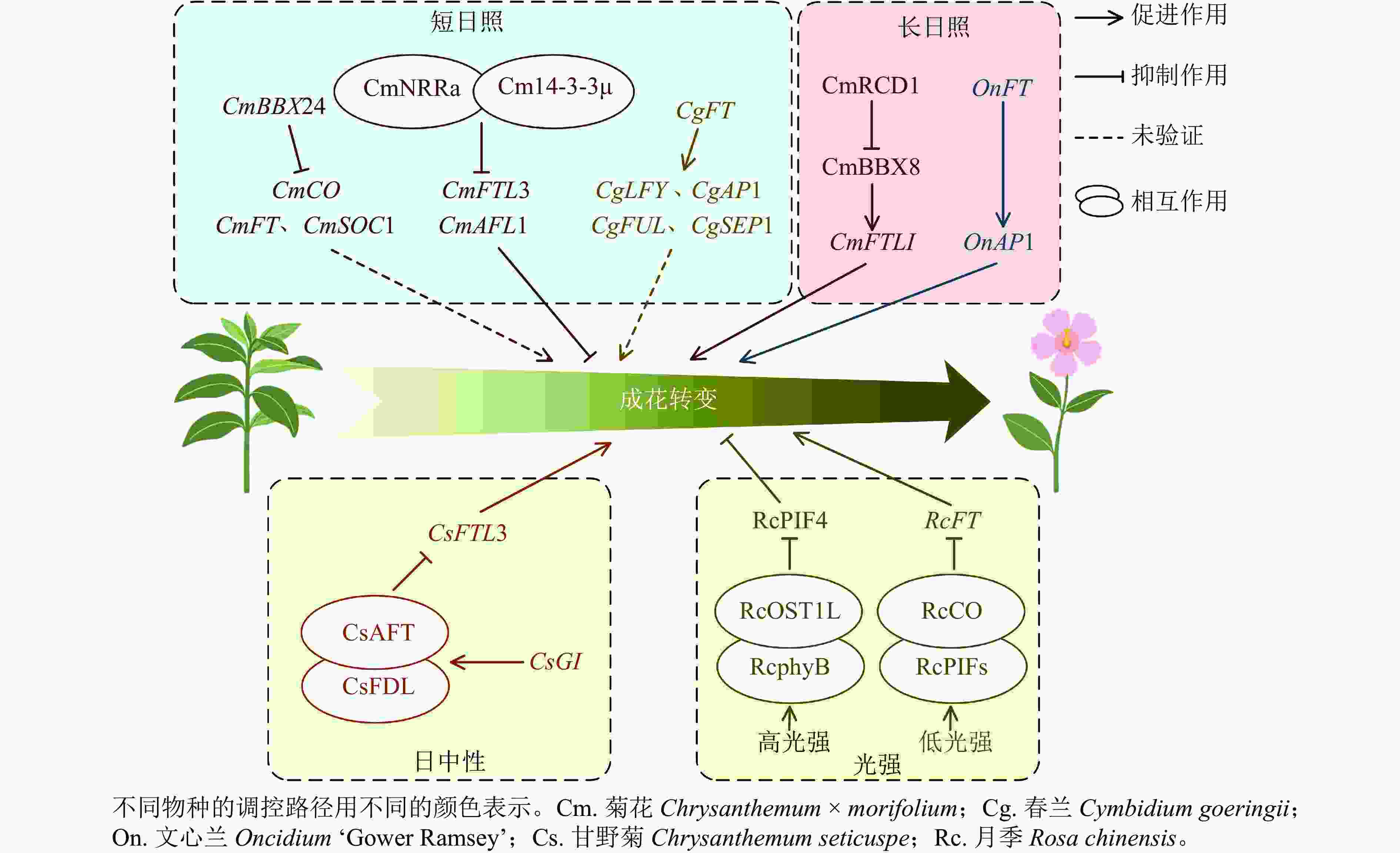

WANG Lijun,CHENG Hua, WANG Qi, et al. CmRCD1 represses flowering by directly interacting with CmBBX8 in summer chrysanthemum [J]. Horticulture Research, 2021, 8(1): 79−79. |

| [38] |

CHENG Hua, ZHANG Jiaxin, ZHANG Yu, et al. The Cm14-3-3μ protein and CCT transcription factor CmNRRa delay flowering in Chrysanthemum [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2023, 74(14): 4063−4076. |

| [39] |

MAO Yachao, SUN Jing, CAO Peipei, et al. Functional analysis of alternative splicing of the FLOWERING LOCUS T orthologous gene in Chrysanthemum morifolium[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2016, 3: 16058[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1038/hortres.2016.58. |

| [40] |

HIGUCHI Y, NARUMI T, ODA A, et al. The gated induction system of a systemic floral inhibitor, antiflorigen, determines obligate short-day flowering in chrysanthemums [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(42): 17137−17142. |

| [41] |

ODA A, HIGUCHI Y, HISAMATSU T. Constitutive expression of CsGI alters critical night length for flowering by changing the photo-sensitive phase of anti-florigen induction in chrysanthemum[J/OL]. Plant Science, 2020, 293: 110417[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110417. |

| [42] |

ODA A, NARUMI T, LI Tuoping, et al. CsFTL3, a Chrysanthemum FLOWERING LOCUS T-like gene, is a key regulator of photoperiodic flowering in chrysanthemums [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2012, 63(3): 1461−1477. |

| [43] |

NAKANO Y, TAKASE T, TAKAHASHI S, et al. Chrysanthemum requires short-day repeats for anthesis: gradual CsFTL3 induction through a feedback loop under short-day conditions[J]. Plant Science, 2019, 283: 247−255. |

| [44] |

YANG Yingjie, MA Chao, XU Yanjie, et al. A zinc finger protein regulates flowering time and abiotic stress tolerance in chrysanthemum by modulating gibberellin biosynthesis [J]. The Plant Cell, 2014, 26(5): 2038−2054. |

| [45] |

张子昕. 菊花CmTPL1-2调控开花的分子机制研究[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2019. |

ZHANG Zixin. The Molecular Mechanism of Chrysanthemum CmTPL1-2 Involved in the Flowering Regulation [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2019. |

| [46] |

HOU Chengjing, YANG C H. Functional analysis of FT and TFL1 orthologs from orchid (Oncidium ‘Gower Ramsey’) that regulate the vegetative to reproductive transition [J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2009, 50(8): 1544−1557. |

| [47] |

HUANG Weiting, FANG Zhongming, ZENG Songjun, et al. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of three FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) homologous genes from Chinese Cymbidium [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2012, 13(9): 11385−11398. |

| [48] |

XIANG Lin, LI Xiaobai, QIN Dehui, et al. Functional analysis of FLOWERING LOCUS T orthologs from spring orchid (Cymbidium goeringii Rchb. f. ) that regulates the vegetative to reproductive transition [J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 2012, 58: 98−105. |

| [49] |

SUN Jingjing, LU Jun, BAI Mengjuan, et al. Phytochrome-interacting factors interact with transcription factor CONSTANS to suppress flowering in rose [J]. Plant Physiology, 2021, 186(2): 1186−1201. |

| [50] |

SUN Jingjing, LIU Hongchi, WANG Weinan, et al. RcOST1L phosphorylates RcPIF4 for proteasomal degradation to promote flowering in rose [J]. New Phytologist, 2024, 243(4): 1387−1405. |

| [51] |

郑慧俊, 龚仲幸, 蔡芳芳, 等. RAV转录因子在植物开花调控中的功能[J/OL]. 分子植物育种, 2023-05-16[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20230515004&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

ZHENG Huijun, GONG Zhongxing, CAI Fangfang, et al. The role of RAV transcription factors in molecular regulation of plant flowering[J/OL]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2023-05-16[2025-08-25]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx filename=FZZW20230515004&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ. |

| [52] |

RANDOUX M, JEAUFFRE J, THOUROUDE T, et al. Gibberellins regulate the transcription of the continuous flowering regulator, RoKSN, a rose TFL1 homologue [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2012, 63(18): 6543−6554. |

| [53] |

RANDOUX M, DAVIÈRE J M, JEAUFFRE J, et al. RoKSN, a floral repressor, forms protein complexes with RoFD and RoFT to regulate vegetative and reproductive development in rose [J]. New Phytologist, 2014, 202(1): 161−173. |

| [54] |

孙晶晶. RcPIFs在遮荫条件下调控月季开花的分子机制[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2021. |

SUN Jingjing. The Molecular Mechanism of Flowering Time Regulation by RcPIFs Under Shade in Rosa chinensis [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2021. |

| [55] |

ZHU Lu, GUAN Yunxiao, LIU Yanan, et al. Regulation of flowering time in chrysanthemum by the R2R3 MYB transcription factor CmMYB2 is associated with changes in gibberellin metabolism[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2020, 7(1): 96[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1038/s41438-020-0317-1. |

| [56] |

LEE J H, YOO S J, PARK S H, et al. Role of SVP in the control of flowering time by ambient temperature in Arabidopsis [J]. Genes & Development, 2007, 21(4): 397−402. |

| [57] |

JANG S, TORTI S, COUPLAND G. Genetic and spatial interactions between FT, TSF and SVP during the early stages of floral induction in Arabidopsis [J]. The Plant Journal, 2009, 60(4): 614−625. |

| [58] |

JANG S, CHOI S C, LI H Y, et al. Functional characterization of Phalaenopsis aphrodite flowering genes PaFT1 and PaFD[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0134987[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134987. |

| [59] |

JIANG Li, JIANG Xiaoxiao, LI Yanna, et al. FT-like paralogs are repressed by an SVP protein during the floral transition in Phalaenopsis orchid [J]. Plant Cell Reports, 2022, 41(1): 233−248. |

| [60] |

YANG Fengxi, GAO Jie, WEI Yonglu, et al. The genome of Cymbidium sinense revealed the evolution of orchid traits [J]. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 2021, 19(12): 2501−2516. |

| [61] |

籍凤娇, 马燕, 亓帅, 等. 芍药PlSVP基因的克隆及其花期调控功能分析[J]. 园艺学报, 2022, 49(11): 2367−2376. |

JI Fengjiao, MA Yan, QI Shuai, et al. Cloning and functional analysis of peony PlSVP gene in regulating flowering [J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2022, 49(11): 2367−2376. |

| [62] |

高耀辉, 魏光普, 马斌, 等. 菊花CmSVP基因结构及表达模式分析[J]. 河南农业科学, 2021, 50(2): 124−129. |

GAO Yaohui, WEI Guangpu, MA Bin, et al. Analysis of CmSVP gene structure and expression pattern in chrysanthemum [J]. Journal of Henan Agricultural Sciences, 2021, 50(2): 124−129. |

| [63] |

ZHANG Zixin, HU Qian, GAO Zheng, et al. Flowering repressor CmSVP recruits the TOPLESS corepressor to control flowering in chrysanthemum [J]. Plant Physiology, 2023, 193(4): 2413−2429. |

| [64] |

WANG Xueting, YAO Yao, WEN Shiyun, et al. Genome-wide characterization of Chrysanthemum indicum nuclear factor Y, subunit C gene family reveals the roles of CiNF-YCs in flowering regulation[J/OL]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022, 23(21): 12812[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3390/ijms232112812. |

| [65] |

YE Yong, LU Xinke, KONG En, et al. OfWRKY17-OfC3H49 module responding to high ambient temperature delays flowering via inhibiting OfSOC1B expression in Osmanthus fragrans[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2025, 12(1): uhae273[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1093/hr/uhae273. |

| [66] |

TASAKI K, HIGUCHI A, FUJITA K, et al. Development of molecular markers for breeding of double flowers in Japanese gentian[J/OL]. Molecular Breeding, 2017, 37(3): 33[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1007/s11032-017-0633-9. |

| [67] |

CHOI K, KIM J, HWANG H J, et al. The FRIGIDA complex activates transcription of FLC, a strong flowering repressor in Arabidopsis, by recruiting chromatin modification factors [J]. The Plant Cell, 2011, 23(1): 289−303. |

| [68] |

HU Qian, YIN Mengru, GAO Zheng, et al. Late flowering in chrysanthemum induced by low ambient temperature is mediated by FLOWERING LOCUS C-like [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2025, 76(8): 2192−2206. |

| [69] |

展妍丽, 王萃铂, 亓钰莹, 等. 菊花开花抑制基因CmFLC-like1的克隆及表达特性分析[J]. 园艺学报, 2015, 42(7): 1347−1355. |

ZHAN Yanli, WANG Cuibo, QI Yuying, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of flowering inhibitor CmFLC-like1 gene in chrysanthemum [J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2015, 42(7): 1347−1355. |

| [70] |

周敏, 程华, 张子昕, 等. 菊花CmETR2基因的克隆及功能分析[J]. 南京农业大学学报, 2020, 43(3): 431−437. |

ZHOU Min, CHENG Hua, ZHANG Zixin, et al. Cloning and functional analysis of CmETR2 gene in chrysanthemum [J]. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University, 2020, 43(3): 431−437. |

| [71] |

LIU Xiaoru, PAN Ting, LIANG Weiqi, et al. Overexpression of an orchid (Dendrobium nobile) SOC1/TM3-like ortholog, DnAGL19, in Arabidopsis regulates HOS1-FT expression[J/OL]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 99[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00099. |

| [72] |

杨秀莲, 贾瑞瑞, 施婷婷, 等. 观赏植物花期调控分子生物学研究进展[J]. 安徽农业大学学报, 2021, 48(3): 344−351. |

YANG Xiulian, JIA Ruirui, SHI Tingting, et al. Advances on molecular biology research of flowering regulation in ornamental plants [J]. Journal of Anhui Agricultural University, 2021, 48(3): 344−351. |

| [73] |

LI Dan, LIU Chang, SHEN Lisha, et al. A repressor complex governs the integration of flowering signals in Arabidopsis [J]. Developmental Cell, 2008, 15(1): 110−120. |

| [74] |

GUAN Yunxiao, DING Lian, JIANG Jiafu, et al. Overexpression of the CmJAZ1-like gene delays flowering in Chrysanthemum morifolium[J/OL]. Horticulture Research, 2021, 8(1): 87[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1038/s41438-021-00525-y. |

| [75] |

HUANG Yaoyao, XING Xiaojuan, TANG Yun, et al. An ethylene-responsive transcription factor and a flowering locus KH domain homologue jointly modulate photoperiodic flowering in Chrysanthemum[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2022, 45(5): 1442−1456. |

| [76] |

WANG Jiawei. Regulation of flowering time by the miR156-mediated age pathway [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2014, 65(17): 4723−4730. |

| [77] |

HYUN Y, RICHTER R, VINCENT C, et al. Multi-layered regulation of SPL15 and cooperation with SOC1 integrate endogenous flowering pathways at the Arabidopsis shoot meristem [J]. Developmental Cell, 2016, 37(3): 254−266. |

| [78] |

LI Xiaoyan, GUO Fu, MA Shengyun, et al. Regulation of flowering time via miR172-mediated APETALA2-like expression in ornamental Gloxinia (Sinningia speciosa) [J]. Journal of Zhejiang University: Science B, 2019, 20(4): 322−331. |

| [79] |

HUANG Ziwei, LIU Guoqin, CHEN Rui, et al. The RhSPL4-RhPRR5L module positively regulates flowering time in rose (Rosa hybrida) [J]. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2025, 11(5): 1930−1942. |

| [80] |

YAMAGISHI M, NOMIZU T, NAKATSUKA T. Overexpression of lily microRNA156-resistant SPL13A stimulates stem elongation and flowering in Lilium formosanum under non-inductive (non-chilling) conditions[J/OL]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2024, 15: 1456183[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1456183. |

| [81] |

WEI Qian, MA Chao, XU Yanjie, et al. Control of Chrysanthemum flowering through integration with an aging pathway[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 829[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-00812-0. |

| [82] |

GAO Xuekai, LIU Lei, WANG Tianle, et al. Aging-dependent temporal regulation of MIR156 epigenetic silencing by CiLDL1 and CiNF-YB8 in chrysanthemum [J]. New Phytologist, 2025, 245(5): 2309−2321. |

| [83] |

YONG Xue, ZHENG Tangchu, HAN Yu, et al. The miR156-targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN (PmSBP) transcription factor regulates the flowering time by binding to the promoter of SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CO1 (PmSOC1) in Prunus mume [J/OL]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022, 23(19): 11976[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3390/ijms231911976. |

| [84] |

JIN S, AHN J H. Regulation of flowering time by ambient temperature: repressing the repressors and activating the activators [J]. New Phytologist, 2021, 230(3): 938−942. |

| [85] |

YANG Mingkang, LIN Wenjie, XU Yarou, et al. Flowering-time regulation by the circadian clock: from Arabidopsis to crops [J]. The Crop Journal, 2024, 12(1): 17−27. |

| [86] |

尹玉莹, 房林, 李琳, 等. 兜兰属植物花期调控研究进展[J]. 热带作物学报, 2022, 43(4): 769−778. |

YIN Yuying, FANG Lin, LI Lin, et al. Advances in flowering regulation of Paphiopedilum [J]. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops, 2022, 43(4): 769−778. |

| [87] |

YUAN Yixin, WANG Zhiling, DONG Rui, et al. LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL is a core component of far-red light-induced flowering in chrysanthemum[J/OL]. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2025[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1016/j.hpj.2025.04.010. |

| [88] |

张艺腾, 龙硕, 吴薇, 等. 光照、水分和肥料对卡特树兰开花特性的影响[J]. 现代园艺, 2023(15): 1−4, 8. |

ZHANG Yiteng, LONG Shuo, WU Wei, et al. Effects of light, water and fertilizer on flowering characteristics of Katsura [J]. Contemporary Horticulture, 2023(15): 1−4, 8. |

| [89] |

BEOM L, JUN J, HYUN L, et al. Correlation between carbohydrate contents in the leaves and inflorescence initiation in Phalaenopsis[J/OL]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2020, 265: 109270[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109270. |

| [90] |

YANG Fengxi, ZHU Genfa, WEI Yonglu, et al. Low-temperature-induced changes in the transcriptome reveal a major role of CgSVP genes in regulating flowering of Cymbidium goeringii[J/OL]. BMC Genomics, 2019, 20(1): 53[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.1186/s12864-019-5425-7. |

| [91] |

LAZARE S, BURGOS A, BROTMAN Y, et al. The metabolic (under)groundwork of the lily bulb toward sprouting [J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2018, 163(4): 436−449. |

| [92] |

蒋心笛, 赵冰. 低温及赤霉素对八仙花盆花花期调控技术的影响[J]. 北方园艺, 2024(1): 67−75. |

JIANG Xindi, ZHAO Bing. Effects of low temperature and combined gibberellin on the regulation techniques of flowering stage of potted Hydrangea [J]. Northern Horticulture, 2024(1): 67−75. |

| [93] |

LEEGGANGERS H A C F, NIJVEEN H, BIGAS J N, et al. Molecular regulation of temperature-dependent floral induction in Tulipa gesneriana [J]. Plant Physiology, 2017, 173(3): 1904−1919. |

| [94] |

LI Xiaofang, JIA Linyan, XU Jing, et al. FT-like NFT1 gene may play a role in flower transition induced by heat accumulation in Narcissus tazetta var. chinensis [J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2013, 54(2): 270−281. |

| [95] |

翁青史. 寒兰(Gymbidium kanran)花期调控技术及花期生理响应研究[D]. 福州: 福建农林大学, 2019. |

WENG Qingshi. Study on the Regulation of Florescence and Physiological Responses During Flowering of Cymbidium kanran [D]. Fuzhou: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, 2019. |

| [96] |

张英杰, 李奥, 吕云飞, 等. 蝴蝶兰成花过程内源激素含量的变化和植物生长调节剂的作用[J]. 热带亚热带植物学报, 2022, 30(1): 104−110. |

ZHANG Yingjie, LI Ao, LÜ Yunfei, et al. Changes in endogenous hormones content and effect of plant growth regulators of Phalaenopsis during flowering period [J]. Journal of Tropical and Subtropical Botany, 2022, 30(1): 104−110. |

| [97] |

李晓莎, 陈涛, 任昂彦, 等. 赤霉素对不同品种观赏向日葵开花特性及形态特征的影响[J]. 江苏农业科学, 2024, 52(3): 184−192. |

LI Xiaosha, CHEN Tao, REN Angyan, et al. Impacts of gibberellin on flowering and morphological characteristics of different ornamental sunflower varieties [J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2024, 52(3): 184−192. |

| [98] |

DONG Bin, DENG Ye, WANG Haibin, et al. Gibberellic acid signaling is required to induce flowering of chrysanthemums grown under both short and long days[J/OL]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2017, 18(6): 1259[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18061259. |

| [99] |

ŽÁRSKÝ V, PAVLOVÁ L, EDER J, et al. Higher flower bud formation in haploid tobacco is connected with higher peroxidase/IAA-oxidase activity, lower IAA content and ethylene production [J]. Biologia Plantarum, 1990, 32(4): 288−293. |

| [100] |

WANG Shanli, VISWANATH K K, TONG C G, et al. Floral induction and flower development of orchids[J/OL]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2019, 10: 1258[2025-08-25]. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01258. |

| [101] |

李奥, 张英杰, 孙纪霞, 等. 植物生长调节剂和温度对蝴蝶兰双梗率、花期及花朵性状的影响[J]. 热带作物学报, 2021, 42(3): 732−738. |

LI Ao, ZHANG Yingjie, SUN Jixia, et al. Effects of plant growth regulators and temperature on the rate of double peduncle, flowering period and flower characteristics of Phalaenopsis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops, 2021, 42(3): 732−738. |

| [102] |

梁文超, 步行, 罗思谦, 等. 氮磷钾复合肥对增温促花后‘长寿冠’海棠生理特性的影响[J]. 南京林业大学学报(自然科学版), 2022, 46(5): 81−88. |

LIANG Wenchao, BU Xing, LUO Siqian, et al. Effects of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium compound fertilization on the physiological characteristics of Chaenomeles speciosa ‘Changshouguan’ after processing of warming in the post floral stage [J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Sciences Edition), 2022, 46(5): 81−88. |

| [103] |

黄永艺, 唐敏, 叶广, 等. 花期调控技术在莲瓣兰产业化中的应用[J]. 北方园艺, 2015(8): 186−190. |

HUANG Yongyi, TANG Min, YE Guang, et al. Application of flowering regulation technology in Cymbidium tortisepalum Fukuyama industrialization [J]. Northern Horticulture, 2015(8): 186−190. |

| [104] |

耿晓东, 周英, 徐铮. 树状月季在苏州地区引种及栽培研究[J]. 现代园艺, 2020(5): 64, 66. |

GENG Xiaodong, ZHOU Ying, XU Zheng. Study on introduction and cultivation of dendritic rose in Suzhou[J]. Contemporary Horticulture, 2020(5): 64, 66. |

| [105] |

裴庆. 菊花种苗繁育及摘心与定植期的研究[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2018. |

PEI Qing. The Study on Chrysanthemum Seedling and Its Pinching and Planting Period [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2018. |

DownLoad:

DownLoad: